19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson writes on the damage done when her cover was blown, journalist John Lloyd looks at how terrorist attacks have affected surveillance needs worldwide, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad explains why he was forced into exile after violent attacks on secular writers, philosopher Julian Baggini looks at the power of literary aliases through the ages, Edward Lucas shares The Economist’s perspective on keeping its writers unnamed, John Crace imagines a meeting at Trolls Anonymous, and Caroline Lees looks at how local journalists, or fixers, can be endangered, or even killed, when they are revealed to be working with foreign news companies. There are are also features on how Turkish artists moonlight under pseudonyms to stay safe, how Chinese artists are being forced to exhibit their works in secret, and an interview with Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot.

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, about the importance of committing to your words, whether you’re a student, an author, or a politician campaigner in the Brexit referendum. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism, in the decade after the murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov looks at how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. Plus there is poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

There is art work from Molly Crabapple, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings, Rebel Pepper, Eva Bee, Brian John Spencer and Sam Darlow.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Does anonymity need to be defended?

Anonymity: worth defending, by Rachael Jolley: False names can be used by the unscrupulous but the right to anonymity needs to be defended

Under the wires, by Caroline Lees : A look at local “fixers”, who help foreign correspondents on the ground, can face death threats and accusations of being spies after working for international media

Art attack, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Ai Weiwei and other artists have increased the popularity of Chinese art, but censorship has followed

Naming names, by Suhrith Parthasarathy: India has promised to crack down on online trolls, but the right to anonymity is also threatened

Secrets and spies, by Valerie Plame Wilson: The former CIA officer on why intelligence agents need to operate undercover, and on the damage done when her cover was blown in a Bush administration scandal

Undercover artist, by Jan Fox: Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot explains why his down-and-out murals never carry his real name

A meeting at Trolls Anonymous, by John Crace: A humorous sketch imagining what would happen if vicious online commentators met face to face

Whose name is on the frame? By Kaya Genç: Why artists in Turkey have adopted alter egos to hide their more political and provocative works

Spooks and sceptics, by John Lloyd: After a series of worldwide terrorist attacks, the public must decide what surveillance it is willing to accept

Privacy and encryption, by Bethany Horne: An interview with human rights researcher Jennifer Schulte on how she protects herself in the field

“I have a name”, by Ananya Azad: A Bangladeshi blogger speaks out on why he made his identity known and how this put his life in danger

The smear factor, by Rupert Myers: The power of anonymous allegations to affect democracy, justice and the political system

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: When a whistleblower gets caught …

Signing off, by Julian Baggini: From Kierkegaard to JK Rowling, a look at the history of literary pen names and their impact

The Snowden effect, by Charlie Smith: Three years after Edward Snowden’s mass-surveillance leaks, does the public care how they are watched?

Leave no trace, by Mark Frary: Five ways to increase your privacy when browsing online

Goodbye to the byline, by Edward Lucas: A senior editor at The Economist explains why the publication does not name its writers in print

What’s your emergency? By Jason DaPonte: How online threats can lead to armed police at your door

Yakety yak (don’t hate back), by Sean Vannata: How a social network promising anonymity for users backtracked after being banned on US campuses

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Blot, erase, delete, by Hilary Mantel: How the author found her voice and why all writers should resist the urge to change their past words

Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy, by Andrey Arkhangelsky: Ten years after investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya was killed, where is Russian journalism today?

Writing in riddles, by Hamid Ismailov: Too much metaphor has restricted post-Soviet literature

Owners of our own words, by Irene Caselli: Aftermath of a brutal attack on an Argentinian newspaper

Sackings, South Africa and silence, by Natasha Joseph: What is the future for public broadcasting in southern Africa after the sackings of SABC reporters?

“Journalists must not feel alone”, by Can Dündar: An exiled Turkish editor on the need to collaborate internationally so investigations can cross borders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Bottled-up messages, by Basma Abdel Aziz: A short story from Egypt about a woman feeling trapped. Interview with the author by Charlotte Bailey

Muscovite memories, by Maria Stepanova: A poem inspired by the last decade in Putin’s Russia

Silence is not golden, by Alejandro Jodorowsky: An exclusive translation of the Chilean-French film director’s poem What One Must Not Silence

Write man for the job, by Kaya Genç: A new short story about a failed writer who gets a job policing the words of dissidents in Turkey

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Europe’s right-to-be-forgotten law pushed to new extremes after a Belgian court rules that individuals can force newspapers to edit archive articles

Index around the world, by

Josie Timms: Rounding up Index’s recent work, from a hip-hop conference to the latest from Mapping Media Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

What ever happened to Luther Blissett? By Vicky Baker: How Italian activists took the name of an unsuspecting English footballer, and still use it today

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Aug 2016 | mobile, News and features, Youth Board

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

For the past six months the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board has attended monthly online meetings to discuss and debate free speech issues. For their final assignment we asked members to write about the issue they felt passionately about that took place during their time on the board.

