15 Jan 2014 | China, Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Despite state censorship and political repression, social media is changing the protest landscape in China.

With the exception of economic reform that started in the late 1970’s, the country has remained restricted by government policy and ideology. A one party state has led to a national media that lacks plurality and regularly fails to report on incidents that they fear may damage the government’s image. Combined with internet censoring and heavy-handed tactics being employed against state opposition, freedom of expression has always been limited, but there is hope for change.

Social media within China has expanded rapidly, Sina Weibo — 60 million active daily users, 600 million registered users (Sep 2013) — and WeChat — 300 million registered users, of which 100 million are international (Aug 2013) — are two of the most popular. This allows a democratic spread of information that has never previously been available to citizen journalists or local people.

A media project by the University of Hong Kong showed the importance of Weibo in relation to the 2012 protest in Shifang against potential environmental damage by a proposed copper plant. Traditional media largely declined to report on the protests themselves, but made reference to ‘an incident’ and the rising stock price of a tear gas company, whose product was used on protestors. In contrast, there were around 5.25 million posts on Weibo containing the term ‘Shifang’ between 1-4 July with 400,000 containing images and 10,000 containing video. A similar incident occurred in Chengdu, Sichuan province, when factory workers went on strike to demand higher wages. State media ignored the protests while social media spread the news that tear gas was being used, along with images of the protest. Eventually officials stepped down and workers received a raise. Physical protests can be complemented by online activity, but it is not without difficulties.

In addition to the notorious firewall, the government can censor specific words to try and control the narrative of any given incident, by pushing their own agenda and restricting citizens’ freedom of expression. However, many online users use images, and memes in particular can portray a serious topic in a light-hearted manner, further increasing the spread of information.

An OECD report in 2013 evaluated government trust in various countries, China ranked very well with 66% compared to an OECD country average of 40%. However, this disguises some of the ill-feeling towards local government officials, who are usually held accountable by the people. This could change though, as economic policy, typically the role of central government, leads to growing inequality. New leadership within the government is attempting to maintain and improve government trust, by introducing ‘Mao-esque’ techniques in an attempt to bring everyone together under one nation.

It is clear that censorship is one way of trying to achieve this, as those who openly promote citizens’ rights, inclusive democracy and transparency are regularly arrested, including Xu Zhiyong. Additionally, new training materials for journalists and editors suggest a government eager to maintain control, as they expect that the media “must be loyal to the party, adhere to the party’s leadership and make the principle of loyalty to the party the principle of journalistic profession.”

Recently, a planned protest to honour a strike over censorship last year was pre-emptively halted, when police warned or detained several people thought to be involved. A well-known campaigner for freedom of expression, Wu Wei, said that protests such as this were not accepted by the government, as they did not fit “within their social stability framework.”

The government is so concerned over social instability that Tiananmen Square is heavily monitored by uniformed and plain-clothed police. The ability to suppress dissent as quickly as possible is necessary in a popular tourist destination, to portray the image of a peaceful China to both international and domestic visitors. The digital censorship employed the government is reflected in physical terms by the large security presence in one of China’s most well-known but contentious landmarks.

The Chinese government is keen to have control over the nation’s information, and fear that freedom of expression and information could pose a threat to their power. Social media offers a critical viewpoint that is lacking from state-controlled media. However, even social media has not been able to completely detach itself from the Chinese government’s censorship.

Nonetheless, the increasing use of social media and rapid spread of information is putting pressure on the government that it has never felt before while the digital revolution is gaining more and more momentum. Democratic consciousness is rising in China and with the state pursuing an oppressive agenda, cultural change from the bottom-up, rather than institutionalised change from the top-down, is necessary to pursue these principles.

This article was posted on 15 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society

Activists are continually harassed and punished for standing up and speaking out about social and political issues they feel are unjust in their country. Here are five activists whose government didn’t quite like what they had to say.

