21 Aug 2015 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features, Youth Board

This is the ninth of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Lejla Becar is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

In 2005, the chair of Visoko municipality cancelled a concert due to be performed by Skroz, a rock band from Bosnia and Herzegovina. He justified his decision by saying that the concert and the sponsor (a famous beer brand) would be insulting for Muslims and Muslim youth.

These decisions riled up both the organisers of the events and also citizens, both Muslim and non-Muslim. One of the main organisers was Adnan Jašo Jašarspahić, editor of independent radio station Radio Q. He was to face consequences in the years to come due to his decision not to obey the chair and ignore the cancellation of the Skroz concert. It was held 15 days after cancellation.

This was not an isolated event. In 2006 Croatian band Let 3 were not allowed to perform in Travnik, a small municipality in central Bosnia. In 2008, Bosnian group Dubioza Kolektiv were banned from performing in Goražde. In the meantime, the Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA) penalised Bosnian radio station Radio 202 — fining them more than €5,000 — for playing hip-hop music on air. The agency stated it had been offensive.

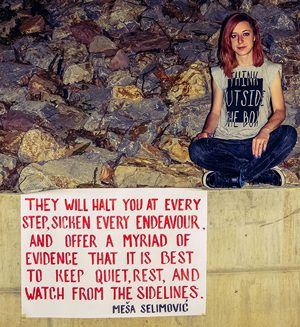

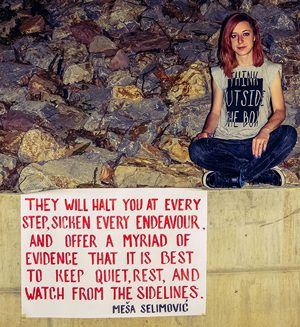

The situation now? In my town, cultural events for youth are a phenomena. More and more young people are leaving, turning to radical Islam or simply living within an oppressive system without complaint. The people fighting the system were silenced. Ten years of violating the right to freedom of expression took its toll and now the government has succeeded in creating a society that is obedient, ignorant and passive.

Lejla Becar, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Related:

• Anastasia Vladimirova: A ruthless crackdown on independent media

• Simeon Gready: An over-the-top regulation policy

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Muira McCammon: GiTMO’s linguistic isolation

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

20 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, Russia, Youth Board

This is the eighth of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Anastasia Vladimirova is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

On July 29, Russia’s independent media support fund, Sreda, announced it would be liquidated due to lack of funding.

Russia’s Ministry of Justice declared the fund a “foreign agent” after its mandatory check into the organisation’s finances.

Direct interference by the Russian government became possible in 2012 after President Vladimir Putin approved a law requiring all non-governmental organisations that receive foreign funding and engage in vaguely defined political activity to register as foreign agents with the Russian Ministry of Justice.

Since its inception, however, Sreda had received money from Dmitry Zimin, a Russian entrepreneur and investor in science and education, whose nonprofit foundation Dynasty closed earlier this year due to the scrutiny imposed by the Ministry of Justice under the same law. Given the absence of foreign funding, the liquidation of Sreda is an example of Russia’s ruthless crackdown on independent media masquerading as a legal fight against the alleged foreign influence on Russia’s political and civic life.

Colta, Novaya Gazeta and TV Rain Channel are just a few examples of Sreda’s now former grantees that struggle to keep up their independent voices in the media landscape dominated by state-sponsored outlets.

Anastasia Vladimirova, Russia

Related:

• Simeon Gready: An over-the-top regulation policy

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Muira McCammon: GiTMO’s linguistic isolation

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

20 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, South Africa, Youth Board

This is the seventh of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Simeon Gready is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

Earlier this year, South Africa’s Film and Publication Board (FPB) released their Draft Online Regulation Policy.

The proposed regulations of this policy have huge implications for freedom of expression in South Africa, which can be summarised into the following:

• The policy claims to apply to films, games and “certain publications”. This is vague language that allows it to cover anyone publishing anything on the Internet.

• The policy allows for regulation of private personal communications.

• The policy states that anyone wishing to publish content on the internet need to apply and pay for an agreement with the FPB, meaning that individuals would be required to pay for their fundamental human right to freedom of expression.

• The policy further violates freedom of expression in that it asserts that it retains the right to take down “violent” content published by media outlets, thereby disallowing the media from being able to carry out its social responsibilities.

• The policy allows “classifiers” from the FPB to search distributor’s premises, unhindered and with no responsibility for loss or damage.

Worryingly, it has recently been announced that this policy has been approved to inform a new film and publications amendment bill. If signed into law, the repressive tactics outlined above could become a reality for South African citizens.

Simeon Gready, South Africa

Related:

• Anastasia Vladimirova: A ruthless crackdown on independent media

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Muira McCammon: GiTMO’s linguistic isolation

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

19 Aug 2015 | mobile, News and features, United States, Youth Board

This is the fifth of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Muira McCammon is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

Guantanamo Bay (GiTMO) is a place where language barriers embody part of the institution’s social architecture.

Two years ago, Peter Jan Honigsberg of the University of San Francisco wrote about linguistic isolation, using the experiences of an Uzbek detainee to highlight this reality. But, we know that during various points throughout GiTMO’s history, dictionaries have been used and even written by detainees. In March 2004, the U.S. Joint Task Force Guantanamo published a revision of its 2003 Camp Delta Standard Operating Procedure, adding “dictionaries” to the list of materials banned from the Guantanamo Bay detainee library. There was no immediate reason given for this policy change, even though, according to a report later released by the US Department of Defense, detainees speak over 18 native languages.

Furthermore, Mahvish Khan, an interpreter and Pashtun-American lawyer, published My Guantanamo Diary: The Detainees and the Stories They Told Me. In the book, Khan shared this anecdote about Taj Mohammad, a then twentysomething from Kunar, Afghanistan:

“He asked us repeatedly to bring him a Pashto-English dictionary so that he could improve his English. Over several months, he had compiled and memorised a list of almost one thousand English words. But during a routine search, the guards had found and confiscated his neatly written glossary.”

Speech is a fickle concept in detention centres, and the story of Mohammad’s confiscated, self-written lexicographic resource raises questions about how detainees in GiTMO or any detention centre for that matter can effectively combat linguistic isolation.

Muira McCammon, USA

Related:

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities