19 Dec 2018 | Americas, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, Honduras, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winner and 2018 Journalism Fellow Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes at the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards (Photo: Elina Kansikas)

“Violence is a way of keeping society under control because a lot of what people do or don’t do is a reaction to fear,” Wendy Funes, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Journalism, tells Index on Censorship. “It becomes an indirect method of control, not just over society, but journalism as well.”

Funes worries this kind of violence has become “normalised” in Honduras and says the shooting and wounding of journalist Geovanny Sierra — who has survived numerous attempts on his life — by military police while covering protests of electoral fraud in late November is just the latest example. The Honduran authorities issued a statement saying that law enforcement was attacked first, which is why they started shooting. “With this they have justified the crime,” Funes says, adding that nothing is being done about the attacks on journalists in the country: “The most terrible thing is the impunity that exists because if something like this happened in another country it would a scandal, but here it is already forgotten.”

Funes is no stranger to covering either corruption or protest and has had her own brushes with heavy-handed state forces, although she says for the most part she has been lucky. “I’ve had training opportunities in self-protection and security,” she says. “I am also very cautious — I try to plan my routes and if I go inter dangerous areas, I try to have a safety protocol, to have alliances with civil society groups, so if something happens to me I can let them know.”

Recently, Funes’ investigative website Reporteros de Investigacion has been focusing on issues such as human trafficking, violence against student protesters, femicide and the high-level cocaine trafficking case involving Juan Antonio Hernández, brother of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández. The website has also been covering the caravan of people fleeing persecution, poverty and violence in the country. “They are facing a very cruel situation,” Funes says.

Honduran migrant Daniel Portillo

Although Reporteros de Investigacion doesn’t have the resources to cross the border, it has been working closely with some of those who have fled, such as 25-year-old Daniel Portillo, who left Honduras in search of the “American dream”. Portillo is now in Mexico. “He has found someone who works with migrants and helps migrants,” Funes, who first met him when she was covering protests in San Pedro Sula, a city in the northwest of Honduras, said. “He is a young person with a lot of leadership qualities, a lot of desire to advocate for other young people.”

While in Honduras Portillo organised sports tournaments in an area controlled by the criminal gang MS-13. “He resisted joining the gang,” Funes says. “He was always trying to negotiate with them so that he could help other young people so they wouldn’t get into drugs or alcohol.”

Writing in Reporteros de Investigacion, Portillo explains the difficulty of explaining to his young daughter that he left so she could have a better future: “If God allows it, we will see each other again or else, I am writing this letter to you in case unfortunately they killed me on the way and buried me; my heart is that of a warrior and I will continue forward, whatever happens, my mother suffers for my departure.”

“He told me that he has seen many people carved up since he was a child,” Funes tells Index. “Violence weighed on his psyche and made him very vulnerable young person. He told me that he looked for employment in Honduras, and when he could not find he decided to migrate with the caravan.”

It is such vulnerability that makes poor Hondurans so susceptible to human trafficking. “It’s like Russian roulette,” Funes says. “I have come to realise that there are many Hondurans who have an eagerness to migrate to the USA, but have ended up staying in countries like El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Belize and have become victims of sexual exploitation, domestic service and forced matrimonies as they flee from gangs and narco-politics. Some of the people who have left come back mutilated because they lose limbs on the trains.”

For those that do make it to the USA, they face discrimination, but at least they have the opportunity for better salaries, with which they can send money to their families struggling back home, Funes says. These remittances play a key role in sustaining the Honduran economy. In May 2018 Hondurans abroad sent back an all-time high of $456.2 million in a single month.

While Funes would like to see more Hondurans stay at home, not only to avoid the very real risks that come with being a migrant, but also to fight for real change, she is all too aware of why people choose instead to leave. “You have to work five times harder than a corrupt individual to be able to sustain yourself and get ahead in Honduras. This economic model displaces the most vulnerable individuals.”

Much of what Funes and her team do over the next year will be geared towards her dream of founding a centre of investigative journalism, including training journalists and students with the help of Factum magazine in El Salvador. “This will bring together many different journalists who want to transform Honduras with investigative journalism,” Funes says.

With a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy, Funes and her team will also work on a project called Sembrando el Periodismo de Investigación en Honduras (Sowing Investigative Journalism In Honduras), which will involve four major investigations over the course of 2019.

“Many of the things that I dreamt of happening one day, in an idealistic way, have become reality, all thanks to Index,” Funes adds. “Solidarity, love and friendship are really the things that can move this world, and that is what Index is made of with all of the support they have extended to me.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1561460137741-61f82764-3b8a-4″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Oct 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Saudi Arabia, Statements

Saudi journalist, Global Opinions columnist for the Washington Post, and former editor-in-chief of Al-Arab News Channel Jamal Khashoggi offers remarks during POMED’s “Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia: A Deeper Look”. March 21, 2018, Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), Washington, DC.

Recognising the fundamental right to express our views, free from repression, we the undersigned civil society organisations call on the international community, including the United Nations, multilateral and regional institutions as well as democratic governments committed to the freedom of expression, to take immediate steps to hold Saudi Arabia accountable for grave human rights violations. The murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul on 2 October is only one of many gross and systematic violations committed by the Saudi authorities inside and outside the country. As the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists approaches on 2 November, we strongly echo calls for an independent investigation into Khashoggi’s murder, in order to hold those responsible to account.

This case, coupled with the rampant arrests of human rights defenders, including journalists, scholars and women’s rights activists; internal repression; the potential imposition of the death penalty on demonstrators; and the findings of the UN Group of Eminent Experts report which concluded that the Coalition, led by Saudi Arabia, have committed acts that may amount to international crimes in Yemen, all demonstrate Saudi Arabia’s record of gross and systematic human rights violations. Therefore, our organisations further urge the UN General Assembly to suspend Saudi Arabia from the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), in accordance with operative paragraph 8 of the General Assembly resolution 60/251.

