31 Mar 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“I wear my Turkish and Muslim identity as easily a pair of well-worn jeans. I no longer worry that my writing will land me in trouble.”

These were some of the heady feelings I shared with Yeni Safak, a highbrow pro-Islamic newspaper, in a 2005 interview. Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) had been in power for just three years. Overtly pious yet savvily flexible AKP used its big popular mandate to dismantle decades of army tutelage and embark on a giddying raft of reforms. Turkey, it seemed, was on a path to full-blooded democracy, shaming the European Union into opening talks for Turkish membership that same year.

It was a golden age. Erdogan became the first leader to publicly acknowledge that the country’s long-suffering Kurds had been treated unfairly by the state. Bans on the Kurdish language were steadily eased while Kurdish rebel leaders sat opposite Turkish government officials to hammer out a deal for lasting peace.

The changes swept across the ethnic, religious and ideological divide. Using the word genocide which accurately captures the horrors that befell the Ottoman Armenians in 1915 was no longer a criminal offence. In 2003, Turkey’s long-suppressed yet vibrant LGBT community held its first ever gay pride march in Istanbul. In 2011, Zenne, a film about the first officially recorded gay honour killing in Turkey, swept five of the country’s prestigious Antalya Golden Orange awards including best film. That night as I snuggled in bed with my beloved friends and the film’s co-directors, Caner Alper and Mehmet Binay, my heart soared. Albeit in fits and starts, my country was becoming a community of shared values, where citizens of all stripes and creeds could find a place for themselves, be respected, and treated equally before the law. And yes, a majority Muslim country that could prove to hundreds of millions of other Muslims living under thuggish regimes that yes, it is possible, that yes, they too can become us, this. Or so I believed.

Six years on it all seems like a distant dream.

Today, Yeni Safak, is nothing but a government propaganda sheet, spouting off obscene conspiracy theories about how everything from the failed July 2016 coup attempt, to the deadly New Year’s Eve shooting spree at the Reina nightclub in Istanbul, were all engineered by the USA, and other dark forces bent on destroying Turkey.

Apparently I was among them. Turgay Guler, the managing editor of another pro-government title, Gunes, said I helped “plan” the Reina attack. He declared this to his 480 thousand plus Twitter followers unleashing a tidal wave of cyber threats which inundated my timeline for days. The tweet has not been removed. A Turkish prosecutor saw no harm in it and ignored my formal complaint, as has Twitter. Yet, well over a hundred of my colleagues, some of them dear, trusted friends, are languishing in jail for airing critical views of the government that are grounded in hard facts.

Peace with the Kurds is also on thin ice. A two and a half year-long ceasefire with the Kurdish rebels broke down in July 2015, soon after Mr Erdogan disowned a draft roadmap for peace that was initiated between his government and Kurdish leaders. The rebels recklessly threw coals on the fire by carrying the battle into towns and cities. Over 2,000 people, at least 300 of them are thought to be civilians, have died in the fighting since then

Emboldened by the new spirit of openness Diyarbakir, the biggest and most vibrant city in the mainly Kurdish south-east region had been striving to recreate its multi-cultural past. Udi Yervant, a renowned Armenian oud virtuoso gave up his life in California to return. Today, Diyarbakir is a ghost of its former self. Large chunks of its historic centre, home to a glorious Armenian Orthodox church, and a cherished Ottoman mosque, were pulverised following months of bitter fighting between Kurdish rebel youths and Turkish security forces, who bloodily prevailed. Diyarbakir’s co-mayors, a man and a woman, in keeping with the main Kurdish parties’ emphasis on gender equality, are currently in prison on thinly-supported terror charges.

Tens of thousands of others have been sacked, jailed or both, on tenuous charges of involvement in the failed putsch. Fethullah Gulen, the Sunni cleric and a former ally of Erdogan is accused of masterminding the coup. While there is little doubt that many of his associates were involved few believe they were acting alone.

Torture and arbitrary detentions are once again the norm. Not since the 1980 coup has Turkey been this divided, broken and grim. Should yes votes outnumber the nos in a critical referendum on formalising the vast powers Erdogan already exercises, Turkey’s sharp turn towards authoritarianism can only accelerate. And in the opposite case a fresh cycle of revenge may be on the cards.

