11 Sep 2024 | Afghanistan, Albania, Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

A summit on Afghan women’s rights is taking place in the Albanian capital Tirana this week. The gathering comes just two weeks after the Taliban’s “vice and virtue” laws banned women in Afghanistan speaking in public.

The All-Afghan Women’s Summit is in stark contrast to a United Nations meeting in Doha, Qatar at the end of June on the future of Afghanistan which excluded women at the insistence of the Taliban.

Over 100 Afghan women are taking part in the summit in Tirana, which is co-hosted by the governments of Albania and Spain and co-sponsored by the government of Switzerland.

The event is organised by Women for Afghanistan and chaired by Afghan campaigner and former politician Fawzia Koofi. The summit is designed to give a voice to Afghan women and work towards a manifesto for the future of Afghanistan.

Koofi said: “Whilst my sisters have suffered the most under the Taliban, they have also been the strongest voices standing up against oppression. This Summit will bring us together, consolidate our positions, and build unity and purpose towards a common vision for our country. We urge the international community to listen to our recommendations on a unified platform. There is simply no time to lose”.

The occasion was marked by the release of an anthem by the UK-based Aghan singer Elaha Soroor celebrating the strength and resilience of Afghan women. The song is sung to the words of a poem in Farsi based on the rallying cry of the women’s protest movement in Afghanistan: “Bread, Work, Freedom! Education, Work, Freedom!”

“This poem is an expression of a woman’s struggle for autonomy, identity, and liberation from the constraints imposed by tradition and patriarchal authority,” Soror explained. “As the poem progresses, she reclaims her power, embracing her own identity and rejecting patience as a virtue that no longer serves her.”

Index has consistently campaigned for women’s rights in Afghanistan. Since the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, the organisation has put pressure on the British government to honour its promises to Afghan journalists and women.

Three years ago, we helped organise an open letter to The Times calling on the UK government to intervene on behalf of Afghan actors, writers, musicians and film makers targeted by the Taliban. Since then, we have run a series of articles about life under the Taliban regime.

This article from February 2023 was written anonymously about one female journalist who suffered assault and starvation during her escape from Afghanistan. Thankfully, the writer concerned, Spozhmai Maani, is now safely in France, thanks to the support of Index and other international organisations. We were delighted to announce in January 2024 that Spozhmai had won our Moments of Freedom award. Others have not been so fortunate, The crackdown on journalists continues and the latest laws effectively criminalise free expression for women.

3 Jul 2024 | Albania, Europe and Central Asia, Kosovo, News and features, Serbia, Switzerland

Following the controversy of the 2022 World Cup when organising body FIFA faced major criticism over the decision to hold one of the biggest sporting events on the planet in Qatar, a state with a terrible record on human rights, governing body UEFA have attempted to steer clear of any politics whatsoever at this summer’s European Championships.

This year’s competition – which is currently ongoing – has stressed a message of unity, togetherness and inclusion, with UEFA being determined to avoid the negative press garnered by FIFA two years ago by remaining tight-lipped on political issues.

However, no matter how hard you try, politics cannot be removed from football. A number of issues related to freedom of speech have given UEFA headaches during the tournament, showing that censorship can be experienced anywhere, even when you try to avoid it.

One of the most significant examples of free speech being curtailed at the Euro 2024 was the case of Kosovan journalist Arlind Sadiku, who was barred by UEFA from reporting on the remainder of the tournament after he aimed an Albanian eagle sign towards Serbia fans during a broadcast.

Kosovo, Sadiku’s home state, has a population made up of 93% ethnic Albanians and the countries have a strong connection. Serbia does not recognise the independence of Kosovo and there is a history of conflict between the two nations, with relations remaining tense since the end of the brutal Kosovo War in 1999. The eagle symbol made by Sadiku represents the one on Albania’s flag and was deemed by UEFA to be provocative.

Sadiku told the Guardian: “People don’t know how I was feeling in that moment because I have trauma from the war. My house was bombed in the middle of the night when I was a child.

“I know it was unprofessional from a journalist’s perspective, but seeing my family in that situation was traumatic for me and I can’t forget it.”