Saudi Arabia has never had a reputation for tolerance and respect for human rights, but there were hopes that as Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman rolled out his economic plan (Vision 2030), and finally allowed women to drive, there would be a loosening of restrictions on women’s rights, and freedom of expression and assembly. However, prior to the driving ban being lifted in June, women human rights defenders received phone calls warning them to remain silent. The Saudi authorities then arrested dozens of women’s rights defenders (both female and male) who had been campaigning against the driving ban. The Saudi authorities’ crackdown against all forms of dissent has continued to this day.

Khashoggi criticised the arrests of human rights defenders and the reform plans of the Crown Prince, and was living in self-imposed exile in the US. On 2 October 2018, Khashoggi went to the Consulate in Istanbul with his fiancée to complete some paperwork, but never came out. Turkish officials soon claimed there was evidence that he was murdered in the Consulate, but Saudi officials did not admit he had been murdered until more than two weeks later.

It was not until two days later, on 20 October, that the Saudi public prosecution’s investigation released findings confirming that Khashoggi was deceased. Their reports suggested that he died after a “fist fight” in the Consulate, and that 18 Saudi nationals have been detained. King Salman also issued royal decrees terminating the jobs of high-level officials, including Saud Al-Qahtani, an advisor to the royal court, and Ahmed Assiri, deputy head of the General Intelligence Presidency. The public prosecution continues its investigation, but the body has not been found.

Given the contradictory reports from Saudi authorities, it is essential that an independent international investigation is undertaken.

On 18 October, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called on Turkey to request that UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres establish a UN investigation into the extrajudicial execution of Khashoggi.

On 15 October 2018, David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression, and Dr. Agnès Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on summary executions, called for “an independent investigation that could produce credible findings and provide the basis for clear punitive actions, including the possible expulsion of diplomatic personnel, removal from UN bodies (such as the Human Rights Council), travel bans, economic consequences, reparations and the possibility of trials in third states.”

We note that on 27 September, Saudi Arabia joined consensus at the UN HRC as it adopted a new resolution on the safety of journalists (A/HRC/Res/39/6). We note the calls in this resolution for “impartial, thorough, independent and effective investigations into all alleged violence, threats and attacks against journalists and media workers falling within their jurisdiction, to bring perpetrators, including those who command, conspire to commit, aid and abet or cover up such crimes to justice.” It also “[u]rges the immediate and unconditional release of journalists and media workers who have been arbitrarily arrested or arbitrarily detained.”

Khashoggi had contributed to the Washington Post and Al-Watan newspaper, and was editor-in-chief of the short-lived Al-Arab News Channel in 2015. He left Saudi Arabia in 2017 as arrests of journalists, writers, human rights defenders and activists began to escalate. In his last column published in the Washington Post, he criticised the sentencing of journalist Saleh Al-Shehi to five years in prison in February 2018. Al-Shehi is one of more than 15 journalists and bloggers who have been arrested in Saudi Arabia since September 2017, bringing the total of those in prison to 29, according to RSF, while up to 100 human rights defenders and possibly thousands of activists are also in detention according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) and Saudi partners including ALQST. Many of those detained in the past year had publicly criticised reform plans related to Vision 2030, noting that women would not achieve economic equality merely by driving.

Another recent target of the crackdown on dissent is prominent economist Essam Al-Zamel, an entrepreneur known for his writing about the need for economic reform. On 1 October 2018, the Specialised Criminal Court (SCC) held a secret session during which the Public Prosecution charged Al-Zamel with violating the Anti Cyber Crime Law by “mobilising his followers on social media.” Al-Zamel criticised Vision 2030 on social media, where he had one million followers. Al-Zamel was arrested on 12 September 2017 at the same time as many other rights defenders and reformists.

The current unprecedented targeting of women human rights defenders started in January 2018 with the arrest of Noha Al-Balawi due to her online activism in support of social media campaigns for women’s rights such as (#Right2Drive) or against the male guardianship system (#IAmMyOwnGuardian). Even before that, on 10 November 2017, the SCC in Riyadh sentenced Naimah Al-Matrod to six years in jail for her online activism.

The wave of arrests continued after the March session of the HRC and the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) published its recommendations on Saudi Arabia. Loujain Al-Hathloul, was abducted in the Emirates and brought to Saudi Arabia against her will on 15 May 2018; followed by the arrest of Dr. Eman Al-Nafjan, founder and author of the Saudiwoman’s Weblog, who had previously protested the driving ban; and Aziza Al-Yousef, a prominent campaigner for women’s rights.

Four other women’s human rights defenders who were arrested in May 2018 include Dr. Aisha Al-Manae, Dr. Hessa Al-Sheikh and Dr. Madeha Al-Ajroush, who took part in the first women’s protest movement demanding the right to drive in 1990; and Walaa Al-Shubbar, a young activist well-known for her campaigning against the male guardianship system. They are all academics and professionals who supported women’s rights and provided assistance to survivors of gender-based violence. While they have since been released, all four women are believed to be still facing charges.

On 6 June 2018, journalist, editor, TV producer and woman human rights defender Nouf Abdulaziz was arrested after a raid on her home. Following her arrest, Mayya Al-Zahrani published a letter from Abdulaziz, and was then arrested herself on 9 June 2018, for publishing the letter.

On 27 June 2018, Hatoon Al-Fassi, a renowned scholar, and associate professor of women’s history at King Saud University, was arrested. She has long been advocating for the right of women to participate in municipal elections and to drive, and was one of the first women to drive the day the ban was lifted on 24 June 2018.

Twice in June, UN special procedures called for the release of women’s rights defenders. On 27 June 2018, nine independent UN experts stated, “In stark contrast with this celebrated moment of liberation for Saudi women, women’s human rights defenders have been arrested and detained on a wide scale across the country, which is truly worrying and perhaps a better indication of the Government’s approach to women’s human rights.” They emphasised that women human rights defenders “face compounded stigma, not only because of their work as human rights defenders, but also because of discrimination on gender grounds.”

