11 May 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Letters

E. Belit Sağ is a Turkish activist and artist

It was my intention for a long time to publish a statement about the censorship of my video Ayhan and me (2016), part of the group exhibition Post-Peace that was censored by Akbank Sanat. When the exhibition was censored, I wanted to prioritise the group statement of the collaborators and artists of the exhibition. The group statement is out, and it’s now my turn. I would like this statement to be seen as a contribution to the statements made by Katia Krupennikova, the curator of the show; the jury of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015; Anonymous Stateless Immigrants Movement; and the artist and contributors of the exhibition Post-Peace. With this statement, I aim to share my own experience.

I am the only artist from Turkey that was supposed to take part in the group exhibition Post-Peace. My initial proposal was specifically about Turkey. This proposal went through a censorship process starting months before the originally planned opening date. I’d like to share my experience with the hope that it will shed a little bit of light on the censorship that of the exhibition itself and the problem of censorship in the art field more generally.

The group exhibition Post-Peace was initially planned to take place in Amsterdam. I was invited by the curator at this early stage. Later on, with this exhibition concept, Katia Krupennikova applied for and won the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015. The exhibition moved from Amsterdam to Istanbul. In one of the talks Katia had with Akbank Sanat managers in November 2015, she mentioned to them my proposal. They told Katia that the political situation in Turkey is tense and that they can not commission the proposed work. Katia asked for an official statement from the director of Akbank Sanat, Derya Bigalı. She didn’t receive a reply. I met Katia when she came back to Amsterdam. We wrote together to Zeynep Arınç from Akbank Sanat, with whom Katia has been in contact throughout the process. We asked for a formal rejection letter from the director, explaining the reasons for their decision. Zeynep Arınç replied to our email informally telling Katia that Akbank Sanat can not commission this work.

My initial work proposal, censored by Akbank Sanat, was about Ayhan Çarkın. Ayhan Çarkın was part of JITEM, an unofficial paramilitary wing of the Turkish Security Forces active in mass executions of the Kurdish population in the 1990s. As a part of the deep state and JITEM, Ayhan Çarkın confessed in 2011 that he led operations that killed over 1000 Kurdish people during the 1990s. These confessions were made on television, and videos from those confessions are accessible on Youtube. The work I was planning to make was about Ayhan Çarkın’s personal transformation, how historical reality is constructed, and how to think about the term ‘evil’. This work, which was only a written proposal at that point, was censored by Akbank Sanat, even though it was part of the curator’s exhibition concept from the very beginning, and was chosen by an international jury as part of the exhibition for Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015.

This was the first time something like this had happened to me. Instead of leaving the exhibition, Katia and I came up with a proposal for a new work. The new work was going to talk about the censorship of my previous proposal, as well as the politics of images of war in Turkey. Akbank Sanat requested to see the script of this new work. Katia didn’t respond to this request, and I told her that I’m not in favour of showing the script, due to Akbank Sanat’s attitude up till that point. Consequently, we asked the founder of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition, curator Başak Şenova, for her opinion on this issue. At first she supported us, but after she consulted with Akbank Sanat she told us that the refusal by Akbank Sanat is understandable. To be honest these reactions made me feel alone. Turkey is really going through a tough period, and I started questioning why, as an artist, I was putting the whole institution at risk.

In December before I started producing my second proposal I realised that I did not feel comfortable with accepting the situation as it was. I decided to make the censorship public, by writing a letter and sending it to the press. I met with Katia and we started writing an email explaining the situation to the jury. In mid-January, before we finalised the letter, Katia told me that she talked to Akbank Sanat and they agreed to the new proposal and no longer demanded to see the script in advance. I started making the video. I got in contact with Siyah Bant, a group that deals with censorship in the field of art in Turkey. I got a lot of support from them, which helped against the feeling of isolation such censorship cases cause. Also, we started thinking about ways to deal with this specific case. The final video took shape as a result of this process. I believe watching the video complements this statement.

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

The video was finalised on 23 February, and Katia Krupennikova presented all the works to Akbank Sanat for a technical check on the same day. The exhibition was supposed to open on 1 March, and it was cancelled/censored on 25 February. There was no exhibition announcement on Akbank Sanat’s website or social media accounts, or there was any exhibition poster at Akbank Sanat’s space at any point. This makes me think that Akbank Sanat has been considering this decision for a long time, but didn’t communicate it to the curator or any other contributor of the show.

I don’t know and will never get definite confirmation whether the cancellation of Post-Peace was related to the content of my work or not. However, this does not change what happened. Together with Siyah Bant, we prepared a press release explaining the censorship prior to the cancellation of the exhibition. Even if the exhibition had not been cancelled, I was planning to publicise my experience of Akbank Sanat’s censorship.

In the 90s, Akbank Sanat hosted a painting exhibition by Kenan Evren. Kenan Evren is the leader of the 1980 coup d’etat in Turkey. Akbank Sanat has had several censorship cases in its history. Akbank Sanat gave Kenan Evren the possibility to exhibit his work as an “artist”, without questioning his leading role in the 1980 coup, from which the country still suffers. Akbank Sanat has never taken responsibility for this exhibition nor the role they took in it and what it means for Turkey. I do not believe that Akbank Sanat has or aims to acquire the ethical and conceptual capacity to host any exhibitions. The Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition that they have sponsored for the past four years is an important award in the international art world, which gives them a prestige they do not deserve.

At this point I have a number of questions to ask:

– Why does Akbank Sanat have the right to bypass the jury of Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015 and the originally accepted plan of the exhibition? As mentioned in Başak Şenova’s statement following the cancellation: “Afterwards, Akbank Sanat unquestioningly implements all aspects of the exhibition”

– How does Akbank Sanat position itself in relation to the jury of the competition, the founding curator, the curator, and the artists of the exhibition?

– Why didn’t Akbank Sanat discuss the possibility of cancelling the exhibition together with the curator, the artists and the jury prior to the cancellation? Why does Akbank Sanat take decisions from the top, thereby marginalising the contributors and blocking their participation in decision-making mechanisms concerning the very exhibition they have been commissioned to make?

Institutions like Akbank Sanat will not admit that they censored the content of any exhibition, and will not take responsibility for the situation. These institutions interfere with cultural content due to their connections to corporations and banks, allied with oppressive government policies. This paves the way for normalising censorship and abusing the political situation of the country as an excuse, as in the text explaining the cancellation by the director of Akbank Sanat (“Turkey is still reeling from their emotional aftershocks and remains in a period of mourning.”).