How did it come to this? Many say it is because Erdogan was never serious about democracy. His real goal all along was to supplant the generals’ tutelage with his own. Others blame Turkey’s perennially squabbling pro-secular opposition politicians.

Power crazed Gulen has caused incalculable harm as well. Then there is Europe which held out the hope of full membership only for the likes of Germany’s Angela Merkel and the former French president, Nicholas Sarkozy to declare that it was all a farce. Turkey was too big, too Muslim and too poor. Either way, the rise of populism and xenophobic nationalism infecting Turkey is a global trend.

Many cast the April 16 referendum as a final chance to turn back the clock. But the odds are heavily stacked against the opposition. The referendum is being held under emergency rule. The government has virtually full control of the media. It is painting the vote as a choice between Erdogan and the abyss, between patriotism and treachery. Whatever the outcome, Turkey has entered uncharted waters. The big question now is how long it can remain afloat.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490975695361-635cda74-947b-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Mar 2017 | media freedom featured, News and features

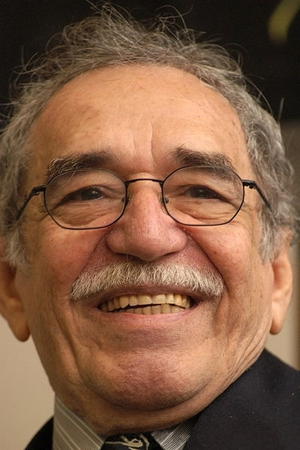

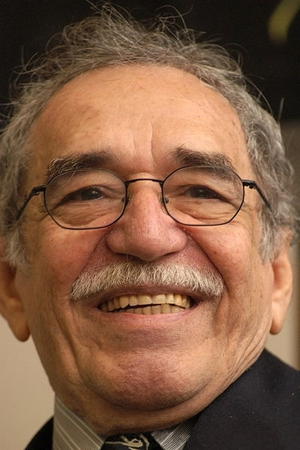

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”This is the third in a series of articles exploring media freedom drawn from the archives of Index on Censorship magazine. Writing in 1997, the late Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez discussed the evolution of journalism. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control“ ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

The newspaper was then divided into three large departments: news, features and editorial. The most prestigious and sensitive was the editorial department; a reporter was at the bottom of the heap, somewhere between an intern and a gopher. Time and the profession itself has proved that the nerve centre of journalism functions the other way. At the age of 19 I began a career as an editorial writer and slowly climbed the career ladder through hard work to the top position of cub reporter.

Then came schools of journalism and the arrival of technology. The graduates from the former arrived with little knowledge of grammar and syntax, difficulty in understanding concepts of any complexity and a dangerous misunderstanding of the profession in which the importance of a “scoop” at any price overrode all ethical considerations.

The profession, it seems, did not evolve as quickly as its instruments of work. Journalists were lost in a labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control. In other words: the newspaper business has involved itself in furious competition for material modernisation, leaving behind the training of its foot soldiers, the reporters, and abandoning the old mechanisms of participation that strengthened the professional spirit. Newsrooms have become a sceptic laboratories for solitary travellers, where it seems easier to communicate with extraterrestrial phenomena than with readers’ hearts. The dehumanisation is galloping.

Before the teletype and the telex were invented, a man with a vocation for martyrdom would monitor the radio, capturing from the air the news of the world from what seemed little more than extraterrestrial whistles. A well-informed writer would piece the fragments together, adding background and other relevant details as if reconstructing the skeleton of a dinosaur from a single vertebra. Only editorialising was forbidden, because that was the sacred right of the newspaper’s publisher, whose editorials, everyone assumed, were written by him, even if they weren’t, and were always written in impenetrable and labyrinthine prose, which, so history relates, were then unravelled by the publisher’s personal typesetter often hired for that express purpose.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1490025191055{background-color: #dd3333 !important;}” el_class=”text_white”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protect Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fdefend-media-freedom-donate-index%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

Reporters working to share the truth are being harassed, intimidated and prosecuted – across the globe.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490025163341{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/newspapers.jpg?id=50885) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Today fact and opinion have become entangled: there is comment in news reporting; the editorial is enriched with facts. The end product is none the better for it and never before has the profession been more dangerous. Unwitting or deliberate mistakes, malign manipulations and poisonous distortions can turn a news item into a dangerous weapon.