Nevertheless, the arrests of women human rights defenders continued with Samar Badawi and Nassima Al-Sadah on 30 July 2018. They are being held in solitary confinement in a prison that is controlled by the Presidency of State Security, an apparatus established by order of King Salman on 20 July 2017. Badawi’s brother Raif Badawi is currently serving a 10-year prison sentence for his online advocacy, and her former husband Waleed Abu Al-Khair, is serving a 15-year sentence. Abu Al-Khair, Abdullah Al-Hamid, and Mohammad Fahad Al-Qahtani (the latter two are founding members of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association – ACPRA) were jointly awarded the Right Livelihood Award in September 2018. Yet all of them remain behind bars.

Relatives of other human rights defenders have also been arrested. Amal Al-Harbi, the wife of prominent activist Fowzan Al-Harbi, was arrested by State Security on 30 July 2018 while on the seaside with her children in Jeddah. Her husband is another jailed member of ACPRA. Alarmingly, in October 2018, travel bans were imposed against the families of several women’s rights defenders, such as Aziza Al-Yousef, Loujain Al-Hathloul and Eman Al-Nafjan.

In another alarming development, at a trial before the SCC on 6 August 2018, the Public Prosecutor called for the death penalty for Israa Al-Ghomgam who was arrested with her husband Mousa Al-Hashim on 6 December 2015 after they participated in peaceful protests in Al-Qatif. Al-Ghomgam was charged under Article 6 of the Cybercrime Act of 2007 in connection with social media activity, as well as other charges related to the protests. If sentenced to death, she would be the first woman facing the death penalty on charges related to her activism. The next hearing is scheduled for 28 October 2018.

The SCC, which was set up to try terrorism cases in 2008, has mostly been used to prosecute human rights defenders and critics of the government in order to keep a tight rein on civil society.

On 12 October 2018, UN experts again called for the release of all detained women human rights defenders in Saudi Arabia. They expressed particular concern about Al-Ghomgam’s trial before the SCC, saying, “Measures aimed at countering terrorism should never be used to suppress or curtail human rights work.” It is clear that the Saudi authorities have not acted on the concerns raised by the special procedures – this non-cooperation further brings their membership on the HRC into disrepute.

Many of the human rights defenders arrested this year have been held in incommunicado detention with no access to families or lawyers. Some of them have been labelled traitors and subjected to smear campaigns in the state media, escalating the possibility they will be sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Rather than guaranteeing a safe and enabling environment for human rights defenders at a time of planned economic reform, the Saudi authorities have chosen to escalate their repression against any dissenting voices.

Our organisations reiterate our calls to the international community to hold Saudi Arabia accountable and not allow impunity for human rights violations to prevail.

We call on the international community, and in particular the UN, to:

- Take action to ensure there is an international, impartial, prompt, thorough, independent and effective investigation into the murder of journalist Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi;

- Ensure Saudi Arabia be held accountable for the murder of Khashoggi and for its systematic violations of human rights;

- Call a Special Session of the Human Rights Council on the recent wave of arrests and attacks against journalists, human rights defenders and other dissenting voices in Saudi Arabia;

- Take action at the UN General Assembly to suspend Saudi Arabia’s membership of the Human Rights Council; and

- Urge the government of Saudi Arabia to implement the below recommendations.

We call on the authorities in Saudi Arabia to:

- Produce the body of Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi and invite independent international experts to oversee investigations into his murder; cooperate with all UN mechanisms; and ensure that those responsible for his death, including those who hold command responsibility, are brought to justice;

- Immediately quash the convictions of all human rights defenders, including women and men advocating for gender equality, and drop all charges against them;

- Immediately and unconditionally release all human rights defenders, writers, journalists and prisoners of conscience in Saudi Arabia whose detention is a result of their peaceful and legitimate work in the promotion and protection of human rights including women’s rights;

- Institute a moratorium on the death penalty; including as punishment for crimes related to the exercise of rights to freedom of opinion and expression, and peaceful assembly;

- Guarantee in all circumstances that all human rights defenders and journalists in Saudi Arabia are able to carry out their legitimate human rights activities and public interest reporting without fear of reprisal;

- Immediately implement the recommendations made by the UN Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen; and

- Ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and bring all national laws limiting the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association into compliance with international human rights standards.

Signed,

Access Now

Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) – France

Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) – Germany

Al-Marsad – Syria

ALQST for Human Rights

ALTSEAN-Burma

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Amman Center for Human Rights Studies (ACHRS) – Jordan

Amman Forum for Human Rights

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Armanshahr/OPEN ASIA

ARTICLE 19

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

Asociación Libre de Abogadas y Abogados (ALA)

Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE)

Association for Human Rights in Ethiopia (AHRE)

Association malienne des droits de l’Homme (AMDH)

Association mauritanienne des droits de l’Homme (AMDH)

Association nigérienne pour la défense des droits de l’Homme (ANDDH)

Association of Tunisian Women for Research on Development

Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID)

Awan Awareness and Capacity Development Organization

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law – Tajikistan

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO)

Canadian Center for International Justice

Caucasus Civil Initiatives Center (CCIC)

Center for Civil Liberties – Ukraine

Center for Prisoners’ Rights

Center for the Protection of Human Rights “Kylym Shamy” – Kazakhstan

Centre oecuménique des droits de l’Homme (CEDH) – Haïti

Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos (EQUIDAD) – Perú

Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos (CALDH) – Guatemala

Citizen Center for Press Freedom

Citizens’ Watch – Russia

CIVICUS

Civil Society Institute (CSI) – Armenia

Code Pink

Columbia Law School Human Rights Clinic

Comité de acción jurídica (CAJ) – Argentina

Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos (CEDHU) – Ecuador

Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos – Dominican Republic

Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) -Northern Ireland

Committee to Protect Journalists

Committee for Respect of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia

Damascus Center for Human Rights in Syria

Danish PEN

DITSHWANELO – The Botswana Center for Human Rights

Dutch League for Human Rights (LvRM)

Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center – Azerbaijan

English PEN

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR)

FIDH within the framework of the Observatory for the protection of human rights defenders

Finnish League for Human Rights

Freedom Now

Front Line Defenders

Fundación regional de asesoría en derechos humanos (INREDH) – Ecuador

Foundation for Human Rights Initiative (FHRI) – Uganda

Global Voices Advox

Groupe LOTUS (RDC)

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Hellenic League for Human Rights (HLHR)

Human Rights Association (IHD) – Turkey

Human Rights Center (HRCIDC) – Georgia

Human Rights Center “Viasna” – Belarus

Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

Human Rights Concern (HRCE) – Eritrea

Human Rights in China

Human Rights Center Memorial

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan”

Human Rights Sentinel

IFEX

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression (IFoX) – Turkey

Institut Alternatives et Initiatives citoyennes pour la Gouvernance démocratique (I-AICGD) – DR Congo

International Center for Supporting Rights and Freedoms (ICSRF) – Switzerland

Internationale Liga für Menscherechte

International Human Rights Organisation “Fiery Hearts Club” – Uzbekistan

International Legal Initiative (ILI) – Kazakhstan

International Media Support (IMS)

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

International Press Institute

International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Internet Law Reform and Dialogue (iLaw)

Iraqi Association for the Defense of Journalists’ Rights

Iraqi Hope Association

Italian Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Justice for Iran

Karapatan – Philippines

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

Khiam Rehabilitation Center for Victims of Torture

KontraS

Latvian Human Rights Committee

Lao Movement for Human Rights

Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

League for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran (LDDHI)

Legal Clinic “Adilet” – Kyrgyzstan

Ligue algérienne de défense des droits de l’Homme (LADDH)

Ligue centrafricaine des droits de l’Homme

Ligue des droits de l’Homme (LDH) Belgium

Ligue des Electeurs (LE) – DRC

Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l’Homme (LIDHO)

Ligue sénégalaise des droits humains (LSDH)

Ligue tchadienne des droits de l’Homme (LTDH)

Maison des droits de l’Homme (MDHC) – Cameroon

Maharat Foundation

MARUAH – Singapore

Middle East and North Africa Media Monitoring Observatory

Monitoring Committee on Attacks on Lawyers, International Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL)

Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos (MNDH) – Brasil

Muslims for Progressive Values

Mwatana Organization for Human Rights

National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists

No Peace Without Justice

Norwegian PEN

Odhikar

Open Azerbaijan Initiative

Organisation marocaine des droits humains (OMDH)

People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD)

People’s Watch

PEN America

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN Lebanon

PEN Québec

Promo-LEX – Moldova

Public Foundation – Human Rights Center “Kylym Shamy” – Kyrgyzstan

Rafto Foundation for Human Rights

RAW in WAR (Reach All Women in War)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Right Livelihood Award Foundation

Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights

Sahrawi Media Observatory to document human rights violations

SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights (SALAM DHR)

Scholars at Risk (SAR)

Sham Center for Democratic Studies and Human Rights in Syria

Sisters’ Arab Forum for Human Rights (SAF) – Yemen

Solicitors International Human Rights Group

Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM)

Tanmiea – Iraq

Tunisian Association to Defend Academic Values

Tunisian Association to Defend Individual Rights

Tunisian Association of Democratic Women

Tunis Center for Press Freedom

Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights

Tunisian League to Defend Human Rights

Tunisian Organization against Torture

Urgent Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights (UAF)

Urnammu

Vietnam Committee on Human Rights

Vigdis Freedom Foundation

Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition

Women’s Center for Culture & Art – United Kingdom

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) within the framework of the Observatory for the protection of human rights defenders

Yemen Center for Human Rights

Zimbabwe Human Rights Association (ZimRights)

17Shubat For Human Rights

29 Aug 2018 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95198″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]For the second time since 2013, the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) has issued an Opinion regarding the legality of the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab under international human rights law.

In its second opinion, the WGAD held that the detention was not only arbitrary but also discriminatory. The 127 signatory human rights groups welcome this landmark opinion, made public on 13 August 2018, recognising the role played by human rights defenders in society and the need to protect them. We call upon the Bahraini Government to immediately release Nabeel Rajab in accordance with this latest request.

In its Opinion (A/HRC/WGAD/2018/13), the WGAD considered that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajabcontravenes Articles 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Articles 2, 9, 10, 14, 18, 19 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Bahrain in 2006. The WGAD requested the Government of Bahrain to “release Mr. Rajab immediately and accord him an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations, in accordance with international law.”

This constitutes a landmark opinion as it recognises that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab – President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), Founding Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), Deputy Secretary General of FIDH and a member of the Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa Advisory Committee – is arbitrary and in violation of international law, as it results from his exercise of the right to freedom of opinion and expression as well as freedom of thought and conscience, and furthermore constitutes “discrimination based on political or other opinion, as well as on his status as a human rights defender.” Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention has therefore been found arbitrary under both categories II and V as defined by the WGAD.

Mr. Nabeel Rajab was arrested on 13 June 2016 and has been detained since then by the Bahraini authorities on several freedom of expression-related charges that inherently violate his basic human rights. On 15 January 2018, the Court of Cassation upheld his two-year prison sentence, convicting him of “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in the Kingdom, which undermines state prestige and status” – in reference to television interviews he gave in 2015 and 2016. Most recently on 5 June 2018, the Manama Appeals Court upheld his five years’ imprisonment sentence for “disseminating false rumors in time of war”; “offending a foreign country” – in this case Saudi Arabia; and for “insulting a statutory body”, in reference to comments made on Twitter in March 2015 regarding alleged torture in Jaw prison and criticising the killing of civilians in the Yemen conflict by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition. The Twitter case will next be heard by the Court of Cassation, the final opportunity for the authorities to acquit him.

The WGAD underlined that “the penalisation of a media outlet, publishers or journalists solely for being critical of the government or the political social system espoused by the government can never be considered to be a necessary restriction of freedom of expression,” and emphasised that “no such trial of Mr. Rajab should have taken place or take place in the future.” It added that the WGAD “cannot help but notice that Mr. Rajab’s political views and convictions are clearly at the centre of the present case and that the authorities have displayed an attitude towards him that can only be characterised as discriminatory.” The WGAD added that several cases concerning Bahrain had already been brought before it in the past five years, in which WGAD “has found the Government to be in violation of its human rights obligations.” WGAD added that “under certain circumstances, widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of the rules of international law may constitute crimes against humanity.”

Indeed, the list of those detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion in Bahrain is long and includes several prominent human rights defenders, notably Mr. Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Dr.Abduljalil Al-Singace and Mr. Naji Fateel – whom the WGAD previously mentioned in communications to the Bahraini authorities.

Our organisations recall that this is the second time the WGAD has issued an Opinion regarding Mr. Nabeel Rajab. In its Opinion A/HRC/WGAD/2013/12adopted in December 2013, the WGAD already classified Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention as arbitrary as it resulted from his exercise of his universally recognised human rights and because his right to a fair trial had not been guaranteed (arbitrary detention under categories II and III as defined by the WGAD).The fact that over four years have passed since that opinion was issued, with no remedial action and while Bahrain has continued to open new prosecutions against him and others, punishing expression of critical views, demonstrates the government’s pattern of disdain for international human rights bodies.

To conclude, our organisations urge the Bahrain authorities to follow up on the WGAD’s request to conduct a country visit to Bahrain and to respect the WGAD’s opinion, by immediately and unconditionally releasing Mr. Nabeel Rajab, and dropping all charges against him. In addition, we urge the authorities to release all other human rights defenders arbitrarily detained in Bahrain and to guarantee in all circumstances their physical and psychological health.

This statement is endorsed by the following organisations:

1- ACAT Germany – Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture

2- ACAT Luxembourg

3- Access Now

4- Acción Ecológica (Ecuador)

5- Americans for Human Rights and Democracy in Bahrain – ADHRB

6- Amman Center for Human Rights Studies – ACHRS (Jordania)

7- Amnesty International

8- Anti-Discrimination Center « Memorial » (Russia)

9- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information – ANHRI (Egypt)

10- Arab Penal Reform Organisation (Egypt)

11- Armanshahr / OPEN Asia (Afghanistan)

12- ARTICLE 19

13- Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos – APRODEH (Peru)

14- Association for Defense of Human Rights – ADHR

15- Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression – AFTE (Egypt)

16- Association marocaine des droits humains – AMDH

17- Bahrain Center for Human Rights

18- Bahrain Forum for Human Rights

19- Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy – BIRD

20- Bahrain Interfaith

21- Cairo Institute for Human Rights – CIHRS

22- CARAM Asia (Malaysia)

23- Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

24- Center for Constitutional Rights (USA)

25- Center for Prisoners’ Rights (Japan)

26- Centre libanais pour les droits humains – CLDH

27- Centro de Capacitación Social de Panama

28- Centro de Derechos y Desarrollo – CEDAL (Peru)

29- Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales – CELS (Argentina)

30- Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos – Perú EQUIDAD

31- Centro Nicaragüense de Derechos Humanos – CENIDH (Nicaragua)

32- Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos – CALDH (Guatemala)

33- Citizen Watch (Russia)

34- CIVICUS : World Alliance for Citizen Participation

35- Civil Society Institute – CSI (Armenia)

36- Colectivo de Abogados « José Alvear Restrepo » (Colombia)

37- Collectif des familles de disparu(e)s en Algérie – CFDA

38- Comisión de Derechos Humanos de El Salvador – CDHES

39- Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos – CEDHU (Ecuador)

40- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (Costa Rica)

41- Comité de Acción Jurídica – CAJ (Argentina)

42- Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos – CPDH (Colombia)

43- Committee for the Respect of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia – CRLDHT

44- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative – CHRI (India)

45- Corporación de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos del Pueblo – CODEPU (Chile)

46- Dutch League for Human Rights – LvRM

47- European Center for Democracy and Human Rights – ECDHR (Bahrain)

48- FEMED – Fédération euro-méditerranéenne contre les disparitions forcées

49- FIDH, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

50- Finnish League for Human Rights

51- Foundation for Human Rights Initiative – FHRI (Uganda)

52- Front Line Defenders

53- Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos – INREDH (Ecuador)

54- Groupe LOTUS (DRC)

55- Gulf Center for Human Rights

56- Human Rights Association – IHD (Turkey)

57- Human Rights Association for the Assistance of Prisoners (Egypt)

58- Human Rights Center – HRIDC (Georgia)

59- Human Rights Center « Memorial » (Russia)

60- Human Rights Center « Viasna » (Belarus)

61- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

62- Human Rights Foundation of Turkey

63- Human Rights in China

64- Human Rights Mouvement « Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan »

65- Human Rights Sentinel (Ireland)

66- Human Rights Watch

67- I’lam – Arab Center for Media Freedom, Development and Research

68- IFEX

69- IFoX Turkey – Initiative for Freedom of Expression

70- Index on Censorship

71- International Human Rights Organisation « Club des coeurs ardents » (Uzbekistan)

72- International Legal Initiative – ILI (Kazakhstan)

73- Internet Law Reform Dialogue – iLaw (Thaïland)

74- Institut Alternatives et Initiatives Citoyennes pour la Gouvernance Démocratique – I-AICGD (RDC)

75- Instituto Latinoamericano para una Sociedad y Derecho Alternativos – ILSA (Colombia)

76- Internationale Liga für Menschenrechte (Allemagne)

77- International Service for Human Rights – ISHR

78- Iraqi Al-Amal Association

79- Jousor Yemen Foundation for Development and Humanitarian Response

80- Justice for Iran

81- Justiça Global (Brasil)

82- Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

83- Latvian Human Rights Committee

84- Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

85- League for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran

86- League for the Defense of Human Rights – LADO Romania

87- Legal Clinic « Adilet » (Kyrgyzstan)

88- Liga lidských práv (Czech Republic)

89- Ligue burundaise des droits de l’Homme – ITEKA (Burundi)

90- Ligue des droits de l’Homme (Belgique)

91- Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l’Homme

92- Ligue sénégalaise des droits humains – LSDH

93- Ligue tchadienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

94- Ligue tunisienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

95- MADA – Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedom

96- Maharat Foundation (Lebanon)

97- Maison des droits de l’Homme du Cameroun – MDHC

98- Maldivian Democracy Network

99- MARCH Lebanon

100- Media Association for Peace – MAP (Lebanon)

101- MENA Monitoring Group

102- Metro Center for Defending Journalists’ Rights (Iraqi Kurdistan)

103- Monitoring Committee on Attacks on Lawyers – International Association of People’s Lawyers

104- Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos – MNDH (Brasil)

105- Mwatana Organisation for Human Rights (Yemen)

106- Norwegian PEN

107- Odhikar (Bangladesh)

108- Pakistan Press Foundation

109- PEN America

110- PEN Canada

111- PEN International

112- Promo-LEX (Moldova)

113- Public Foundation – Human Rights Center « Kylym Shamy » (Kyrgyzstan)

114- RAFTO Foundation for Human Rights

115- Réseau Doustourna (Tunisia)

116- SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights

117- Scholars at Risk

118- Sisters’ Arab Forum for Human Rights – SAF (Yemen)

119- Suara Rakyat Malaysia – SUARAM

120- Taïwan Association for Human Rights – TAHR

121- Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights – FTDES

122- Vietnam Committee for Human Rights

123- Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

124- World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers – WAN-IFRA

125- World Organisation Against Torture – OMCT, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

126- Yemen Organisation for Defending Rights and Democratic Freedoms

127- Zambia Council for Social Development – ZCSD[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1535551119543-359a0849-e6f7-3″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jul 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

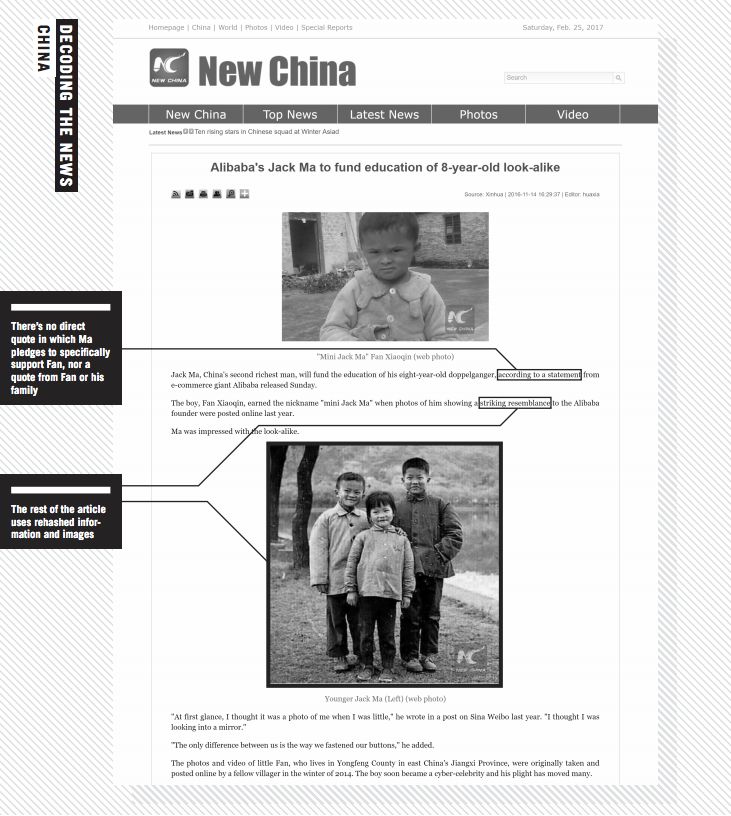

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

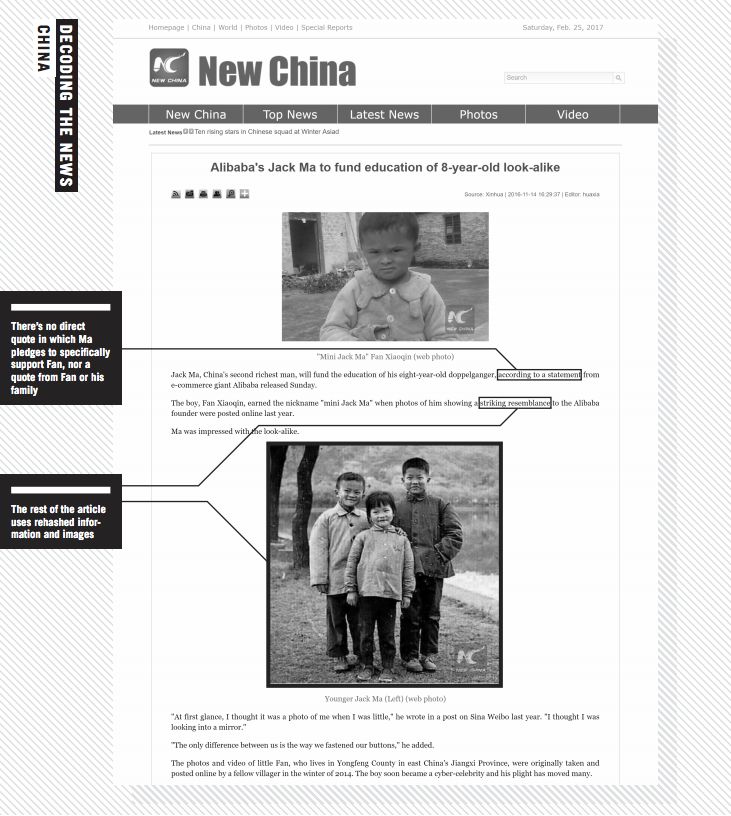

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

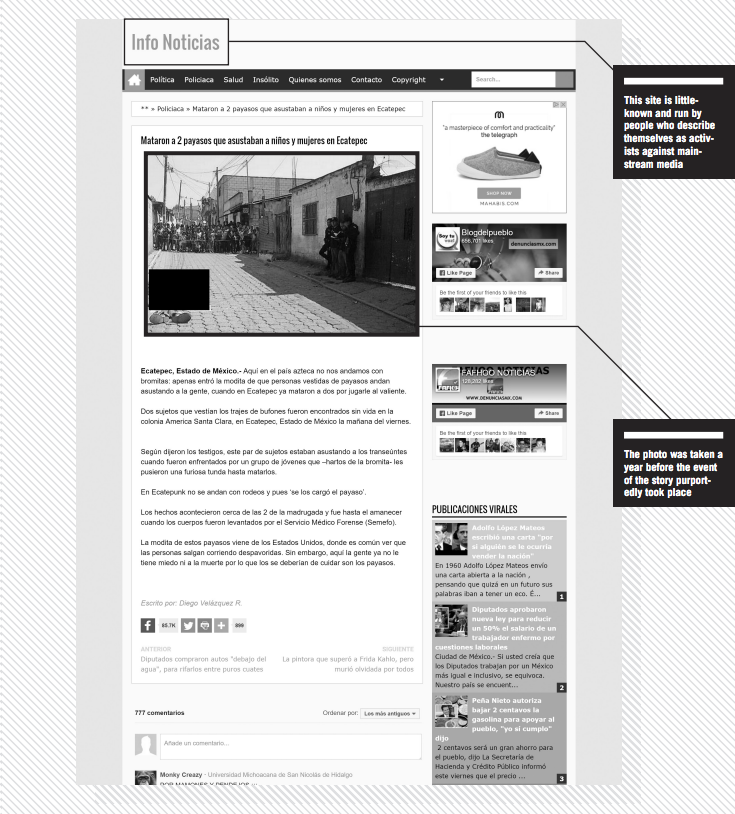

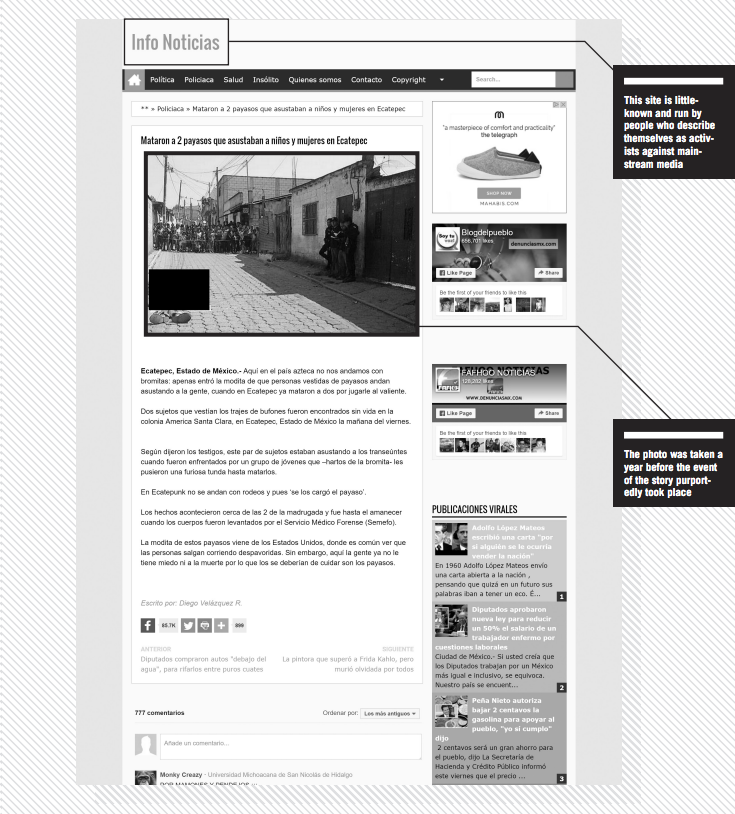

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

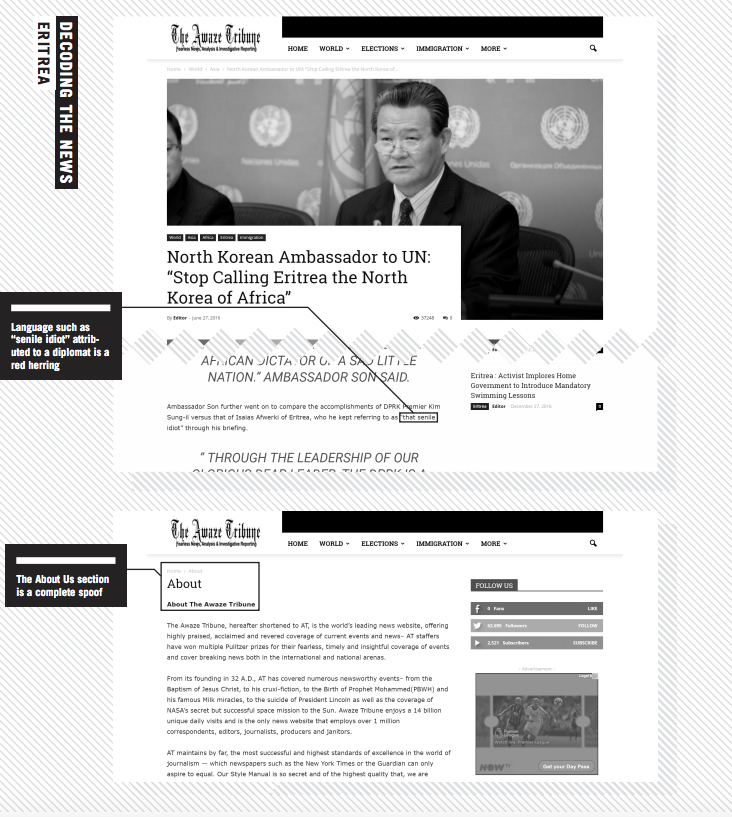

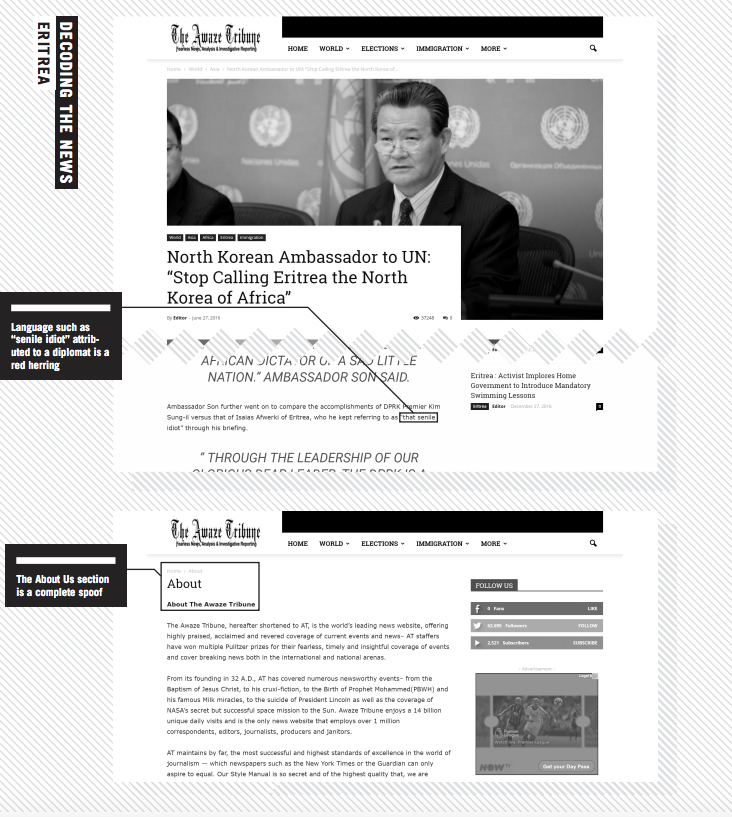

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

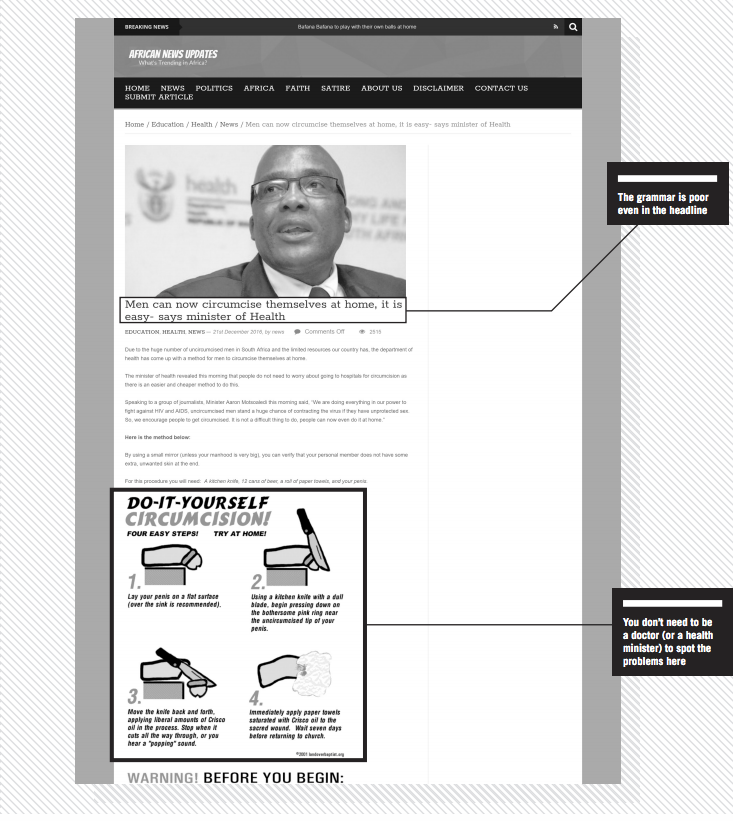

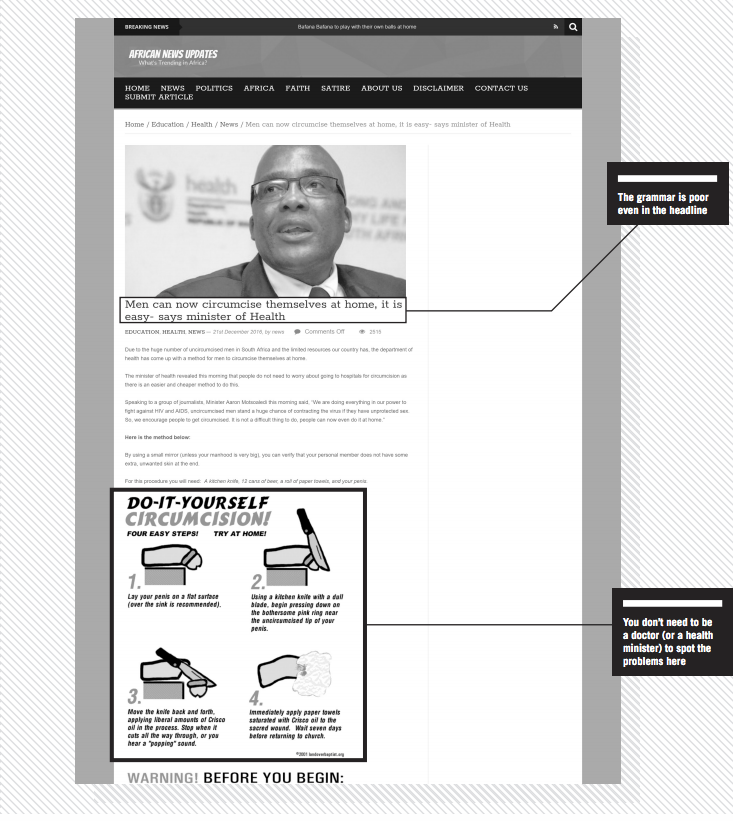

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]