4 May 2020 | India, News and features

Image by Raam Gottimukkala from Pixabay

A friend in the police department apologetically texted me with some “friendly” advice. “Don’t be extra active on social media over corona issues which may lead to panic and rumours. There may be legal issues over it,” he said.

He wouldn’t elaborate further, but it didn’t take much to understand. A freelance journalist was arrested in Andaman and Nicobar Islands for a tweet on a bizarre quarantine rule. At least 13 people from various walks of life have been arrested since 1 April in Manipur for Facebook posts. A doctor at a government hospital had been harassed by the police and questioned for 16 hours at a police station after he put up a Facebook post complaining about the lack of protection gear for doctors. A founder of an online publication was arrested in Tamil Nadu for reports on problems faced by government healthcare workers. In Chhattisgarh, a journalist was slapped with a notice threatening arrest for his report on the plight of women in lockdown.

The pandemic has given the government free rein. India is witnessing very high levels of suppression of free speech and media censorship across the country.

“Everything is censored,” said a Kolkata-based journalist, declining to be identified. “You cannot report on anything that is not confirmed by the government. Getting data on anything is an ordeal.”

In the name of curtailing rumours and fake news, there have been curbs on free speech and freedom of journalists to cover the pandemic, especially those with questions that make the government uncomfortable. “It’s as if the media is an opponent. It is as if asking questions of the government is a crime, or a politically motivated exercise,” said the journalist.

On 30 March, Scroll.in published a list of ten questions that health beat reporters in Delhi had for the central government but did not get any answers. These included: How did the Indian government arrive at the pricing of the Covid test in private labs, which is Rs 4,500 ($60), and among the highest in the world? Why has the drug controller not released the list of Covid-19 testing kits that have been granted import and manufacturing licences? What are the steps the government is taking to map the scale of Covid-19 outbreak in the community? What arrangements have been made to ensure patients living with life-threatening conditions like cancer, tuberculosis and HIV that require continuous support are not deprived of critical care?

While questions such as these remain unanswered, journalists covering the Covid crisis say they are witnessing unprecedented levels of censorship. Government interaction with the press is stressed. Prime Minister Modi, in keeping with his record, has not organised a single press conference on the issue. Harsha Vardhan, a health minister, has interacted infrequently with the press, while the daily press briefings are conducted by a senior bureaucrat in the health department, Lav Agarwal.

“In the ministry’s organisation structure,” writes Vidya Krishnan in Caravan magazine, “Agarwal comes after two secretaries, four special secretaries and four additional secretaries, and is one of the thirteen joint secretaries in the ministry of health.”

Even the press briefings are not for all journalists. Barring Doordarshan (DD), India’s public broadcaster, and news agency Asian News International and a few accredited journalists, others have been barred from attending the press briefings in the name of social distancing. “The directive on social distancing became an excuse to not have journalists in the room,” said Anoo Bhuyan, Delhi-based health reporter with Indiaspend, a data journalism-based news portal.

“Then we got a message one day saying other than ANI and DD no one needs to attend the press conference. They said we could send our questions through WhatsApp. However, there is no guarantee that your question will be picked to be answered by Mr Agarwal. It is like a lucky draw without any rationale and definitely does not give equal chances to all journalists. In the very short time allotted for questions, only two to four questions are picked up, some of which are repetitions.”

The Modi-led government even approached India’s Supreme Court to legalise censorship by seeking an order that would prevent the media to publish anything “without ascertaining the true factual position” from the government. The court did not go that far, only directing the media to “refer to and publish the official version about developments”.

“The order itself does not have teeth, but the fact that there is an order may freak out many,” said Bhuyan. “It gets diabolical in that Lav Agarwal makes it a point to sometimes refer to the order and ‘remind’ journalists to ‘exercise caution’ and ‘report responsibly’.”

“What’s happening in India is extremely disturbing,” Vidya Krishnan, a Goa-based health reporter with Caravan magazine, tweeted on April 1. There is a media gag in place, doctors have been threatened to not speak out against lack of PPE kits, and the health ministry says we have no local transmission (without scaling up testing). Genuinely struggling to understand how we can continue reporting in this Orwellian setting.”

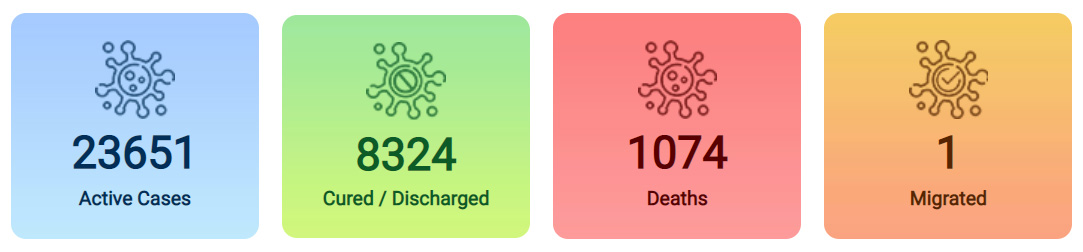

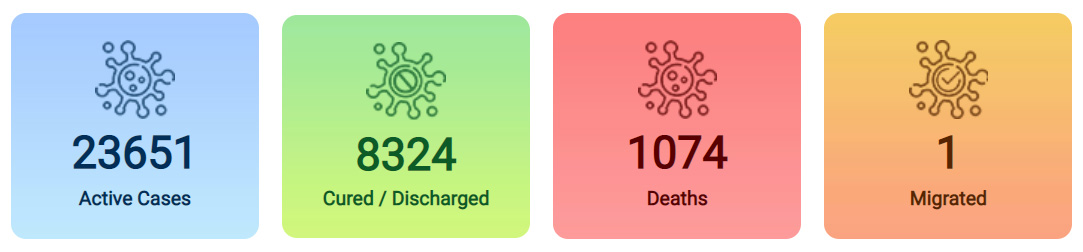

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, data correct as at 30/4/2020

Meanwhile, Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of the Indian state of West Bengal, announced insurance cover for journalists covering Covid from the frontlines. It is a combination of medical and life cover worth 10 hundred thousand Indian rupees (£10,500). There’s one rider: journalists have to do “positive” stories. “People are depressed seeing negative news all the time,” she said. “Journalists should be involved with the government,” she added without leaving anything to doubt.

This came just two days after she threatened legal action against journalists if they report “unconfirmed” fatality figures. Banerjee, who has a record of booking journalists, academics and the general public for social media posts critical of her, faces allegations that she is supressing Covid-related data in the state. The state has a special committee to “audit” and “ascertain” Covid deaths.

Banerjee has asked journalists to “behave properly” or face legal action.