Simon Engelkes – Terrorism and the media in Turkey

When three suicide bombers opened fire before blowing themselves up at Istanbul Atatürk airport on 28 June 2016, Turkey’s social media went quiet. While the attacks were raging in the capital’s airport, the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan blocked social networks Facebook and Twitter and ordered local media not to report the details of the incident – in which at least 40 people were killed and more than 200 injured – for “security reasons”.

An order by the Turkish prime minister’s office banned sharing visuals of the attacks and any information on the suspects. An Istanbul court later extended the ban to “any written and visual media, digital media outlets, or social media”. Şamil Tayyar, a leading deputy of the ruling Justice and Development Party said: “I wish those who criticise the news ban would die in a similar blast.”

Hurriyet newspaper counted over 150 gag orders by the government between 2010 and 2014. And in March 2015, Turkey’s Constitutional Court approved a law allowing the country’s regulator to ban content to secure the “protection of national security and public order” without a prior court order. Media blackouts are a common government tactic in Turkey, with broadcast bans also put in place after the bombings in Ankara, Istanbul and Suruç.

Emily Wright – The politics of paper and indirect censorship in Venezuela

Soaring inflation, high crime rates, supply shortages and political upheaval all typically make front-page news. Not so in Venezuela, where many newspapers have suspended printing because of a shortage of newsprint.

For over a year now, the socialist government of Nicolás Maduro has centralised all paper imports through the Corporación Maneiro, now in charge of the distribution of newsprint. It is a move the political opposition is calling a form of media censorship, given that many newspapers critical of Chavismo and Maduro’s regime, have been struggling to obtain paper to print news.

In January, 86 newspapers declared a state of emergency, announcing they were out of stock and their capacity to print news was at risk. El Carabobeño, which is critical of the government and Chavismo, stopped circulating in March due to a lack of paper. A year earlier the newspaper had been forced to change its format to a tabloid, and reduce its pages, after running as a standard newspaper since 1933.

Censorship is an long-term problem in Venezuela but it is taking new, covert forms under Hugo Chávez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro. Media outlets are being economically strangled through tight regulation. On top of this huge fines for spurious charges of defamation or indecency linked to articles have become commonplace. Correo del Coroni, the most important newspaper in the south of the country, went bankrupt in this fashion. In March it was fined a million dollars and its director sentenced to four years in jail for defamation against a Venezuelan businessman. A month earlier it was forced to print only at weekends after being systematically denied newsprint.

Under Maduro’s regime, censorship in Venezuela has gone from piecemeal to systemic and the public’s right to information has been lost in the mix. Unable to mask the country’s hard realities with populist promises like his predecessor did, Maduro has been cracking down on the media instead.

Reporters Without Borders recently rated the press in Venezuela as being among the least free in the world, ranking it 139 out of 180 countries, below Afghanistan and Zimbabwe. Freedom House recently rated the press in Venezuela as Not free.

Mark Crawford – The UK government’s anti-BDS policy

In February this year, the British government banned public boycotts of Israeli goods. In recent years, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign has become popular among those in opposition to the oppression of the Palestinian people, whereby Israeli goods, services and individuals are evaded or censored.

It’s illogical to punish an entire nation, as BDS does, for the actions of those in power. The answer to this illiberal policy must not be, however, to hand greater power to faceless, bureaucratic law enforcement to suppress freedom of expression.

As a result of the government’s clampdown, the board of trustees at my students’ union, UCLU, has already overridden a pro-BDS position democratically endorsed – however poorly – by its Union Council; but as well as emboldening the very illiberal voices that thrive on the aloof vilification of bureaucrats, the board even elected to censor council’s harmless and necessary expressions of solidarity with the Palestinian people.

The cure for faulty ideas and tactics is better ideas and better politics – translated through debate and honest self-reflection. Not only have legal shortcuts never worked, but they’re ideologically hypocritical and politically suicidal.

