1 Jun 2020

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1591025337019{padding-top: 55px !important;padding-bottom: 155px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/trump-shadow-pic-for-slapps-credit-3-scaled.jpg?id=113748) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}” el_class=”text_white” el_id=”Introduction”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”A gathering storm:

the laws being used to silence the media” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1590689449699{background-color: #000000 !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_raw_html]JTNDZGl2JTIwc3R5bGUlM0QlMjJhbGlnbiUzQWNlbnRlciUzQm1hcmdpbiUzQWF1dG8lM0JiYWNrZ3JvdW5kLWNvbG9yJTNBcmdiYSUyODAlMkMwJTJDMCUyQzAuNSUyOSUzQiUyMiUzRSUzQ3AlMjBzdHlsZSUzRCUyMnRleHQtYWxpZ24lM0FjZW50ZXIlM0J3aWR0aCUzQTYwJTI1JTNCbWFyZ2luJTNBYXV0byUzQiUyMiUzRUElMjByZXZpZXclMjBvZiUyMGhvdyUyMGxhd3MlMjBhcmUlMjBiZWluZyUyMHVzZWQlMjBpbiUyMEV1cm9wZSUyMHRvJTIwYnJpbmclMjBhY3Rpb25zJTIwYWdhaW5zdCUyMGpvdXJuYWxpc3RzJTNDJTJGcCUzRSUzQyUyRmRpdiUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Introduction

“It’s crippling,” explained Stefan Candea, a journalist and co-founder of the Romanian Centre for Investigative Journalism, when asked about the centre’s experience of being sued for its work. “It’s a major crippling of the workflow and of resources.”

Across Europe, laws are being used by powerful and wealthy individuals in the hope of intimidating and silencing journalists who are disclosing inconvenient truths that are in the public interest. These legal threats and actions are crippling not only for the media but for our democracies. Instead of being empowered to hold power to account, as is fundamental to all democratic societies, journalists face extortionate claims for damages, criminal convictions and, in some cases, prison sentences in the course of carrying out their work.

“For me it was a shock, maybe because it was the first time I was dealing with the penal code,” responded Polish investigative journalist Karolina Baca-Pogorzelska when asked about her experience of facing a criminal lawsuit. “I didn’t do anything wrong [but] at trial, I passed prisoners in handcuffs in the corridors. It broke me completely.”

In undertaking research into the scope and scale of vexatious lawsuits – or strategic lawsuits against public participation (Slapps) – against journalists and media outlets in Europe, Index hopes to help address the current dearth of information around the phenomenon. The purpose of this first report – which looks at EU states, the UK and Norway – is to provide a concise snapshot of the legal systems that are being abused in favour of the powerful, a worrying trend that we are seeing across the continent. The report is intended as a foundation for forthcoming research.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/ijAAWRdkeV0″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Gill Phillips, director of editorial legal services at Guardian News and Media, said: “Against the background of the growing trend in Europe of threats to reporting by using litigation as a means of inhibiting, intimidating and silencing journalists and others working in the public interest, this timely report provides succinct and helpful jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction guidance into the main legal danger areas for journalists and others.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The law is an essential component of understanding the extent to which journalists are vulnerable to legal threats and actions. But culture, which shapes the law but is also separate from it, should also be taken into account. Although it is more difficult to analyse, it determines the extent to which society sees the media as essential to democracy, and the extent of people’s readiness to resort to law to resolve disputes.

“A lot of public officials don’t understand the media as a watchdog. They still have this old communist kind of definition of the media. They think the media should be reporting what the government does for the nation,” said Beata Balogová, editor-in-chief of the newspaper SME, as she explained the impact of culture on the media in Slovakia.

“Very often they just use a lawsuit as a way of scaring journalists or trying to discourage them from pursuing some of the reports.”

Please note you can download this report as a PDF or view it as a flipbook.

Main report

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113571″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Austria”][vc_column_text el_id=”austria”]

Austria

According to Georg Eckelsberger of the investigative media outlet Dossier, letters threatening legal action are often received by journalists in Austria.

Defamation, which is a criminal offence, is most often used. In the criminal code, it is defined as asserting or disseminating a fact that may defame or negatively affect public opinion of another person. It is punishable by a fine or one year in prison, although the latter has never been used against journalists.

The civil code and the media law also provide for significant damages to be awarded for loss of honour. The civil code is particularly open to abuse as the possible damages are uncapped and it does not provide the same weight as the media law to a public interest defence. In 2019, the civil code was used to sue Kyrgyzstani news outlet 24.kg in what was labelled by Article 19’s Barbora Bukovska as “a clear case of so-called libel tourism”.

Concerns have also been raised over the extent to which public interest is taken into consideration in other civil law cases against the media. In 2015, Dossier was ordered to pay nearly €2,000 to a plaintiff after being convicted of trespassing during an investigation, despite the findings of the investigation being uncontested.

Anyone who has been the subject of an incorrect statement in the press has the right to have a reply published, though the media has the right to refuse to publish a reply if the information was demonstrably true.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113577″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Belgium”][vc_column_text el_id=”belgium”]

Belgium

Although defamation is a criminal offence, punishable with a fine or prison sentence, journalists are never brought to court on such charges. This is mostly due to the fact that criminal press offences can be heard only by jury-based tribunals, which are costly and time-consuming. According to a 2017 report by the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, “the media enjoy a de facto exemption from criminal defamation laws”. In practice, this does not completely stop plaintiffs from filing criminal lawsuits against journalists.

Civil defamation is addressed as a tort under the civil code. The claimant must demonstrate the fault, the damage and the causal link between the fault and the damage. There are no limits or precise guidelines on the amount of pecuniary or non-pecuniary damages that may be awarded, but damages for civil defamation usually range between €1,000 and €10,000.

Concerns have been raised about Belgian courts’ propensity to grant pre-publication injunctions at the request of private companies that claim their rights have been violated. In 2015, a court in Namur blocked the launch issue of Belgian investigative magazine Médor following a request from a pharmaceutical company that claimed it had been wrongly accused in one of its articles. The ban was annulled two weeks later.

Anyone referred to in a newspaper, magazine or audio-visual broadcast has the right to reply. Although the right of reply does not apply to internet-based media, case law applies and there is a legal proposal in the pipeline.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113580″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Bulgaria”][vc_column_text]

Bulgaria

While lawsuits are not the only tool used to intimidate and discredit journalists in Bulgaria, they remain a serious threat to investigative journalism, which is already struggling in the country.

Criminal defamation is often used to bring legal actions against the media, including against individual journalists. Insult and slander remain criminal offences, punishable by fines but not imprisonment. Concerns have been raised around the ability of the courts to protect journalists from vexatious criminal charges, especially following the conviction of Rossen Bossev on defamation charges last year.

Compensation may be sought under the Obligations and Contracts Act, which allows for unlimited non-pecuniary damages to be awarded. The burden of proof is on the defendant. According to the Radio and Television Act, the media will not be liable for information that has been received through official channels, for quoting official documents, or for accurately reproducing public statements.

At least one effort has been made to vexatiously sue a journalist by claiming that constitutional rights, specifically the right to dignity and reputation, was violated. However, this was rejected by the court.

Anyone affected by radio or television broadcasting has a right to respond by making a request to do so in writing within seven days from the date of the broadcast. The response can be neither edited nor shortened and should be published in the next episode or within 24 hours of receipt. The Ethical Code of the Bulgarian Media provides for a right of reply in printed media, but not all print outlets have signed the code.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113612″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Croatia”][vc_column_text]

Croatia

According to a recent survey by the Croatian Journalists Association, there are currently at least 46 criminal lawsuits and 859 civil lawsuits filed against publishers, with claimants seeking the equivalent of approximately €9 million in damages.

Defamation and insult, punishable with fines but not imprisonment, are most often used as justification to bring legal action against the media. The offence of “heavy shaming” was abolished with changes to the criminal code, which took effect in January 2020. Although journalists are acquitted in most cases, a significant number of criminal lawsuits continue to be filed.

Civil lawsuits can be brought against publishers under the Media Act and against authors (journalists) under the Obligations Act. In a case against a journalist under the Obligations Act, the plaintiff has to prove that the defendant intentionally caused the damage, but the burden of proof under the Media Act is on the publisher. According to media lawyer Vesna Alaburić, this is why journalists are rarely sued in civil proceedings. She says that when they are, lower courts often fail to strike a fair balance between the right to freedom of expression and the right to privacy and reputation. Typical compensation for non-pecuniary damages is between the equivalent of €2,500 and €4,000.

The Croatian constitution guarantees the right for individuals to correct public information that has violated their constitutional and legal rights.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113641″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Cyprus”][vc_column_text]

Cyprus

Although the attorney general has the authority to allow for criminal prosecution in some specific cases, defamation is no longer a criminal offence and is instead addressed under the Civil Wrongs Law. The plaintiff must prove that the publication is defamatory or that there has been malice. If it is defamatory then journalists or media outlets must prove that either the information is accurate or that it is in the public interest. European Court of Human Rights principles are generally applied.

Legal actions for violation of privacy can be brought under the constitution, which protects the right to privacy and the right to private correspondence. According to Prof Achilles Emilianides, of the University of Nicosia, compensation generally ranges from €3,000 to €20,000.

Journalists have expressed frustration over the slow pace of the judicial process, with some cases continuing for up to a decade. According to research from the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), first-instance proceedings in Cyprus are among the slowest in the EU.

Gagging orders and injunctions can be used for both privacy and defamation, and although they are rarely granted, serious concern has been raised over their use in the past.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113644″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Czech_Republic”][vc_column_text]

Czech Republic

Defamation is a criminal offence, punishable with a maximum sentence of between two and three years in prison (depending on the nature of the alleged defamation) or a prohibition from practising a certain profession. Charges can be brought only if the published information is alleged to be false. In practice, accusations of criminal defamation are quite rare.

The civil code provides that if a person is to be held liable for the violation of the right to dignity, esteem, honour or privacy, all three of the following conditions must be met: an unjustified infringement capable of causing moral damage, moral damage having been suffered, and a causal connection between the infringement and the damage. Financial compensation must be provided if someone’s rights have been violated (unless other remedies are sufficiently effective). While the civil code does contain a “principle of decency”, questions have been raised about its capacity to prevent vexatious claims. Under the Press Act, the publisher is legally responsible for the published content.

The right to dignity, honour, reputation and private life are protected by the constitution. A right of reply is provided for under the Radio and Television Broadcasting Act and the Press Act and stipulates that it should be limited to a factual assertion rectifying, completing, or making more accurate the assertion in the initial broadcast. The publisher is obliged to publish the reply.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113650″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Denmark”][vc_column_text]

Denmark

Denmark has comparatively few laws to regulate the press, with the main media law principle being to balance conflicting rights. Honour, privacy and personality rights are protected by the criminal code, the Marketing Regulation and case-law principles that have been adopted from the ECtHR.

Defamation is a criminal offence, punishable with a fine or imprisonment for up to one year – increasing to two years if the statement is found to have been made in bad faith. Although factual allegations may also be considered defamatory, there is an exemption from criminal liability if the statement was made where there was reasonable cause for it, in good faith, in the public interest or in the interest of the alleged offender or others.

Lawsuits against the media are uncommon in Denmark, with most complaints being brought through the press council, which will require its decision to be published in the event of a code breach.

Requests for replies must be allowed concerning factual information if the complainant might suffer from “significant financial or other damage” and if the accuracy of the information is not entirely indisputable.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113653″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Estonia”][vc_column_text]

Estonia

The Estonian Association of Journalists expressed concern that efforts to intimidate or threaten journalists may be rising. Legal threats and actions have mainly come from private individuals and companies, but there has been an increase in legal threats from politicians in recent years. Although threats from politicians have become more direct, intense and frequent, they have not gone beyond threats for now.