The conflict between Serbia and Kosovo has caused free speech issues in sport before. In 2021, a Kosovan boxing team was denied entry to Serbia for the AIBA Men’s World Boxing Championships. It was a similar story at the European Under-21 Table Tennis Championships in 2022, which were held in Belgrade, as Kosovo athletes were once again not permitted to participate by Serbian authorities.

Even in football this has been a long-standing issue. At the 2018 World Cup, Swiss duo Xherdan Shaqiri and Granit Xhaka were charged by FIFA for each making the eagle salute after scoring against Serbia for Switzerland. They were each fined £7,600 for their celebrations.

Granit Xhaka’s father spent more than three years as a political prisoner in Yugoslavia due to his support for Kosovan independence and Xherdan Shaqiri came to Switzerland as a refugee and couldn’t go back to visit his family due to the war. Such context was again not enough to mitigate the players’ actions according to FIFA.

Of course, there is an argument to be made that the symbol made by Sadiku, Shaqiri and Xhaka was incendiary and risked provoking aggravation among fans, which could potentially be a safety hazard. However, if those who have personally experienced persecution are then punished when making a peaceful protest, then there is surely no room for any dissent in sport at all.

Many of the other conversations around free speech at Euro 2024 have been centred around nations in the Balkans.

Jovan Surbatovic, general secretary of the Football Association of Serbia, suggested that the country may withdraw from the tournament completely due to hate chants he claimed were made by Croatia and Albania fans. Serbia themselves have been the subject of a number of complaints – they were charged by UEFA after supporters unveiled a banner with a “provocative message unfit for a sports event”, while the Kosovo Football Federation also lodged a complaint about their fans spreading “political, chauvinistic, and racist messages” declaring their supremacy to Kosovo. One Albanian player, Mirlind Daku, was banned for two games for joining in with fans’ anti-Serbia chants after their draw with Croatia.

When nations have such complex relationships and history outside of football it can easily spill out on the pitch. The heightened emotion and passion of sport makes for a compelling watch, but can also increase tensions between nations. In such a convoluted context it is sometimes difficult to know where to draw the line between the right to free speech and the protections against hate speech.

Global conflicts have thrown up more sticking points – when calls were made for Israel to be barred from competing at Euro 2024 due to their ongoing bombardment of Gaza – which has killed more than 37,000 Palestinians – in response to the 7 October attacks by Hamas, UEFA refused. Niv Goldstein, chief executive of the Israel Football Association, told Sky News: “I am trusting Fifa not to involve politics in football. We are against involving politicians in football and being involved in political matters in the sport in general.”

This doesn’t quite match up with the fact that UEFA banned Russia from the competition soon after their invasion of Ukraine, demonstrating the difficulties in finding where to draw the line when attempting to regulate political speech and expression in football. UEFA were spared the headache of dealing with further protest at the tournament after Israel failed to qualify.

Similar issues were raised when German authorities ruled that only flags of participating teams would be allowed into stadiums, which was widely seen as an attempt to avoid potential conflict over Palestine and Israel flags being displayed, but which raised concerns that it would limit support for Ukraine. Blanket bans are often difficult to reconcile with the idea of free speech.

Football can’t ever be fully separated from politics. Just look at the case of Georgian MP Beka Davituliani, who weaponised the country’s shock victory against Portugal in his attempt to roll back on human rights, stating that the country needed defending from so-called LGBTQ+ propaganda like Giorgi Mamardashvili defended his goal. For the most part, fans and players have been able to express themselves freely, but we have a duty to highlight any issues when they arise – and unfortunately, at this summer’s tournament, they have.

11 Jun 2024 | Israel, Moldova, News and features, Russia, Ukraine

Israel’s High Court of Justice this week heard a petition challenging new legislation allowing a ban on foreign broadcasters deemed a threat to national security.

Known as the Al Jazeera law, in honour of its inaugural target, this allows the communications minister, with the consent of the prime minister and the committee of national security, to impose far-reaching sanctions.

“There is no doubt that there is a violation of freedom of expression here,” the High Court panel’s head, Justice Yitzhak Amit, told the hearing.

Yet Israel’s May shuttering of Al Jazeera – described as a “terror channel” by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu – passed without much domestic concern.

Any outrage was limited to Israel’s small liberal left wing, even though in banning Al Jazeera, Israel joins the august ranks of countries including Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Bahrain.

