26 Oct 2015 | About Index, Events

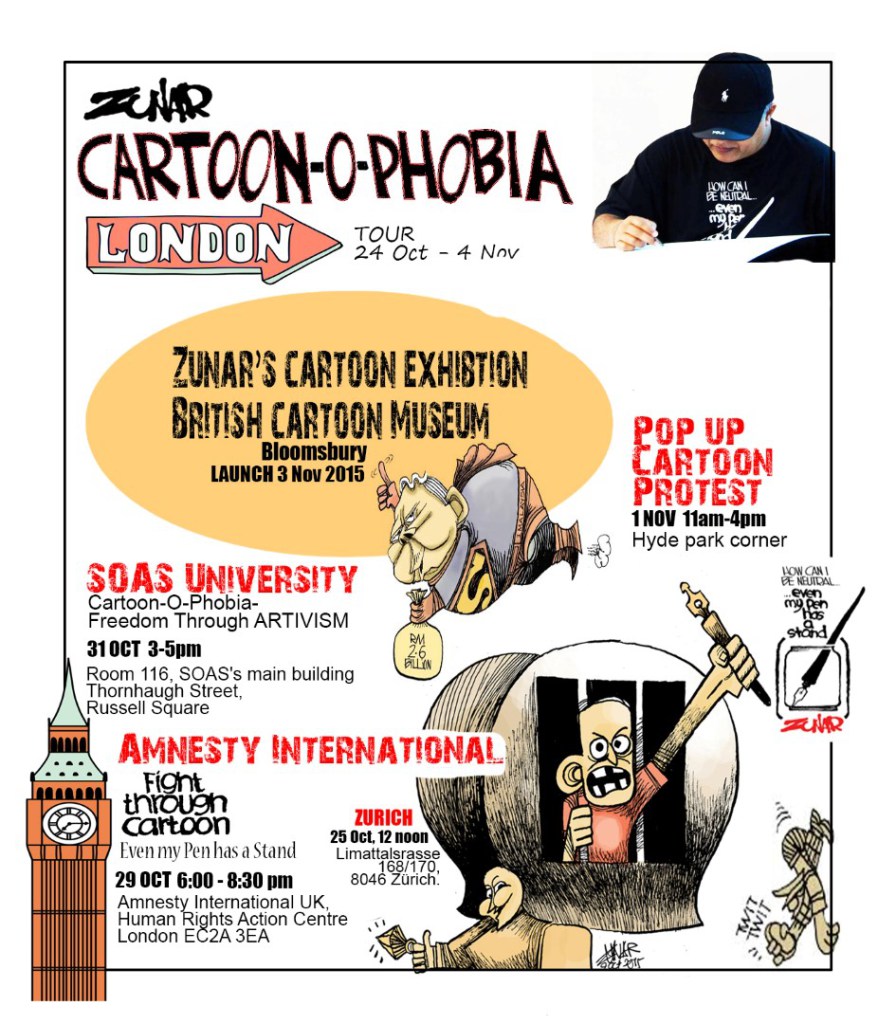

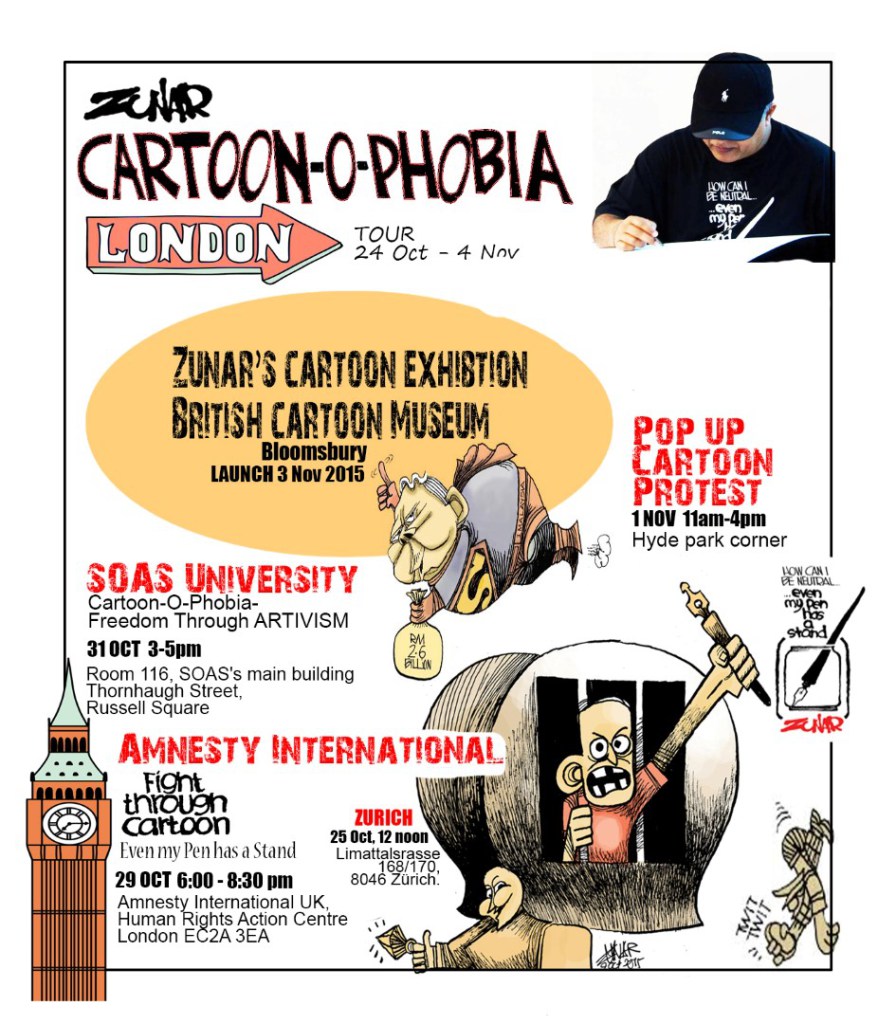

Zunar is a Malaysian political cartoonist who has been repeatedly targeted by authorities on account of his work.

Five of his cartoon books have been banned by the Malaysian government for allegedly carrying content “detrimental to public order” and thousands confiscated in an effort to curtail freedom of expression.

On the eve of his trial, and facing a maximum penalty of 43 years imprisonment, Zunar is coming to the UK to exhibit a small selection of his work at the Cartoon Museum.

Join us to hear a courageous artist speak about his cartoons and his inspirations, and human rights and freedom of expression in his home country Malaysia.

The evening will include film, a talk and Q&A from Zunar, and a chance to draw your own cartoon, with tips from Zunar himself – telling the Malaysian authorities to drop all charges against a man who might otherwise spend the rest of his life in jail.

When: Thursday, 29 Oct, 2015, 6pm – 8:30pm

Where: Amnesty International UK, Human Rights Action Centre, London, EC2A 3EA (map)

Tickets: Free, but registration required

6:00pm – Arrival

6:15pm – Documentary screening

6:45pm – Introductions

7:00pm – Zunar talk and Q&A

8:00pm – Draw your own cartoons with tips from Zunar

This event is being co-hosted by Amnesty International UK, Index on Censorship and SUARAM.

23 Oct 2015 | mobile, News and features, Youth Board

Artist collective HAD and their memorial for the victims of Srebrenica genocide. (Photo: Ilhana Babić)

This month, the Index Youth Advisory Board members were asked to write a blog post exploring their opinions on censorship in the arts by citing a case.

Lejla Becar: Memorial to victims of Srebrenica massacre

In the small town Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, a square was opened on 5 October to commemorate the victims of Srebrenica genocide. The construction of the square has since been in the spotlight as a large number of citizens disapproved of it being built, seeing it as overpriced and unnecessary.

Local artist collective HAD, made up of Muhamed Hamo Bešlagić, Anel Lepić and Damir Sarač, decided to contribute to keeping the memory of the victims alive. They decorated a 35-meter long wall nearby the square with images of war victims, focusing on Srebrenica genocide victims. They went to the authorities and suggested their work, which they named Silence, and it was approved. The three of them, an architecture student, a painter and a street artist, chose to work for free, feeling the moral obligation to keep the memory of the victims alive for future generations.