Ian Morse – Twitter’s safety council

Twitter unveiled its safety council in February. Its purpose is to ensure that people can continue to “express themselves freely and safely” on Twitter, yet there are no free speech organisations included.

So while the group ostensibly wants to create safety, its manifesto and practice suggest otherwise. The group doesn’t stop incitements of violence, it stops offensive speech. Safety only refers to the same attempts to create “safe spaces” that have appeared in so many other places. There is a difference between stopping the promotion of violence within a group – as Twitter did with 125,000 terrorism-related accounts – and stopping people from hearing other people’s views. Twitter has a mute and block button, but has also resorted to “shadow banning”.

Now compound this with the contradiction that is Twitter’s submission to authoritarian governments’ demands to take down content and accounts in places where not even newspapers can be a forum for free information, such as Russia and Turkey.

It’s indicative of two wider trends: the consolidation of “speech management” in Silicon Valley, and the calamitous division of the liberal left into those who allow the other side to speak and those who do not.

Layli Foroudi – Denied the freedom to connect: censorship online in Russia

The United Nations Human Rights Commission has brought the human rights framework into the digital age with the passing of a resolution for the “promotion, protection, and enjoyment of human rights on the internet”, particularly freedom of expression.

Russia opposed the resolution. This is unsurprising as the government institutionalises censorship in legislation, using extremism, morality and state security as justifications. Since November 2012, the media regulatory body Roskomnadzor has maintained an internet blacklist. Over 30,000 online resources were listed in April, plus 600,000 websites that are inaccessible due to being located on the same IP address as sites with “illegal” information.

This year, the internet in Russia has experienced increased censorship and site filtering under the influence of Konstantin Malofeev whose censorship lobbying group, the Safe Internet League, has been pushing for stricter standards in the name of Christian Orthodox morality, freedom from extremism and American influence.

Activists in Russia have claimed that their messages, sent using encrypted chat service Telegram, have been hacked by Russian security forces. Surveillance was what originally drove Pavel Durov, founder of Telegram and social network VKontakte, to set up the encrypted service as he and his colleagues felt the need to correspond without the Russian security services “breathing down their necks”. Durov himself lives in the US, a move prompted by the forced sale of VKontakte to companies closely aligned with the Kremlin, after the social network reportedly facilitated the 2011 protests against the rigging of parliamentary elections. His departure confirms theories about the chilling effect that crackdowns on expression can have on innovation and technology in a country.

In June a new law was passed which requires news aggregators, surpassing one million users daily, to check the “truthfulness” of information shared. Ekaterina Fadeeva, a spokesperson for Yandex, the biggest search engine in Russia, said that Yandex News would not be able to exist under such conditions.

Madeleine Stone – The murder of Joe Cox

The brutal daylight murder of Yorkshire MP Jo Cox may not initially seem like a freedom of speech issue.

Approached outside her constituency surgery on 16 June 16, at the height of the polarising Brexit debate, Cox was stabbed to death by a man who shouted “Put Britain first” as he attacked her. Cox was an ardent supporter of Britain remaining a member of the European Union, flying a “Stronger In” flag as she sailed down the Thames with her family in a dingy the day before her murder. Her passionate campaigning over the referendum should not have been life threatening.

In Britain, we imagine political assassinations to take place in more volatile nations. We are often complacent that our right to free speech in the UK is guaranteed. But whilst there are people intimidating, attacking and murdering others for expressing, campaigning on and fighting for their beliefs, this right is not safe. For democracy to work, people need to believe that they are free to fight for what they believe is right, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum. Jo Cox’s murder, which for the most part has been forgotten by British media, should be a wake-up call to Britain that our freedom of speech cannot be taken for granted.

16 May 2016 | Art and the Law Commentary, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, News and features

Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, participated in the Theatre UK 2016 conference on 12 May 2016. This is an adapted version of her presentation.

In January 2013 I organised a conference called Taking the Offensive for Index on Censorship, in partnership with the Free Word Centre and Southbank Centre. The conference was held to debate the growth of self-censorship in contemporary culture, the social, political and legal challenges to artistic freedom of expression and the sources of these new challenges.

The report from the conference concluded that censorship and self-censorship are significant influences in the arts, creating a complex picture of the different ways society controls expression. Institutional self-censorship, which many acknowledged suppresses creativity and ideas, was openly discussed for the first time.

