5 Jul 2013 | Digital Freedom

While the official Chinese reaction to Edward Snowden’s Prism leaks has been muted, ordinary Chinese have been quick to point out the US’ double standard on espionage, Alice Xin Liu writes

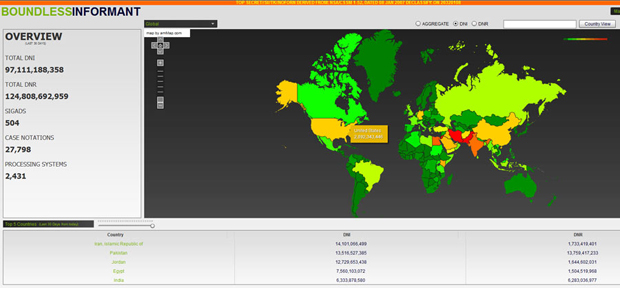

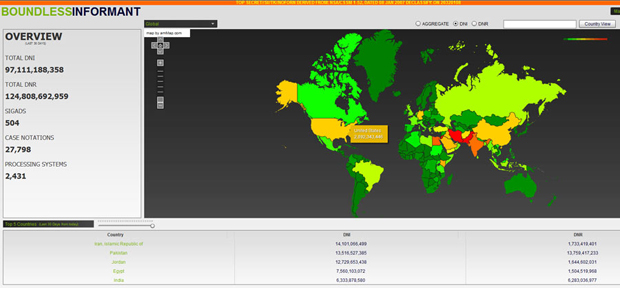

Snapshot of Boundless Information global heat map of data collection. The color scheme ranges from green (least subjected to surveillance) through yellow and orange to red (most surveillance). (NSA)

(more…)

24 Jun 2013 | In the News

INDEX POLICY PAPER

Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?

While in principle the EU supports freedom of expression, it has often put more emphasis on digital competitiveness and has been slow to prioritise and protect digital freedom, Brian Pellot, digital policy advisor at Index on Censorship writes in this policy paper

(Index on Censorship)

BELARUS

ZHREO against the Belarus Free Theatre

Authorities continue to pressure against the Belarus Free Theatre. This time, through the housing and maintenance services.

(Charter97.org)

BOSNIA

Bosnians protest as political stalemate leads to infant death

In the shadow of events in Turkey and Brazil, Bosnians have been taking to the streets. For over a week, citizens of the small Balkan country have been protesting their leaders’ failure to pass a new law on citizen identification numbers, leaving babies unable to travel for medical care. Milana Knezevic writes

(Index on Censorship)

BRAZIL

Unity in defense of freedom of expression of working-class and youth organisations

The right wing is attempting to co-opt the huge demonstrations of the last few days by introducing a bias towards nationalism, against corruption, against PEC 37, etc. There have also been some placards against abortion, for a military coup, and for Joaquim Barbosa (President of the Supreme Court who condemned the PT leaders without evidence in Criminal Case 470) to become the new president of the republic.

(In Defense of Marxism)

CANADA

More is less: Feds boost information services amid complaints of tighter control

The federal government employs nearly 4,000 communications staff in the public service, an increase of 15.3 per cent since the Conservatives came to power in 2006.“sanitized” results.

(Winnipeg Free Press)

CHINA

Weibo Censors Difficult to Detect

For Tea Leaf Nation, Jason Ng claims that Sina Weibo’s censorship has become increasingly opaque in the past months with the reduction of keyword blocks that allow one to easily discern banned search terms. Now, users can find previously banned terms like Xi Jinping or even June 4th, but the search yields “sanitized” results.

(China Digital Times)

EGYPT

Egypt’s army to step in if anti-Morsi rallies become violent

Army says it will intervene because demonstrations against President Morsi are ‘an attack on the will of the people’

(The Guardian)

GLOBAL

Net censorship may backfire

The impulse to protect our children is universal and for so long now filtering or blocking certain Internet sites has been a part of that. There are strong justifications for this, of course. While the Internet is a valuable tool for both information and communication, there is much that it offers is of no value to anyone and considerable potential harm.

(Arab News)

JAPAN

‘Hate speech’ in the media, but not the legal code

This writer, on previous occasions, has expressed irritation over the recent tendency for the vernacular media to rely heavily on English borrowings for neologisms with socially negative connotations, such as sexual harassment, stalking and domestic violence — to name three examples.

(The Japan Times)

MACEDONIA

Macedonia must not silence critical media, UN expert says

Macedonia must allow space for critical media, Frank La Rue, UN special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of expression said on June 21 2013, saying the closure of a television station and some newspapers in 2011 sends worrying signals about free expression in the country.

(The Sofia Globe)

RUSSIA

Pussy Riot in London: “We are now in a fight. When the world is less sexist, then we will celebrate”

Index’s Padraig Reidy speaks to two members of the Russian feminist punk group on a secret trip to the UK

(Index on Censorship)

UNITED KINGDOM

In Britain, a debate over freedom of the tweet

After the recent slaying of a British soldier in a suspected Islamist extremist attack, angry social media users took to Twitter and Facebook, with some dispatching racially and religiously charged comments. For at least a half-dozen users, their comments landed them in jail.

(Richmond Times-Dispatch)

UNITED STATES

Edward Snowden: diplomatic storm swirls as whistleblower seeks asylum in Ecuador

Whistleblower escapes from Hong Kong to Moscow on a commercial flight despite a formal US extradition request

(The Guardian)

Free speech on the Strip

Some good news on the free speech front: Clark County government now has a hands-off approach on protests, demonstrations and political expression.

(Las Vegas Review Journal)

‘Stop word police!’: Glenn Beck defends Paula Deen’s right to speak

@glennbeck: Paula dean.Shame on U. 2013 not 1953. also agree with bill mahr who I despise but defended after 9.11.Fight for ALL speech.

