22 Jul 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”108086″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

European Commission

Rue de la Loi 200

1049 Brussels

Belgium

19 July 2019

Dear President von der Leyen,

We are writing as members of the press freedom community to congratulate you on your appointment as President of the European Commission, and to urge you to ensure that media freedom, the protection of journalists, and EU citizens’ access to information are top political priorities over the coming term of your Commission.

The last Commission took important steps to address media freedom. But given the rapidly changing media environment, increasingly severe threats and restrictions to press freedom, and the recent murders of journalists, more must be done. We, the undersigned organizations, strongly urge you to appoint a Vice-President of the new Commission with a clear and robust mandate to use all available EU mechanisms, including policy, legislation, and budget, to defend press freedom and the safety of journalists. In particular, we urge you to explicitly list this mandate in your mission letter to one of the Vice-Presidents establishing it as a political priority over the next five-year term.

We ask that the Vice-President have a sufficiently robust and far-ranging mandate to address the following areas of reform:

- Creating an enabling legal and regulatory environment for free, independent, pluralistic, and diverse media and the safety of journalists, whether staff, freelancers, or bloggers. Journalists need to be protected from judicial harassment, arbitrary surveillance, defamation, overly broad national security and anti-terrorist legislation, as well as SLAPP and tax laws.

- Protecting journalists, freelancers, and bloggers from physical, legal, psychological, and digital threats, and ensuring access to effective protection and prevention measures and mechanisms, with specific attention to the risks facing female journalists.

- Combating impunity for all attacks against journalists, freelancers, and bloggers, including support and capacity-building for law enforcement, prosecutors, and the judiciary and the development of specialized protocols for investigations.

- Continuing to combat disinformation through robust public defense of independent journalism and its critical importance in democracy. This should accompany efforts to increase public understanding of media freedoms, supporting social media self-regulation, and building media literacy.

- Supporting sustainable models for independent journalism in promoting media independence, pluralism, and diversity, as well as allowing for effective self-regulation, capacity building, and training.

Media freedom and pluralism are pillars of modern democracy. For the next Commission to guarantee European citizens their right to access to information, it must use the coming term to address the numerous threats to journalism. We hope you will take steps to ensure it does.

We would welcome the opportunity to meet with you and thank you in advance for taking our concerns into consideration. We look forward to receiving your response.

Sincerely,

Alliance Internationale de Journalistes

Article 19

Association of European Journalists

Committee to Protect Journalists

English PEN

European Federation of Journalists

European Journalism Centre

European Media Initiative

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

Free Press Unlimited

Global Forum for Media Development

IFEX

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute

Media Diversity Institute

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

Rory Peck Trust

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 2019 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Scholar at Risk

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106191″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“We in Syria were living in a big prison, without freedom, without good education, without good quality of life, without any desire of development,” says Dr. Kassem Alsayed Mahmoud, a food science and agricultural engineering researcher. “We have in Syria only five universities while we have more than 200 prisons.”

In 2009, Alsayed Mahmoud returned home to Syria after getting his masters and doctorate degree in France. He began working at Al-Furat University, where he quickly encountered the multitude of issues that academics in Syria face. In his experience as a professor and researcher in Syria, there is a serious lack of resources, experience and research freedom, in addition to issues of bureaucracy and corruption that all combine to create an environment that discourages and prevents academic freedom.

Despite his position as a professor at Al-Furat University and his age at the time, 37, he was forced into the one year of military service that is compulsory for Syrian citizens. He entered the military at the end of 2010 but was kept past his one-year mandatory service for an undetermined amount of time. By the end of 2012, Alsayed Mahmoud decided to defect from the military and leave Syria.

From there, Alsayed Mahmoud made his way to Turkey with the help of rebels, and then Qatar, where he remained for a year, before Scholars at Risk helped him obtain a research position in a lab at the Ghent University in Belgium. This position served as a starting point from which Alsayed Mahmoud then moved to a research position at the Universite Libre de Bruxelles, where he worked on the valorisation of bioorganic wastes from the food industry, to see if food waste could be converted into something more useful like energy, other chemicals or materials that could be helpful in manufacturing processes.

In August 2018 Alsayed Mahmoud moved back to France because of his French refugee status, where he is still searching for a job in his field.

Although he describes the higher education system in Syria as a “tragedy” and “disaster”, he still hopes to return to Syria and pursue academic research in order to help rebuild the country.