Criminal defamation charges can be brought only by a judge, a representative of a state authority or a foreign head of state, and are punishable with fines but not prison sentences.

Legal action is brought mostly under the civil code, which stipulates that rights must be exercised in good faith and not with the objective of causing damage to another person. It provides for compensation to be awarded in case of damage. Lawsuits targeting individual journalists were, until recently, very rare. In November 2019, Harju County Court decided that two journalists were held liable for the content they created. A similar proceeding is currently pending in the courts.

The constitution protects individuals’ right to not have their honour or good name defamed and provides for the right to free speech to be curtailed in order to protect it. Anyone who believes his or her reputation to have been damaged by a broadcast or publication may submit a right to reply. The publication can reject a request if it is unjustified or defies generally accepted moral standards, but it would put the outlet at risk of a lawsuit.

Both press councils – Pressinõukogu and Avaliku Sõna Nõukogu – have roles in holding the media to account, but the decisions of only the Pressinõukogu are published by the media.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113655″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Finland”][vc_column_text]

Finland

Defamation is a criminal offence, punishable with a fine. Aggravated defamation, punishable with up to two years imprisonment, can be used for acts that cause “considerable suffering or particularly significant damage”. The law requires that only false information can lead to criminal liability. One journalist who was sued for criminal defamation last year credited the prosecutor with deciding quickly that no crime had been committed. Private claims for damages resulting from defamation can be brought only in conjunction with criminal charges, and any compensation awarded is dependent upon the outcome of the criminal case.

The Tort Liability Act provides for compensation to be awarded if the plaintiff’s liberty, peace, honour or private life have been violated. Compensation rarely exceeds €10,000. Privacy, honour and the sanctity of the home are also protected under the constitution.

Although the Finnish Council for Mass Media can only sanction code breaches by ordering the media to publish its decision, the council may still have a role in creating a less litigious media culture. The council does not handle a complaint if a corresponding court case is being brought. Anyone who can demonstrate that published material is incorrect or offensive has the right to demand equal space for a correction.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113657″ img_size=”full” el_id=”France”][vc_column_text]

France

France is known as a plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction and fears have been raised about it becoming a libel tourism hotspot. According to media lawyer Emmanuel Tordjman, legal threats and actions have been increasing against the media in recent years. He says that most actions are taken under the 1881 Media Law, but they are increasingly being taken under the criminal code in an effort to bypass the safeguards that exist under the media law.

The 1881 law guarantees freedom of expression for the press, but also criminalises defamation and insult and makes them punishable with fines of up to €12,000. When defamation is committed against public officials – including the president, ministers and legislators – the maximum fine increases to €45,000. In practice, this fine is usually much lower. Individuals claiming defamation must bring legal action within three months of publication.

A plaintiff may also choose to take a civil case against the media, but the procedure will still be subject to the 1881 law; the only difference is that civil remedies will be awarded and the defendant cannot be fined. In both civil and criminal cases, the media must prove either that the published information was true or, if it fails to meet that standard, that it was published in good faith.

Generally, the rights of journalists are well protected, as French case law is strongly influenced by ECtHR case law. In March 2019, the Paris Court of Appeal ordered Bolloré SA to pay France Télévisions €10,000 in damages for frivolous proceedings after the company sued the media organisation in commercial court for €50 million in damages over a report scrutinising the company’s activities in Africa.

The 1881 media law stipulates that anyone who has been named or depicted in the media has the right to reply. It must be published within three days of receipt, otherwise a fine of €3,750 fine is issued.

Although it does not fall neatly under the umbrella of a Slapp, the use of national security legislation to punish journalists for publishing information that is in the public interest is also a matter of significant concern. National security legislation provides no exceptions for journalists and there is no public interest defence. It carries a prison sentence of up to five years and a €75,000 fine.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113659″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Germany”][vc_column_text]

Germany

According to research carried out by Greenpeace, although there has been a discernible rise in the number of legal threats against journalists and activists, vexatious lawsuits rarely appear in courts due to a rigorous pre-litigation mechanism.

There are three defamation-related offences under the criminal code: insult, defamation and slander. All are punishable by either a fine or imprisonment. Action may also be brought under the civil code, although the fact that the burden of proof is on the plaintiff may disincentivise such suits from being brought. There is a provision for a responsible journalism defence, but not a wider public interest defence. In 2010, two journalists received criminal fines of €2,500 each for defaming two public prosecutors, after criticising their investigations as flawed. The appeals court overturned the sentence in 2012.

In January 2019, the Federal Civil Court issued a judgment that so-called “media law warning letters” (presserechtliche Informationsschreiben), used to intimidate and threaten media outlets from republishing coverage from other media, were justified only when they had concrete information on why publication would be illegal. According to Buzzfeed Germany’s editor-in-chief Daniel Drepper, because these letters mainly targeted celebrity news the judgment has changed little for investigative journalism. In the summer of 2019, Buzzfeed received nearly a dozen threatening letters after it published their undercover work exposing an “Alpha Mentoring” programme.

A plaintiff’s capacity to choose which court a case is heard in can also be a source of intimidation for journalists, as it results in cases being brought to cities that are perceived to be more plaintiff-friendly (such as Berlin, Cologne and Hamburg). The right of reply is regulated by the press law of each German state.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113661″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Greece”][vc_column_text]

Greece

Both criminal and civil defamation are used to intimidate and silence journalists, with public officials being among those having brought legal action against the media. There are five separate defamation-related offences in the criminal code, all of which are punishable with fines, imprisonment or both. Journalists have been sentenced on defamation-related offences, despite the ECtHR’s ruling that the imposition of prison sentences for defamation constitutes a violation of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In 2015, a report from the International Press Institute described Greece’s civil law framework as being “disproportionately hostile to the press”. Compensation, which usually ranges between €10,000 and €30,000, may be requested under either the civil code or the Press Law.

Serious concerns have also been expressed for the judicial system’s capacity to protect journalists from vexatious lawsuits, especially in light of a case against The Athens Review of Books. That case is now pending at the ECtHR.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113663″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Hungary”][vc_column_text]

Hungary

According to the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, despite the decline of independent media in the country, legal threats and actions continue to be used to intimidate and silence journalists.

Defamation, along with libel, is a criminal offence and punishable with a prison sentence. In practice, sentences tend to be converted to fines. The law favours public officials, who can count on the state’s legal counsel (free of charge) and the fact that the police will carry out the investigation. In both civil and criminal cases, proceedings are slow, sometimes taking several years to have a first-instance decision.

In 2018, the authorities brought criminal charges against the investigative journalist András Dezső for “misuse of personal data”, after he used publicly available Swedish records to challenge the claims made by activist Natalie Contessa af Sandeberg on Hungarian state television. At the time, the state prosecutor proposed to convict Dezső without a hearing.

Most lawsuits against the media are brought under the civil code. Claimants may be awarded restitution if court finds their rights to have been violated. They do not need to prove that the violation was harmful. According to investigative journalist Peter Erdelyi of 444.hu, the burden of proof weighs heavily on the media; proving that information was published in good faith is not sufficient.

There has been at least one instance of GDPR having been used to vexatiously target the media: in February 2020, a Hungarian court granted a preliminary injunction forcing Forbes Hungary to recall the latest issue of its magazine, which featured a list of the richest Hungarians. The injunction followed a complaint from the owners of Hell Energy, a Hungarian drinks manufacturer, who argued that the list was in breach of their privacy.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113665″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Ireland”][vc_column_text]

Ireland

Although Ireland ranks highly in press freedom indexes, its legal system is among the most vulnerable in Europe to abuse by vexatious litigators. In recent years, there have been some indications to suggest it is becoming a hub for libel tourism.

The fact that defamation is no longer a criminal offence offers little comfort to journalists and media outlets due to the lengthy legal process and significant costs associated with a defence. In some cases, the burden of a lawsuit could be high enough to close a media outlet for good. Few media outlets decide to take the risk of going to court, often opting to settle instead.

Most defamation cases are heard in the High Court, where juries decide the outcome and the amount of compensation that should be awarded. According to media lawyer Michael Kealey, four days defending a case in the High Court could cost between €200,000 and €250,000 in legal fees alone. There is no maximum limit on compensation and millions of euros have been awarded in the past. Because of the time and costs associated with exhausting domestic measures, the ECtHR provides little practical protection to most Irish journalists and media outlets. Limited protection is provided by Isaac Wunder orders, which requires plaintiffs to have consent from the court to file additional lawsuits against the same party against which they’ve already filed at least one. According to Kealey, Isaac Wunder orders have been used “somewhat sparingly in civil litigation”. He said he was unaware of a successful application for such an order in a media defamation action.

Anyone who has been personally affected by information disseminated by the media can bring a complaint to the Press Council. The main sanction is publication of the Press Council’s decision.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113667″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Italy”][vc_column_text]

Italy

Criminal defamation is commonly used and provides for sentences of up to three years. The criminal code provides for higher penalties to be applied if a political, administrative or judicial body has been defamed. Criminal cases can be brought up to three months after publication. In the past, journalists have been sentenced to up to two years in prison. Shorter sentences have been accompanied by fines of up to €15,000.

Civil lawsuits can be filed on their own or in addition to criminal lawsuits, and there is no limit on the amount of compensation that may be awarded. In the past, this has led to requests for millions of euros in damages. Civil lawsuits can be filed up to five years after publication. The time, money and resolve required to fight a lawsuit are also hugely burdensome; it can take up to eight years – and sometimes longer – to be either acquitted or convicted in a defamation case.

Right to replies are frequently requested and oblige print outlets to publish them within two days of the request if the information they originally published was either inaccurate or damaging to someone’s dignity. Despite efforts to introduce it, there is currently no legislation in place that obliges online news outlets to publish corrections.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113669″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Latvia”][vc_column_text]

Latvia

Defamation remains a criminal offence punishable with deprivation of liberty, community service or a fine. Criminal liability applies only in cases where information that was known to be fictitious and defamatory was publicly distributed. The criminal code has also been used to charge journalists with violating the confidentiality of correspondence.

Most legal action against the media is under civil law, which allows for anyone behind the publication or broadcast to be sued. A plaintiff can request an unlimited amount for non-pecuniary damages, but compensation rarely exceeds a few thousand euros for individuals. Media outlets may face higher damages. Cases usually take four or five years but have taken up to 10 in the past. Courts almost always take ECtHR case law into account and usually rule in favour of journalists.

According to media lawyer Linda Birina, GDPR is starting to be used in place of defamation as a basis to take legal action against journalists. She expressed concern over how the court would look at GDPR cases given that there is as yet no court praxis.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113671″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Lithuania”][vc_column_text]

Lithuania

Libel remains a criminal offence, punishable with a fine, arrest or imprisonment of up to one year. However, in practice criminal law is rarely used to bring legal action against the media.

According to a 2017 OSCE report, the Supreme Court of Lithuania often takes into account, cites and applies the standards developed in the jurisprudence of the ECtHR and the European Court of Justice.

Anyone who wishes to bring a civil claim for damages against a media outlet must first request a denial of information. A complaint can be filed with the Office of the Inspector of Journalist Ethics (out of court) without fulfilling this condition. According to the Lithuanian National Broadcaster, the right to request a denial of information is frequently used – particularly by businesspeople – who are dissatisfied with their investigations.

The civil code protects the right to privacy, honour and dignity and provides for the court to investigate requests for damages. The media is exempt from civil liability, even if the published information was untrue, as long as they can prove they acted in good faith to meet the public interest about a public person and his or her activities. According to CEPEJ’s research, Lithuania is among the fastest countries in the EU at resolving litigious civil cases, measured by the time taken by the courts to reach a decision at first instance: it typically takes less than 100 days.

The Law on the Provision of Information to the Public provides for the protection of honour and dignity as well as the protection of private life. According to the Office of the Inspector of Journalist Ethics, which investigates complaints relating to these protections, the law is rarely subject to abuse.

By law, anyone who is criticised in the media has the opportunity to justify, explain or refute false information within 14 days of publication. The outlet may refuse to publish the correction if its content “contradicts good morals”.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113673″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Luxembourg”][vc_column_text]

Luxembourg

Defamation and slander remain criminal offences, punishable with imprisonment of between eight days and one year, along with a fine of up to €2,000. Under the criminal code, journalists and media outlets may be exempt from criminal liability, even if the published information was untrue, as long as they can prove that they acted in good faith and in the public interest, that the allegedly defamatory statement was made live, or that it is an accurate quote from a third party. In practice, criminal defamation prosecutions against the media are rare. When they do occur, courts tend to follow the case law of the ECtHR.

The Luxleaks case saw a journalist and two whistleblowers charged with domestic theft, violating professional confidentiality, violating business secrets and fraudulently accessing a database. While journalist Edouard Perrin was acquitted, the whistleblowers were convicted and received fines and suspended jail sentences.

According to Luxembourg’s Union of Journalists, legal threats against journalists are rarely followed by legal actions. Most action comes from international rather than domestic plaintiffs, with defamation and privacy laws most commonly used. The right to privacy is protected by the constitution, as is the right to the secrecy of correspondence.

Right of reply works through a registered letter that has to be sent in an “appropriate” timeframe to the media. The media has the right to comment on the reply text. It has recently been extended to online media.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113675″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Malta”][vc_column_text]

Malta

Despite the decriminalisation of defamation in 2018, legal threats and actions remain a persistent and aggressive threat to journalists in Malta. What the European Parliament has called “serious shortcomings” in Malta’s rule of law intensify the climate of fear and intimidation facing the media.

Civil suits can be filed under the Media and Defamation Act in response to the publication of information that “seriously harms a person’s reputation”. Action may be brought against the individual journalist, the editor or the publisher. The act provides for certain defences, including a public interest defence. Up to €11,640 may be awarded in moral damages, in addition to actual damages. If the defendant published an “unreserved” correction or a reply from the plaintiff with the same importance as the original publication then the moral damages are capped at €5,000. In 2019, unpublished research by the Amsterdam International Law Clinic found that filing a separate claim for every sentence of an article (instead of grouping them into a single case) is a common tactic used to amplify the impact of a lawsuit.

Maltese journalists and media outlets have repeatedly received legal threats and lawsuits from abroad, especially from the UK and the USA, in apparent cases of libel tourism. Several public officials have been implicated in such cases. Efforts to prevent international lawsuits from being brought to bear on the media have so far been unsuccessful.

The Media and Defamation Act provides for anyone who has been misrepresented, been a victim of defamation or had his or her private life interrupted to submit a right to reply to contradict or explain the initial information. The media outlet must publish it within 48 hours of receiving it if it meets certain standards.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113677″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Netherlands”][vc_column_text]

Netherlands

Defamation remains a criminal offence, punishable with fines, imprisonment and, in extreme cases, loss of civil rights. Higher penalties are applicable if defamation is committed against a public official or foreign head of state. In practice, journalists are rarely charged, much less convicted of criminal defamation.

According to research carried out by Tess van der Linden of Radboud University, although Dutch procedural law contains provisions that can limit access to legal proceedings if the law is being abused to damage another person, it is quite rare that cases are dismissed based on these grounds, since courts tend to examine the merits of the case nonetheless.

Action is usually brought as a tort under the civil code. Case law, including ECtHR case law, is instrumental in its application. In principle, the burden of proof is on the claimant, but in practice the defendant will also have to provide evidence that they acted in good faith. Public interest is not an absolute defence but, along with the factual underpinning of the published information, it is essential to the outcome.

Media lawyer Jens van den Brink says he has noticed an increase in data protection laws being used to try to prevent journalists from publishing their stories, but he says that the courts are resilient against the abuse of these laws.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113679″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Norway”][vc_column_text]

Norway

Lawsuits against media outlets, editors and/or journalists in Norway usually relate to defamation, but sometimes also violation of privacy. Defamation is no longer a criminal offence and although violation of privacy continues to be criminalised, it is never used against the media.

Most claims are brought under the Compensation Act, which provides for compensation to be awarded in cases where an individual’s privacy, honour or reputation have been violated. In determining the liability of the journalist or media outlet, the veracity of the impugned statement is considered, as well as whether the statement was made in good faith. The Norwegian Union of Journalists has called for the act to protect journalists from being individually targeted, but its efforts have so far been unsuccessful. The balancing test between press freedom and the rights of the plaintiff, as developed in ECtHR case law, is fully adopted by Norwegian courts.

The Compensation Act provides for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages to be awarded. Compensation varies significantly but, according to media lawyers, journalists may expect to pay the equivalent of between €2,200 and €6,600 for non-pecuniary damages. Damages are set higher for media outlets – typically between €10,000 and €50,000. Media outlets usually cover their editors’ and journalists’ costs, including any damages they are ordered to pay.

Most people who have concerns about how they have been treated by the media tend to complain to the Norwegian Press Complaints Commission, the Norwegian Press Association’s self-regulatory commission. The commission has no power to award damages or impose fines: it reviews complaints and issues statements on whether or not there has been a breach the Norwegian Press Association’s code of ethics.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113681″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Poland”][vc_column_text]

Poland

Investigative journalist Wojciech Cieśla believes that there’s been an increase in lawsuits against the media in the wake of the Law and Justice Party’s (PiS) rise to power in 2015. Jarosław Kurski, deputy editor-in-chief of Poland’s largest daily newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, told the Committee to Protect Journalists last year that the PiS has been “flooding us with lawsuits”. The fact that these lawsuits have been mostly unsuccessful demonstrates that despite the challenges facing the judiciary, Polish courts have so far protected the media from such lawsuits.

Both civil and criminal law are used, by public officials as well as private companies and individuals, to target the media. Defamation is a criminal offence, punishable with fines, restriction of liberty and up to one year in prison. Higher penalties are applicable under certain conditions, including defamation of a head of state or the Polish nation. Defamation hearings are closed to the public unless the plaintiff requests otherwise. According to media lawyer Konrad Orlik, courts usually fine journalists convicted of defamation between €1,000 and €3,000. However, last year journalist Anna Wilk was given a three-year ban on working as a journalist. Although the ban was lifted in February 2020, she remains criminally convicted and had to the equivalent of about €1,600 in fines and to charity.

Legal action may also be filed under the civil code, which protects individuals’ personal interests – including dignity, image and privacy of correspondence. By law, anyone whose personal interests are threatened may demand that the actions be ceased and that compensation be paid. According to Orlik, although common courts take ECtHR decisions into consideration, Polish jurisprudence is considered superior in most cases.

The practice of “autoryzacja” – seeking the authorisation of interviewees’ quotes before publication – is widely practiced and provided for under the Press Law, although journalists may publish unauthorised quotes if the interviewee takes too long to reply or seeks to change the answers or add new information. The Press Law also provides for a right of reply to be sent to the editor-in-chief within 21 days and to be published free of charge.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113683″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Portugal”][vc_column_text]

Portugal

Defamation, insult and false accusation are criminal offences, punishable with hefty fines and up to two years in prison. Stricter sanctions are applicable for defaming individuals in certain professions, including public officials, diplomats, the president or foreign heads of state. However, according to media lawyer Francisco Teixieira da Mota, due to the ECtHR’s repeated condemnation of Portugal for violating the right to freedom of expression through its use of criminal defamation, courts are not as receptive to criminal complaints as they once were, and convictions have greatly reduced.

Most lawsuits against the media are brought under the civil code, which provides broad protection to individual rights – particularly the right to a good name. A journalist who publishes factual information that is capable of damaging a legal or natural entity’s good name may be ordered to pay damages.

In their decisions, some courts have raised questions about the extent to which accepting ECtHR case law is constitutional in Portugal, given that the Portuguese constitution provides equal protection to freedom of expression and individuals’ right to a good name, reputation, and privacy. The constitution also protects an individual’s right to make corrections to publicly available information.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113685″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Romania”][vc_column_text]

Romania

Although there have been proposals to recriminalise the act of insulting the state and its leaders, defamation is not currently a criminal offence. The criminal code may be used to bring legal action for violation of privacy, but the law provides for a number of circumstances, including public interest, in which disclosures do not constitute offences.

Lawsuits are brought against the media under the civil code, which protects the right to privacy, dignity and one’s image. The constitution stipulates that the civil responsibility of the published information rests with the publisher or director, the author and the owner. According to Active Watch Romania, some but not all court judgments take ECtHR’s jurisprudence into account. It has raised concerns that judgments in civil matters are inconsistent and unpredictable. Under the civil code, there is no limit on the moral damages that may be awarded, but under the audio-visual law, the maximum fine the media can be subject to is the equivalent of about €40,000.

Emergency gag orders – known as “presidential ordinances” – are also being used to silence journalists, with claimants seeking to force the removal of information and to prevent further information from being published. Significant financial penalties can begin to accumulate if the information is not promptly removed. A gag order against the Romanian Centre for Investigative Journalism in December 2018 came into effect in January 2019, and since 30 July 2019 it has been accruing fines at a rate of about €200 per day for not removing certain Football Leaks’ stories. The gag order was filed in parallel with a civil suit, which is still pending.

Meanwhile, data protection law has also been abused to intimidate journalists and to force them to reveal their sources. In 2018, the investigative news site RISE Project received a letter from the Data Protection Agency, threatening to fine it €20 million if it failed to reveal its sources for the personal data contained in a series of articles.

The constitution states that freedom of expression may not prejudice individuals’ dignity, honour, privacy or the right to their own image. It also protects the secrecy of correspondence.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113687″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Slovakia”][vc_column_text]

Slovakia

Criminal defamation is punishable with up to two years imprisonment or, in extreme cases, up to eight years. Although complaints of criminal defamation were quite rare until recently, media lawyer Tomáš Langer says that they seem to be becoming increasingly common.

Most actions are taken under the civil code, which protects the individual’s personal rights, including honour, human dignity, privacy, name and expressions of a personal nature. The law provides for an individual to demand compensation, which is decided by the court while taking into account the seriousness of the harm and any unlawful interferences with the individual’s rights. Research published by the IPI in 2017 found that the compensation awarded in the majority of cases was €10,000 or less, although it may reach up to €20,000.

The time and costs associated with defending a lawsuit are a significant drain on media outlets, as it can take up to 10 years for a legal action to be concluded. Most lawsuits are filed against publications (rather than individual authors), but there are exceptions. Concerns have been raised in the past over the litigiousness of the Slovak judiciary, as well as the objectivity of their fellow judges given their frequent successes.

Data protection law has also been used to try to intimidate journalists, with the Slovak data protection authority sending a letter to the Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism threatening to impose a fine of up to €10 million if it did not disclose its sources.

The Slovak press code was amended last year to grant politicians the right to reply to media content when they allege their dignity, honour, or privacy to have been violated by false statements of facts. If a media outlet fails to publish a reply, it can be fined up to nearly €5,000. The code requires that a request for reply must be sent to the publisher before an action on publication of reply can be filed to the court. However, politicians often decide to immediately file a civil lawsuit on protection of personal rights without applying for a reply.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113689″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Slovenia”][vc_column_text]

Slovenia

Insult, defamation, slander, calumny and malicious false accusation of crime are all criminal offences, punishable with a fine of up to two years in prison. In practice, journalists are usually subject to suspended sentences or fines. Misuse of personal information, publication of private documents (diaries, letters or other private writings), unwarranted audio recording and unjustified image recording are punishable with a fine or up to a year in prison.