1 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

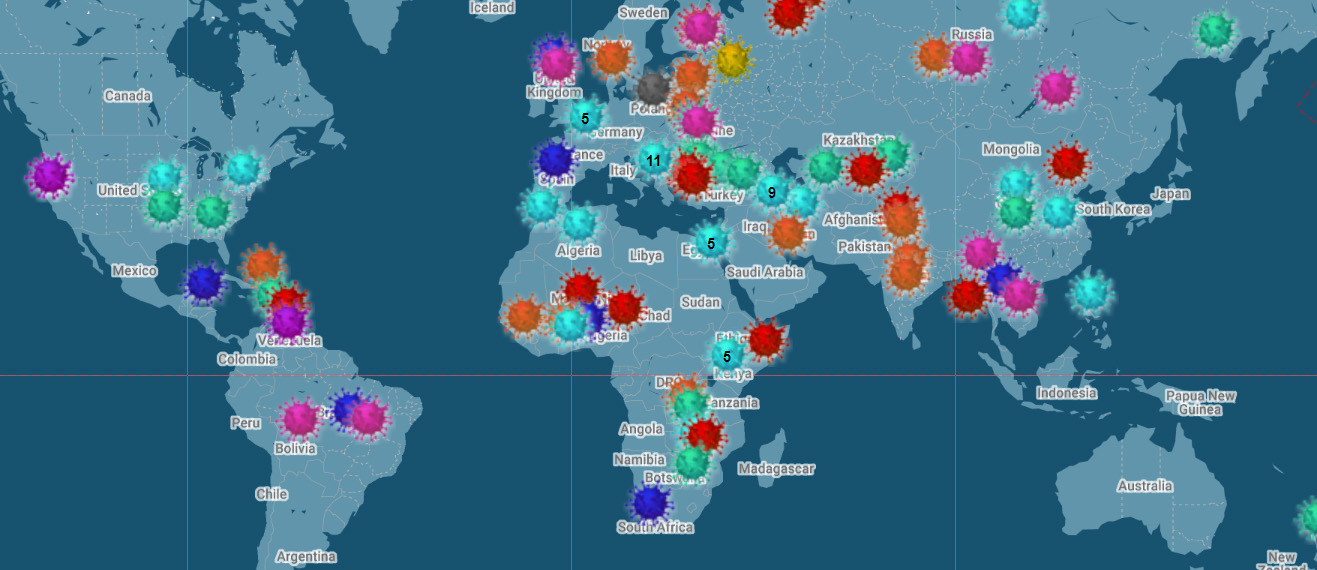

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Apr 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”As China struggles with coronavirus, will there be any change in the attempts it makes to get international companies to censor their content before operating within its borders, Charlotte Middlehurst reports” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”113104″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The legacy of the coronavirus in the country where it all began is likely to continue long after the virus itself has been dealt with. The Chinese government may have seen some pushback from its citizens on how it initially managed information surrounding the outbreak, but at the end of the crisis it might find itself with even more control over how information is disseminated within its borders.

“Beijing is trying to balance a tightening of social control in the interest of public health, and a loosening of social control to promote economic growth. Loosening social control means encouraging companies and people to go back to work,” said William Callahan, a professor of international relations at LSE.

“However, China is unlikely to loosen its control over censorship – even for international companies like Apple – to promote economic activity.

“From what we’ve seen, Beijing is using the coronavirus crisis to build and enforce a more intense surveillance and control regime. This goes beyond censorship to produce and promote ‘positive news’ about China’s efforts to fight the pandemic, alongside ‘negative news’ that criticises how Italy, the USA and other countries deal with it.”

Aynne Kokos, assistant professor at the department of media studies, University of Virginia, said: “I think there will be a slight loosening of inbound investment restrictions to support economic recovery. However, all indications suggest that the information environment will actually be more tightly controlled.”

“Whether or not the coronavirus dents China’s image depends on how successfully other countries respond as well as what happens when people in China return to work,” she said

Christina Maags, lecturer in Chinese politics at SOAS, University of London, said:

“While the Chinese economy is suffering losses, it is also multi-national companies like Apple who are eager to find a quick solution so as to stop the delay in production and resulting negative impact on supply chains worldwide. Therefore, I think Xi and multinational companies both have interests in “reviving” the Chinese economy.”

The world can only wait to see whether China will be more desperate to encourage economic activity after the coronavirus outbreak, or things stay the same. However, the importance that the authorities have placed on managing the message has led to dozens of prominent brands issuing public apologies in China over recent years, a sign of how powerful the Chinese government has become. Household names incurring the wrath of the Chinese authorities range from Disney, for featuring a Tibetan monk in an animation (the screenwriter later changed the character to a white woman after acknowledging the company “risked alienating a billion people” who did not recognise Tibet as a place), to gaming group Red Candle, which included artwork comparing President Xi Jinping with Winnie the Pooh in one of its games (Xi is known to take offence to such comparisons). Meanwhile, catwalk brands Versace and Givenchy felt the need to say sorry for recognising Taiwan as a country.

China’s influence over foreign companies seeking access to its consumer market has been growing over the past few years. But those who trade freedom for profit risk reputational damage among consumers who care about the consequences of reneging on free speech.