The issue is, of course, rife with politicisation. Al Jazeera is headquartered in Qatar, as is part of the Hamas leadership, and is hardly free from bias. Nonetheless, this law can be used in the future to ban other foreign broadcasters that are deemed to pose an amorphous “threat to national security”.

And crucially, it includes an “override clause” that even Israel’s high court cannot overturn.

It’s important to note that countries often introduce special legislation affecting media in times of war and crisis, amid legitimate national security considerations.

Ukraine is an obvious case in point, not least because it faces such a particularly sharp threat from Russian disinformation.

A year before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, President Volodymyr Zelensky moved to shut down three pro-Russian TV channels judged to effectively be weapons in Russia’s information war.

Immediately after the full-scale invasion, all national news channels were united into a 24-hour broadcast, and a subsequent newly revised media law was intended to be muscular enough to withstand Russian malign influence.

Yet while criticism of the government in times of war – especially one being fought with a citizen’s army – is not easy, Ukrainian journalists have quite effectively held their leaders to account.

Reporting on corruption in the defence ministry, for instance, heralded the minister’s resignation of defence minister Oleskiy Reznikov and government pledges for greater transparency.

And critically, the Government’s moves in the information sphere have not gone unchallenged. Ukraine, with its history of authoritarian government and a media scene under the sway of oligarchs and political interests, knows all too well how fragile free expression can be.

While officials made clear that the telethon would be completely free of government intervention, not all outlets were included, and critics note that some of those excluded such as Espresso, Channel 5, and Priamyi, had often criticised Zelensky and to varying degrees were associated with his predecessor Petro Poroshenko.

And there was widespread criticism of the March 2023 media law for handing too much power to government intervention, with the same measures to counter Russian disinformation all too easily abused to limit critical voices.

In neighbouring Moldova, scores of pro-Russian outlets were banned under the state of emergency declared immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. More than two years later, the TV channels and websites remain blocked despite the end of the state of emergency, and many critics would argue that the country remains as vulnerable as ever to Russian propaganda.

What is needed to ensure that national security considerations do not become a tool to control free expression is a robust civil society push back and an ongoing debate on the boundary between freedom of speech and the fight against fake news.

In Israel, where the national narrative has become an inextricable part of the conflict itself, the public appears increasingly supine in the face of the official version of events.

Israel has long championed its diverse and outspoken media sector as a sign of a vibrant democracy, alongside robust laws that purport to protect free expression. But civil society and media are now experiencing repression from both official and non-state sources, with Palestinian citizens of Israel bearing the brunt.

Anti-war protests have been curtailed and violently repressed; Jewish and Arab teachers fired over left-wing posts on social media, while students have faced disciplinary actions for simply supporting a ceasefire.

Dissenting voices and journalists are being directly targeted and doxxed. Just after 7 October, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi suggested police be empowered to arrest those accused of spreading information that could harm morale or fuel enemy propaganda.

Haaretz journalist Rogel Alpher this week noted a column in Yisrael Hayom which called for articles in the penal law that mandate execution or life imprisonment enforced on those disseminating “defeatist propaganda” or “abetting the enemy”.

Of course, Israel is not about to start executing journalists. The vast majority of extreme proposals do not make it into law, just as most anti-war arrests do not lead to indictments. Even bans on specific outlets are not total; Al Jazeera can still be accessed with absolute ease online.

But this all helps create a chilling atmosphere, serving to normalise such actions and increasing self-censorship.

Israel’s Hebrew-language media has chosen to self-censor to such a large extent that Jewish Israelis experience what Esther Solomon, editor-in-chief of Haaretz English, describes as a “cognitive gap” between the content they consume and what the rest of the world sees.

This means that anything confronting the profoundly uncomfortable reality of war and contradicting the accepted IDF narrative is seen as traitorous and a threat to national security.

The public acceptance of vaguely worded censorious media laws seems to fit all too well with the ongoing slow and creeping deterioration of Israel’s democracy.

31 May 2024 | Israel, News and features, Palestine

The following article was first published by +972 Magazine, an independent, online, nonprofit magazine run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists. Index on Censorship has reported on media freedom on both sides of the conflict since the 7 October attacks.

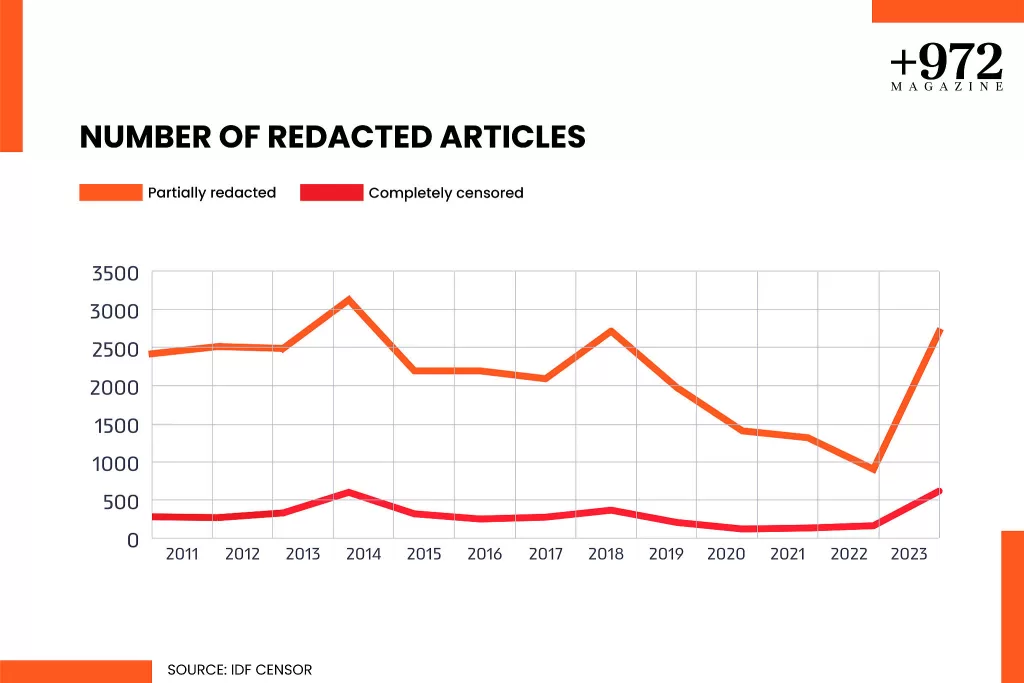

In 2023, the Israeli military censor barred the publication of 613 articles by media outlets in Israel, setting a new record for the period since +972 Magazine began collecting data in 2011. The censor also redacted parts of a further 2,703 articles, representing the highest figure since 2014. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of nine times a day.

This censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information request submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

Israeli law requires all journalists working inside Israel or for an Israeli publication to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication, in line with the “emergency regulations” enacted following Israel’s founding, and which remain in place. These regulations allow the censor to fully or partially redact articles submitted to it, as well as those already published without its review. No other self-proclaimed “Western democracy” operates a similar institution.

To prevent arbitrary or political interference, the High Court ruled in 1989 that the censor is only permitted to intervene when there is a “near certainty that real damage will be caused to the security of the state” by an article’s publication. Nonetheless, the censor’s definition of “security issues” is very broad, detailed across six densely-filled pages of sub-topics concerning the army, intelligence agencies, arms deals, administrative detainees, aspects of Israel’s foreign affairs, and more. Early on in the war, the censor distributed more specific guidance regarding which kinds of news items must be submitted for review before publication, as revealed by The Intercept.

Submissions to the censor are made at the discretion of a publication’s editors, and media outlets are prohibited from revealing the censor’s interference — by marking where an article has been redacted, for instance — which leaves most of its activity in the shadows. The censor has the authority to indict journalists and fine, suspend, shut down, or even file criminal charges against media organizations. There are no known cases of such activity in recent years, however, and our request to the censor to specify its indictments filed in the past year was not answered.

For more background on the Israeli military censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

“Information pertaining to censorship is of particularly high importance, especially in times of emergency,” attorney Or Sadan of the Movement for Freedom of Information told +972. “During the war, we have [witnessed] the large gaps between Israeli and international media outlets, as well as between the traditional media and social media. Although it is obvious that there is information that cannot be disclosed to the public in times of emergency, it is appropriate for the public to be aware of the scope of information hidden from it.