Raif Badawi- Saudi blogger punished after calling for ‘day of liberalism’

It would seem absurd to most people that “liking” a Facebook page could land you in jail. However, that was one of the crimes charged against Raif Badawi after he “liked” an Arab Christian page on the social networking site. The young co-founder of the Liberal Saudi Network, a website that has since been shut down, was arrested in June 2012 for “insulting Islam through electronic channels”, including insulting Islam and portraying disobedience.

In January, a court had refused to hear apostasy charges against Badawi, concluding that there was no case. Apostasy carries the death sentence in Saudi Arabia. He has since been sentenced to 600 lashes and seven years in jail.

Eskinder Nega- Ethiopian blogger

Eskinder Nega is a well-known name in Ethiopia whose journalism has been recognised by major organisations globally; he is currently serving 18 years in jail for supposedly violating the country’s anti-terrorism legislation.

Nega was arrested in September 2011 after publishing, somewhat ironically, an article criticising his government’s detainment of journalists as suspected terrorists, in particular the arrest of Ethiopian actor and government critic Debebe Eshetu . Along with 23 others, he was then convicted of having links with US-based opposition group Ginbot Seven, an organisation Ethiopia had recently added to its list of terrorists.

This is not the first time Nega has been imprisoned for speaking out in defense human rights. Meles Zenawi’s government handed him a total of eight sentences over the past decade. He is also not the only journalist to face prosecution under the Ethiopian government. According to the Amnesty Annual Report 2013 a number of journalists and political opposition members were sentenced to lengthy prison terms on terrorism charges for calling for reform, criticizing the government, or for links with peaceful protest movements. Much of the evidence used against these individuals consisted of examples of them exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association.

Shi Tao- Stung by Yahoo in China

2013 was a good year for Shi Tao; the Chinese reporter was finally released after documents leaked by Yahoo to his government saw him spend the past eight and a half years behind bars.

Tao sent details of a government memo about restrictions on news coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre anniversary to a human rights forum in the United States. He was subsequently arrested in 2004 and sentenced the following year charged with disclosing state secrets.

Reporters Without Borders said the branch of Yahoo in Hong Kong assisted the Chinese government in linking Shi Tao’s email account to the message containing the information he had sent abroad. Yahoo was heavily criticised at the time by human rights activists and U.S. legislators with Jerry Yang, co-founder of Yahoo, publicly apologising to Shi Tao’s family.

Tao was released 15 months before the end of us 10 year restriction. It is unclear why his early release occurred.

Ngo Hao- Vietnamese blogger

You’re never too old to go to prison as 65-year-old activist Ngo Hao found out after he was handed 15 year sentence earlier this year on charges of attempting to overthrow the Vietnamese government. Accused of writing and circulating false and defamatory information about his government and its leaders, Hao was arrested in February. Further accusations included a peaceful attempt to instil an Arab Spring-style revolution and of working with dissident group Bloc 8406.

Reporters Without Borders criticised Hao’s trial for a lack of his right to a fair defence and the unwillingness to allow any family members to attend the hearing asides from his son.

Just weeks before an appeal court in the south of the country also sentenced two bloggers, Nguyen Phuong Uyen and Dinh Nguyen Kha. This takes the estimated total of bloggers behind bars in Vietnam to 36.

Jabeur Mejri- Tunisian blogger seven and a half years for posting on Facebook

After the 2011 Arab Spring many Tunisian bloggers were able to express themselves freely; a stark contrast to the censorship, arrest and jail they had come to expect under the rule of former President Ben Ali. One such blogger was Jabeur Mejri who, in March 2012, posted a cartoon of the Prophet Mohamed on his Facebook page, a post that sentenced the blogger to over seven years in jail for “attacking sacred values through actions or words” and “undermining public morals”.

The rise of ‘opinion trials’ has become a concern to many with Mejri being the first person sent to jail under the procedure. Lina Ben Mhenni told Amnesty International: “You can go to jail for a word or an idea. ‘Opinion trials’ have become part of our daily lives. As in many other countries, Tunisia’s taboo topics are religion and politics. You can’t criticize the government in general or the Islamists in particular.”

19 Dec 2013 | China, News and features, South Africa

The City of Cape Town launched the Nelson Mandela Legacy Exhibition to honour his contribution to South Africa’s democracy. The exhibiton is a collection of historic photographs and visuals capturing significant moments in Mandela’s life. (Photo: Sumaya Hisham / Demotix)

Chinese coverage of Nelson Mandela’s death has reflected the government’s new-found sympathy for Maoism, its rejection of democracy and its long-standing sensitivities over Tibet and Taiwan.

When Nelson Mandela died, the official statement from President Xi Jinping praised Mandela as “an accomplished politician of global standing,” while state-owned China Central Television described him as “an old friend of China”.

This was to be a precursor for the following day’s censorship — which banned coverage referencing “freedom”,“democracy”, Mandela’s Nobel Peace Prize and foreign policy hot topics Tibet and Taiwan.

While President Xi Jinping did not attend Mandela’s funeral himself, his Vice President Li Yunchao did, and was booed by crowds as he made his memorial speech.

Xi commented on Mandela’s bright smile, called him a “towering figure” and “an old friend of China”. There was no mention of “freedom” or “democracy”.

In an op-ed for CNN, deputy director of Asia division for Human Rights Watch Phelim Kene argued that the deliberate omissions in official statements, as well as the selective censorship policy, was a ploy to distract attention away from China’s own Nobel Peace Prize-winning freedom and democracy activist, Liu Xiaobo.

In 2009, democracy activist Liu was charged with inciting subversion and sentenced to 11 years in prison. His name has since been banned from Chinese micro-blogging sites, although the state-owned Chinese newspaper Global Times broke the ban recently to issue a seething counter-West editorial, accusing American editors of falsely painting Liu as “China’s Mandela”.

According to The Global Times, outlets like The Washington Post, New York Times and CNN had deliberately focused on the imprisonment of Liu in an attempt to foster unrest.

An op-ed argued that “Mandela was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for leading African people to anti-apartheid victory through struggle, tolerance and efforts to bridge differences,” while Liu had “confronted authorities” and “was dealt with under strict legal procedures. This system ensures that a society of 1.3 billion people runs smoothly.” The piece also argued that “mainstream Chinese society” had rejected Liu’s campaign for democracy.

Yet the circumstances of two men’s imprisonment remain remarkably similar. Mandela was charged and sentenced after he helped produce South Africa’s pro-democracy “Freedom Charter”. Liu, similarly, is one of the activists who drafted “Charter ‘08”, a manifesto for Chinese democracy. Families of both men were persecuted by the state and censorship departments in both countries attempted to remove all mention of the dissenters from the media (including previously written works).

Promotion of Mao’s legacy seems to be Xi Jinping’s communications strategy of choice — and it appears Mandela’s death has been co-opted into this “Maoisation” of Chinese politics. State press releases asserted that Mandela had read Mao’s “Little Red Book” while imprisoned on Robben Island, as well as describing himself as a “student of Mao”.

Mandela was certainly a fan of Mao, though principally for his military strategies rather than his later domestic policies. In a TIME Magazine interview, he praised the tactics used during the “Long March”, as well as his “determination and non-traditional thinking,” which Mandela briefly noted in his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom.

Overall, the Chinese press complied with censorship restrictions to censor the words “freedom” and “democracy” from accounts of Mandela’s life and death, as well as steering clear of Tibet and Taiwan, both contentious foreign policy issues that Mandela had previously weighed in on. Under his presidency, South Africa cut off ties with Taiwan over its previous support for Apartheid, and in favour of Communist mainland China.

Mandela had also met with the Dalai Lama on several occasions, who issued a video tribute to Mandela. The Tibetan leader has been refused a visa to visit South Africa twice in the last four years, regarded by many as an attempt not to risk diplomatic relations with China.