Lack of understanding and knowledge about rights and responsibilities relating to freedom of expression, worries about legal action, police intervention and loss of funding, health and safety regulations, concern about provoking negative media and social media reaction, and public protests are all causing cultural institutions to be overly cautious.

One speaker at Taking the Offensive suggested that we are fostering a culture where “art is not for debate, controversy and disagreement, but it is to please”.

There is above all, unequal access to exercising the right to artistic freedom of expression, with artists from black and minority ethnic encountering additional obstacles.

Many felt that far greater trust, transparency and honesty about the challenges being faced need to be developed across the sector; dilemmas should be recast as a necessary part of the creative process, to be shared and openly discussed, rather than something to keep behind closed doors. This will make it possible for organisations to come together when there is a crisis, rather than standing back and withholding support: “if we collectively don’t feel confident about the dilemmas we face how can we move on with the public?”

I think there have been significant changes in the three years since the conference and, whilst I think the same challenges persist, there have been some really positive moves to tackle self-censorship within the sector. The growth of What Next? has created precisely the platform to debate and discuss the pressures, dilemmas and controversies that the conference identified. What Next? has produced guidance on navigating some of these issues and is developing more resources on how organisations can support each other when work is contested.

Index on Censorship responded to the clear call from the conference for the need for guidance about legal rights and responsibilities if we are to create a space where artists are free to take on complex issues that may be disturbing, divisive, shocking or offensive.

We have published information packs around five areas of law that impact on what is sayable in the arts: Public Order, Race and Religion, Counter Terrorism, Child Protection and Obscene Publications. They are available on the website under our campaign Art and Offence. These have been well received by the sector and read by CPS and police and we are developing a programme of training which will, if all goes well, include working with senior police officers.

At the same time, pressures from outside the sector have intensified.

The role of the police in managing the public space when controversial art leads to protest has come into sharp relief over the past two-three years where they have repeatedly “advised” venues to remove or cancel work that has caused protest or may cause protest.

I did a case study on the policing of the picket of Exhibit B at the Barbican in London which is available on the Index website; and in the same year, the Israeli hip hop opera the City was closed in Edinburgh on the advice of the police.

More worryingly the police “advice” has also led to the foreclosing of work that is potentially inflammatory – as in Isis Threaten Sylvannia an art installation by Mimsy, that was removed from an exhibition called Passion for Freedom from the Mall Gallery last year.

With the removal of Isis Threaten Sylvania, we see a shift from the police advising closure following protest to the police contributing indirectly or directly to the decision to remove work to avoid protest.

In this case freedom of expression was actually given a price — set at £7,200 per day for the five days of the exhibition — the price set by the police for their services to guarantee public safety.

The police took the view that a perfectly legal piece of art, which had already been displayed without incident earlier in the year, was inflammatory. And in the balance of things as they stand, this opinion outweighs:

- the right of the artist to express him or herself;

- the organisation’s right to present provocative political art;

- the audience’s right to view it;

- and those that protest against it, the right to say how much they hate it, including when that means that they want the art removed.

This new chapter in the policing of controversial art sets alarm bells ringing and represents a very dangerous precedent for foreclosing any work that the police don’t approve of.

But going against police advice is problematic.

In Index’s information pack on Public Order we asked our legal adviser, working pro bono, questions that many artists and arts managers are concerned about:

What happens if police advise you not to continue with presenting a piece of work because they have unspecified concerns about public safety – and yet tell you it is your choice and they can only advise you?

The artist would in principle be free to continue with the work. It would be advisable, however, to ensure that the reasons held by the police were understood. It may also be prudent to take professional advice…

And then what responsibilities for safety do employers have to staff and the public in relation to continuing with an artwork that has been contested by the police?

An organisation also has duties to their employees and members of the public on their premises. These duties may extend to making an organisation liable in the event of injury to a person resulting from the unlawful act of a third party if, for example, that unlawful act was plainly foreseeable – in other words the police have given their warning.

What are the options for an arts organisation to challenge police advice at the time of the protest itself?

If the organisation believes that it has grounds to challenge police directions to avoid a breach of the peace, it can seek to take legal action on an urgent basis. Realistically…legal action will not be determined until some time later and until it is determined by the courts, the organisation and/or its members or employees would risk arrest if they do not comply with police directions.

So – what starts out as police advice which implies genuine choice, on closer inspection transforms into a Hobson’s Choice where failure to follow that advice could lead to arrest.

On this evidence, both self-censorship and direct censorship are the undesirable outcomes of this as yet unchallenged area of policing.

But the Crown Prosecution Service has read and approved the packs and our law packs are in the system with the police.

The ideal policing scenario is to keep the space open for both the challenging political art and the protest it provokes. Both are about freedom of expression, what we have to avoid is the heckler’s veto prevailing.

Going back to other recent examples of censorship — questions remain about the role of the police in the decision to cancel Homegrown the National Youth Theatre production of a play about the radicalisation of young Muslims by writer Omar El-Khairy and director Nadia Latif. This was followed earlier this year by the presentation, without incident, of Another World: Losing our Children to Islamic State at the National Theatre, play on similar themes by Gillian Slovo and Nicolas Kent.

I mention Another World because it is important to state the obvious, that all the work that has been contested by the police and been cancelled, relates to work about race and religion and the majority of artists involved in work that has been foreclosed are from black and minority ethnic communities.

Looking through the lens of freedom of expression, each case of censorship gives a valuable opportunity to view a specific snapshot of relationships within society and to analyse the power dynamics operating there, both directly around the censored work — whose voices are and aren’t being heard in the work itself, and in the field and context in which the work is taking place and again looking at who is in control, who decides what voices are heard. I don’t have time here to go into an analysis of each case, but what emerges is that freedom of expression is, as it stands, a biased affair in the UK and I believe will remain so while our society and our culture are not equal.

As well as these new cases of censorship that we have seen since the 2013 conference, we have also seen new government policy, legislation and regulations which place increasingly explicit controls on what we can say and have a chilling effect on many areas of expression and communication, and interaction with government.

Many campaigners and charities see the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 as designed to deter charities from intervening in judicial reviews — the most important legal channel we have to call authorities to account; the Investigatory Powers Bill, better known as the Snoopers’ Charter gives the surveillance state more powers; the Prevent Strategy requires us to police each other – surveillance and policing our neighbours — two nasty authoritarian tactics, and most recently the anti-advocacy clause would effectively ban organisations from using government funds for lobbying — stifling dissent. It was due to come into law on 1 May but the consultation period was extended and it might be kicked into the long grass.

The government has made it clear that it wants us to see ourselves predominantly if not exclusively as businesses and in response we have successfully made the case that the arts contribute massively to the economy.

But we know we are so much more. The arts are a vital, at best magnificent and effective player in civil society — especially when you define civil society as “a community of citizens linked by common interests and collective activity”.

With our core values and freedoms under attack, the arts and other civil society bodies are responding. The discussion about the role of the artist in taking on the big issues in society — from climate change to the refugee crisis — has, from where I stand, definitely intensified and gone up the agenda over the past three years, both here and internationally, as the pressure on our freedoms and values also intensifies domestically and internationally.

To fully participate in society and to create art that calls power to account, we need to continue to identify, analyse and tackle the causes of self-censorship within the sector, and stand together to enter into dialogue with the various agents of control that we identify in the process.

Art can help us imagine and bring about a more equal and just future.

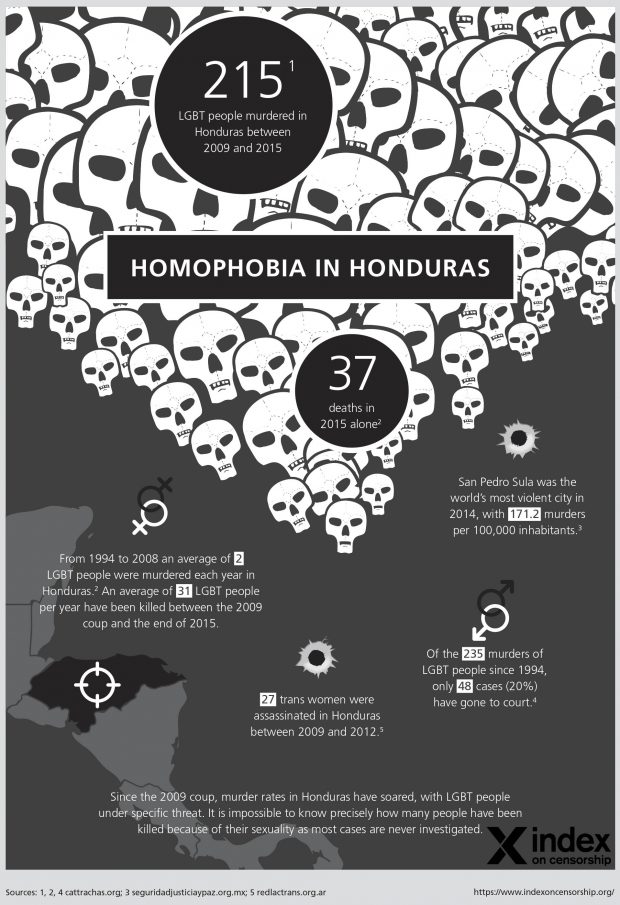

20 Apr 2016 | Americas, Honduras, Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016

[This article is also available in Spanish]

A year after returning from exile, Honduran gay rights activist Donny Reyes still fears a murderous attack at any minute.

“I’ve been imprisoned on many occasions. I’ve suffered torture and sexual violence because of my activism, and I’ve survived many assassination attempts,” he said, in an interview with Index on Censorship.

Activists in Honduras must contend with a constant barrage of threats and, often fatal, attacks. Reyes, the coordinator of the Honduran lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender advocacy group Arcoíris (Rainbow), had spent 10 months abroad for his own safety, but felt an obligation to return to the frontline of the fight against discrimination.

“To be able to continue with my personal life and my work I have to be conscious that [death] could come at any moment,” he said. “The truth is it doesn’t worry me anymore. What worries me is that things won’t change.”

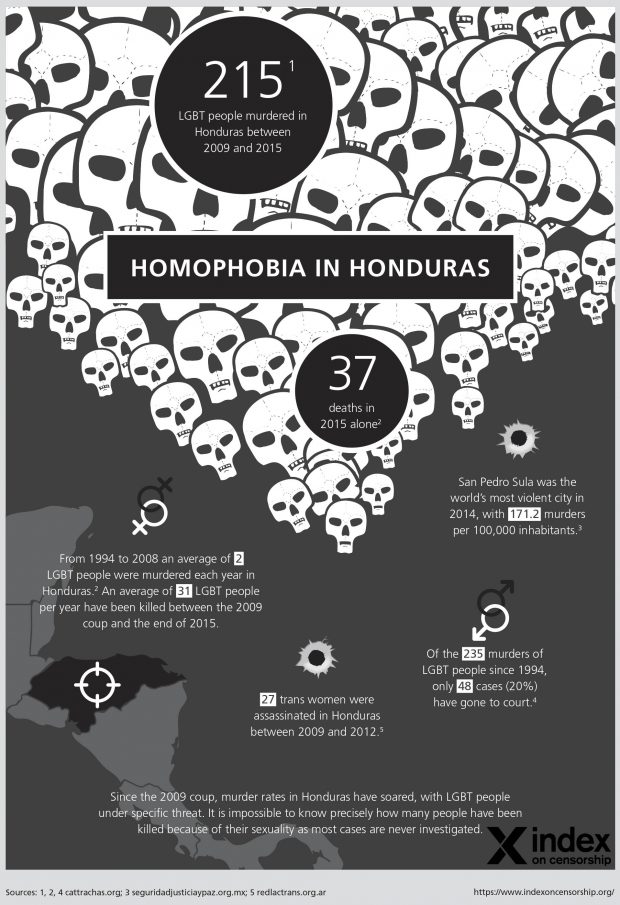

Dozens of LGBT Hondurans are murdered each year, with few of the killers brought to justice, according to figures from respected Honduran NGO Cattrachas. Journalists and activists who speak out are often attacked. One of these was Juan Carlos Cruz Andara who died after being stabbed 25 times by unknown assailants last June.

Arcoíris reported 15 security incidents against its members during the second half of 2015, including surveillance, harassment, arbitrary detentions, assaults, robberies, theft, threats, sexual assault and even murder. Other LGBT activists have experienced forced evictions, fraudulent charges, defamation, enforced disappearances and restrictions of right to assembly.

The activists consulted by Index all said that the level of homophobic violence exploded after the ousting of liberal President Manuel Zelaya in the military coup of 2009. The election of right-wing candidate Porfirio Lobo Sosa the following year coincided with the militarisation of Honduras, a rise in gang-related violence, and a clampdown on human rights.