“The significance of such censorship is clear: there is a great deal of information that journalists have seen fit to publish, recognizing its importance to the public, that the censor chose not to allow,” Sadan continued. “We hope and believe that the exposure of these numbers, year after year, will create some deterrence against the unchecked use of this tool.”

A wartime trend

Although the censor refused our request to provide a breakdown of its censorship figures by month, media outlet, and grounds for interference, it is clear that the reason for last year’s spike is the Hamas-led October 7 attack and the ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza. The only year for which there was a comparable level of silencing was 2014, when Israel launched what was then its largest assault on the Strip; that year, the censor intervened in more articles (3,122) but disqualified slightly fewer (597) than in 2023.

Last year, the censor’s representatives also made in-person visits to news studios, as has previously occurred during periods in which the government has declared a state of emergency, and continued monitoring the media and social networks for censorship violations. The censor declined to detail the extent of its involvement in television production and the number of retroactive interventions it made in regard to previously published news articles.

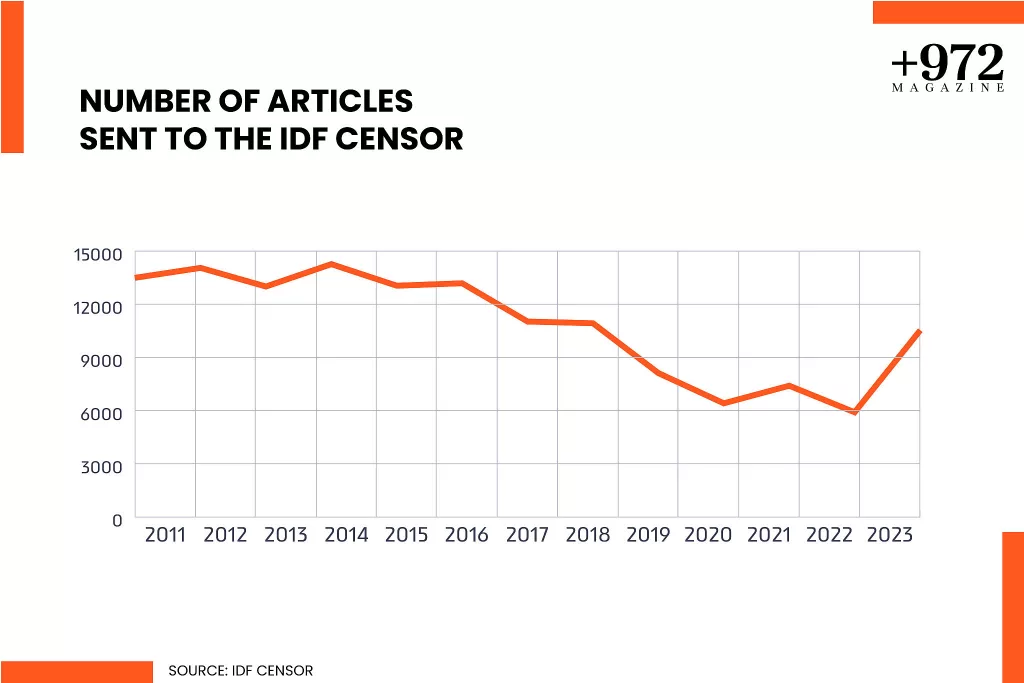

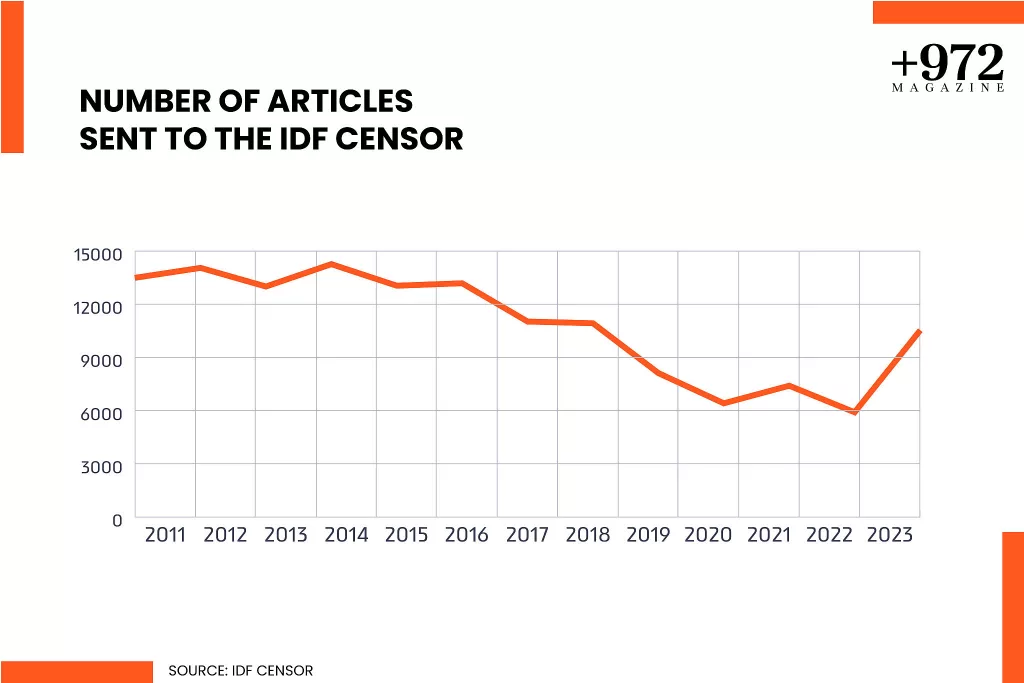

We do know, however, thanks to information revealed by The Seventh Eye, that despite the Israeli media’s proactive compliance — the number of submissions to the censor nearly doubled last year to 10,527 — the censor identified an additional 3,415 news items containing information that should have been submitted for review, and 414 that were published in violation of its orders.

Even before the war, the Israeli government had advanced a series of measures to undermine media independence. This led to Israel dropping 11 places in the 2023 annual World Press Freedom Index, followed by an additional four places in 2024 (it now sits in 101st place out of 180).

Since October, press freedom in Israel has further deteriorated, and the censor has found itself in the crosshairs of political battles. According to reports by Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pushed for a new law that would force the censor to ban news items more widely, and even suggested that journalists who publish reports on the security cabinet without the approval of the censor should be arrested. The chief military censor, Major General Kobi Mandelblit, also claimed that Netanyahu had pressured him to expand media censorship, even in cases that lacked any security justification.