I believe we need to expose these government-allied mentalities and structures over and over again. Institutions like Akbank Sanat can continue their activities because every time they censor the cultural arena they get away with it; their acts are not revealed, they are not held accountable, and they continue to receive support. Letting this happen deserts the fields of culture and art, and distances them from the struggles going on in the country. At the same time, this acceptance and silence obstructs those people and institutions that bravely resist, and further restricts already shrinking zones of freedom. We, as cultural and art workers, can counter this by refusing to accept the silencing of artistic expression.

Any cultural and art worker who is ignorant of the ongoing oppression in Turkey, who does not call censorship by its name, who does not see or fails to recognise the ongoing massacres in Kurdish lands becomes part of this oppressive structure. I have channels to speak out, I do not want to intimidate people who don’t have access to such channels, or who have to stay silent in order to avoid risking their lives. It is exactly for this reason, that we have to speak out en masse. I also think that ‘speaking out’ can happen in a variety of ways, just as acts of resistance do.

Although I have a hard time believing it myself, almost everyone I met in Cizre (a Kurdish town inside Turkey bordering Syria) in 2015, has either been killed or else left Cizre in order to stay alive. I owe this statement to the people I met in Cizre. Many other Kurdish towns and cities have suffered from or are currently undergoing similar attacks by Turkish State security forces. Every struggle in this region is connected, even though some might want to separate them. The one sharp difference is that some people get censored and others get killed in this country. Exactly because of this, we, the ones who get censored, need to keep ourselves connected to other resistances and realise of our privilege.

With this letter I wish to show solidarity with those working in the fields of culture and art who have already experienced or might experience similar censorships. My statement aims to express that we do not have to bear those abuses alone, with the hope that more of us will be able to speak up, and the hope that we can act collectively.

24 Feb 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

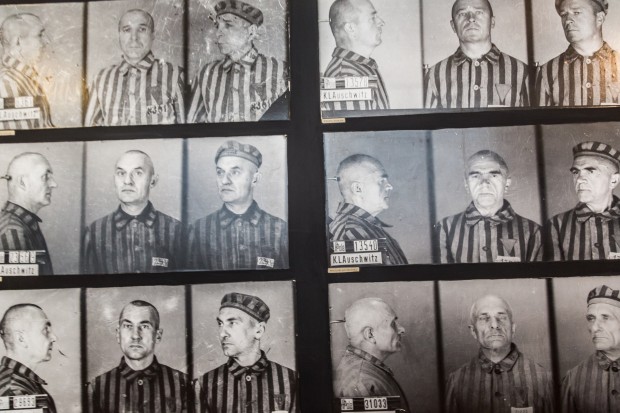

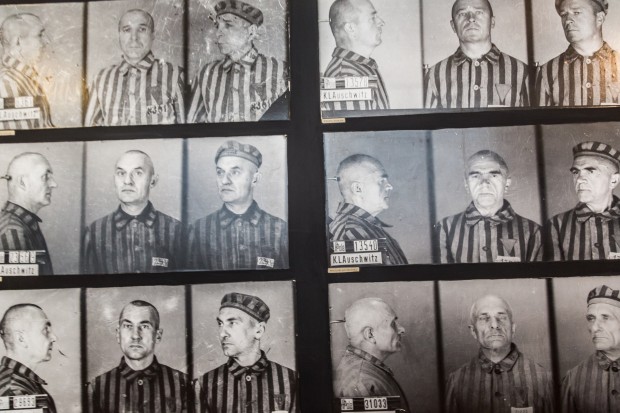

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship

16 Feb 2016 | Art and the Law, Art and the Law Guides, Campaigns

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”94435″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]This guide is also available as a PDF.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Preface

Freedom of expression is essential to the arts. But the laws and practices that protect and nurture free expression are often poorly understood both by practitioners and by those enforcing the law. The law itself is often contradictory, and even the rights that underpin the laws are fraught with qualifications that can potentially undermine artistic free expression.

As indicated in these packs, and illustrated by the online case studies – available at indexoncensorship. org/artandoffence – there is scope to develop greater understanding of the ways in which artists and arts organisations can navigate the complexity of the law, and when and how to work with the police. We aim to put into context the constraints implicit in the European Convention on Human Rights and so address unnecessary censorship and self-censorship.

Censorship of the arts in the UK results from a wide range of competing interests – public safety and public order, religious sensibilities and corporate interests. All too often these constraints are imposed without clear guidance or legal basis.

These law packs are the result of an earlier study by Index: Taking the Offensive, which showed how self-censorship manifests itself in arts organisations and institutions. The causes of self-censorship ranged from the fear of causing offence, losing financial support, hostile public reaction or media storm, police intervention, prejudice, managing diversity and the impact of risk aversion. Many participants in our study said that a lack of knowledge around legal limits contributed to self-censorship.

These packs are intended to tackle that lack of knowledge. We intend them as “living” documents, to be enhanced and developed in partnership with arts groups so that artistic freedom is nurtured and nourished.

Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive, Index on Censorship[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”94431″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Foreword by Topher Campbell

My mission as an artist is to represent and explore work that is inspired by difference, identity and sexuality. As a black gay man this means that I make work that intersects between different points of cultural interest that are often marginalised by mainstream institutions. In the UK, where white people lead the overwhelming majority of arts-producing companies and institutions, there are huge barriers delineating what kind of art, performance or writing people of colour produce. This means there becomes work that is considered acceptable and work considered either offensive or irrelevant. We only need to look at who is in “The House” and who is in “The Field” to see how little has changed.

In creating work for the stage, film and exhibition I am struck by the language used to censor work or deny even that the work has any value in a cultural context. Often stated is the idea that there are no black or/and gay people “in our audience”, “on our data base”, “in our readership” who would be interested in “your work”.

Other excuses are that institutions and commissioners have no knowledge of the historical or cultural context of the work and therefore do not see its value. Then there is funding censorship, which works like a two-edged knife. Where a lack of work from BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) or LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgendered, Queer) people is considered, funding is easier.

However, often this is policed in terms of what is socially acceptable, rejecting complex explorations of sexual content or content that critiques the white or black hegemony of victimhood and the outsider. Basically what white and black straight funders and programmers can’t connect with, they ignore.