Civil action is more commonly used against the media, however, with action usually being taken under the civil code. Compensation may be awarded in cases where there has been an infringement of a personal right. It provides for monetary compensation for defamation of reputation even if there has been no material damage. Future immaterial damage may also be taken into account. Damages awarded usually range from €5,000 to €20,000, but may be more in extreme cases. According to media lawyer Jasna Zakonjšek, almost every decision in the area of media law is based on ECtHR case law.

The right to reply, privacy of correspondence and the protection of personal data are all guaranteed under the Slovenian constitution. Under the Mass Media Act, the right to reply allows not only for the correction of factual errors but also for “other or contradictory facts and circumstances” to be published. The media must publish or broadcast the unamended response either within 48 hours of receipt or in the next issue or episode.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113691″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Spain”][vc_column_text]

Spain

Both civil and criminal law are used to make legal threats and bring legal action against journalists in Spain. Criminal charges are filed against journalists for defamation and revelation of secrets, punishable with imprisonment of up to two and five years respectively. No journalists have been imprisoned on these charges in recent years, however. According to the IPI, vexatious criminal charges do reach the courts, but the majority of them are dismissed.

Civil defamation claims are brought under the 1982 Protection of Honour, Privacy and Right to a Respectful Image Law. There is no limit to the non-pecuniary damages that may be awarded. The 1982 law and the 1966 Press and Printing Law are referred to in a 2014 report by the Open Society Foundations as being “designed to protect any person who may feel offended by the truth”. Although the 1966 law has not been formally repealed, it has not been used since Spain’s transition to democracy in 1978.

According to media expert Joan Barata, the Constitutional and Supreme Courts’ case law – the most important reference for domestic courts – tends to align itself with that of the ECtHR, although there are exceptions, particularly regarding criminal cases. He says that case law from both courts has been becoming more closely aligned to ECtHR jurisprudence in recent years.

The right-of-reply process stipulates that anyone directly affected by publication of incorrect or damaging information may require the media outlet to publish a corrected version, without comment and with the same prominence as the original. Failure to comply can invoke court action to determine what sort of correction is appropriate. The right to honour, personal and family privacy and self-image are guaranteed by the constitution.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113693″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Sweden”][vc_column_text]

Sweden

The Freedom of the Press Act, one of four fundamental laws that makes up the Swedish constitution, states that no one may be prosecuted, held liable under criminal law or held liable for damages on account of an offence other than as prescribed in the cases specified in that act. The offences listed in the act include carelessness with secret information, treason and defamation.

Defamation, aggravated defamation and insult are criminal offences, punishable with fines or up to two years in prison. If the defamatory statement is found to be true or justifiable, the defendant is not held responsible. Liability for an offence lies with the responsible editor at the time of publication. The Freedom of the Press Act also provides for private claims for damages to be pursued on the basis of those offences.

In practice, due to the extensive constitutional protections afforded to the media, it is rare for legal action to be brought against a news outlet, much less for the complaint to result in a conviction. Complaints are usually made to the Media Ombudsman or the Swedish Press and Broadcasting Authority.

There is no statutory right of reply, but it exists de facto as a result of established practice under the Freedom of the Press Act and the operation of the Media Ombudsman and the Swedish Council for Media Ethics. In case of a code breach, the council requires the media outlet to publish (or broadcast) its decision and to pay an administrative fee.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113695″ img_size=”full” el_id=”United Kingdom”][vc_column_text]

United Kingdom

Legal threats and actions remain a serious threat to journalism throughout the UK, but the nature of the threats and actions differ significantly depending on the jurisdiction. Defamation is most commonly used; although it has been decriminalised throughout the UK, the law is not the same in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

England and Wales

In England and Wales, the Defamation Act 2013 has helped stem the flow of lawsuits by introducing a “serious harm” threshold and placing restrictions upon the types of cases that can be brought to court there. Although the act provides for truth and public interest defences, the burden of proof that is required from the publisher places an enormous, often impossible, burden on the media. The act provides that the author, editor or publisher may be liable for the offence.

A 2009 Reuters Institute report noted that “privacy actions have become the new libel”. Efforts are often made – sometimes successfully – to seek pre-publication injunctions under the Human Rights Act.

Although data protection provides certain protections for the media, it does not prevent individuals from filing subject access requests to news outlets, sometimes in an effort to intimidate journalists and prevent them from investigating the individual. Subject access requests can put a drain on small news outlets in particular. According to Pia Sarma, editorial legal director for Times Newspapers, data protection laws are now being used to protect reputation rather than personal data.

Scotland

In Scotland, defamation remains the most common route by which the media is legally challenged. According to the Scottish office of the National Union of Journalists, threats of legal action are far in excess of the actions being brought.

Defamation law is currently based mainly on common law, with some statutory provisions. A shortage of modern Scottish case law has resulted in Scottish courts and practitioners tending to follow decisions of the English courts and the ECtHR. A reform bill was introduced to the Scottish parliament in December 2019.

Northern Ireland

Defamation law, which is most commonly used to bring legal action against journalists in Northern Ireland, is determined by the Defamation Act 1955 and the Defamation Act 1996, alongside common law. Privacy law is also used, albeit less frequently. Northern Ireland judges have in the past cited public interest as a defence for the curtailment of the right to privacy.