In other cases, the Israeli government’s crackdown on media has skirted the censor and its activities entirely. Back in November, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi banned Al-Mayadeen from being broadcast on Israeli TV, and in April, the Knesset passed a law to ban the activities of foreign media outlets at the recommendation of security agencies. The government implemented the law earlier this month when the cabinet unanimously voted to shut down Al Jazeera in Israel, and the ban will now reportedly also be extended to the West Bank. The state claims that the Qatari channel poses a danger to state security and collaborates with Hamas, which the channel rejects.

The decision will not affect Al Jazeera’s operations outside of Israel, nor will it prevent interviews with Israelis via Zoom (full disclosure: this writer sometimes interviews with Al Jazeera via Zoom), and Israelis can still access the channel via VPN and satellite dishes. But Al Jazeera journalists will no longer be able to report from inside Israel, which will reduce the channel’s ability to highlight Israeli voices in its coverage.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Al Jazeera petitioned the High Court against the decision, and the Journalists’ Union also issued a statement against the government’s decision (full disclosure: this writer is a member of the union’s board).

Despite these various attacks on the media, the most significant threats posed by the Israeli government and military, and especially during the war, are those faced by Palestinians journalists. Figures for the number of Palestinian journalists in Gaza killed by Israeli attacks since October 7 range from 100 (according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists) to more than 130 (according to the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate). Four Israeli journalists were killed in the October 7 attacks.

The heightened government interference in Israeli media does not absolve the mainstream press of its failure to report on the army’s campaign of destruction in Gaza. The military censor does not prevent Israeli publications from describing the war’s consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, or from featuring the work of Palestinian reporters inside the Strip. The choice to deny the Israeli public the images, voices, and stories of hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, orphans, wounded, homeless, and starving people is one that Israeli journalists make themselves.

This article was previously published by +972 here.