Being shut out of performance or exhibition space or repeatedly turned down for funding (something that disproportionately affects people of colour) means no chance to exhibit work or share perspective. It means my work struggles for credibility in the UK when looking for a home. It remains marginal and therefore invisible. The reality of how this works is subtle. Different institutions and personalities nuance it. But the effect is blunt.

Increasingly BME and LGBTQ artists and those who seek to challenge the status quo either give up or decide to leave the UK. Many head for the US where a more open conversation about race and sexuality is possible. This means that for all our boasting about the rich diversity of the UK, we are actually making our culture poorer, smaller.

Topher Campbell is a director of film, television and theatre. He is currently the artistic director of The Red Room Theatre Company and chair of the Independent Theatre Council UK.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is a UK common law right, and a right enshrined and protected in UK law by the Human Rights Act(1) , which incorporates the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law. The most important of the Convention’s protections in this context is Article 10.

ARTICLE 10, EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

- Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent states from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

- The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

|

It is worth noting that freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning it must be balanced against other rights.

Where an artistic work presents ideas that are controversial or shocking, the courts have made it clear that freedom of expression protections still apply.

As Sir Stephen Sedley, a former Court of Appeal judge, explained: “Free speech includes not only the inoffensive but the irritating, the contentious, the eccentric, the heretical, the unwelcome and the provocative provided it does not tend to provoke violence. Freedom only to speak inoffensively is not worth having.” (Redmond-Bate v Director of Public Prosecutions, 1999).

Thus to a certain extent, artists and galleries can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock, disturb and offend.

As is seen above, freedom of expression is not an absolute right and can be limited by other rights and considerations. While the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and police have a positive obligation to promote the right to freedom of expression, they also have a duty to protect other rights: to private and family life, the right to protection of health and morals and the protection of reputation.

The following sections of the pack look at elements of the law that may curtail free expression: race hatred and hatred on grounds of religion or sexual orientation.

| HATE SPEECHThe case law of the European Court of Human Rights identifies certain forms of expression that are contrary to the Convention and therefore not protected by Article 10.

These include racism, xenophobia, antiSemitism, aggressive nationalism and discrimination against minorities and immigrants. The court is “particularly conscious of the vital importance of combating racial discrimination in all its forms and manifestations”.

On the basis of these principles, the court has upheld convictions for protesting against “the Islamification of Belgium”, publishing leaflets advocating a white-only society and displaying a poster portraying the Twin Towers on fire with the words “Islam out of Britain – Protect the British People”.

However, the court aims to distinguish between genuine and serious incitement to extremism and violence, on the one hand, and the right of individuals to offend, shock and disturb, on the other.

The court has also stated that people who hold religious beliefs “cannot reasonably be exempt from all criticism” and “must tolerate and accept the denial by others of their religious beliefs and even the propagation by others of doctrines hostile to their faith”. |

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”94434″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

Race and protected characteristics offences explained

UK law criminalises conduct that has the intent of stirring up racial hatred or hatred on grounds of religion or sexual orientation. “Conduct” includes the use of hateful words, but also a broad range of expression, such as displays of text, books, banners, photos and visual art, the public performance of plays and the distribution or presentation of pre-recorded material. In all three cases a magistrate can grant the police a warrant to seize any material that is hatefully inflammatory.

On summary conviction, offenders may face up to six months’ imprisonment, a fine or both. The more serious indictable offences may be tried by jury, but on conviction the offenders face up to seven years’ imprisonment, a fine or both. All prosecutions must be approved by the Attorney General (the government’s chief law officer).

RELEVANT DOMESTIC LEGISLATION

- Race Relations Act 1965

- Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE)

- Public Order Act 1986

- Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (CDA) as amended by the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Disorder Act 2001 – Section 31- racially or religiously aggravated public order offences.

- The Human Rights Act 1998

- Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006

- Equality Act 2010

|

The various offences were established in the wake of decades of efforts to challenge discrimination in the UK. The Race Relations Acts of 1965, 1968 and 1976 applied increasingly stronger measures to prevent discrimination on the grounds of race, colour, nationality, ethnic and national origin in employment, provision of goods and services, education and public services.

The Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000 further included a statutory duty on public bodies to promote race equality, and to prove that action to prevent race discrimination was effective. The act was repealed by the Equality Act 2010, which consolidated existing anti-discrimination law in the UK to bring it in line with European Commission directives on equal pay, sex and disability discrimination and the Race Relations Act.

The introduction of new legislation to criminalise religious hatred caused concern among the creative community, specifically prohibitions under Sections 18-29AB of the Public Order Act 1986, as amended by Schedule 1, Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 and section 74 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008. English PEN and a number of free expression groups lobbied for further amendments to protect free speech from inappropriate use of the act.

| PEN AMENDMENT

Section 29J of Part IIIA (the so-called ‘PEN amendment’) states that the rules on public order must not be applied “in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system”.

The courts are also required by other laws, including the 1998 Human Rights Act, to pay particular regard to freedom of expression when addressing charges of racially or religiously aggravated offences, or aggravated on grounds of sexual orientation. |

Racial hatred

Racial hatred is defined in Section 17 of the Public Order Act 1986 as “hatred against a group of persons … defined by reference to colour, race, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origins”.

Artists, producers or presenters of public performances or exhibitions may commit an offence under Section 18 of the act if their artistic expression involves the use of threatening, abusive or insulting words, images or actions that are intended to – or, having regard to all the circumstances, are likely to – stir up racial hatred.

However, the alleged offender has a defence if:

- It cannot be proven that the work was intentionally threatening, abusive or insulting and/or the artist or presenter was not aware that the content might be so received;

- It can be proven that the work was presented inside a private dwelling and that the artist had no reason to believe that the work would be heard or seen by persons outside it.

Religious hatred and hatred on grounds of sexual orientation

Religious hatred is defined in section 29A of the Public Order Act 1986 as “hatred against a group of persons defined by reference to religious belief or lack of religious belief”.

Hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation is defined in section 29AB as “hatred against a group of persons defined by reference to sexual orientation (whether towards persons of the same sex, opposite sex or both)”.

It may be an offence under Section 29B of the Public Order Act 1986 if artworks involve the use of threatening, insulting or abusive words, images or actions, that are intended to – or are likely to – stir up hatred on the grounds of religion or sexual orientation. It is an offence to intentionally stir up religious hatred by using threatening words or behaviour, including in an artistic context.

It is important to note that the offences related to hatred of religious groups or sexual orientation are more narrowly defined than racial hatred offences in two specific ways.

First, unlike racial hatred offences, offences related to hatred of religious groups or sexual orientation apply only where the words, images or conduct are threatening. No offence is committed by using words, images or behaviours that are merely insulting or abusive. An act is likely to be considered “threatening” if it is clearly intended to place people in fear for their safety or wellbeing.

Words or actions that are merely intended or likely to upset, shock or offend are unlikely to count as “threatening”. The distinction was made to single out racially charged conduct as requiring greater censure(2) .

Secondly, actual intention must be proven in cases of hatred of religious groups or sexual orientation. The mere likelihood that it might stir up hatred, or even the fact that it did, is not sufficient for a conviction in respect of religion and sexual orientation. The intention here is to differentiate between this kind of hatred and racial hatred. In the latter case, the prosecution is not required to prove the state of mind or actual intent of the offender. This means that the racial hatred offences prohibit a much broader range of conduct.

Hatred offences will also be committed in respect of race, religion or sexual orientation for:

- Publishing or distributing written material stirring up racial or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation.

- Public performance of a play stirring up racial or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation.

- Distributing, showing or playing a recording stirring up racial or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation.

- Broadcasting a programme stirring up racial or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation.

- Possession of written material or recording stirring up racial or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation.

The term “written material” refers to “any sign or visible representation” and therefore includes imagery, paintings or other forms of physical artistic expression.

Religious and racially aggravated public order offences

There are also further offences under the Public Order Act 1986 that are described as “racially or religiously aggravated”. Section 28 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 sets out what it means for an offence to be “racially and religiously aggravated”: there must be a demonstration of hostility on the basis of a membership of a racial or religious group or the particular offence must be motivated by the same hostility.

Offences that may be racially or religiously aggravated are:

The offence of causing fear or provocation of violence contrary to Section 4 of the Public Order Act 1986: When a person uses threatening, insulting or abusive words or behaviour; or distributes or displays threatening, insulting or abusive writing, signs or other visible representation, with the intention to cause belief that immediate unlawful violence is imminent, or to provoke it; or to do so in circumstances where such belief would be likely. The offence can be committed in public or in private but not in a “dwelling” or living accommodation.

The term “writing” covers typing, printing, lithography, photography and other means of reproducing words. “Displays”, read in the context of the Section 4 of the Public Order Act 1986, would require it to be publicly visible, that is, not in a home.

Causing harassment, alarm or distress contrary to Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986: Where a person uses threatening or abusive words or behaviour; or distributes or displays threatening or abusive writing, signs or similar, within the hearing or sight of a person who is likely to be caused harassment, alarm or distress as a result.

It is a defence to prove that the accused had no reason to believe that there were people within hearing or sight likely to be affected, or that he was inside a home and was similarly out of sight and earshot. It is also a defence to argue that the conduct was “reasonable” in the circumstances. No proof of the conduct being actually heard or seen is required. But the prosecution must prove that the defendant intended to be threatening, insulting, abusive or disorderly, or was subjectively aware that his or her conduct could be characterised that way.

Intentionally causing harassment, alarm or distress contrary to Section 4A of the Public Order Act 1986: This offence is in fact a more serious alternative to Section 5. It involves conduct similar to that outlawed by Section 5 but in addition requires proof of intention to cause harassment, alarm or distress and proof that harassment, alarm or distress was actually caused. The defendant can claim in defence that the act was carried out in a home in the belief that it was out of sight or earshot, or that the conduct was reasonable.

For example: A satirical animation depicting an identifiable person desecrating a religious symbol may involve the use of insulting words that cause distress to that person. If the use of the insulting words are considered unreasonable then this may constitute an offence under the Public Order Act 1986 if it was conducted outside a home. Further, if the artist demonstrates hostility towards the subject on the basis of their membership of a particular religious group then this may amount to a religiously aggravated public order offence. The courts have said that distress requires “real emotional disturbance or upset,” while harassment must be “real” as opposed to “trivial”.

Whether particular words or actions are reasonable will depend on all the circumstances of the case, the context in which they take place, the artist’s reasoning and any existing relationship between the artist and the subject. A gratuitous insult is more likely to fall foul of the criminal law than a genuine attempt to express an opinion on a matter of public interest.

The Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 prohibits discrimination, both by public bodies or private individuals, against certain classes of persons. The conduct outlawed by and defined in the Equality Act 2010 includes discrimination, harassment and victimisation. The Equality Act 2010 does not create criminal offences. Breaches of the relevant provisions can only result in declarations or mandatory orders and the award of damages. Many arts organisations may in fact be “public authorities” within the meaning of the act and should consult the Equality and Human Rights Commission to see if the act applies to their organisation(3). Further information can be found at the Equality and Human Rights Commission website: http://j.mp/sectorguidance.

The Equality Act 2010 has been described as harmonising or consolidating legislation by bringing together statutory protections against discrimination of different kinds under multiple acts and statutory instruments. It prohibits discrimination on the grounds of one or more “protected characteristics”. These are age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”94433″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

The powers of the police and prosecuting authorities

The police have statutory and common law powers to deal with racial and religious hatred offences and threats to public order. They can do so by making arrests for various offences, and by making arrests or giving directions to persons to prevent an offence from being committed, including a breach of the peace (for more information about breach of peace see the Public Order pack). In certain cases, they may also take a view whether or not public order offences were further aggravated by hostility on grounds of race, religion or sexual orientation.

In exercising these powers, the police also have duties to protect the free speech rights of all groups and individuals, and any other relevant freedoms, including the right to protest and to manifest a religion.

The role of the police naturally shifts with changes in culture and the law. The current position is that the police, as a public authority, have an obligation to ensure law and order and an additional obligation to preserve, and in some cases to promote, fundamental rights such as the right to protest and the right to freedom of expression protected by Articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights, currently incorporated into the UK’s domestic law.

The result is that the police conduct a pragmatic balancing act between the different parties and public interests. However, where public order issues arise, the policing of artistic expression is very much part of the police’s core duties and, as a public body, the police must discharge their duties. If arrests have been made, the CPS will consider whether, based on the evidence supplied by the police, there is a realistic prospect of conviction. If so, the CPS will consider whether it is in the public interest to prosecute, taking into consideration the competing rights of the artist, museum, theatre or gallery and others.

| JUDICIAL REVIEW

Actions by the police and the authorities are subject to review by the courts. Convictions can only be imposed by a court, and may in turn be appealed. Police actions may also be reviewed. In general terms, the test on such a review is whether, in light of what the police officer knew at the time, it was reasonable to take appropriate action under the law. The information made available to the police by an artistic organisation or artist before an incident may occur is therefore critical to the officer’s, and the court’s, assessment. https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/you-and-thejudiciary/judicial-review/ |

Because of their sensitive nature, prosecutions for stirring up racial and religious hatred can only be brought with the consent of the Attorney General even if the CPS considers there is enough evidence and it is in the public interest to prosecute. However, to date, no works of art have been tested in UK courts under laws proscribing hatred of race, religion or sexual orientation, so it is difficult to assess how this legislation would be applied in practice.

Under the law as it stands, offences under Sections 5, 4 and 4A of the Public Order Act 1986 (see previous section) can only be tried in the magistrates court. They are punishable by a fine and a maximum term of six months jail.

Section 4 and 4A Public Order Act offences that are “racially or religiously aggravated” are considered more serious offences and can be tried on indictment in the Crown Court. They are punishable by a maximum term of imprisonment of two years. A racially or religiously aggravated Section 5 offence is only triable in the magistrates court and is punishable by a fine only.

Higher maximum penalties of seven years apply to specific acts of hatred of race, religion or sexual orientation on conviction, compared with two years for public order offences merely aggravated by such hatred. These specific hatred offences require proof of intention to stir up racial hatred, unlike the lesser cases of aggravated offences, where simple proof of hostility is sufficient.

| TEST OF REASONABLENESS

A standard of “reasonableness” involves a balancing of factors and competing interests, and the line is not clear-cut. Assessing it in the realm of artistic expression, will take account of a range of factors, including protections under the European Convention on Human Rights. The clearer it is made that the work has artistic purposes, the greater weight this factor would be likely to carry. Another factor will be the willingness (especially as apparent to the police) of the artist to consider ways of mitigating hostile reaction that may result and the willingness of those opposed to the work to accommodate the artist’s right to free expression under certain restrictions. |

Additional Notes

To ensure that the expression of a view about the marriage of same-sex couples does not become an offence, there is a specific provision in the Public Order Act as it applies to England and Wales, that “discussion or criticism of marriage which concerns the sex of the parties to marriage shall not be taken of itself to be threatening or intended to stir up hatred”. In Scotland, the Lord Advocate has published “Prosecution Guidance in Relation to Same Sex Marriage” with the same effect.

In Scotland, only the parts of the Public Order Act prohibiting racial hatred are in force. Scotland has its own legislation for racial harassment and other forms of hate crime in respect of religion, sexual orientation, transgender and disability(4). Separate amendments apply to Northern Ireland; please refer to the Equality Commission Northern Ireland website(5).[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Practical guidance for artists and arts organisations

This guidance may apply if you are considering the creation or presentation of works that address sensitive topics connected to race, religion or sexual orientation. The aim of this process is to build the capacity of all involved to respond to criticism of controversial content, defend the right to freedom of expression and promote the right of audiences to share in a diversity of work and perspectives.

It should be noted the penalties for incitement to racial hatred are greater than those involving incitement to hatred of religious or sexual orientation. Note in particular the special protection afforded to expression to criticise, ridicule, insult, abuse and express dislike of particular religions, religious practices and believers contained in sections 29J and 29JA of the Public Order Act 1986 respectively (See the PEN amendment).

Presenting work that takes on sensitive issues around race, religion and sexuality has been at the heart of the majority of controversies in recent times in the UK. There are case studies of relevant works at indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence, some of which have been successfully presented and others which have been cancelled as a result of protest.

None of the works were removed on grounds of the content being illegal. However, if the work does contain words or images that may be threatening, insulting or abusive consider if it is likely (as opposed to merely possible) that they will stir up racial or religious hatred. If you have concerns that the work, or aspects of the work, may be in breach of race or religious hatred legislation then you should consult a lawyer.

In the main, as we see from recent cases, the arts organisation’s concern will likely be the reaction of third parties to the work, which may result in protest. In order to give the work the best chance of being successfully presented, it is important to think carefully about how the work could be received by different groups.

If you are considering engaging with local groups at an early stage, it is important that you are clear whether you are able or willing to adapt the artwork in the light of external comment, or if you are standing by the original work and simply wish to communicate its context. Consider providing people with critical perspectives a platform for balanced counter-speech, such as a post-event debate.

In the most contentious cases efforts to reach accommodation may simply be thwarted or continue to face significant opposition. Consideration must be given to how representative of sections of the community or the wider community those who object are. Some sub-groups may often claim – or assert the right to – speak on behalf of minority groups without clear authority. The concerns of the various constituencies within minority groups thus may be obscured. This will make attempts to engage with a wider and more representative crosssection of the relevant community more effective and valuable.

Consider the following preparatory steps:

- Make your motivation and reasons for making or displaying the work clear and why you consider the work to have artistic merit.

- Provide the context for the work, what the artist is seeking to achieve, their previous work and the role of controversy in their work.

- Consider the public interest in this work and how it contributes to a wider debate in society. Remember that the right to freedom of expression includes the right to express ideas and opinions that shock, offend and disturb.

- Consider advising audiences that the work features challenging material relating to race, religion or sexual orientation.

- Take account of the physical surroundings of the event, in particular the venue itself. A risk assessment should consider the potential dangers to the public in the case of protest, such as narrow accesses, structural instability or plate glass, for example.

- Take account of the impact on staff, the need for special training and the possible costs of additional security. See the Behud case study at indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence.

- Establish relations with the appropriate police officer responsible for race relations or hate crime in your area. A good relationship could be invaluable at a later stage.

The promotion and use of good practice in this area will be beneficial to all involved and help create communities of support among other artists and venues if controversy or prosecutions emerge. As a matter of good practice you might want to prepare a commitment to artistic and intellectual freedom of expression – before any controversy arises. (See box for a model draft based on a template by the National Coalition Against Censorship / www.ncac. org.)

This could be accompanied by a policy that sets out the way you will handle controversial exhibitions or performances. The policy should include clear creative and managerial curatorial procedures, arrangements to deal with individual complaints and how to handle press queries. Such a policy can be drafted with the help of a lawyer or other arts organisations with experience of exhibiting controversial works.

| STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

We uphold the right of all to experience diverse visions and challenging views that may, at times, offend. We recognise the privilege of living in a country where creating, exhibiting and experiencing such work is protected by fundamental human rights enshrined in UK law. Should controversies arise as a result, we welcome public discussion and debate. We believe such discussion is integral to the experience of the art. But consistent with our fundamental commitment to freedom of expression, we do not censor exhibitions in response to political or ideological pressure. |

Reinforce relations with local authorities and local community groups and routinely discuss the themes of your work with them, why it is important and the kind of education, outreach or debate programmes that will accompany it. Advance preparation should bear in mind the principal legal standard of “reasonableness”. The factors relevant to meeting that standard may include:

- The artistic purposes of an organisation.