Once they started working on carving the images into the wall, they faced objections from their fellow citizens. People were disgusted with what they saw, and many approached the artists while they were working, expressing their disapproval of having such images shoved in their faces.

The accusations continue, however HAD continue with their work. They said: “Every quality artwork has to have negative critiques and negative comments. We somehow maybe even prefer the negative ones, they often show a deeper understanding of the work, they show that people pondered deeply. Indifference is absent when it comes to Silence. Everybody has some kind of reaction. That was one of our goals — to make the images speak for themselves by remaining completely silent.”

Twenty years after the war it seems people still don’t want to face what happened. Many look the other way, people say they remember when all they want to do is forget. HAD decided that Srebrenica genocide will not be remembered only on 11 July and they carved their decision in a concrete wall. Showing the true power of art.

Simeon Gready: #RememberMarikana graffiti

16 August 2015 marked the third anniversary of the Marikana massacre in South Africa, a day of remembrance in honour of the striking miners that lost their lives through lethal force by security forces in the country. It was an incident that reverberated worldwide and represented a black mark on South Africa’s progress as a democracy and a tragic consequence of the country’s increasingly rampant inequality.

Three years on, there is still no justice for the victims of the massacre, a group of anonymous artists under the banner of Tokolos Stencil Collective claimed responsibility for a series of graffiti and stencil statements on the campus of the University of Cape Town (UCT), indicating the University for its complicity in the massacre.

Statements such as “#RememberMarikana”, “non-poor only”, and “Max Price [UCT’s vice-chancellor] For Black Lives”, were framed as a form of protest against UCT’s investment in Lonmin, the mining company that owned the mine at which the massacre took place. Furthermore, it raised attention to the fact that judge Ian Farlam sits on the UCT Council while heading up the Marikana commission, the committee tasked with the official inquiry into the killings. His position and UCT’s investments are seen as a direct conflict of interest.

The university was quick to condemn the graffiti as an “irresponsible and inappropriate method of protest,” and many of the statements were removed within a week.

However, this was not enough to quell the discontent among the students. Despite the condemnation and removal, the graffiti exposed UCT’s investments in Lonmin and, as such, their association with South Africa’s darkest post-apartheid day.

Graffiti, in this manner, constitutes an appropriate and effective form of art and of protest. It is a tool through which the Tokolos Stencil Collective were able to express their right to freedom of expression and represent the dissatisfaction of the students with the actions of the university.

Harsh Ghildiyal: Agnes of God

In the late 1970s, Maureen Murphy was found bleeding in her room, with a wastebasket near her that contained a dead baby, asphyxiated. Sister Maureen Murphy, who was a nun, denied giving birth and stated that she didn’t remember being pregnant. There was a trial, and she was found not guilty of all charges by reason of insanity.

This incident bears similarities to a play (which also opened on Broadway in 1982), Agnes of God, that portrays a pregnant nun contending that the child was the result of a virgin conception (immaculate conception), followed by an investigation, with the play focusing on exchanges between the nun in charge of the convent and a psychiatrist. The play did not attract any criticism, even after it had been made into a film and was shown all over the world. Over two decades ago, the play was performed in Mumbai, India, too, and was very successful. There were no objections.

An adaptation of the Broadway play was set to premiere in Mumbai on the 4 October 2015 but on the 30 September, the director of the play tweeted that the show was canceled, citing threats of arrest, imprisonment, harm to body and property as reasons behind the decision. The Catholics Bishops Conference of India and Catholic Secular Forum contended that it is a wrongful portrayal of the character of clergy and hurts religious sentiments, and jointly sought a ban on the play.

This move to get the play banned can perhaps be attributed to the increasing number of intolerant people impatiently waiting to be offended, coupled with the ease of getting things banned in India (be it on religious or moral grounds). The increasingly intolerant society is proving to be a major hindrance to the freedom of expression of individuals in India. I would like to end by quoting a few sentences from Justice Chinnappa Reddy’s judgment in a case concerning expulsion of children who were Jehovah’s Witnesses on the grounds that they refused to sing the national anthem: “Our tradition teaches tolerance; our philosophy preaches tolerance; our Constitution practises tolerance; let us not dilute it.”

Matthew Brown: Isis Threaten Sylvania

In commenting on the decision to remove artwork from the Passion for Freedom art festival in London, I have rarely seen such an inexplicable and frankly ludicrous example of censorship in modern-day Britain.

The work in question, Isis Threaten Sylvania by artist Mimsy, is a satirical swipe at Isis and consists of seven scenarios featuring children’s toys as the Sylvanian Families. Depicting toy mice — or MICE-IS — it has been branded as “potentially inflammatory content”. The “contentious” point which has caused the hysterical reaction has been that in the backdrop to each scene, with the mice waving black flags and plotting to disturb the tranquil world of Sylvanian Families.

Perhaps the most farcical aspect of this entire story is that the artwork was due to be exhibited at an event specifically designed to reflect the full spectrum of artistic expression. The exhibition is designed specifically to give artists an opportunity to be provocative, open debate and exercise their freedom of speech. For the police to intervene on the simple grounds that the work is “potentially” provoking isn’t just ludicrous, it is dangerous and raises important questions about the scope of police powers in the world of art.

When we reach a point that art depicting toy to depict a terrorist threat is considered too dangerous for public consumption, one has to wonder what we are really fighting for. If this artwork offends to the point it is banned, then what separates us from the other side? We are either defeated by the enemy or we censor ourselves in this hysterical rush to prevent the potential of offending anyone.

Tom Carter: Isis Threaten Sylvania

After the board took the decision to remove artwork from the exhibition after facing a £36,000 security bill for the six day show.

Satire through art is meant to be humorous, but it has a purpose beyond this, often constructing genuine social criticism. If, due to the threat of intimidation and violence, individuals and organisations feel unable to express themselves then the notion of freedom of expression has very little meaning.

Mimsy, stated her motivation behind the work was to use Sylvanian characters, such as cats and koalas, to show criticism of radical Islam is nothing to do with race, telling the Guardian: “I’m sick and tired of people calling criticism of fanatical Islam racist, because racism is about your skin colour and radical Islam is nothing to do with that. There are millions of Muslims who are shocked by it too.”

Art has a key place in our democracy in creating social criticism and generating political thought in individuals. It is interesting that a country which puts large amounts of public money into actively promoting art forms that would have a much smaller presence if left to the market is unwilling to put money into protecting its population’s right to express itself freely. Artists must be free to criticise and satirise religious extremists.

19 Oct 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, Counter Terrorism, mobile, Statements

In its new extremism strategy, the government is proposing measures that will criminalise legitimate speech and shrink the space for open debate throughout society. There is already a wealth of legislation that deals with criminal offences, including the Terrorism Act and the Public Order Act, and there is no need for new laws that will seriously harm everyone’s right to freedom of expression in this country.

“We are concerned that the extremism strategy outlined this morning has the potential to massively damage the reputation of the British educational establishment – universities in particular which should be the home of debate and academic academic inquiry. This will have the effect of ramping up a climate of fear where both lecturers and students are afraid to speak,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship.

“The government has created an impossible bind for itself: in the name of protecting our values, it’s now seeking to undermine the most fundamental value of all for democracy – freedom of expression. This is a deeply misguided policy that will not only stigmatise minorities, it will criminalise political speech across society and introduce a culture of caution,” said Jo Glanville, director, English PEN.

The government’s counter-terrorism policy is already having a chilling effect on freedom of expression. Over the past six months, a series of incidents across society indicates that arts and educational institutions are censoring and self-censoring in the mistaken belief that any exploration or discussion of extremism is or may be illegal.

This includes the cancellation of the National Youth Theatre’s production of the play Homegrown, the banning of a Mimsy art work at the Mall Galleries that satirised Isis and the questioning of a school child who discussed ecoterrorism in class.

The space for political speech and artistic expression is rapidly diminishing.

19 Oct 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, mobile, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

With UK-China relations warming, the president of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, will pay a state visit to the UK from 20-23 October. The UK government hopes the visit will help finalise multibillion-pound deals for Chinese state-owned companies to contribute to the building of two British nuclear power plants.

Many — including the Dalai Lama — are concerned that Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne are putting the desire for profit above concern for human rights.

Xi may be staying in luxury at Buckingham Palace during his visit, but here are just five examples of how respect for free speech in China doesn’t get past the front door:

1. Locking up artists

The soccer-loving Chinese president is due to visit Manchester City Football Club’s stadium with Cameron during his visit. But will he make time for the new exhibition by Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei in London? We won’t hold our breath.

The major retrospective of the artist’s work is currently on show at the Royal Academy of Arts. Ai — whose work is famous for addressing human rights abuses and corruption — has been harassed, beaten, placed under house arrest and imprisoned.

The current London exhibition almost didn’t go ahead as the British Embassy in Beijing turned down Ai’s request for a business visa in connection with his criminal conviction for tax fraud — an accusation he denies. British Home Secretary Theresa May eventually overturned the embassy’s decision, but only after a mass public outcry. This shouldn’t be the height of the British government’s efforts to address Chinese human rights abuses.

2. The use of online “opinion monitors”

China’s Terracotta Army, the 8,000-strong force of sculptures depicting warriors and horses, was purpose-built to protect emperor Qin Shi Huang, who died in 210 BC, in his afterlife. In the modern day, China’s army of “opinion monitors”, which has been purpose-built to protect China’s current leaders from criticism and dissent, dwarfs anything the Qin dynasty could muster.

Last year, Index on Censorship reported that the Chinese government is expanding its censorship and monitoring of web activity with a new training programme for an estimated two million flies on the firewall.

China’s hundreds of millions of web users increasingly use blogs to condemn the state, but posts are routinely deleted by government employees. In 2012, monitors banned more than 100 search terms relating to the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protest of 1989 and even shut down Google services.

3. Banning books

Often overshadowed by China’s internet censorship, we shouldn’t forget that Chinese authorities have a rich history of restricting free expression in literature. In 1931, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was banned for its portrayal of anthropomorphised animals for fear children would regard humans and animals as equal. During Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, all aspects of arts and culture had to promote and aid the revolution. Libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed and books deemed undesirable were burned.

The country’s post-Mao transition has been marked by a commitment to “modernising”. While the Chinese populace has access to more information than ever before, their leaders’ continuation of banning books on grounds of non-conformity and deviance are anything but modern.

Publications which are still banned — often for perceived politically incorrect content — include the memoirs of Li Rui, a retired Chinese politician and dissident who caused a stir in the CCP by calling for political reform; Lung Ying-tai’s Big River, Big Sea about the Chinese Civil War; and Jung Chang’s best-selling Wild Swans, a history that spans a century, recounting the lives of three female generations in the author’s family.

4. Detaining activists

Recent years have been marked with an intensification of the crackdown on dissent. On 6 March 2015, just days before International Women’s Day, the Chinese government detained a number of high-profile feminist activists. They were accused of creating a disturbance and, if convicted, could have received three-year prison sentences.

The women had been linked to several actions over the years which highlight issues such as domestic violence and the poor provision of women’s toilets, obvious embarrassments to the authorities.

As a result of their detention, China’s small, but increasingly vocal feminist movement was dealt a heavy blow. Demonstrations were cancelled and debate was effectively silenced. Five of the activists were released fairly quickly, but five more were in prison until 13 April, with two being denied treatment for serious medical conditions while in custody.

5. Repressing Uyghur Muslims

China continues to persecute the largely Muslim minority Uyghurs of Xinjiang. A tough system of policies and regulations deny Uyghurs religious freedom and by extension freedom of expression, association and assembly.

The abuse of national security and anti-terror laws to persecute Uyghurs and further deny them freedom of expression was highlighted in the recent ban by the Chinese authorities on 22 Muslim names in Xinjiang in an apparent attempt to discourage extremism among the region’s Uyghur residents. Many children were barred from attending school unless their names were changed.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant online editor at Index on Censorship