According to media lawyer Olivia O’Kane, alleged terrorists have used libel and privacy actions in an effort to silence investigative journalists. Although their efforts have been unsuccessful, the battles have been “extremely costly and time-consuming”. In 2013, the then editor of the Belfast Telegraph was quoted in the House of Lords as having said that “I have edited newspapers in every country of the United Kingdom and the time and money now needed to fight off vexatious legal claims against us here is the highest I have ever experienced”.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”113700″ img_size=”full” el_id=”Annexes”][vc_column_text]

Annexes

Further reading

Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region: A Comparative Study: www.osce.org/fom/303181?download=true

Media Laws Database: http://legaldb.freemedia.at/

Freedom of Expression, Media Law and Defamation: www.mediadefence.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/MLDI.IPI%20defamation%20manual.English.pdf

Media Pluralism Monitor: https://cmpf.eui.eu/media-pluralism-monitor/

Glossary

CEPEJ European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice

ECtHR European Court of Human Rights

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation

IPI International Press Institute

OSCE Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe

SLAPP Strategic lawsuit against public participation

Right to reply (right to correction) The right to reply to or to defend oneself against public criticism in the same way in which the original criticism was published or broadcast. In some countries it is a legal or constitutional right, in other countries it is practised but not codified. In theory, the provision of a right to reply should help to prevent lawsuits from being brought against journalists and media outlets

Non-pecuniary Not consisting of money

Pecuniary Consisting of money

Tort A civil wrong (other than a breach of contract) causing harm for which compensation may be obtained in the form of damages or an injunction

Acknowledgements

Index on Censorship would like to thank the following lawyers, media experts and association representatives for their contributions and feedback:

Vesna Alaburić, Croatian lawyer; Joan Barata, media law expert; Paško Bilić, Institute for Development and International Relations (Croatia); Linda Bīriņa, Latvian lawyer; Seweryn Blumsztajn and Krzysztof Bobinski, Society of Journalists (Poland); Justin Borg Barthet, University of Aberdeen; Bea Bodrogi, Hungarian lawyer; Vibeke Borberg, Danish lawyer; Linde Bryk, Amsterdam Law Clinics; Tove Carlen, Swedish Union of Journalists; Helena Chaloupková, Czech lawyer; Maria Cheresheva, AEJ-Bulgaria; Luc Caregari, Luxembourg Union of Journalists; Pol Deltour and Charlotte Michils, Flemish/Belgian Association of Journalists; Danka Derifaj and Hrvoje Zovko, Croatian Association of Journalists; Zsuzsa Detrekői, Hungarian lawyer; Palatics Edit, Hungarian lawyer; Achilles Emilianides, University of Nicosia; Kristine Foss, Norwegian Press Association; Liana Ganea, ActiveWatch Romania; Kalia Georgiou, Cypriot lawyer; Ralph Oliver Graef, German lawyer; Jan Hegemann, German lawyer; Charlie Holt, Greenpeace International; William Horsley, Centre for Freedom of the Media (UK); Theo Jordahl, Norwegian lawyer; Michael Kealey, Irish lawyer; Sarah Kieran, Irish Lawyer; Michal Klima, Czech branch of the IPI; Päivi Korpisaari, University of Helsinki; Yannis Kotsifos, ESIEMTH (Greece); Tomáš Langer, Slovak lawyer; Ann-Marie Lenihan, NewsBrands Ireland; Andrea Martin, Irish lawyer; Estelle Massé, Access Now; Roger Mann, German lawyer; Stratis Mavraganis, Greek lawyer; Tarlach McGonagle, Leiden Law School; Nick McGowan-Lowe, NUJ Scotland; Ingrida Milkaitė, Ghent University; Daniel Moßbrucker, University of Hamburg; Nicola Namdjou, Global Witness; Antonella Napoli, Articolo 21; Tomáš Němeček, Czech lawyer; Ants Nomper, Estonian lawyer; Nelly Ognyanova, Sofia University; Olivia O’Kane, Northern Ireland lawyer; Konrad Orlik, Polish lawyer; Gill Phillips, The Guardian News and Media; George Pleios, University of Athens; Pia Sarma, Times Newspapers; Konrad Siemaszko, Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (Poland); Andrej Školkay, The School of Communication and Media; Alberto Spampinato, Ossigeno per l’Informazione; Ivana Stigleitner Gotovac, Croatian lawyer; Francisco Teixieira da Mota, Portuguese lawyer; Helle Tiikmaa, Estonian Association of Journalists; Emmanuel Tordjman, French lawyer; Karmen Turk, Estonian lawyer; Paola Rosà, OBCT (Italy); Dori Ralli, ESIEA (Greece); Jens van den Brink, Dutch lawyer; Tess van der Linden, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen; Caro Van Wichelen, Belgian lawyer; Giulio Vasaturo, Sapienza University of Rome; Dirk Voorhoof, media law expert; Jon Wessel-Aas, Norwegian lawyer; Jasna Zakonjšek, Slovenian lawyer.

Photo credits

Chip Somodevilla/Getty (main image), fcangia (Austria), Reine-Marie Grard (Belgium), Jim Black (Bulgaria), Ivan Ivankovic (Croatia), Dimitris Vetsikas (Cyprus), Markéta Machová (Czech Republic), Thomas Wolter (Denmark), NolensVolens (Estonia), Tapio Haaja (Finland), Walkerssk (France), Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke (Germany), Panagiotis Lianos (Greece), Alexey Mikhaylov (Hungary), Larahcv (Ireland), Nikolaus Bader (Latvia), Evgeni Tcherkasski (Lithuania), Pit Karges (Luxembourg), Sofia Arkestål (Malta), Николай Начев (Netherlands), André Neufeld (Norway), Rudy and Peter Skitterians (Poland), Granito (Portugal), Arvid Olson (Romania), Momentmal (Slovakia), Vilva Roosioks (Slovenia), cerqueiraricardo (Spain), Ioannis Ioannidis (Sweden), luxstorm (UK)[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”113711″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://postkodstiftelsen.se/en/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]This report has been supported by the Swedish Postcode Foundation. The foundation is a beneficiary to the Swedish Postcode Lottery and provides support to projects that foster positive social impact or search for long-term solutions to global challenges. Since 2007, the foundation has distributed over 1.5 billion SEK in support of more than 600 projects in Sweden and internationally.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

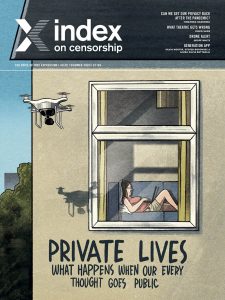

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine