Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

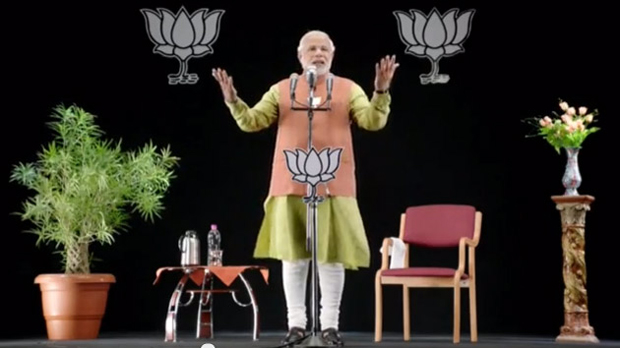

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The Global Network Initiative (GNI) and the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMA) have launched an interactive slide show exploring how India’s internet and technology laws are holding back economic innovation and freedom of expression.

India, which represents the third largest population of internet users in the world, is at crossroads: while the country protects free speech in its constitution, restrictive laws have undermined Indias record on freedom of expression.

Constraints on digital freedom have caused much controversy and debate in India, and some of the biggest web host companies, such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook, have faced court cases and criminal charges for failing to remove what is deemed objectionable content. The main threat to free expression online in India stems from specific laws: most notorious among them the 2000 Information Technology Act (IT Act) and its post-Mumbai attack amendments in 2008 that introduced new regulations around offence and national security.

In November 2013, Index launched a report exploring the main challenges and threats to online freedom of expression in India, including takedown, filtering and blocking policies, and the criminalisation of online speech.

This article was posted on Aug 1, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

A month has passed since Narendra Modi became prime minister of India, and brought the right wing Hindu nationalist BJP (Bharatiya Janta Party) back into power. Much has been written about his government, with observers either hailing him as an economic messiah who will fix India’s dwindling economy or a divisive politician who has built his career on the back of communalism.

Those watching freedoms, especially of free speech and the media, are among the people apprehensive about life under Modi’s government. While the prime minister himself has blogged about the importance of free expression, recent arrests, including of citizens directly critical of him, paint a worrying picture. Additionally, the rise of “communal posts” on social media, real or planed, have lead to violence on the ground, and a debate about how best to police social media and free speech online.

In June, a young Muslim IT graduate lost his life to an angry mob in the city of Pune, Maharashtra, due to violence that erupted after morphed pictures of a historical figure appeared on Facebook and WhatsApp. The pictures were said to be triggers for crowds to damage shops and public transport, ultimately resulting in communal violence and the loss of an innocent life. However, reports from the Anti Terror Squad of the Maharashtra police indicate that the outbreak of violence following the uploaded picture does not seem sporadic or unplanned.

The state government has issued familiar warnings about the misuse of social media by groups that are looking to incite communal tension. Home Minister, R. R. Patil, was quoted as saying that “anti-social elements are posting inflammatory posts to stoke hatred, bitterness and disharmony between sects”, warning that such posts could result in action not just against those who post the photos, but also those who “like” them. Of course, this was the same state which saw two girls were arrested last year for allegedly sparking communal violence — one for writing a Facebook update, and the other girl simply for “liking” it. Therefore, any action by the government needs to be tempered by what the fallout could be for ordinary citizens and their right to free speech.

But authorities are not alone in seeking a solution to the problem of potentially inflammatory social media postings — civil society groups are also trying novel ideas to counter the trend. Ravi Ghate, a social entrepreneur and founder of a community SMS newsletter in Maharashtra, has banded together with like-minded folks to form a group on Facebook called “Social Peace Force”. Amassing over 18,000 members in ten days, the mission of the group is to “stop anti-social messages on Facebook” by reporting them as spam. “It’s the easiest and technological way to fight the culprits who are spreading anti-national messages/images and stopping ourselves from development!” is the logic the group adheres to. Many of the new members have posted comments indicating their genuine desire to help stop the spread of abusive and communal messages. Therefore, once identified, all members of the group will report a message or posting to Facebook thereby pressurising them to remove the post before it can do any more damage. The group has also instituted a panel of experts who are meant to examine any troubling post and give the go-ahead for the group to act.

What has spurred this move? “How many times can you go to court,” Ghate told Index. “It is too expensive. And the problem is that by the time the police takes down the content, the riot has already taken place.” For them, “suppressing content at the source” in a timely manner is key. A technological solution within the boundaries of Facebook’s own rules of engagement seems to some a far more pragmatic solution than going to the courts again and again.

Seen from a broader lens however, the group’s solution seems to be to shift the onus from the courts to decide the parameters of free expression and “objectionable” content, to big, profit-making, multinational corporates. What might seem today a no-brainer because of some obviously mischievous content, could in time, pose an interesting dilemma: Should social media giants control the boundaries of (social media based) speech in countries such as India, based on their own internal policies, and not the laws of the land? And all this, because of a push by the citizens themselves, to bypass courts and go directly to the corporates.

It is ironic that “Big Brother’ – which is what some newspaper headlines called the group – when translated into Hindi could be interpreted as “elder brother”, indicating a protective instinct, which certainly seems to be the case here. The current mandate of the group is only to focus on religious content to keep “social harmony”. That in itself is not a straightforward task; just ask Wendy Doniger, author of ‘The Hindus: An Alternative History’. However, this and the many spinoff groups they will inspire could morph into something they did not intend. Legitimate art, literature, satire and other forms of expression could become victims of the mob. Then there is danger of more organised groups and political parties taking to social media directly to suppress content — especially political critique — on a regular basis. And finally, those who wish to subvert social media platforms to have an excuse to incite violence on the street, will certainly find more creative ways to do so.

There is of course, the other side of the coin. Will Facebook remove content that has been pre-determined to be objectionable when faced with a large number of people reporting it? The simple answer is, we don’t know. Facebook has its own community standards, and these cover a broad range of topics, including the following: “Facebook does not permit hate speech, but distinguishes between serious and humorous speech. While we encourage you to challenge ideas, institutions, events, and practices, we do not permit individuals or groups to attack others based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, disability or medical condition.”

And a recent experiment by an Indian think-tank revealed that Facebook did not necessarily remove content flagged as objectionable by users, solely on the basis of it being flagged. As Facebook told them: “We reviewed the post you reported for harassment and found it doesn’t violate our Community Standards.” It is quite possible that the newly formed Social Peace Force will feel let down by Facebook as well, if content is not removed immediately. What happens then?

However, this latest development harks back to the problems with India’s current legal mechanisms. India’s IT Act has become infamous for a certain Section 66(A) which can be used to arrest people for information used for the purposes of “annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will”. Public outrage at wrongful arrests led to the courts passing an order that no person would be arrested without “prior approval from an officer not below the rank of inspector general of police”. At the same time, the establishment is not above slapping graver charges (such as inciting communal violence) under other sections of Indian law — including the Indian Penal Code — for fairly innocuous activity. This has lead to some amount of distrust at the government’s own commitment to freedom of expression.

Of course, citizens have a right to appeal to social media platforms if they take offense to any content posted there. The point remains, however, that maintaining communal harmony and law and order is a tricky and layered problem. The role of the state, and the loss of confidence citizens have in it, must be addressed as well. Earlier solutions have included the state governments of Jammu and Kashmir preempting violence by switching off social media and YouTube for a few days, in the wake of burgeoning riots around the world because of the video “The Innocence of Muslims”. At another time, the government of India restricted text messages to five a day to curtail vicious rumours targeting a minority community settled in south India. India’s National Integration Council met in September 2013 after social media posts had been blamed for causing riots in Uttar Pradesh, and many states are setting up social media monitoring departments to raise “red flags”, much like the Social Peace Force itself.

A coherent and honest study of the abuse of social media platforms by fringe groups to incite violence should take place. Given the fast paced nature of the medium, the question for a country as prone to communal riots as India is: how can one control them? Is counter-speech to drown out hate speech a strategy to be employed? Is clamping down on free speech effectively going to reduce religious intolerance? Does bypassing legal routes and going straight to the “source” help? A national dialogue on the matter might be more fruitful in the long run than the flowering of surveillance groups cutting across the board — be they citizen or state-led.

This article was published on June 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Volunteers put on a puppet show to teach rural people about the CGNet Swara project (Image: Purushottam Thakur)

Three months after winning the Index Digital Activism Award for his work with CGNet Swara, Shubhranshu Choudhary spoke to Index about his most recent project, teaching rural villagers through performing arts how their mobile phones can be used to report incidents and issues that may otherwise be given the cold-shoulder by the authorities.

CGNet Swara (Voice of Chhattisgarh) is a mobile phone service that allows citizens to upload and listen to reports in their local language without the need for a smartphone or an internet connection.

The new experiment, as Choudhary referred to it, ran for a month, from 15 May to 15 June, and included volunteer artists performing in market places and villages in six of India’s 29 states. During this time the average number of daily reports jumped from 500 to 800, although, as Choudhary pointed out, it is too early tell if this was just an anomaly.

The team involved flipped their conventional method of teaching on its head. Previously, rural people were brought to the cities where they sat in classrooms and lectured about how to use the service. By physically going to the villagers instead, CGNet Swara has “reversed the order”, now teaching people in a way that makes them feel comfortable.

“We have made dance, we have written songs about our work, we have made a small drama, and there are characters that are puppets,” Choudhary told Index. “So in an entertaining way we try to tell them the problems with current mainstream media, which everyone should have equal access to, but unfortunately is owned and controlled by a small number of rich people.” This has resulted in a media full of information about the rich, according to Choudhary, with 80% of the population only receiving about 20% news coverage.

Between five and six million people speak Gondi in the six states CGNet Swara has visited, but they lack their own communication platform, with no radio station, newspaper or TV channel available in the Gondi language. CGNet Swara allows people to report incidents and get their voices heard when they might otherwise have been shunned.

Choudary was clear to point out that the people for whom this service is most vital are not uneducated, but rather a huge number of them live in rural areas and “feel more comfortable listening and speaking rather than reading and writing”. In a country where most Indians don’t have access to the internet but over 70% have access to a mobile phone, services like CGNet Swara play a pivotal part in giving the majority of the population a voice.

“By improving your communication platform, by improving the structure of communication within a community, by improving it from a top-down, one-way communication method to a bottom-up dialogue model of communication we are able to solve many smaller problems,” Choudhary told Index. “And maybe we will be contributing towards solving bigger problems as well.”

So how does CGNet Swara work? The programme allows people to phone in reports in their native language to the service, where they are then verified, translated and made available for playback online as well as over the phone. This is where urban activists come in to play. As Choudhary told Index, these are the people with the connections to the authorities, who speak the right language and can help getting these issues and problems solved. They complete the circle.

After the apparent success of last month’s trial period Choudhary is keen to continue with the project. “From what I gather from everyone, everyone’s pretty excited, but we will need some funding to continue it.” He told Index the project is not cheap to implement but “we are pretty convinced this is the way to reach these people.

“We feel convinced that this is the way to reach that last person of our community, because they are the ones who are left out. They are the ones whose voices are not coming out.”

Listen to the full interview with Shubhranshu Choudhary below.

This article was published on June 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org