Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”5px”][vc_custom_heading text=”Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_empty_space height=”5px”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Winners of the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship receive 12 months of capacity building, coaching and strategic support. Through the fellowships, Index seeks to maximise the impact and sustainability of voices at the forefront of pushing back censorship worldwide.

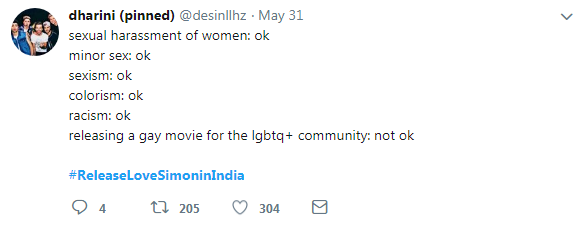

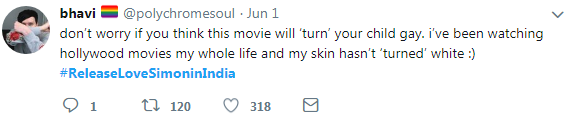

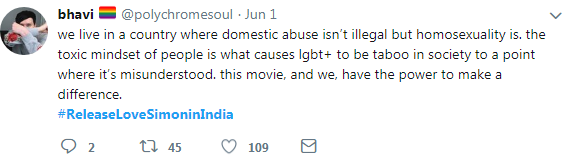

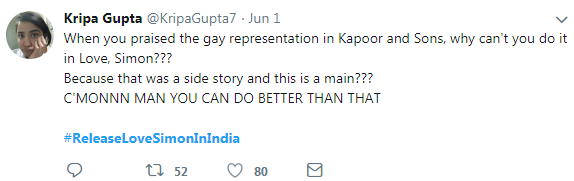

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/Qv66jpE3kuk” align=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” css=”.vc_custom_1504188991311{background-color: #f2f2f2 !important;}”][vc_column][vc_tta_tabs color=”white” active_section=”1″][vc_tta_section title=”2019 Fellows” tab_id=”1554816605919-419ceeb9-dbd4″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”2019 Fellows” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Selected from over 400 public nominations and a shortlist of 15, the 2019 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows exemplify courage in the face of censorship. Learn more about the fellowship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”Zehra Doğan” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2019%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”104529″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/04/arts-fellow-2019/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”CRNI” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F04%2Fcampaigning-fellow-2019%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”104518″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/04/campaigning-fellow-2019/”][vc_column_text]The 2019 Campaigning Award is supported by Mainframe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”Fundación Karisma” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F04%2Fdigital-activism-fellow-2019%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”104520″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/04/digital-activism-fellow-2019/”][vc_column_text]The 2019 Digital Activism Award is sponsored by Private Internet Access[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”Mimi Mefo” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F04%2Fjournalism-fellow-2019%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”104523″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/04/journalism-fellow-2019/”][vc_column_text]Sponsored by Daily Mail and General Trust, Daily Mirror, France Medias Monde, News UK, Telegraph Media Group, Society of Editors[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”2018 Fellows” tab_id=”1501506166658-bae3c112-ebd9″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”2018 Fellows” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Selected from over 400 public nominations and a shortlist of 16, the 2018 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows exemplify courage in the face of censorship. Learn more about the fellowship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Museum of Dissidence” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2018%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”97994″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/arts-fellow-2018/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”ECRF” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fcampaigning-fellow-2018%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”97988″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/campaigning-fellow-2018/”][vc_column_text]The 2018 Campaigning Award is supported by Doughty Street Chambers[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fdigital-activism-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Habari RDC” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fdigital-activism-2018%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”97990″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/digital-activism-2018/”][vc_column_text]The 2018 Digital Activism Award is sponsored by Private Internet Access[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fjournalism-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Wendy Funes” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fjournalism-2018%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”98000″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/journalism-2018/”][vc_column_text]The 2018 Journalism Award is sponsored by Vice News[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”2017 Fellows” tab_id=”1524472475785-d2464a89-c53e”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”2017 Fellows” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Selected from over 400 public nominations and a shortlist of 16, the 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows exemplify courage in the face of censorship. Learn more about the fellowship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Rebel Pepper” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Farts-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”94724″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/04/arts-fellow-2017/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fcampaigning-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Ildar Dadin” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fcampaigning-fellow-2017%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”94725″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/04/campaigning-fellow-2017/”][vc_column_text]The 2017 Campaigning Award is supported by Doughty Street Chambers[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fdigital-activism-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Turkey Blocks” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fdigital-activism-2017%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”94726″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/04/digital-activism-2017/”][vc_column_text]The 2017 Digital Activism Award is sponsored by Private Internet Access[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fjournalism-2017%2F|||”][vc_custom_heading text=”Maldives Independent” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F04%2Fjournalism-2017%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”94727″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/04/journalism-2017/”][vc_column_text]The 2017 Journalism Award is sponsored by CNN[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”2016 Fellows” tab_id=”1501487515382-d17ff4cd-299e”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”2016 Fellows” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts | Murad Subay” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F11%2Farts-fellow-2016%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”74790″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/arts-fellow-2016/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning | Bolo Bhi” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F03%2Fcampaigning-2016%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”82685″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/03/campaigning-2016/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism | GreatFire” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F03%2Fdigital-activism-2016%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”82689″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/03/digital-activism-2016/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism | Zaina Erhaim” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F03%2Fjournalism-2016%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”82702″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/03/journalism-2016/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Music in Exile | Smockey” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F03%2Fmusic-in-exile-2016%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81098″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/03/music-in-exile-2016/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][vc_tta_section title=”2015 Fellows” tab_id=”1501487515639-5231aa25-0705″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”2015 Fellows” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts | El Haqed” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2015%2F03%2Farts-2015%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81111″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/03/arts-2015/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning | Amran Abdundi” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2015%2F03%2Fcampaigning-2015%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81118″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/03/campaigning-2015/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism | Tamás Bodoky” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2015%2F03%2Fdigital-activism-2015%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81126″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/03/digital-activism-2015/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism | Rafael Marques de Morais” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2015%2F03%2Fjournalism-2015%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81131″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/03/journalism-2015/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism | Safa Al Ahmad” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2015%2F03%2Fjournalism-2015-2%2F|||”][vc_single_image image=”81138″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2015/03/journalism-2015-2/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_tabs][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Fellows News” category_id=”16143″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes”][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”5px”][vc_custom_heading text=”2020 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship Timeline” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”awards-timeline-grid”][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80944″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Coming Soon