A dictat from China’s Foreign Ministry also attempted to censor “posts and comments on Weibo that take advantage of Mandela’s funeral to attack our political system and state leaders”, ordering offending content to be deleted immediately.

Property tycoon Ren Zhiqiang commented on Weibo: “Because he was a fighter — for all his life— for democracy, equality and peace and harmony, he is now an icon of all these.” Another user, from Shanxi, wrote “A great leader, rest in peace.”

Some Weibo users employed sarcasm to express their views. In response to philanthropist Fan Wei asking “Will China have its own Mandela?” one user replied, “Heroes only appear in turbulent times. In our ‘harmonious’ homeland, there is no use for Mandelas.” Another simply said, “They are in prison.”

“Old friend?” another user mocked. “He pursued justice, fairness and freedom. Does he have anything to do with you? Don’t blow your own trumpet.”

Notably, the so-called “New Left” Maoists reacted hotly to the government’s comparisons, with Weibo messages strongly in favour of Mao Zedong over Mandela.

“India’s Gandhi and South Africa’s Mandela were great. But Chairman Mao surpassed them all,” said one.

Another commented, “Mandela had bowed to racism. His consideration of the Tibetan independence movement as a human rights movement was a big, big mistake. He is a banana with dark skin.”

The death of Mandela has also resurrected an unlikely pop song from the 1990s. The Hong Kong-based band Beyond surged back into the charts with their song “Glorious Days”, reaching number one after almost a decade of hiatus.

“Glorious Days” had already achieved chart success in the post-Tiananmen era, when many were afraid to discuss political issues. Released in the midst of a music scene that mainly comprised of love songs, the Cantonese pop band achieved record sales with a song about racial equality, which was dedicated to Nelson Mandela.

This article was published on 19 Dec, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Nov 2013 | Africa, News and features

1) Angola

Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves was held in solitary confinement for printing t-shirts. Image from his Facebook page.

Angolan 17-year-old Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves went on hunger strike on Tuesday, following his arrest on 12 September for printing t-shirts with the slogan “Out Disgusting Dictator”. The message was aimed at the country’s President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has held power in since 1979. The shirts were to be worn at a demonstration in the capital Luanda, highlighting corruption, forced evictions, police violence and lack of social justice under dos Santos’ regime. Nito Alves has been charged with “insulting the president”, and has now spent almost two months in detention – parts of it in solitary confinement. His family were barred from seeing him, and three weeks went by before he was allowed to speak to a lawyer. The hunger strike is in protest at his “unjust and inhumane treatment”.

2) Belarus

Yury Rubstow wearing the t-shirt that landed him in prison. (Image Viasna Human

Rights Centre)

On Monday, Belarusian opposition activist Yury Rubstow was sentenced to three days in jail for wearing a t-shirt with the slogan “Lukashenko, go away” on the front, and “A four-time president? No. This is not a president but an impostor tsar” on the back.” The message was aimed at the country’s dictator Alexander Lukashenko, during an opposition protest march. He was found guilty of disobedience to police officers under Article 23.4 of the Civil Offenses Code.

3) Swaziland

In 2010, Sipho Jele, a member of Swaziland’s People’s United Democratic Movement, was arrested for wearing a t-shirt supporting the party during a May Day parade. He was arrested under the country’s Suppression of Terrorism Act, and died in custody. The police said he had hanged himself, while the party say the police of killed him.

4) Egypt

The Rabaa symbol displayed at a protest in Turkey (Image Bünyamin Salman/Demotix)

In September, three Egyptian men were arrested for wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the Rabaa symbol. A hand holding up four fingers, it is widely used by those opposing Egypt’s interim military-backed government, and the coup that ushered in in. Mohamed Youssef, the country’s kung fu champion, was also suspended by the national federation for wearing a similar t-shirt during a medal ceremony.