“For me, I hope very soon to be a free human living in the free Syria,” says Alsayed Mahmoud. “I hope that one day I, and all, Syrian academics could come back home and do our research with freedom as all our colleagues in Europe and developed countries do.”

Dr. Alsayed Mahmoud spoke to Emily Seymour, an undergraduate student of journalism at American University, for Index on Censorship.

Index: What are your hopes for Syria and yourself?

Alsayed Mahmoud: To stop the war in Syria as soon as possible. We need to change the dictatorial regime and clean the country of all occupation and terrorist forces. I want to go back to Syria to continue my work at a university and participate in building our country. I hope that Syria can establish the principles of freedom; and change the constitution to guarantee that no dictator could stay in power for a long time. For me, I hope very soon to be a free human living in the free Syria.

Index: How have you changed in since leaving Syria?

Alsayed Mahmoud: Since leaving Syria seven years ago, I feel that I have been living with an artificial heart. Despite having found a safe place, the help of people and governments in Europe, I still need to breathe the air of Syria, to meet my friends and loved ones, and be proud to develop the country. Seven years is long enough to know that some people who should represent humanity are the cause of disasters because they do not care about other people or about the next generations. These are the people in power who are destroying the earth by making decisions out of only self-interest, waging wars, polluting the earth and increasing hate speech and racism.

Index: Did going to France for your education impact how you viewed Syria when you returned? If so, in what way?

Alsayed Mahmoud: We in Syria were living in a big prison, without freedom, educational opportunities or a good quality of life. There was no desire to develop the country, which has been under a dictatorial regime and one-party rule since 1970. In Syria, we have only five universities but we have more than 200 prisons. When I returned to Syria, I tried to apply what I learned in France, but unfortunately, they forced me to do the mandatory military service in December 2010, despite my professorial position at a university and my age (37 years).

Index: How did the revolution impact higher education in Syria?

Alsayed Mahmoud: Before the revolution, higher education was not in a good situation. There was a lack of materials, a lack of good academics and staff due to the fact that most got their PhDs from Russia and came back without any experience. Very few research papers from Syria were published in the international reviews. There was no academic freedom because many projects were refused by the secret service because they thought the research would interfere with the security of the country. Most university students and staff, especially males, were killed, arrested, tortured, left the country or were forced into the war. You had no choice if you stayed: kill or be killed. Three of five Syrian universities are out of service or displaced to another city. There is also a lack of academics, staff, materials and even students. There is no higher education system in Syria now. It’s a tragedy and disaster.

The revolution also started at universities, because students and researchers believed that the future of the country was in danger. We knew that the situation of higher education in Syria is the worst it’s been since 1970, but we believed that the development of any country is based on research and higher education. The situation now is the result of about 50 years of dictatorship, and the revolution was the right step to start a new life in Syria. We need only some time without any terrorism or occupation to create a free and well educated new generation to build what the terrorist occupations destroyed.

Index: What was it about your experience in the army that prompted you to defect and leave the country?

Alsayed Mahmoud: Before I was forced to do the mandatory service, I was completely against the dictatorial regime and I hoped that one day I could feel free to say and do what I want in Syria.

I suffered a lot when I was in the army, we were forced to obey the stupid orders of the officers who could humiliate you if they knew that you have already finished your PhD in Europe or in a developed country and came back to Syria. As the revolution started in March 2011, they prevented us from seeing what was going on outside the military camps, they did not give us our freedom even when we finished our one-year service and kept us for an indefinite amount of time. From the first day of the revolution, I had decided to defect, but out of fear for my family, I stayed until they were safe. I defected because I am against this dictatorial regime and the army that killed civilians and innocent children, and destroyed the country only because Syrians wanted to be free.

Index: What does your current research focus on?

Alsayed Mahmoud: I returned to France in August 2018 after three years in Belgium because I have French refugee status, but I am still looking for a job in my field. My previous research focused on the valorisation of bioorganic wastes from the food industry. The goal was to give more value to food waste by producing high valued products like lactic acid, which is often used in different domains like food and pharmacy. We developed a fermentation mechanism for lactic acid production in order to valorise potato effluents, which are generated from potato processes.

Index: How has the support of organisations like Scholars at Risk (SAR) been important in your journey as an academic?

Alsayed Mahmoud: Scholars at Risk has had a very important impact on my career. Since I left Syria, I looked for help to find a safe place to continue my work as a researcher. SAR was the most helpful organisation in my case because they could help me to find a host lab — the Laboratory of Food Technology and Engineering — with a grant at Ghent University in Belgium. This was the first step to then find another two year grant at the 3BIO lab in the Universite Libre de Bruxelles in Brussels, where I worked on the valorisation of bioorganic wastes from the food industry. SAR has always been supportive, even after I finished my first year at Ghent University.

Index: Why do you believe academic freedom is important?

Alsayed Mahmoud: Academic freedom is one of the most important pillars for the development of any country. Academics are often leaders that nurture the success of a country. If they are not free to think, criticise and research, they will not be able to help foster development.

Index: In your experience, what has been the difference between the three different academic settings that you’ve been in, in Syria, France and now Belgium?

Alsayed Mahmoud: I could not find a big difference between France and Belgium, but I believe that the academic situation in Syria is very far from being as good as in Europe. In my experience, academic freedom in Syria is one of the worst in the world. Academic freedom is a more important ideal in France and Belgium. The influence of power on the research in Europe is mostly positive and academia and governments often work together to develop the country. In Syria power is really against research and development despite paying lip service to it in the media. The freedom of research is the key to development here in Europe, while in Syria research is controlled by the regime and Assad’s secret services. Generally, there is a very big budget for research here in Europe, while in Syria we have just a drop of that budget, which is also often stolen before reaching us or used for bad purposes. The staff in Syria was mostly educated in Russia and other countries that have low education levels.

The number of universities is a sign of a healthy education system in France and Belgium, while in Syria we have only five universities but more than 200 prisons. You can generally get what you need to carry out your research in Europe without any big financial or political problems, but in Syria, researchers are very limited by materials and budgets. The freedom of mobility to any country for the purposes of attending a scientific event is not a big issue here in Europe, while as a Syrian researcher you are limited by visa and political problems. I hope that one day I, and all Syrian academics, can return home and do our research in freedom — as all our colleagues in Europe and developed countries do — and be proud to be a Syrian researcher.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105189″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/”][vc_column_text]This article was created in partnership with Scholars at Risk, an international network of institutions and individuals whose mission it is to protect scholars, promote academic freedom, and defend everyone’s right to think, question, and share ideas freely and safely. By arranging temporary academic positions at member universities and colleges, Scholars at Risk offers safety to scholars facing grave threats, so scholars’ ideas are not lost and they can keep working until conditions improve and they are able to return to their home countries. Scholars at Risk also provides advisory services for scholars and hosts, campaigns for scholars who are imprisoned or silenced in their home countries, monitoring of attacks on higher education communities worldwide, and leadership in deploying new tools and strategies for promoting academic freedom and improving respect for university values everywhere.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1554827510836-1e64b768-ccba-7″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

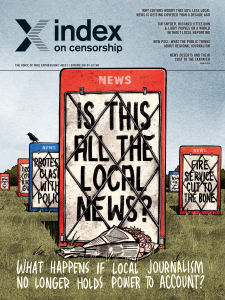

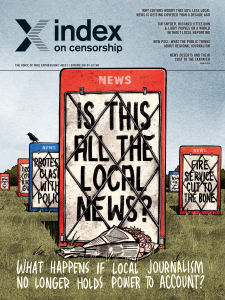

27 Mar 2019 | Magazine, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Worrying about a local newspaper closing or reporters being centralised is not just nostalgia, it’s being concerned that our democratic watchdogs are going missing, says Rachael Jolley in the spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Is this all the local news? The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Regional daily newspaper the Eastern Daily Press is closing two of its district offices, in Cromer on the north Norfolk coast, and in Diss, a Norfolk market town.

This matters to me because the EDP was the first place I worked as a journalist and it was then one of the UK’s biggest local papers, with at least 10 offices, all employing reporters. Some of the offices had one or two reporters, some had 10, and the Norwich head office had about 50 editorial staff. When I joined as a trainee reporter, the big bosses mandated that we worked in at least three different offices within two years. We went out and about on an almost daily basis, talking to people and covering events. These days, national newspaper editors dream of having as many reporters as the EDP had in the 1990s.

So why does this matter? And should anyone care when the small newspaper office in Cromer closes? After all, as the management of the EDP said, everyone is online now, so we can do business digitally. And, yes, most of us can communicate by email and we could email our news tips to a far-flung newsdesk.

We could, but perhaps we won’t bother.

And, yes, you can do business digitally: we can send money and adverts around the world at the click of a mouse. But the stuff at the guts of a local newspaper, the finding out what is going on and hearing a sniff of a story in the pub, will that still go on or will reporters be left to depend on social media as a source?

If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? Will they even know who to call, or who to email?

When a massive fire starts down by the King’s Lynn docks, will anyone from the local newspaper be there to see it (as I was one midnight when I saw the flames out of my bedroom window)?

The answer is clearly that they will not. News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.

Local newspapers (and, to some extent, local radio stations) were, and in some places still are, fighting for the little guy against the monolith for the old person, say, who is inundated by noisy construction work morning, noon and night. They bring to the attention of the public a council plan to close a massively popular library, or a bid to cement over a local swimming pool and turn it into flats. They cover a big crown court case about a million-pound corruption that ends with shops closing and jobs being lost.

When things went wrong, the local media were there to make sure people knew about it, and what the problems were. They could knock on the door of the powerful and shout for something to change.

And, yes, these things don’t have to be done only in print – a website can still cover stories and reach an audience – but if there are no reporters on the ground, and they are increasingly based far away from the stories they cover, they will increasingly miss knowing about scandals, corruption and the death of the totally brilliant grandmother who was the heart of the place.

One ex-newspaperman told me he recently walked into a city office to find all the staff for local newspapers from one part of Scotland sitting there, together. They had all become long-distance reporters, at arm’s length from the places they reported on.

This is more than an industrial tipping point. This is a gradual unpicking of part of democracy: scandals that need to be held up to the light will get missed; local authorities that spend public money will have no one watching to see if they are doing it according to the rules.

There is also cause to worry about the coverage of the courts and the justice system. As the former lord chief justice of England and Wales, Lord Judge, told Index: “Open justice is one of the essential safeguards of the rule of law. The presence of the media in our courts represents the public’s entitlement to witness the administration of justice and assess whether, and how, justice is being done. As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high-profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded, eventually to virtual extinction.”

Lord Judge is right. It is likely that budget-stretched local newspaper managers will drop the coverage that costs them the most money. The difficult stuff will get ignored and replaced with fun videos of cats and other animals. The person who sifts steadily through a council agenda, page by page, will disappear, to be replaced by a “content manager” whose job is to produce crowd-pleasing clickbait fare.

Mike Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post in the UK, said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were. There are large numbers of councils right across the country making big decisions, involving millions of pounds of public money, who may never see a local reporter. Many local authorities will be operating in the knowledge that no one will ever ask them an awkward question. Which, obviously enough, does nothing to help build trust in local democracy.”

The problem, some argue, is that the public are not really bothered about losing these skills or services. If they were, they would be willing to support them. Local news has to be paid for, and the companies that have been producing it have to make money to survive. If the public don’t care enough to pay for it, they will move on to doing other things. That’s the way the market works.

People are willing to pay for a cinema ticket, or to go to the football, or for a Netflix subscription, but right now it appears that not many are willing to pay for local news. And if no one funds it, it disappears. Will it be a case of appreciating local news reporting only when it is gone?

There’s even more to worry about when it comes to news vacuums appearing. As people feel more and more disconnected from the place where they live, they move into a state of solitude, not knowing what is going on around them. That breeds discontent, a feeling of being ignored, and when a community doesn’t exist there’s no one to lean on when things go wrong.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

There is a public right to information about what locally elected officials are doing, but there is no public right to a newspaper.

If no one wants to buy it, and if no one cares about it, it is likely to disappear. But there is a lot more to lose than a place when you find detailed coverage of your local football team (much appreciated though that is by many). There are deep societal costs.

There are some signs of public discontent which may be linked to declining local news coverage, and might be a sign that people are waking up to what is going missing when local media operations close down or pull away from certain types of coverage.

For this issue, we commissioned YouGov to carry out a poll of the public and we found that 40% of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed down.

Also, Libby Purves, a columnist at The Times who started her career on a local radio station, tells us she believes part of the discontent that produced Brexit was about people in far-flung places and regional cities feeling their news and views were being ignored. She also talks to us about her earlier years working on Radio Oxford and the close relationship the station had with people who worked in and around the city. They would march into the centrally located studio and tell reporters when they were getting it wrong, she says.

The question is: how can that be replaced today? Can it be done on social media, for instance? Or is it a bit like barking at a tree? You have made noise, but the tree definitely isn’t listening?

For those of you who thought that threats to local news were just in your own country, think again. We looked into this issue around the globe and found some of the same problems developing in China, Argentina, the USA and Belgium, among others. We interviewed people in Italy, Germany, India, the UK and Nigeria. The worries are often the same, the reasons slightly different.