“The Chinese government has become more aggressive in getting foreign companies to comply with whatever foreign demands they have and silencing people,” said Yaqiu Wang, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. “By caving into the Chinese demands you are putting your values [aside] – social responsibility, freedom. It is really corrosive. You are affecting the global freedom of speech.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” size=”xl”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The world can only wait to see whether China will be more desperate to encourage economic activity after the coronavirus outbreak, or things stay the same” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Companies that comply with Chinese demands risk setting dangerous precedents and they make it easier for other national leaders to exact similar demands. Apple, which has come under fire for supporting the Chinese government during the Hong Kong protests, has recently been criticised in India after censoring its local Apple TV programmes, just as freedom of speech and assembly is being threatened under Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

During the coronavirus outbreak China has been doubling down on its censorship of online forums as it seeks to control narratives around the disease. On 31 December, a day after doctors tried to warn the public about the then unknown virus, YY, a live-streaming platform, added 45 words to its blacklist, according to Citizen Lab. WeChat, a messaging app with a billion users, also censored coronavirus-related content.

Censored material included references to Li Wenliang, a doctor who had been silenced by police for trying to warn about theoutbreak, and neutral references to efforts on handling the outbreak.

The death of Li started a digital uprising (#WeWantFreedomOfSpeech), with people calling for online censorship to be lifted.

Kevin Latham, senior lecturer in social anthropology at the SOAS, University of London, China Institute, said: “The narrative on censorship has shifted over the weeks a bit. At the beginning it was clear they were much more open and quicker to act publicly than with Sars in the past – they appeared to have learned that lesson.

“However, once the story about the death of Li Wenliang came out, that narrative was undermined to some degree.”

There is little reason to expect things to change, in other words.

What’s the story so far? Apple blocks more than 370 apps in China, according to Chinese security experts Great Fire, including the virtual proxy networks that allow people to vault over firewalls. The company has failed to lift restrictions despite renewed pressure arising during the pandemic. Its decision to block a map app used by protesters in Hong Kong, taken a few months before, was also called out by critics.

Apple chief executive Tim Cook has defended the decision as borne of legal necessity.

“We would obviously rather not remove the apps but, like we do in other countries, we follow the law wherever we do business,” he said in 2017. “We strongly believe participating in markets and bringing benefits to customers is in the best interest of the folks there and in other countries as well.”

Wang said: “They say they are simply complying with local laws when we all know what they really care about is market access.”

Apple is not the only tech company criticised for capitulation. Last year, Google tried to build its own filtered search engine for China but the idea was scrapped following an outcry from its employees.

Jeremy Daum, a senior research scholar at Yale Law School, says that while strict laws do exist, many statutes are written in a vague and sweeping manner, so it can be hard to know what the legal obligations really are. “In some cases it can be as vague as not publishing content that harms the nation’s interests,” he said.

Daum highlights the importance of distinguishing between enforced censorship and corporate acquiescence.

“Complicity sounds like they share a common goal of censorship, [but] the companies’ goals are profit, so they are not complicit in motive – It’s acquiescence,” he said.

The challenges to the power dynamic will centre on China’s influence to change content coming from beyond its borders. Apple TV has already issued guidelines to its programme makers to avoid criticism of China.

Ultimately, harming freedom of expression hits society’s most vulnerable, and those with the weakest voices, the most.

“Censorship isn’t just about politics,” said Karen Reilly, a community director at GreatFire.org, which tracks censorship in China.

“Censorship blocks people from reaching their communities and this is especially harmful to marginalised and young people. Online spaces are sources of support. If you grow up with censorship, your connection to your own culture may be cut off.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Additional research by Orna Herr and Adam Aiken

Charlotte Middlehurst is a London-based journalist specialising in Chinese current affairs. She tweets at @charmiddle

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

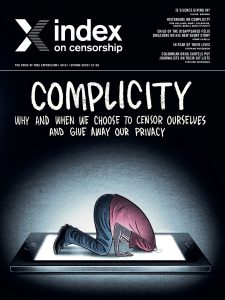

The piece is part of the 2020 spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Buy a copy or subscribe here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_column_text]The spring 2020 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how we are sometimes complicit in our own censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”112723″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ak Welsapar, Julian Baggini, Alison Flood, Jean-Paul Marthoz and Victoria Pavlova”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

In our In Focus section, we sit down with different generations of people from Turkey and China and discuss with them what they can and cannot talk about today compared to the past. We also look at how as world demand for cocaine grows, journalists in Colombia are increasingly under threat. Finally, is internet browsing biased against LBGTQ stories? A special Index investigation.

Our culture section contains an exclusive short story from Libyan writer Najwa Bin Shatwan about an author changing her story to people please, as well as stories from Argentina and Bangladesh.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Willingly watched by Noelle Mateer: Chinese people are installing their own video cameras as they believe losing privacy is a price they are willing to pay for enhanced safety

The big deal by Jean-Paul Marthoz: French journalists past and present have felt pressure to conform to the view of the tribe in their reporting

Don’t let them call the tune by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: A professor debates the moral questions about speaking at events sponsored by an organisation with links to the Chinese government

Chipping away at our privacy by Nathalie Rothschild: Swedes are having microchips inserted under their skin. What does that mean for their privacy?

There’s nothing wrong with being scared by Kirsten Han: As a journalist from Singapore grows up, her views on those who have self-censored change

How to ruin a good dinner party by Jemimah Steinfeld: We’re told not to discuss sex, politics and religion at the dinner table, but what happens to our free speech when we give in to that rule?

Sshh… No speaking out by Alison Flood: Historians Tom Holland, Mary Fulbrook, Serhii Plokhy and Daniel Beer discuss the people from the past who were guilty of complicity

Making foes out of friends by Steven Borowiec: North Korea’s grave human rights record is off the negotiation table in talks with South Korea. Why?

Nothing in life is free by Mark Frary: An investigation into how much information and privacy we are giving away on our phones

Not my turf by Jemimah Steinfeld: Helen Lewis argues that vitriol around the trans debate means only extreme voices are being heard

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: You’ve just signed away your freedom to dream in private

Driven towards the exit by Victoria Pavlova: As Bulgarian media is bought up by those with ties to the government, journalists are being forced out of the industry

Shadowing the golden age of Soviet censorship by Ak Welsapar: The Turkmen author discusses those who got in bed with the old regime, and what’s happening now

Silent majority by Stefano Pozzebon: A culture of fear has taken over Venezuela, where people are facing prison for being critical

Academically challenged by Kaya Genç: A Turkish academic who worried about publicly criticising the government hit a tipping point once her name was faked on a petition

Unhealthy market by Charlotte Middlehurst: As coronavirus affects China’s economy, will a weaker market mean international companies have more power to stand up for freedom of expression?

When silence is not enough by Julian Baggini: The philosopher ponders the dilemma of when you have to speak out and when it is OK not to[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Generations apart by Kaya Genç and Karoline Kan: We sat down with Turkish and Chinese families to hear whether things really are that different between the generations when it comes to free speech

Crossing the line by Stephen Woodman: Cartels trading in cocaine are taking violent action to stop journalists reporting on them

A slap in the face by Alessio Perrone: Meet the Italian journalist who has had to fight over 126 lawsuits all aimed at silencing her

Con (census) by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Turns out national censuses are controversial, especially in the countries where information is most tightly controlled

The documentary Bolsonaro doesn’t want made by Rachael Jolley: Brazil’s president has pulled the plug on funding for the TV series Transversais. Why? We speak to the director and publish extracts from its pitch

Queer erasure by Andy Lee Roth and April Anderson: Internet browsing can be biased against LGBTQ people, new exclusive research shows[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Up in smoke by Félix Bruzzone: A semi-autobiographical story from the son of two of Argentina’s disappeared

Between the gavel and the anvil by Najwa Bin Shatwan: A new short story about a Libyan author who starts changing her story to please neighbours

We could all disappear by Neamat Imam: The Bangladesh novelist on why his next book is about a famous writer who disappeared in the 1970s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Demand points of view by Orna Herr: A new Index initiative has allowed people to debate about all of the issues we’re otherwise avoiding[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Ticking the boxes by Jemimah Steinfeld: Voter turnout has never felt more important and has led to many new organisations setting out to encourage this. But they face many obstacles[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.