5) Hong Kong

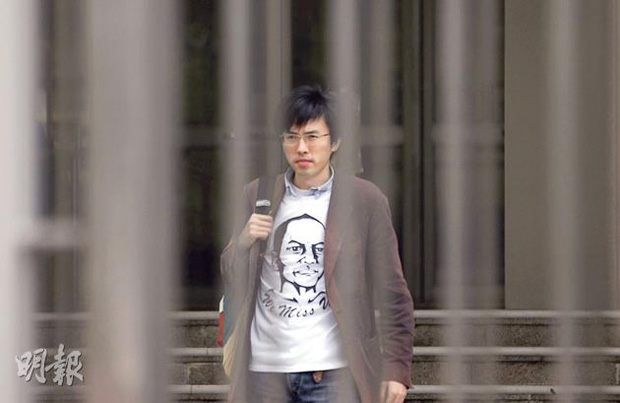

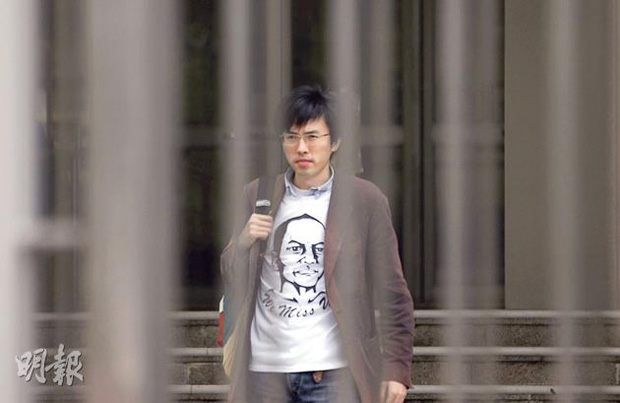

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

An activist from Hong Kong was arrested last December for throwing a t-shirt at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit almost six month earlier, on 1 July. League of Social Democrats Vice Chairman Avery Ng threw a t-shirt with a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang, a Tiananmen Square activist who died under suspicious circumstances only weeks before the visit. Ng was charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place”.

6) Malaysia

Malaysian protester wearing a Bersih shirt. (Image Syahrin Abdul Aziz/Demotix)

In June 2011, Malaysian police arrested 14 opposition activists for wearing t-shirts promoting a rally in Kuala Lumpur calling for election reform. The shirts carried the slogan “bersih” which means “clean”, and is the name of one of the groups behind the protest. Authorities claimed the demonstration was an “attempt to create chaos on the streets and undermine the government”, and they were therefore within their rights to arrest the protesters. They also confiscated t-shirts from the group’s headquarters.

7 & 8) The US

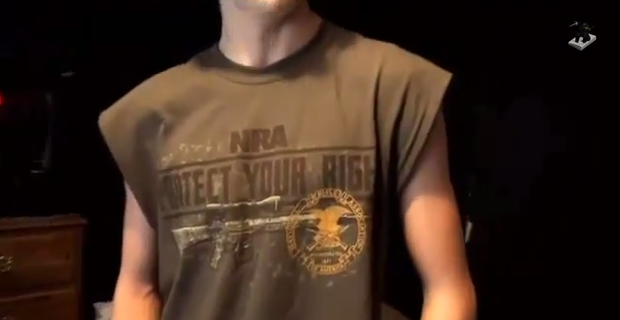

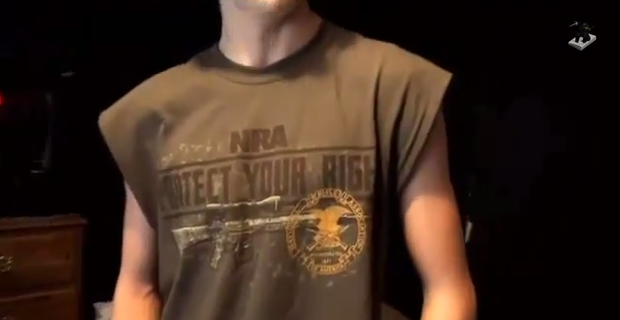

Jared Marcum wearing his NRA t-shirt in a TV report. (Image Youtube)

A 14-year-old student from West Virginia was in April suspended from school and subsequently arrested for refusing to remove a t-shirt supporting the pro-gun National Rifle Association. Jared Marcum was charged with “obstructing an officer” and faced a $500 fine and up to one year in prison.