The records from Cattrachas show that on average two LGBT people were murdered each year in the country from 1994 to 2008. After the 2009 coup that rate rocketed to an average 31 murders per year, according to figures from Arcoíris. In early 2016 there were signs the situation was escalating further with the murder of Paola Barraza, a member of Arcoiris’s group, on 24 January. In reality though it is impossible to know precisely how many people have been killed because of their sexuality because the vast majority of cases remain unsolved.

Erick Martínez Salgado, who volunteers with LGBT advocacy group Kukulcanhn, told Index that gay activists protested heavily against discrimination and the coup. He believes the government came to view his group as a threat to the traditional social order and started targeting them to “send a message” to other protesters.

One of the most prominent gay rights activists of the time, Walter Tróchez, was killed in a drive-by shooting in December 2009. Human rights groups noted that he had previously been kidnapped, beaten and threatened for demonstrating against the coup and advocating for gay rights. Four years later, Tróchez’s friend and fellow gay rights activist Germán Mendoza was arrested and charged with his murder.

Mendoza told Index he was held in deplorable conditions and repeatedly tortured in a bid to make him plead guilty. Eventually he was released after proving his innocence last year. Mendoza believes he was arrested because the government wanted to use him “as a scapegoat to wash their hands of the responsibility” for Tróchez’s death, which remains unsolved. The Honduran government did not respond to requests for comment.

Gang warfare was a massive contributor to Honduras status as the nation with the world’s highest murder rate in 2012, however the gay community’s main concern is not gangs, but the state security forces.

“The police constitute the primary perpetrator of violations of the rights of the LGBT community,” the Coalition Against Impunity, an alliance of 29 Honduran NGOs, warned last year, citing alleged “police policy of frequent threats, arbitrary arrests, harassment, sexual abuse, discrimination, torture and cruel or degrading treatment”.

As a result many vulnerable activists are reluctant to ask for protection, for fear that contact with the police would expose them to greater security risks or reprisals.

The journalists who document homophobic violence in Honduras also risk their lives. Dina Meza, an independent investigative reporter who has covered the issue extensively, was nominated for an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award in 2014 for her journalism. Meza said the country’s mainstream media often portrays the LGBT community in a negative light.

Meza, who launched the independent news site Pasos de Animal Grande last year to draw attention to the hardships facing the most vulnerable sectors of society, said reporters who cover violence against the LGBT community are also targeted. She said not only do journalists get physically assaul-ted by the security forces and expelled from public events, but they are also targets of government-led smear campaigns.

“It’s extremely common here for them to link human rights defenders to drug trafficking and organised crime, in a bid to sow doubts in people’s minds about the work that we’re doing,” she explained. “If we speak out at an international level they say we’re trying to undermine Honduras, discourage investment and see the country burn.”

Peter Tatchell, director of the London-based LGBT campaigning group the Peter Tatchell Foundation, called for the world to pay more attention to the killings. He said: “This extensive, shocking mob violence against LGBT Hondurans is almost unreported in the rest of the world. The big international LGBT organisations tend to focus on better-known homophobic repression in countries like Egypt, Russia, Iran and Uganda. What’s happening in Honduras is many times worse. Is this neglect because it is a tiny country with few resources and no geo-political weight? The UN, Organisation of American States and foreign aid providers need to do more to press the Honduran government to crackdown on anti-LGBT hate crime and to educate the public on LGBT issues to combat prejudice.”

Meza and the activists interviewed by Index also believe that Catholic and Evangelical Christian groups have become increasingly influential in Honduran society. Reyes from Arcoíris described the state, the church and the mainstream media as a triumvirate which has fuelled “impunity, fundamentalism, machismo and misogyny” across the country, with disastrous consequences for the LGBT community.

“At home and at school are the first two places where we’re attacked and discriminated. We flee home at very young ages because the family is built on religious values. Our families punish us in a cruel manner and this has a terrible psychological impact,” Reyes said. “Our educational and employment opportunities are diminished every day. We can be sex workers or street vendors, or stay in the closet in the hope of getting a job, but if they find out about your sexual orientation you’ll almost certainly be fired.”

Despite the risks he and his fellow activists face, Reyes said the drastic need for change is what gives them the strength to keep fighting discrimination: “We need a Honduras that’s free from violence and homophobia. We believe it’s our responsibility to fight for this so the next generation have a space to live in a better world.”

This article is from the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (free trial or £18 for the year). Copies are also available at the BFI and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]