Many of those who fight for freedom of expression feel that declining numbers of local reporters just make it easier for governments to cover up scandals, leave the public ill-informed, and make sure only the information they want is out there.

There are some bright sparks who have ideas about how the important services that local news has provided could work differently in the future. There are people starting their own local paper, focusing on digging out stories, growing circulation and making enough money to keep going.

Other ideas are also emerging. The BBC’s local democracy reporters project, discussed in this magazine, is one way of funding specialists who have time to dig through council agendas to find out what is going on. What about finding specialist bloggers with in-depth knowledge on their particular local magistrates’ court, for instance, and having a Gofundme campaign to get up to 3,000 locals to pay £5 or £10 a month for a twice-weekly email of fabulously detailed and incisive analysis of what is happening?

Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on local news

Index on Censorship’s spring 2019 issue is entitled Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the local news?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F03%2Fmagazine-is-this-all-the-local-news%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

With: Libby Purves, Julie Posetti and Mark Frary[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/03/magazine-is-this-all-the-local-news/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Artists in Exile, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104099″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]“If you want to make films in Burundi, you either self-censor and you remain in the country or if you don’t, you have to flee the country,” Eddy Munyaneza, a Burundian documentary filmmaker, told Index on Censorship.

Munyaneza became fascinated in the process of filmmaking at a young age, despite the lack of cinematic resources in Burundi.

He now is the man behind the camera and has released three documentaries since 2010, two of which have drawn the ire of the Burundian government and forced Munyaneza into exile.

His first documentary — Histoire d’une haine manquée — was released in 2010 and has received awards from international and African festivals. The film is based on his personal experience of the Burundian genocide of 1993, which took place after the assassination of the country’s first democratically elected Hutu president Ndadye Melchoir. It focuses on the compassionate actions he witnessed when his Hutu neighbours saved him and his Tutsi sisters from the mass killings that swept the country. The film launched Munyaneza’s career as a filmmaker.

Munyaneza was honoured by Burundi’s president Pierre Nkurunziza for his first film and his work was praised by government officials. But the accolades faded when he turned his camera toward Nkurunziza for his second film in 2016.

The film, Le Troisieme Vide, focused on the two-year political crisis and president’s mandate that followed Nkurunziza’s campaign for an unconstitutional third term in April 2015. During the following two years, between 500 and 2,000 people were tortured and killed, and 400,000 were exiled.

The filming of his second documentary was disrupted when Munyaneza started receiving death threats from the government’s secret service. He was forced to seek asylum in Belgium in 2016 for fear of his life. Through perseverance and passion, he quietly returned to Burundi in July 2016 and April 2017 to finish his short film.

Exile hasn’t affected Munyaneza’s work: in 2018 he released his third film, Lendemains incertains. It tells the stories of Burundians who have stayed or left the country during the 2015 political tension. He secretely returned to Burundi to capture additional footage for his new film, which premiered in Brussels at the Palace Cinema and several festivals.

“I lead a double life, my helplessness away from my loved ones, and the success of the film on the other,” he said. He continues to work in exile, but also works toward returning to Burundi to see his wife and kids who currently reside in a refugee camp in Rwanda, and to create film, photography and audio programs for aspiring Burundian filmmakers.

Gillian Trudeau from Index on Censorship spoke with Munyaneza about his award-winning documentaries and time in exile.

Index: In a country that doesn’t have an abundance of film or cinema resources, how did you become so passionate about filmmaking?

Munyaneza: I was born in a little village where there was no access to electricity or television. At the age of 7, I could go into town for Sunday worship. After the first service, I would go to the cinema in the centre of the town of Gitega. We watched American movies about the Vietnam war and karate films, as well as other action movies which are attractive to young people. After the film my friends and I would have debates about the reality and whether they had been filmed by satellites. I was always against that idea and told them that behind everything there was someone who was making the film, and I was curious to know how they did it. That’s why since that time I’ve been interested in the cinema. Unfortunately, in Burundi, there is no film school. After I finished school in 2002, I began to learn by doing. I was given the opportunity to work with a company called MENYA MEDIA which was getting into audiovisual production and I got training in lots of different things, cinema, writing, and I began to make promotional films. The more I worked, the more I learned.

Index: How would you characterise artistic freedom in Burundi today, and is that any different to when you were growing up?

Munyaneza: To be honest, Burundian cinema really got going with the arrival of digital in the 2000s. Before 2000 there was a feature film called Gito L’Ingrat which was shot in 1992 and directed by Lionce Ngabo and produced by Jacques Sando. After that, there were some productions by National Television and other documentary projects for TV made in-house by National Television. I won’t say that the artistic freedom in those days was so different from today. The evidence is that since those years, I can say after independence, there have not been Burundian filmmakers who have made films about Burundi (either fictional or factual). There were not really any Burundian films made by independent filmmakers between 1960 and 1990. The man who dared to make a film about the 1993 crisis, Kiza by Joseph Bitamba, was forced to go into exile, just as I have been forced to go into exile for my film about the events of 2015. So if you want to make films in Burundi, you either self-censor and you remain in the country or if you don’t, you have to flee the country.

Index: You began receiving threats after you made your second film, Le troisieme vide, in 2016. The film focused on the political crisis that followed the re-election of president Nkurunziza. Why do you think the film received such a reaction?

Munyaneza: Troisieme Vide is a short film which was my final project at the end of my masters in cinema at Saint Louis in Senegal. I knew that just making a film about the 2015 crisis would spark debate. Talking about the events which led to the 2015 crisis, caused by a president who ran for a third term, which he is not allowed to do by the constitution, I was sure that when this film came out I would have problems with the government. But I am not going to be silent like people who are older than me have done, who did not document what went on in Burundi from the 1960s, and have in effect just made the lie bigger. I want to escape this Burundian fate, to at least leave something for the generations to come.

Index: How did you come to the decision to leave Burundi and what did that feel like?

Munyaneza: Burundi is a beautiful country with a beautiful climate. My whole history is there – my family, my friends. It is too difficult to leave your history behind. The road into exile is something you are obliged to do. It’s not a decision, it’s a question of life or death.

Index: How is life in Belgium, being away from your wife and children?

Munyaneza: It is very difficult for me to continue to live far from my family ties. I miss my children. I remain in this state of powerlessness, unable to do anything for them, to educate them or speak to them. It is difficult to sleep without knowing under what roof they are sleeping.

Index: How has your time in exile affected your work?

Munyaneza: On the work front, there is the film which is making its way. It has been chosen for lots of festivals and awards. I have just got the prize (trophy) for best documentary at the African Movie Academy Award 2018. I was invited but I couldn’t go. I lead a double life, my helplessness away from my loved ones, and the success of the film on the other. I have been invited to several festivals to present my film, but I don’t have the right to leave the country because of my refugee status. I am under international protection here in Belgium.

Index: You have returned to your home country on several occasions to film footage for your films. What dangers are your putting yourself in by doing this? And what drives you to take these risks?

Munyaneza: I risked going back to Burundi in July 2016 and in April 2017 to finish my film. To be honest, I didn’t know how the film was going to end up and sometimes I believed that by negotiating with the politicians it could take end up differently. When you are outside (the country) you get lots of information both from pro-government people and from the opposition. The artist that I am I wanted to go and see for myself and film the situation as it was. Perhaps it was a little crazy on my part but I felt an obligation to do it.

Index: Your most recent film, Uncertain Endings, looks at the violence the country has faced since 2015. In it, you show the repression of peaceful protesters. Why are demonstrators treated in such a way and what does this say about the future of the country?

Munyaneza: The selection of Pierre Nkurunziza as the candidate for the Cndd-FDD after the party conference on 25 April provoked a wave of demonstrations in the country. The opposition and numerous civil society bodies judged that a third term for President Nkurinziza would be unconstitutional and against the Arusha accords which paved the way for the end of the long Burundian civil war (1993-2006). These young people are fighting to make sure these accords, which got the country out of a crisis and have stood for years, are followed. Unfortunately, because of this repression, we are back to where we started. In fact, we are returning to the cyclical crises which has been going on in Burundi since the 1960s. But what I learnt from the young people was that the Burundian problem was not based on ethnic divides as we were always told. There were both Hutu and Tutsi there, both taking part in defending the constitution and the Arusha accords. It is the politicians who are manipulating us.

Index: Do you hold out any hope of improvements in Burundi? Do you hope one day to be able to return to your home country?

Munyaneza: After the rain, the sun will reappear. Today it’s a little difficult, but I am sure that politicians will find a way of getting out of this crisis so that we can build this little country. I am sure that one day I’ll go back and make films about my society. I don’t just have to tell stories about the crisis. Burundi is so rich culturally, there are a lot of stories to tell in pictures.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mnGPlAd1to8&t=24s”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1543844506394-837bd669-b5fd-5″ taxonomies=”29951, 15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]