On the flip side, a Tennessee man was arrested for wearing a t-shirt in support of stricter gun control laws. Stanley Bryce Myszka was wearing a shirt that read “Has your gun killed a kindergartener today?” at a shopping centre, following the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. He was approached by security guards, who called the police when he when he refused to remove the shirt. He was also banned from the shopping centre for life.

9) United Kingdom

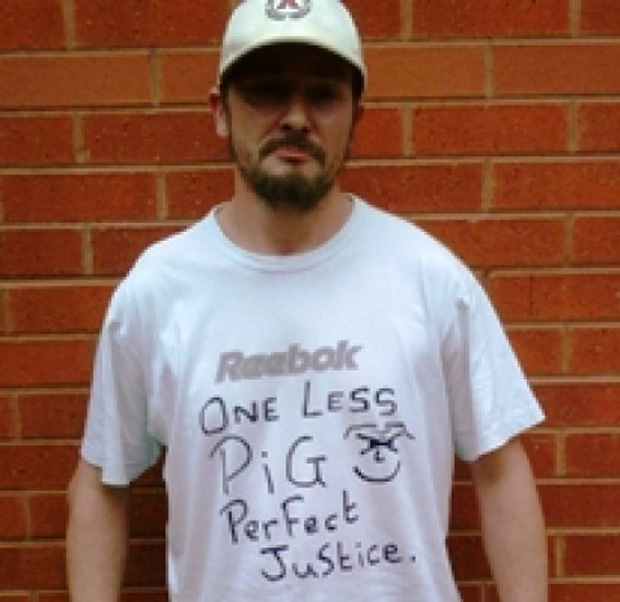

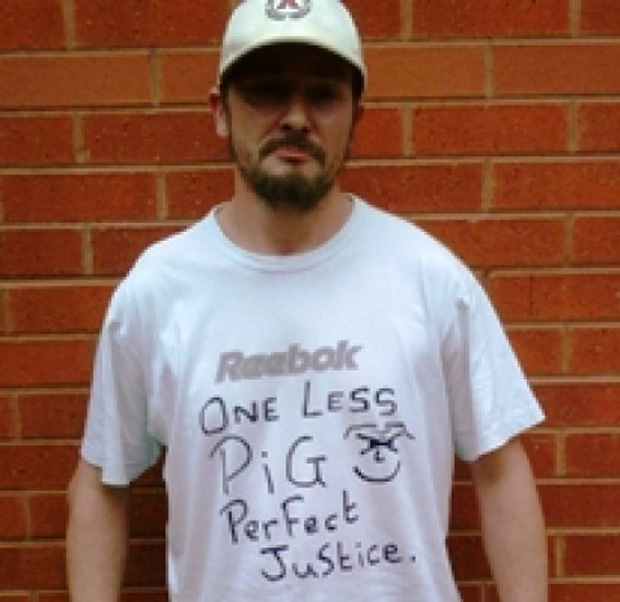

The front of Barry Thew’s t-shirt. (Image Greater Manchester Police)

A Manchester man was in October 2012 sentenced to eight months in prison in part for wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with offensive comments referencing the murders of two policewomen. Barry Thew had written “One less pig; perfect justice” on the front of his t-shirt and “killacopforfun.com haha” on the back. While four months of the sentence was handed down for breach of a previous suspended sentence, he was charged on a Section 4A Public Order Offence for the t-shirt incident.