NOMINATIONS[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80945″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]DEC 2019

JUDGING PANEL[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80946″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]JAN 2020

SHORTLIST ANNOUNCED[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80947″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Spring 2020

AWARDS FELLOWSHIP WEEK[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80948″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Spring 2020

AWARDS GALA[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”80949″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]APR 2020 – MAR 2021

AWARDS FELLOWSHIP[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”About the Awards Fellowship” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”awards-timeline-grid”][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”94804″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]One Full Year

Fellows receive 12 months of direct assistance, starting with an all-expenses-paid training week in London in April 2018.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Survive

Index helps fellows build key partnerships, troubleshoot and receive expert support in multiple areas including digital security, strategy and communications.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Thrive

Fellows work with Index and partners to identify and realise key strategic goals.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Amplify

Index promotes news and regional developments through our magazine, website and social media.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Network

Fellows become part of a supportive community of free expression champions worldwide.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”What we look for in selecting Awards Fellows” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”awards-timeline-grid”][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_single_image image=”94805″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Timeliness

A significant contribution within the past 12 months.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Resilience

Courage to speak out, persisting in the face of adversity.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Innovation

Creative ways of promoting free expression or circumventing censorship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Impact

Evidence of shifting perceptions, influencing public or government opinion, contributing to legislative change.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/6″][vc_column_text]Need

Those cases where the 2018 Awards Fellowship can potentially add the most value.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”We award Fellowships in four categories” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1501508115518{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Arts” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for artists and arts producers whose work challenges repression and injustice and celebrates artistic free expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1501508268476{background-color: #d98c00 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Campaigning” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for activists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in fighting censorship and promoting freedom of expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1501508309950{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital Activism” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for innovative uses of technology to circumvent censorship and enable free and independent exchange of information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1501508333043{background-color: #d98c00 !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalism” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]for courageous, high-impact and determined journalism that exposes censorship and threats to free expression[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”15px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes”][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Awards.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1528707303361{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/EMK_2426web-1460×490-1.jpg?id=99905) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_empty_space height=”30px”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” css=”.vc_custom_1500453384143{margin-top: 20px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”SPONSORS” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1484567001197{margin-bottom: 30px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The Freedom of Expression Awards and Fellowship have massive impact. You can help by sponsoring or supporting a fellowship.

Index is grateful to those who are supporting the 2019 Awards Fellowships:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80918″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://uk.sagepub.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80921″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://www.google.co.uk/about/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”85983″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.privateinternetaccess.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”85977″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.edwardian.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105358″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mainframe.com/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105536″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”http://www.vodafone.com/content/index.html#”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105360″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.francemediasmonde.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105359″ img_size=”234×234″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/index.html”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”80924″ img_size=”200×200″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”https://psiphon.ca/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105361″ img_size=”200×200″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.telegraph.co.uk/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105363″ img_size=”200×200″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.societyofeditors.org/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” el_class=”container container980″][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”105365″ img_size=”200×200″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.news.co.uk/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][vc_single_image image=”106100″ img_size=”200×200″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.mirror.co.uk/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″ offset=”vc_col-xs-6″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

If you are interested in sponsorship you can contact [email protected]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]