(Twitchy)

Previous Free Expression in the News posts

June 21 | June 20 | June 19 |

June 18 | June 17 | June 14 | June 13 | June 12

17 Jun 2013 | In the News

CANADA

Free speech doesn’t cover libel or slander, in any language

It was back in 2006 that Vancouver lawyer Roger McConchie warned in a CanWest News Service interview that libel cases were on the increase in Canada and that the Internet was “the single most important reason for the increase.” His law firm, McConchie Law Corp., has kept track of Canadian cases since the first Internet libel suit was launched in 1995, with one Julian Fantino awarded $40,000 in damages.

(Times Colonist)

CHINA

Is Hong Kong really free or does Beijing call the shots

The flight of a government whistle-blower – or possible fugitive from justice – to the quasi-democratic Chinese enclave of Hong Kong has given this former British colony a bit of free PR.

(Patriot-News)

EGYPT

Egyptian Politician: Jews Use Human Blood for Passover Matzos

The Muslim world is keeping the centuries old “matzah blood libel” alive and well – even in Egypt, with which Israel has a peace treaty.

(Arutz Sheva 7)

EUROPEAN UNION

EU deal to protect film, TV, sets the stage for transatlantic trade pact

Compromise protecting film, TV from market liberalisation permits progress on transatlantic talks but could stoke protectionism in US

(South China Morning Post)

INDIA

EU not ready to give India ‘data secure’ status

The European Union has picked holes in India’s data security system and suggested that a joint expert group be set up to propose ways on how the country should tighten measures to qualify as a data secure nation.

(The Hindu)

MIDDLE EAST

Lifting of censorship boosts Arab media

Lifting of media censorship in Arab Spring countries has boosted local channels which have stepped into the role Aljazeera had been playing in the region for years, according to a new book.

(The Peninsula)

UNITED KINGDOM

Met chief ‘faces libel claim over Plebgate’

Britain’s most senior police officer faces being called to testify on oath over leaks in the Andrew Mitchell ‘Plebgate’ affair.

(Daily Mail)

The home of free speech closes down for NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden

The news that the Government is trying to prevent whistleblower Edward Snowden from travelling to this country by telling airlines not to accept him as a passenger has made me furious.

(The Independent)

DIY YouTube directors to self-regulate under new censorship scheme

Film watchdogs in three countries including UK are to pilot a program in which amateur video-makers can self-regulate

(The Observer)

UNITED STATES

First Amendment Ban on ‘gruesome images’ threatens free speech

For those of us who worry about the vitality of free speech in the “land of the free,” recent news isn’t good. On June 10, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review a Colorado appeals court decision banning anti-abortion activists from displaying “gruesome images” of mutilated fetuses that might be seen by children.

(Pantagraph)

11 Jun 2013 | In the News

CANADA

Rob Ford wins partial costs in wake of failed libel suit

Boardwalk Pub restaurateur George Foulidis must pay mayor and Bruce Baker $137,000, judge ruled Monday. (Toronto Star)

CHINA

Beyond the Great Firewall: How and What China Censors

China’s lack of transparency has long posed a daunting challenge to outside observers trying to understand what the government’s interests, goals, and intentions are. Gary King, a Professor in Government at Harvard University, has provided telling new insights into these questions with his research on the government’s censorship of social media websites. (The Diplomat)

EGYPT

Maspero in crisis: report

The AFTE also claimed former head of the state-run TV sector Essam El-Amir resigned last December because of intervention in the coverage of the presidential palace clashes. (Daily News Egypt)

HONG KONG

Yes, Free Speech Is Big in Hong Kong—Because They Must Constantly Defend It

Hong Kong has a strong tradition of free speech.” That’s how Edward Snowden, the 29-year-old leaker who slammed National Security Agency surveillance as an “existential threat to democracy,” described his decision to flee to China. (New Republic)

RUSSIA

Accusations of censorship as more exhibitions are shut down at Perm festival

The White Nights festival in Perm has come under pressure after four of its exhibitions have been closed, seemingly at the request of unhappy local politicians. In response, Marat Guelman, one of the festival’s organisers has accused critics of political game-playing. (Calvert Journal)

UNITED STATES

Should the Lubbock AJ host Blogs?: Freedom of Speech Issues

In the spring of 2012 I was invited to begin a blog hosted on the Lubbock AJ on-line site. Having been drawn into the arena of public debate during the effort to close the city’s Health Department I felt that such an opportunity to encourage civic involvement was a good idea.

(Lubbock Avalanche-Journal)

‘Free Speech’ Doesn’t Include Showing Dead Fetus Posters to Kids

The Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal of an anti-abortion protestor who claimed his free speech was violated by the state of Colorado. By declining to hear the case, the Court allowed a lower court ruling barring certain types of anti-abortion protests in public areas to stand, which, on its surface, might sound like a good thing. But the truth’s a little messier.

(Jezebel)

As libel trial losers battle $1M legal bill, FBI probes claimed mid-trial DUI set-up of their lawyer

The trial in a defamation case between two radio shock jocks in Florida has been over for months. But there’s no end in sight to continuing issues involving the law firms for both sides, the Tampa Bay Times reports.

(ABA Journal)

A twist in the tale of the Christian valedictorian

You’ve probably heard about the South Carolina high school valedictorian who tore up his prepared speech at graduation ceremonies and instead recited the Lord’s Prayer, to cheers and applause. But there is a twist in the tale of Roy Costner IV, who has become a poster boy for Christian conservatives.

(Los Angeles Times)

VIETNAM

Vietnam bans action movie despite removal of violent scenes

Vietnam latest action movie about gang fights in Ho Chi Minh City’s Chinatown has been officially banned after the censors disapproved of the new, censored version. (Thanh Nien)