12 Jun 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Tunisia

The Tunis Printemps des Arts (Spring of Arts), a modern contemporary art fair, ended on 10 June after 10 days of exhibitions and competition. The closing ceremony, which was supposed to be a celebration of art, was characterised by controversy, censorship and violence.

On Sunday afternoon, three ultra-conservative Islamists (reportedly two men and a woman) accompanied by a bailiff and a lawyer toured Palais El-Abdellia, the art gallery which hosted the fair’s closing ceremony. The group asked the fair organisers to take down two artworks they deemed “un-Islamic”.

One of the artworks in question illustrates a naked woman, whose intimate parts are covered by a Couscous plate (a popular Tunisian dish). The woman is surrounded by dark, bearded men. The second work illustrates a bearded superman carrying another bearded man in his arms.

“They said that they would come back at 6 pm, and that they would rather not find the paintings,” said Aicha Gorgi, a gallery owner and artist. “They did come back at 6pm, their number grew, and they gathered in front of Palais El-Abdelia,” she added.

Police interfered to prevent any clashes between the artists and the ultra-conservative group. But later on in the night and after the closure of the art gallery, the ultra-conservatives came back in larger numbers and succeeded in invading El-Abdelia art gallery. They burned and destroyed a number of artworks.

“Police did not allow them to enter, but they climbed over the rear walls and entered the gallery,” Gorgi said in a testimony given to Radio Mosaïque FM. “They burned the work of Faten Gaddass, and tore to pieces two linen artworks, one by Mohamed Ben Slama, and the second by a French artist. At my stand, I also found Aicha Filali’s work destroyed.”

This is not the only censorship story which characterised this year’s Printemps Des Arts edition. Last week, young Tunisian artist Elektro Jaye claimed that the state put pressure on the fair’s organisers to take down his work.

7 Jun 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Tunisia

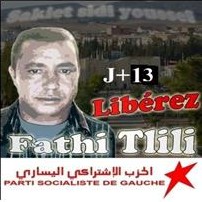

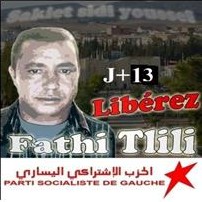

13 days after police arrested him, Fathi Tlili, a coordinator for the Leftist Socialist Party (Le Parti socialiste de gauche in French), is still behind bars.

The arrest followed Tlili’s participation in protests which swept Sakiet Sidi Youssef, a small and underprivileged town in the northwest of Tunisia. On 25 May, the town’s inhabitants organised a general strike demanding employment and a local development boost.

The strike, which paralysed the town’s little economic activity, ended in acts of vandalism when unemployed protesters set official buildings and state-owned cars on fire.

Police are accusing Tlili of “inciting riot”, and of “breaking down” the local delegation’s rear door building. The PSG has denied these charges, claiming that Tlili and other party activists tried to stand up to acts of vandalism.

In a communiqué released on 3 June, PSG Secretary General Mohamed Kilani described the legal proceedings against Tlili as “a political trial”. He claims Tlili was badly treated while in prison.

“After visiting him in prison, Fathi’s wife asserted that her husband was physically abused, and badly treated. She noticed the bruises on his body,” the communiqué stated.

The Tunisian extreme left is often blamed for fuelling protests and social unrest. I an interview given to Al-Jazeera last January, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki accused the “extreme left” of “manipulating, and politicising social protests in order to stir up trouble”.

6 Jun 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

Tunisian graffiti artist Elektro Jaye was recently censored at the Tunis Pintemps des Arts (Spring of Arts), a modern contemporary art fair which exhibited more than 500 art works this year.

“One of the fair’s organisers Luca Luccattini literally told me that the state had put pressure on him to remove my posters”, Elektro Jaye told Index.

Lucattini, the fair’s director, told Webdo.tn that one piece by the artist has been taken down, but for administrative reasons rather than pressure from authorities.

The artwork in question (on the far left) features the star and crescent from Tunisia’s flag, along with the Christian cross and the Star of David. The images are combined with the phrase “La République Islaïque de Tunisie”, which translates as “The Islaic Republic of Tunisia”. Islaic is a play on words, “Is” being taken from “Islam” and “laic” from the French word for secularism, “laïque”.

“The idea suggested here is that the religious should not interfere with the state’s decisions, nothing more! In my posters there is only a message of peace, and tolerance,” says Elektro Jaye.

Tunisia has had a heated debate about secularism and Islamism, dominating political discussions in the months following the fall of Ben Ali. Many Tunisian artists did not hide their desire for a secular state, and have used their work to express their view that religion should be kept aside.

While Elektro Jaye was unable to display his work at the art fair, he eventually succeeded in having his work displayed.

“Aicha Gorgi suggested that I display my works in her gallery. Some scandalmongers have been suggesting that this was just a marketing ploy. This is totally wrong.”

22 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

On 28 May Monatir Appeal Court is expected to issue a verdict in the case of two atheist friends Jabeur Mejri and Ghazi Beji. In March a primary court sentenced the two to a seven-and-a-half year jail term over the publishing of prophet Mohammedd cartoons.

Defense lawyers chose only to appeal on behalf of Jabeur Mejri, since Ghazi Beji has fled the country. “We would lose appeal if we defend him [Ghazi Beji] in absentia”, said Bochra Bel Haj Hmida, a defense lawyer, and a human rights activist.

To convict the two friends, Mahdia Primary Court employed Article 121 (3) of the Tunisian Penal Code, which states the following:

“The distribution, putting up for sale, public display, or possession, with the intent to distribute, sell, display for the purpose of propaganda, tracts, bulletins, and fliers, whether of foreign origin or not, that are liable to cause harm to the public order or public morals is prohibited.”

Anyone who violates this law risks a fine of 120 TND (76USD) to 1200 TND (760 USD), and a jail term of six months to five years.

Article 121 (3), adopted on 3 May 2001 as a way to tighten control over press freedom, was repeatedly used during the post Ben Ali era.

The controversial law earned Jabeur Mejri and Ghazi Beji a five-year jail term, and a 1200TND (760USD) fine for publishing content liable to “disturb public order”, and six months for “moral transgression”. The court also sentenced them to two more years in prison for “insulting others via public communication networks”.

The Court of First Instance of Tunis also used this law to fine both Nessma TV boss Nabil Karoui over the broadcast of French-Iranian film Persepolis, and Nasreddine Ben Saida, the general director of the Arabic-language daily newspaper Attounissia over the publishing of a front page photo of a Real Madrid footballer with his naked girlfriend.

“As lawyers and activists we are volunteering to defend Mejri, and Beji. This is our tool to combat abusive laws adopted during the Ben Ali regime. But it is the job of the legislative branch, that is the national constituent assembly, to amend such laws,” explained Mrs Bel Haj Hmida.