A memorial for the man who told the world about the Babyn Yar massacre

Anatoly Kuznetsov is the author of Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel. His memoir is a masterpiece of Ukrainian literature and a testament to the 30,000 Jews massacred at Babyn Yar (the Ukrainian spelling), Kyiv in September 1941. Today it would probably be called “autofiction”, a form of writing where autobiography borrows from the techniques of narrative fiction. However, for Kuznetsov, it is only the form which is novelistic, nothing in the book is fictionalised.

“I am writing it as though I were giving evidence under oath in the very highest court and I am ready to answer for every single word. This book records only the truth – AS IT REALLY HAPPENED.”

The book records the events following the German invasion of Ukraine in 1941 up until Soviet forces recaptured Kyiv at the end of 1943. But it also discusses the Soviet rewriting of history after the end of World War II and the terrible disaster in 1961 that followed the literal burying of the site of the atrocity in sludge and mud.

We only have the full text of this remarkable book because Kuznetsov defected to the UK in 1969 after finally losing faith in the Soviet Union after the invasion of Czechoslovakia the previous year. He smuggled the manuscript out in films hidden in his clothing and this was later translated by the Daily Telegraph journalist David Floyd, who had helped him defect.

Kuznetsov is buried in Highgate Cemetery, two plots up from actor Sir Ralph Richardson and just across from artist Patrick Caulfield and deserves to be just as celebrated. And yet, the grave is unmarked. Pilgrims to the monument to Karl Marx walk past this anonymous plot every day without realising that they are passing the last resting place of one of the most eloquent witnesses to the horrific human cost of totalitarian ideology.

There is now a crowdfunder to raise a headstone for Anatoly Kuznetsov, which has already received wide support.

Luke Harding, the Guardian foreign correspondent and author of several books on Russia recently described Kuznetsov’s book as “a brilliant documentary novel”… “a vivid, terrible and authentic account”.

Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel is presently only available in English in an old American edition from 1970, but it is surely only a matter of time before an enterprising publisher does this great book justice.

There is a fascinating piece in the Index on Censorship archive on Kuznetsov from 1981, two years after the writer died in London. The article, written by film critic Jeanne Vronskaya, discusses two films that were adapted from Kuznetsov short stories in the 1960s: We Two Men and Dawn Meeting. Each, in very different ways, was destroyed by the Soviet censor.

The first was a slice of 1960s neo-realism about a drunken driver who reassesses his life after an encounter with an orphan. The film showed gritty scenes of rural life and included real country people as extras. The film initially avoided the attention of the authorities and was due to be celebrated at a gala event during the 1963 Moscow film festival. But on the day of the screening the film was pulled.

Kuznetsov characterised the attitude of the Communist Party to the film in his interview for Index: “How can we represent the USSR with a picture that shows women dressed in terrible headscarves, snotty-nosed children, rough roads, privately owned geese, illegal private work, and without so much as a mention of the leading role of the Party?”

The film was shelved and a more suitable example of Soviet film making shown in its place. (By way of a sidenote, Fellini’s 8 1/2 won the gold medal at the festival, although the great Italian director’s masterpiece was never distributed in the Soviet Union).

The second attempt at adapting a Kuznetsov story was even more of a fiasco. Dawn Meeting was the story of a milkmaid struggling to survive in the collective farm era. When the censor saw the film, cuts were demanded to make the film more upbeat and patriotic. When Kuznetsov saw the final result he was horrified: “I sat there watching a film that was completely strange to me: about the raising of the standard of living in a progressive, prosperous collective farm, first class houses, excellent clothes, collective farm songs from Moscow Radio’s record library, fields heavy with wheat, and happily smiling collective farmers all over the place.” In a final twist, Dawn Meeting was on billboards all over Moscow when Kuznetsov left for the UK in 1969.

If these short stories are half as good as Kuznetsov’s masterpiece, Babi Yar, then they also deserve a wider readership. But it is his memoir that will act as his testament.

“I wonder if we will ever understand that the most precious thing in this world is a man’s life and his freedom? Or is there still more barbarism ahead?” Kuznetsov wrote those words in 1969. He did not need to answer his own question.

Cancel Putin, not culture

In the dark times

Will there be singing?

Yes, there will be singing

About the dark times.

Bertolt Brecht, motto to Svendborg Poems 1939

For someone who has by now lived most of my adult life in the West but grew up in Belarus – a country that borders both Ukraine and Russia – these have certainly been dark and turbulent times.

The horror of what people in Ukraine are going through is heart-breaking. It is also confusing if my own country of birth is viewed as an aggressor or a victim.

Should people who have bravely protested in hundreds of thousands in 2020 and paid a very high price for it be now equated to the regime that rules them? Does Belarus, the country and the people, mean Lukashenka? What about Russia? The support for Putin is undoubtedly bigger there. But does Russia and Russian culture mean Putin?

Having always been a passionate advocate of freedom of expression under the most trying of conditions, what to make now of the blanket censorship of Russian and Belarusian artists not in Russia and Belarus… but in the West?

When the horror of the invasion of 24 February sank in, the Western cultural scene was immediately rocked by a succession of cancellations and calls for boycotts. Some of them were easier to understand and justify than others.

Opera singer Anna Netrebko and conductor Valery Gergiev have been tied to Putin’s regime and identified as representatives of his soft power: association with them became too toxic for Western cultural institutions. Recently, the evidence of oligarchic wealth accumulated by Gergiev due to his political connections has also come to light. This made any defence of him even more difficult

Art in some ways has always been held hostage. The authoritarian Soviet regime used the prestige of the Bolshoi and the power of Russian culture as soft power.

One is reminded of a powerful 1968 performance by cellist Mstislav Rostropovich at the BBC Proms in London where he performed – intitally to the calls of protest and with tears streaming down his face – a tortured and impassionate piece of music by a Czech composer Antonin Dvorak on the day Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

His wife, the opera singer Galina Vishnevskaya, recalled the event in her autobiography:

“In the hall, six thousand people greeted the appearance of Soviet artists with long unceasing cries, stomping, whistling, preventing the concert from starting. Some shouted: ‘Soviet fascists, get out!’ Others: ‘Shut up, the artists are not to blame!’

“Slava (his nickname) stood there completely pale, absorbing the shame for his criminal government, and I, closing my eyes and not daring to raise my head, huddled in the far corner of the viewing box. But then, finally, the hall fell silent. Dvořák’s music poured over the people like a requiem, and Rostropovich, shedding tears, spoke through his cello.

“The hall froze, listening to the confession of the great artist, who at that moment, together with Dvořák merged with the very soul of the Czech people, suffering with him and with them asking his forgiveness and praying for them.

“As soon as the last note played, I rushed backstage to Slava. Pale, with trembling lips, having not yet recovered from his experience on stage, with eyes full of tears, he grabbed my arm and dragged me to the exit:

“‘Let’s go to the hotel, I can’t see anyone.’

“We went out into the street – the demonstrators were shouting there, waiting for the musicians of the orchestra to express their indignation to them.

“Seeing the two of us, they suddenly fell silent and parted in front of us. In the ensuing silence, not looking at anyone, feeling like criminals, we quickly walked to the car waiting for us and, returning to the hotel, we could finally give vent to our despair.

“But what could we do? We did the only thing that was in our power – got drunk.”

What then should the answer to this moral dilemma be? Should musicians and artists be allowed to perform only once they have stated their opposition to their government?

And is it then morally justifiable from the point of view of Western democracies to put someone living under completely different conditions in that position? To demand dissent from someone who might not be in the position to speak freely?

The German music critic Jan Brachmann gives the example of Dmitri Shostakovich, who, in 1949, appeared at a Soviet-backed peace conference in New York, having been pressured by Stalin into attending.

The émigré Russian composer Nicolas Nabokov publicly interrogated Shostakovich about Soviet denunciations of modernist music, even though he knew that his colleague could not speak his mind. Shostakovich muttered, barely audible: “I fully agree with the statements made in Pravda.”

It is unclear what exactly had been gained from that exercise. But Gurgiev aside and any moral clarity there notwithstanding, there have been other, much less clear-cut cases recently.

Sergei Loznitsa, one of Ukraine’s most prolific filmmakers, who has explored the Maidan uprising, the Donbass war, Stalin’s personality cult and the tragedy behind the Babyn Yar massacre, has recently been expelled from the Ukrainian Film Academy for speaking out against blanket boycott of Russian filmmakers.

His opposition is based on the fact that people should be judged by their actions not their passports. It is hard to disagree. People can still love their country and feel deeply ashamed of their government’s actions.

Kirill Serebrennikov, a Russian dissenting artist of great talent, is currently also in the line of fire.

Serebrennikov, who had his homoerotic production, Nureyev, taken off stage at Bolshoi in 2017, was placed under house arrest accused of embezzling theatre funds – a charge widely seen as being politically motivated. He was not allowed to attend a premiere of his production of Cosi Fan Tutte at Zurich Opera nor to the Cannes premiere of his hugely acclaimed ode to rock ‘n’ roll and dissent in 1980s Leningrad, Leto.

Recently Bolshoi has once again cancelled a scheduled production of Nureyev, this time as a retaliation for him speaking up against the war. Serebrennikov told France 24 in an interview last month that “it’s quite obvious that Russia started the war”, and that it was breaking his heart.

“It’s war, it’s killing people, it’s the worst thing (that) ever might happen with civilisation, with mankind… It’s a humanitarian catastrophe, it’s rivers of blood,” he said.

And yet the Ukrainian State Film Agency opposed Serebrennikov’s inclusion in Cannes Film Festival and the premiere of his new film on the grounds that he is a Russian filmmaker, and it was unacceptable in times of war. While this reaction is humanly understandable and can even be seen by some as a moral decision, we need to ask ourselves who ultimately benefits from silencing, cancelling, de-platforming and similar methods? It is never a viewer, a reader or any ordinary person.

The power of art is in our shared humanity and not in division. Art and its healing power is what gets us through the hard and dark times. We need to show solidarity with people in Ukraine and Ukrainian artists, shine a spotlight on their experiences and prioritise their voices, as well as support those who struggle under authoritarianism in their own countries. This is a task for any functioning democracy.

Having started by quoting Bertolt Brecht, another quotation, this time by the Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn comes to mind: “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart – and through all human hearts.”

This article appears in the forthcoming summer 2022 edition of Index on Censorship. Get ahead of the game and take out a subscription with a 30% discount from Exact Editions using the promo code Battle4Ukraine.

For another view, read Marina Pesenti’s article where she argues that promoting Russian culture risks furthering Putin’s agenda.

Dissidents, spies and the lies that came in from the cold

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

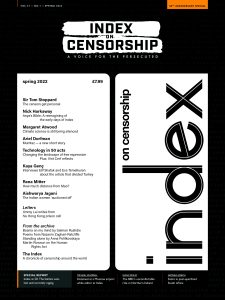

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.