- Engagement with the authorities; making early contact will make it easier for them to protect your right to freedom of expression.

- Engagement with the press and individual complaints.

- A willingness to make contingency preparations to manage the risk of any disorder, and subject to the imperative of ensuring that the artistic work is not unduly constrained.

We recommend that you document the decision-making process carefully (see Appendix I). Such a record will be helpful in preparing a response to any police enquiries, and will be useful in responding to protestors and critics, even if no legal action is proposed.

In the case of doubt consider contacting a lawyer with relevant expertise. If you are contacted by the police with regard to a particular work, project or programme, contact a lawyer.

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”94436″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

Questions and answers

Q. What is the difference between Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 19 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights?

A. Freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning considerations regarding its protection must be balanced against other rights and interests. Article 19 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which also addresses freedom of expression, is less qualified: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Nevertheless, even within the UN Declaration there are provisions that contemplate some qualification of the freedom expressed in Article 19. It is the European Convention on Human Rights that is currently relevant to UK law.

Q. Can I challenge a decision by a local authority or police body?

A. Yes. The usual way of doing so would be via judicial review. You should seek specialist legal advice before bringing your claim. Be aware that you must bring your claim as soon as possible and in any event no later than three months after the decision you are challenging. Judicial review is not ordinarily an effective means of quickly overturning decisions. Claims may take many months to be heard. However, it is possible to apply for a claim to be heard quickly if there are good grounds to do so. Even if you succeed you will not usually recover damages: they are awarded at the court’s discretion. The court might quash the decision under challenge, and/or require the public authority to adopt a different procedure in its decision-making.

Q. What is meant by “threatening, insulting or abusive”?

A. The expression “threatening, insulting or abusive” is not defined by the legislation. The courts say instead that the words must be given their “ordinary natural meaning”. Recent amendments to the law have removed the word “insulting” from the definition of the offence under Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986 to enhance the protection of Article 10 rights. Words or behaviour, signs or messages that are merely “insulting”, within hearing range of someone likely to be caused “harassment, alarm or distress”, no longer constitute a criminal offence under Sections 5(1) or 6(4) of the Public Order Act 1986. But more serious, planned and malicious insulting behaviour could still constitute an offence under section 4A. The use of “insulting” words or behaviour still amounts to an offence under section 4 of the Act (fear or provocation of violence). The CPS further notes that in the majority of cases, prosecutors are likely to find that behaviour that can be described as “insulting” can also be described as “abusive”.

Q. What are the legal definitions of racial hatred and racial group?

A. “Racial hatred” is defined in Section 17 of the Public Order Act 1986 as “hatred against a group of people defined by reference to skin colour, race, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origins”. The definition of “racial group” for the purposes of “racially aggravated” public order offences (Section 28 Crime and Disorder Act 1998) mirrors the description of the group of people against whom hatred must be directed for it to amount to “racial hatred” under Section 17 of the Public Order Act 1986. It covers hatred against people of a particular skin colour (e.g. Asian, black, white) a particular nationality or national origin (e.g. French, Israeli, Chinese) or a particular ethnic origin (e.g. Romani, Jews, Sikhs). In the case of racially aggravated public order offences, the courts have stated that a non-technical approach should be taken to the scope of the term “racial group”. Hostility towards persons because of their nationality or what they are (e.g. “bloody Spaniards”) is covered but so is hostility based upon nationality, national origin or citizenship to which a group of persons does not belong (e.g. “bloody foreigners”) (See R v Rogers [2007]). In this sense word “immigrant” is capable of falling within the definition of racial group. Stirring up hatred against refugees, immigrants and asylum seekers will fall foul of the racial hatred provisions. Similarly, demonstrating or being motivated by hostility to members of these groups around the time of committing certain offences will make them racially aggravated offences. The expression “racial group” has over the years been ascribed a particular legal meaning in legislation designed to prohibit race discrimination. To determine where the term falls in relation to criminal or other courts, it is suggested that regard must now be made to Section 9(1) of the Equality Act 2010, which states that “race” includes:

- Colour

- Nationality

- Ethnic or national origins

In relation to the protected characteristic of race:

- A reference to a person who has a particular protected characteristic is a reference to a person of a particular racial group.

- A reference to persons who share a protected characteristic is a reference to persons of the same racial group.

- A racial group is a group of persons defined by reference to race; and a reference to a person’s racial group is a reference to a racial group into which the person falls.

The fact that a racial group comprises two or more distinct racial groups does not prevent it from constituting a particular racial group.

Q. Does “artistic merit” impact the extent to which an artist’s freedom of expression will be protected?

A. It is more likely that a gallery, artist or theatre will be permitted to present controversial works if they are well known and if it is generally considered to have artistic merit. Most police officers are not readily able to assess or appreciate artistic merit or nuance in the context of potential hate crimes. It would therefore be helpful to contact officers with the relevant expertise such as the Art and Antiques or the Community Safety units of the London Metropolitan Police Service. A gratuitous insult is more likely to fall foul of the criminal law than a genuine attempt to express an opinion on a matter of public interest.

Q. Is there a right not to be offended?

A. Under UK law there is no legal right not to be offended. The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly stated that the right to freedom of expression includes the right to shock, disturb and offend.

Q. Is there a blasphemy law in this country?

A. No. The Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 abolished the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel in England and Wales. Blasphemy laws continue to exist in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Q. Is there a difference in law between criticising a belief and criticising a believer?

A. There is no clear distinction in law between criticising a belief and criticising a believer. The intentional use of threatening words to stir up religious hatred is unlawful whether the words are about a general belief system, a particular religious institution, a group of followers or an individual believer. In each case the critical question is whether the words are (a) threatening, and (b) intended to stir up religious hatred. However, it may sometimes be harder to characterise an attack on an abstract religious belief as “threatening” (i.e. menacing or intimidating) than a direct attack on identified individuals.

Q. Do I have to give the script of a play to an authority prior to its opening, if requested?

A. You only have to provide a copy of a script (or any document or property) if the police or local authority have a legal power to view and seize that material. Under Section 10 of the Theatres Act 1968, if a senior police officer has reasonable grounds for suspecting that a performance of a play is likely to involve stirring up racial or religious hatred then he may make an order in relation to that play. An order under that section empowers any police officer to require the person named in the order to produce a script of the play and to allow the officer to make a copy of it.

If a local authority or the police ask to see particular artistic material you should ask them to clarify whether they are demanding that you hand over the material, or whether they are simply asking for your voluntary co-operation. If they are demanding that you provide the material, ask them to identify the legal power that gives them the right to do this and ask to see a copy of any order made under the Theatres Act 1968. You should make a contemporaneous note of their answers. If the police are simply seeking your voluntary co-operation then you do not have to give them anything. If in doubt about the scope of their powers, consult a specialist lawyer.

Q. Does it make any difference if the artist is a member of the same religious or racial group as those who may be offended?

A. The racial or religious identity of the artist is irrelevant to the question of criminal liability. In practice, however, it may be easier for an artist who is a member of the same religious or racial group as the target of their art to persuade a court that their art is not intended to stir up hatred against that group.

Q. Does it make any difference if the perceived attack is directed at an individual?

A. In some cases, the fact that an attack is directed against an identifiable individual may make it more likely that the attack will be construed as abusive or insulting (in the case of racial hatred) or threatening (in the case of racial and religious hatred). On the other hand, the fact it is focused on a particular individual may make it harder to establish it is likely or intended to stir up hatred against a broader racial or religious group. However, each case will turn on its own facts and there is no hard and fast distinction between attacks on individuals and attacks on groups.

Q. Is the right to freedom of artistic expression equal to the right to protest if both are carried out legally?

A. The right to freedom of expression is protected in the European Convention on Human Rights and by UK case law. The right to free assembly is protected as an aspect of this right. Both rights carry great weight, neither automatically outweighs the other and are both qualified rights. This means they may be subject to restrictions where necessary to protect other important interests – for example, protecting national security or the rights of others or preventing crime.

Since protest usually involves the occupation of public space (for example, marches or sit-ins) there are often more countervailing interests (for example, the greater potential for outbursts of violence, the need to protect the safety of passers-by or to keep roads clear for traffic) than with artistic expression.

Q. What potential measures can gallery directors take if the police try to seize artworks?

A. Gallery directors could argue that they have a legitimate reason for distributing, showing or possessing the artistic work, although, as stated above, you should take specialist advice. If you have documented the reasons for exhibiting the work and liaised with the police in advance you will be in a stronger position to ensure that the exhibition or performance can go ahead. If the police insist on seizing artwork, ask them for time to consult a lawyer. Be careful about resisting physically or engaging in a heated debate with police. They could arrest you for obstruction.

Q. What bearing does the Equality Act 2010 have on the arts?

A. The Equality Act 2010 prohibits discrimination because of one or more “protected characteristics”. These are:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion or belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

The conduct prohibited by the Equality Act 2010 is:

- Direct discrimination

- Combined discrimination

- Discrimination arising from disability

- Gender reassignment discrimination: cases of absence from work

- Pregnancy and maternity discrimination

- Indirect discrimination

- Failure to comply with a duty to make reasonable adjustments

- Harassment

- Victimisation

The Equality Act 2010 does not, however, create criminal offences. Breaches of the relevant provisions can only result in declarations or mandatory orders and the award of damages. In certain circumstances, in particular where the respondent is a public authority, public law proceedings may be brought to challenge a discriminatory decision, policy or practice, including in reference to the public sector’s duty to equality.

Artists, theatres, museums and other arts organisations should comply with the Equality Act 2010 to avoid civil suits(6). Further information can be found at the Equality and Human Rights Commission website: http://www. equalityhumanrights.com/private-and-publicsector-guidance

Q. What kind of test would be applied to expression to determine whether or not an artist “intends” to cause an effect proscribed by the criminal law?

A. Intention can be inferred from the conduct or record of the artist under scrutiny and the context in which the work is created. This could cover, among other things, the artist’s previous statements, works, biographical detail, political affiliations, or associations with works or individuals that did not appear to seek to expose or explain racial discrimination but sought instead to promote it.

Appendix 1: Documenting and explaining a decision

Please note: This appendix is for example only and is not a substitute for specialist legal advice tailored to your particular circumstances.

Example: A theatre seeks to show a play that will include satirical images of religious practices, teachings and iconography. The arts organisation decides the work has value but considers that there is a risk that the work could be characterised as threatening and intended to stir up racial or religious hatred. The decision to proceed could be documented as follows:

- The artist’s motivation is to explore the influence of religion on politics and international affairs (for example).

- It responds to a debate of public interest, the role of religion in shaping society’s attitudes towards relationships/sexuality/family/gender or the concept of national identity in a multicultural and increasingly diverse community (for example).

- We have acknowledged the importance of conducting a critical argument about all belief systems and using the arts to stimulate legitimate debate in this case.

- There is public interest in exposing corruption, injustice or malpractice no matter what race or religion the perpetrator.

- There is a public interest in freedom of artistic expression itself and we consider that this is work of value which should be seen in the context of this important public debate.

- The work has artistic merit and the artist has exhibited/sold numerous copies of previous works that have been positively reviewed (provide examples).

- We have considered the context of previous work by the same artist, the role of controversy in the work and provided examples.

- The work forms part of a broader project/ exhibition designed to educate or stimulate discussion on an important issue.

- We recognise that the content is challenging and provocative. In order to prepare the audience we have taken the following steps:

- All audience members are advised, when buying tickets, that the work contains images and plotlines that may offend those of certain religious faiths.

- Similar advice is provided on all promotional material and on the entrance to the building.

- We have carefully considered our own guidance policy with regard to equal rights and representation of racial and religious issues (and/ or the relevant local or other authority).

Footnotes

- At the time of writing (August 2015), the government is considering abolishing the Human Rights Act and introducing a British Bill of Rights. Free expression rights remain protected by UK common law, but it is unclear to what extent more recent developments in the law based on Article 10 would still apply

- See in particular Hare, I, Legislating Against Hate – The Legal Response to Bias Crimes; (1997) 17 OJLS 415

- See also for further reference, Monaghan on Equality Law, 2nd Edition, OUP, 2013

- See http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/archive/law-order/8978

- http://www.equalityni.org/Footer-Links/Legislation

- See also for further reference, Monaghan on Equality Law, 2nd Edition, OUP, 2013

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”5″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500623467104-37bda033-0abd-6″ taxonomies=”8886″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Feb 2016 | Art and the Law, Art and the Law Guides, Campaigns, Index Reports

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This guide is also available as a PDF.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Preface

Freedom of expression is essential to the arts. But the laws and practices that protect and nurture free expression are often poorly understood both by practitioners and by those enforcing the law. The law itself is often contradictory, and even the rights that underpin the laws are fraught with qualifications that can potentially undermine artistic free expression.

As indicated in these packs, and illustrated by the online case studies – available at indexoncensorship. org/artandoffence – there is scope to develop greater understanding of the ways in which artists and arts organisations can navigate the complexity of the law, and when and how to work with the police. We aim to put into context the constraints implicit in the European Convention on Human Rights and so address unnecessary censorship and self-censorship.

Censorship of the arts in the UK results from a wide range of competing interests – public safety and public order, religious sensibilities and corporate interests. All too often these constraints are imposed without clear guidance or legal basis.

These law packs are the result of an earlier study by Index: Taking the Offensive, which showed how self-censorship manifests itself in arts organisations and institutions. The causes of self-censorship ranged from the fear of causing offence, losing financial support, hostile public reaction or media storm, police intervention, prejudice, managing diversity and the impact of risk aversion. Many participants in our study said that a lack of knowledge around legal limits contributed to self-censorship.

These packs are intended to tackle that lack of knowledge. We intend them as “living” documents, to be enhanced and developed in partnership with arts groups so that artistic freedom is nurtured and nourished.

Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive, Index on Censorship

Foreword by Dominic Johnson

Censorship, obscenity and freedom of expression reflect the higher question of what, in a particular time and place, is sayable or unsayable. Not all artists are intent on pushing the boundaries of this problem, but when we do so, our work might appear to others as too intense, too ugly, too beautiful, too crazy, too painful, too long, too weird, too personal, too pleasurable.

By being too much works of art or performance that reinvent the scope of the sayable will inevitably strain at the limits of aesthetic acceptability. The feeling of the work’s proximity might seem akin to being slapped in the face, held by the scruff or punched in the gut. Hence reactions they prompt – from individuals, communities, institutions, the media or the state – may themselves be profoundly physical, visceral and emotional, redoubling the perceived extremity of the initial provocation.

Beyond aesthetic extremity, a controversial work may also contravene other limits, be they cultural, social, political or legal. The effects of such transgressions attach themselves to artists, and may include financial burdens, stress from stigma or ridicule and institutional blacklisting. To avoid such effects, artists may clip their own wings, through anticipatory self-censorship, to inhibit the creative reach of one’s investigations as an artist.

Yet the conviction that an artist must be free to explore the limits of one’s personal and collective possibility can slip into cliché, or obscure the possibility that my freedom may sometimes impinge on the freedoms of others – curtailing, say, a viewer’s right to remain safe from personal discomfort, psychological upset, intolerance or hate, or the supposed dangers of moral turpitude.

As artists and audiences, each of us is intimately aware of one’s own limits. We may feel squeamish before representations of the spilling of blood, open wounds, sex or extremely intimate demonstrations. We might close our eyes or avert our gazes, fall fainting on the floor, intervene somehow, turn vandal or leave. A liberated state of making, showing and seeing art would welcome all our most sensitive, outraged and overwhelmed states: celebrating our sweaty palms, flushes and blushes, increased heartbeat, syncope, fight or flight. The extent to which such states can be provoked, without causing unwarranted harm or hurt or injury, is the test of how far we might go as artists and audiences, into the still-yet-uncharted territories of both the sayable and the unsayable.

Dominic Johnson is Senior Lecturer in Drama at Queen Mary University of London

Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is a UK common law right, and a right enshrined and protected in UK law by the Human Rights Act(1) , which incorporates the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

The most important of the Convention’s protections in this context is Article 10.

ARTICLE 10, EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

- Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent states from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

- The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

|

It is worth noting that freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning the right must be balanced against other rights. Where an artistic work presents ideas that are controversial or shocking, the courts have made it clear that freedom of expression protections still apply.

As Sir Stephen Sedley, a former Court of Appeal judge, explained: “Free speech includes not only the inoffensive but the irritating, the contentious, the eccentric, the heretical, the unwelcome and the provocative provided it does not tend to provoke violence. Freedom only to speak inoffensively is not worth having.” (Redmond-Bate v Director of Public Prosecutions, 1999).

Thus to a certain extent, artists and galleries can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock, disturb and offend.

As is seen above, freedom of expression is not an absolute right and can be limited by other rights and considerations. While the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and police have a positive obligation to promote the right to freedom of expression, they also have a duty to protect other rights: to private and family life, the right to protection of health and morals and the protection of reputation.

Obscene publications offences explained

Obscene publications are governed by the Obscene Publications Act 1959 and the Obscene Publications Act 1964. The 1959 Act sets out the legal test for obscenity and creates certain offences and defences.

Section 1(1) of the Obscene Publications Act (OPA) 1959 describes an “obscene” item as one that has the effect of tending to deprave and corrupt persons likely to read, see or hear it. This statutory definition is largely based on the common law test of obscenity, as laid down in the case of R. v Hicklin (1868) L.R. 3 Q.B. 360, namely:

| “whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.” |

In cases such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover [R. v Penguin Books Ltd (1961)] and the prosecution of the publishers of Last Exit to Brooklyn [R. v Calder and Boyars Ltd (1969)] the courts have defined “deprave” as meaning to make morally bad, to debase, to pervert, or corrupt morally, and “corrupt” as meaning to render morally unsound or rotten, to destroy moral purity or chastity, to pervert or ruin a good quality, and to debase or defile.

An item covered by the OPA is referred to as an “article”. Section 1(2) broadly defines an article to include works that can be read or looked at, including recordings, films and pictures (including negatives of pictures, under Section 2(1) of the OPA 1964).

The nature of material that can be held to be obscene is not limited to material of a sexual nature. In fact, it has been held by the courts that material glamourising, or inducing, potentially dangerous behaviour, such as drug taking, may amount to an “obscene” publication [Calder (Publications) Ltd v Powell [1965]].

The intended viewer or recipient can be a specific individual or a group.

The Theatres Act 1968 applies a similar definition of obscenity to plays and performances. Section 162(1) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 extends the concept of “publication” under the OPA 1959 to include live programme material.