Quotes from “informed sources” or “government officials” who ask to remain anonymous, or by observers who know everything and whom nobody knows, cover up all manner of violations that go unpunished.But the guilty party holds on to his right not to reveal his source, without asking himself whether he is a gullible tool of the source,manipulated into passing on the information in the form chosen by his source. I believe bad journalists cherish their source as their own life – especially if it is an official source – endow it with a mythical quality, protect it, nurture it and ultimately develop a dangerous complicity with it that leads them to reject the need for a second source.

At the risk of becoming anecdotal, I believe that another guilty party in this drama is the tape recorder. Before it was invented, the job was done well with only three elements of work: the notebook, foolproof ethics and a pair of ears with which we reporters listened to what the sources were telling us. The professional and ethical manual for the tape recorder has not been invented yet. Somebody needs to teach young reporters that the recorder is not a substitute for the memory, but a simple evolved version of the serviceable, old-fashioned notebook.

The tape recorder listens, repeats – like a digital parrot – but it does not think; it is loyal, but it does not have a heart; and, in the end, the literal version it will have captured will never be as trustworthy as that kept by the journalist who pays attention to the real words of the interlocutor and, at the same time, evaluates and qualifies them from his knowledge and experience.

The tape recorder is entirely to blame for the undue importance now attached to the interview. Given the nature of radio and television, it is only to be expected that it became their mainstay. Now even the print media seems to share the erroneous idea that the voice of truth is not that of the journalist but of the interviewee. Maybe the solution is to return to the lowly little notebook so the journalist can edit intelligently as he listens, and relegate the tape recorder to its real role as invaluable witness.

It is some comfort to believe that ethical transgressions and other problems that degrade and embarrass today’s journalism are not always the result of immorality, but also stem from the lack of professional skill. Perhaps the misfortune of schools of journalism is that while they do teach some useful tricks of the trade, they teach little about the profession itself. Any training in schools of journalism must be based on three fundamental principles: first and foremost, there must be aptitude and talent; then the knowledge that “investigative” journalism is not something special, but that all journalism must, by definition, be investigative; and, third, the awareness that ethics are not merely an occasional condition of the trade, but an integral part, as essentially a part of each other as the buzz and the horsefly.

The final objective of any journalism school should, nevertheless, be to return to basic training on the job and to restore journalism to its original public service function; to reinvent those passionate daily 5pm informal coffee-break seminars of the old newspaper office.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490029034441-d7ddf233-4a8c-3″ taxonomies=”9044″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80569″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Mar 2017 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Five journalists were detained in Orsha on 12 March after covering a protest against a new law that would tax unemployed people labeled as “parasites”, Radio Svaboda reported.

Radio Svaboda’s Halina Abakunchyk, photographer for BelaPAN Andrei Shaulyuha and blogger Anastasia Pilyuhina were detained after the rally along with demonstrators and taken to Orsha district police department.

Freelance journalists working for TV channel Belsat, Alyaksandr Barazenka and Katsyaryna Bahvalava, went to the police station to get a comment from a detained opposition activist, only to be detained as well. Pending trial they spent the night in jail.

Abakunchyk and Bakhvalava were ordered to pay fines. Abakunchyk was accused of participating in an unsanctioned mass event under Aryicle 23.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences and fined approximately €280. Bakhvalava was accused of illegal production and distribution of media products and disobeying the police under Article 22.9 and Article 23.4 of the Code of Administrative Offences and fined approximately €340.

Up to 18 journalists and bloggers were arrested while covering the protests, IFJ reported.

Conservative MP Jean-François Mancel filed a proposed law to the National Assembly on 10 March which intends “to remove protection of the confidentiality of journalistic sources if protection of the public interest justifies it“.

The proposed law reads: “Contrary to what is generally said by journalists and their representatives, the systematic protection of sources’ confidentiality and the will to further reinforce it seriously compromises the respect of individual freedoms and the protection of civilians against acts of aggression from the media.”

Mancel accused journalists who have covered allegations of fraud involving conservative candidate François Fillon of going after the candidate unfairly, for instance on his Twitter account.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1490021682242{background-color: #d5473c !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}” el_class=”text_white”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490021461628{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/MMF_report_2016_WEB-1-1A.jpg?id=85872) !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hakan Büyük, a Turkish-Dutch journalist for the newspaper Zaman Vandaag has been receiving death threats on Twitter, news portal Villamedia reported on 13 March.

The threats began after a diplomatic row between Turkey and The Netherlands led to violent pro-Erdogan protests in the streets of Rotterdam. Earlier, Dutch authorities banned a Turkish minister from campaigning for an upcoming Turkish referendum.

Büyük received at least ten threats in Turkish, one of which read: “We will not arrest you, you will be killed.” He has filed charges with the police.

Zaman Vandaag was founded by Gulen sympathisers, who are being blamed for the failed coup in Turkey in the summer of 2016.

Unidentified protesters assaulted and verbally harassed two different TV crews during a pro-opposition protest on 10 March in Skopje, news agency META reported.

Hristijan Banevski, a reporter for private broadcaster TV 24, was “firstly verbally attacked and then hit in the head with a stick holding a flag during the protest in Skopje”.

That same night, a TV Telma crew was verbally harassed while interviewing protesters. Without giving much detail, the channel reported that their journalists were cursed at.

Local journalists’ associations have called upon the Macedonian institutions to take appropriate measures and to come out in defence of the journalists, news agency META reported.

President of the Association of Journalists of Macedonia (ZNM), Naser Selmani, underlined that what is worrying is that public officials, including representatives of state institutions, participated in these coordinated attacks.

In the last four years, according to ZNM’s data, 44 attacks against journalists were reported in Macedonia. Out of these, 19 occurred in 2016.

Officers from the Russian Security Service (FSB) detained reporter Igor Zalyubovin and photographer Vladimir Yarotsky for the Moscow-based independent news magazine Snob on 7 March, the publication said in a statement. The journalists were in the apartment they rented to report on daily life in the city of Svetogorsk.

An article was planned as a response to Svetogorsk Mayor Sergey Davydov’s 1 March claim that there were no homosexuals in the city, and that it was a “city without sin,” according to press reports.

On 7 March, the Committee to Protect Journalists issued a statement saying Russian security services should stop harassing and obstructing journalists and should allow them to work unimpeded.

To visit Svetogorsk requires either a Schengen visa to enter via Finland, an invitation from a local resident, or a special permit from the FSB, according to 2014 legislation. Snob’s editor-in-chief, Yegor Mostovshikov, told the news website Meduza today that his outlet did not apply for a permit from the FSB “because it takes up to 30 days to get it.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490021029215-ef5a3b8c-778c-2″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Feb 2017 | Bahrain, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Nabeel Rajab, co-founder and President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, was set to be tried on 21 February for a series of charges including “deliberately spreading false information and malicious rumours with the aim of discrediting the State, “insulting a statutory body,” “disseminating false rumours in time of war” and “offending a foreign country.” The “foreign country” at issue is Saudi Arabia.

On 21 February the High Criminal Court of Bahrain postponed the trial based on charges related to tweets until 22 February. The hearing on charges related to televised interviews has now been postponed to 7 March.

In order to allow judges to hear the testimony of the investigation officer and to give Rajab’s lawyer access to copy of the evidence, the tweet-related trial was pushed back from February 22 to 22 March.

Rajab, who is a 2012 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award winner and a judge for the 2016 awards, has been in police custody since June 2016 after he wrote an article exposing human rights violations in Bahrain for the New York Times.

On 3 February, 19 and two individuals organizations supporting human rights and freedom of expression sent a joint open letter to Boris Johnson calling for Rajab’s release.

If convicted, Rajab faces 18 years total in prison.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1487947058044-297cb21b-a8cd-6″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]