2 Jan 2019 | Global Journalist, Media Freedom, News and features, Russia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”104433″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]A decade ago, Russian journalist Yulia Latynina thought dissidents who compared President Vladimir Putin’s rule to the Soviet times were ridiculous.

“Five to 10 years ago, I would never fear for my life and I would just laugh at people who would compare the situation with the Soviet” era, she says.

Latynina has long hosted a popular talk show on the independent broadcaster Radio Echo Moscow and is a columnist for Novaya Gazeta, a newspaper critical of Putin. Yet in 2008, she turned to Russia’s security service, the FSB, when she felt threatened for her critical views on Russia’s war with neighboring Georgia over the breakaway Caucasus regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. At that time, the state was still willing to protect a Russian journalist, even a critic.

However since Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, things have changed, says Latynina, in an interview with Global Journalist. Attacks against journalists, opposition politicians and activists have been outsourced to people close to the Kremlin, such as Putin associate Yevgeny Prigozhin, she adds. The state will no longer shields its critics.

“The red line is crossed,” she says, in an interview with Global Journalist. “Now it’s quite different. There’s obviously no way I’m going to be protected.”

Indeed, Latynina is no longer laughing about security threats. In 2016, as she was walking in central Moscow, a man in a motorcycle helmet threw a bucket of faeces on her. In July 2017, someone sprayed a noxious chemical all around the house she shared with her elderly parents, sickening two children who lived next door. In September 2017, her parked car was set on fire. To date, their have been no prosecutions in any of the incidents.

Given the frequency with which Putin’s opponents have turned up dead and Russia’s continuing pressure on independent journalists, the attacks were hard to ignore. Shortly after her car was torched, Latynina and her parents fled the country. They’re now living in a different European country, which Latynina won’t disclose out of fear for her safety.

Yet even from abroad, she continues to write for Novaya Gazeta and host the Radio Echo Moscow program “Access Code.” Latynina, who has also written more than 20 books, spoke with Global Journalist’s Shirley Tay about the Kremlin’s outsourcing of political violence and the climate for free expression in Russia. Below, an edited version of their interview.

Global Journalist: A number of journalists critical of Russia have been attacked in recent years. What do you think President Putin’s role is in this?

Latynina: Instead of exercising direct censorship, Mr. Putin is farming out violence to various groups around him. One of the most famous examples is of course the Kremlin “cook,” [Yevgeny] Prigozhin. Novaya Gazeta is writing a lot about him.

Mr. Prigozhin is suspected of organizing numerous attacks on journalists and activists. We have reasons to believe that Mr. Prigozhin very early on took an interest in Novaya Gazeta. He specifically inserted a spy in Novaya Gazeta [who] conducted several operations against its journalists.

GJ: How does this create problems for the Russian state?

Latynina: Obviously there are people behind whom Putin is hiding. So there’s always the idea of plausible deniability.

At the same time, when you’re losing control of violence, what does the modern state do? It has a monopoly over violence. Mr. Putin, he has lost that monopoly on purpose and only to people who are friendly to him. But when you lose the monopoly of violence, this also means you are losing any means to control it.

Despite the fact that I know lots of people behind the government think highly of me…obviously nobody’s going to say no to the people who would like to attack [me]. So that’s the biggest problem.

GJ: You’ve said things have gotten worse over the years. In what way?

Latynina: Russia was a very free country back in the 1990s. It was still not that bad in the beginning of the 21st century. Five to 10 years ago, I would never fear for my life and I would just laugh at people who would compare the situation with the Soviet [era].

I can mention a very funny story that happened to me back in 2008 after the Russia-Georgia war. I was one of the few [Russian] journalists, who from the beginning, was saying that this war is 100 percent an aggression from Russia against Georgia, and it was carried out in a very surreptitious way, just like later with the Ukraine.

I traveled to [the breakaway Georgian territory of] South Ossetia. As far as I surmise the [pro-Russia] South Ossetian authorities didn’t like what I wrote. People were following me. I was thinking they were probably some pro-Kremlin activists. I was so surprised and frightened to see that these are people from the Caucasus. I managed to take a photo of their car – it was without number plates.

I went to Alexei Venediktov, the head of our radio station. I showed him the photo. He talked to Alexander Bortnikov, who was the head of the FSB [Federal Security Service]. I think Mr. Bortnikov didn’t like the idea of Russian journalists being killed by [people] who were definitely not Russian and who were not authorized to carry out this killing.

They gave me protection for six months. And they caught the guys. It was hard because as I said there were no number plates. They never charged them with anything resembling an attack on me, and it turned out they were hardened criminals.

…[But] even eight years ago, despite the fact that the situation in Russia was already very bad and I was one of the most outspoken critics of the Russia-Georgian war, the FSB were definitely unhappy with the idea of somebody killing or at least maiming Yulia Latynina. They were probably thinking that if a Russian journalist is going to be killed, it should be done by the FSB and not by somebody from the outside. I wholeheartedly agree with them on this.

So this was just eight years ago when I could still apply for state protection. After [the 2014 war in] Ukraine, I think this was the limit. The red line is crossed. Now it’s quite different. There’s obviously no way I’m going to be protected.

GJ: Was there a particular article you wrote that sparked the most recent attacks?

Latynina: No, it was just a series of attacks. In the summer of 2016, they covered me in poo. It was actually done very expertly. This is why we immediately realized in Novaya Gazeta who is responsible, but I cannot openly state who is responsible, I have no proof.

The people who did this were following my car, and probably for some time, because I like to walk and my car was parked like two or three kilometers from the radio station.

After they did it, I started running after one of them. He crossed the street and jumped on [the back] of a motorcycle and drove off. The police, in the beginning, they started investigating. They found the motorcycle in question through [surveillance] cameras. They drove to a place where there are no cameras and a lot of warehouses and [the motorcycle] never came out. What came out instead was a small truck with stolen number plates. So obviously there was a very high degree of planning.

This didn’t actually frighten me because obviously if somebody wants to kill you, he doesn’t cover you in poo. So I continued to say what I’m saying.

GJ: What happened next?

Latynina: What happened the next summer [in 2017] when me and my parents are both living in our house, there’s another attack. This one is a very funny one because it’s done with a foul-smelling gas. I couldn’t believe that this is really something directed against us because it seems so funny. It later turned out that the gas, when we analyzed it, it was what you would call a non-lethal military grade substance–very rarely used and very hard to obtain.

When I realized it was done on purpose, I surmised it’s not dangerous because obviously if it’s dangerous it won’t smell so bad. After this my mother had lung problems – it’s a house that’s split in half, we have neighbors – so eight people were affected, two of them children, four of them seniors. This was a very unhappy experience. They put it in my car [too] and it was completely unusable after this because it smelled like a skunk and nothing could be done about it.

A month after this, the car was torched. I believe the only reason it was torched was because probably they were listening to our conversations in Novaya Gazeta and they realized that we were analyzing the substance and they didn’t want it to be analyzed.

The big problem was that I was on a lecture tour outside of Russia, so my parents were home. They torched the car and the problem is that we have a wooden house. My [79-year-old] father ran out, and the car is very close to the house. So he started putting the fire out, and it could have exploded, burning the house.

I guess this was the last straw. This was probably the idea, to drive me out of the country. These incidents came right after I spoke a lot about Mr. Prigozhin and how he got a license to extract oil in those parts of Syria liberated by his [private security company] Wagner.

GJ: You’ve continued your work for Novaya Gazeta and Radio Echo Moscow even while living abroad. Russia is thought to have killed people overseas in the past, including former spy Sergei Skripal in England. Do you think journalists should continue reporting if their life is in danger?

Latynina: First of all, I hope my life is not really in danger, I’m pretty sure a lot has to change in Russia before I become a target of a state-sponsored attack. Trying to kill Skripal and his daughter was a very dirty thing to do, but there’s a big difference between killing an agent who was spying for another country and trying to kill a journalist.

I think Russia has not yet crossed this threshold. Unfortunately, it seems that maybe some people who are private operators did cross the threshold.

I’m constantly waiting for the consequences. I’m not just a journalist, I’m a writer. I want to finish my books on Christianity and I want to finish a couple of novels. So if I really had to choose between my life and reporting, I’m not sure reporting would mean that much to me.

But I hate lies. I hate lies whenever I see them and I just can’t stand lies. So whenever I see a lie, I call it a lie. I cannot make a compromise. My ratings are high because people like what I say. If I start going soft and if I started going all squishy and I just put my head under my wing and slept, people just wouldn’t listen to me. So you have to choose. The only thing that’s changed is that I’m living a much safer and much more relaxed life.

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/_t8aotBf7q8″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Sep 2018 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Russia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102893″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

A country with the largest territory in the world and a turbulent modern history, Russia is home to one of the most difficult media landscapes and censorship has been tightening its grip with new-found strength.

Free media was virtually non-existent during the decades of Soviet rule. It wasn’t until 1991 that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev signed a decree allowing the first independent media outlets to emerge. This was also the year the Soviet Union ceased to be, and Russia was born in its stead. The constitution of Russia, adopted in 1993, guaranteed, among other rights and freedoms, the freedom of speech.

In 2018 it is still the same country with the same constitution, but the initial euphoria for freedom ended abruptly in 2003 after the shake-up of the television channel NTV. From its foundation in 1993 through the early 2000s, NTV was the largest private broadcaster in Russia and a stronghold of free speech, which didn’t suit Vladimir Putin, who first became president in 2000. Witty, free-spoken hosts openly criticised the government, reported on its failures and produced sharp political satire. The undermining of the channel began in 1999 with governmental lawsuits, and the final blow was dealt soon after the tragic events around Nord Ost, the three-day theatre siege in 2002, also known as the Dubrovka terror attack. Putin’s displeasure with NTV’s honest coverage and investigation into the death of 129 hostages, who inhaled an unidentified state-administered gas, resulted in the firing of the network’s CEO Boris Jordan. Soon after, the channel ceased to exist only to be reborn as a state-controlled media outlet with the same name.

Today, mass media in Russia is quite a different scene. The government sets the tone for many things, including the attitude towards journalists. Who are the good guys and who are the bad guys? Which news events should be covered in state media and which are too upsetting to show to the country?

State-owned and state-friendly TV channels like Channel 1 and Rossiya are known for meticulously filtering the inflow of news and dropping the themes and subjects that may throw shadow on the government. The few independent outlets left standing, like Ekho Moskvy, Novaya Gazeta and Dozhd TV, have to endure harassment from power structures and take part in legal battles against governmental institutions and businesses willing to censor them.

Recent additions to Russian legislation make it easier to prosecute media outlets for their reporting. Financial struggle is also real for many Russian media, which are being purchased and reshaped according to the tastes of the new owners, who often happen to have close ties to the Kremlin. That’s what happened to RBC newspaper and TV channel, among others.

Self-censorship is prevalent in newsrooms as well.

The number of threats and acts of violence against journalists has increased three-fold within the last two years, reported Natalia Kostenko, the head of the ONF Centre for Legal Support of Journalists, at a conference in March 2018. Kostenko cited restriction of access, verbal threats, physical violence, damage to personal belongings and lawsuits as the most common misdemeanours against media workers.

However, media freedom is not the only concern in today’s Russia. The political climate has changed drastically over the last few years: the country has seen a surge of nationalism, xenophobia and religious fervour, and the revival of Soviet methods of dealing with “thought criminals”. Under recently passed legislation, a person can be imprisoned for a social media like or repost if anyone considers it to be hateful or extremist. The economic stagnation and financial crisis, which began in 2014 as the result of sanctions against Russia’s actions in Crimea and Donbass, has been an important factor in all of this and contributed to a new wave of emigration, or “brain drain”, that has hit the country. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102871″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Journalists are emigrating from the country for the same reasons as other groups. Some leave to pursue better career opportunities at foreign news outlets. Some follow their families or marry abroad. Some simply want a safer, more open environment for themselves and their children.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102872″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Veteran TV host Tatiana Lazareva found herself unable to find any work on Russian television after she and her husband Mikhail Shatz took part in covering opposition leader Alexey Navalny‘s protests in 2012. This got them blacklisted on most Russian TV channels. “I don’t have a profession anymore,” Lazareva told Dozhd TV in an interview last year. “As I see it now, they wanted to take not only television away from us, but any chance to make money, wanted us, like, to crawl on our knees and beg.”

She moved to Spain, where she and her family had been spending their holidays for 15 years, to raise her youngest daughter. Lazareva continues her charity work in Russia and heads a motivational programme for people over 50, but the door to journalism in her country remains closed.

Lazareva’s example is not unique, and many young journalists now prefer to either start their careers abroad or change professions. For some journalists, leaving Russia is the only possible choice.

Vocal and straightforward, Karina Orlova had been a journalist at Ekho Moskvy radio for over a year when the attack on the French magazine Charlie Hebdo took place. A few days after the massacre, she hosted a show with Maxim Shevchenko, a right-wing journalist and then-member of the Russian Presidential Council on Human Rights. Orlova asked Shevchenko to comment on the threatening statement made by Chechen Republic leader Ramzan Kadyrov in response to exiled businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s suggestion that every media outlet should republish Charlie Hebdo’s controversial Prophet Mohammed caricatures as an act of solidarity. Kadyrov called Khodorkovsky “the enemy of all Muslims” and his “personal enemy”, and said he hoped someone “would make the fugitive answer” for his words. Shevchenko kept defending Kadyrov’s point of view, while Orlova attempted to get Shevchenko to acknowledge the severity of the threats and report them to the council. For this, she too became a target. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102873″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Orlova’s mother discovered that threats were being made under the journalist’s profile on a website for local journalists. Orlova then began receiving threats through her Facebook account. She could tell there was something different about these threats – they weren’t like the usual outbursts she encountered while on air. The men, residents of Chechnya and Ingushetia, didn’t try to hide their identity. They called Orlova “the enemy of Islam” and promised to kill her in many different ways. At the same time, Kadyrov directed threats to Ekho’s staff chief editor Alexey Venediktov.

In haste, Orlova packed her things and boarded a flight to the United States, which she believed to be the safest place for her. It took her some time to feel comfortable in the new environment and polish her English skills. She still contributes to Ekho, but her main job is with an American political magazine.

“Return to Russia? I can’t, I don’t want to and I won’t. Russia is a dangerous country where the raging of the power structures got even more out of hand in the last three years,” Orlova says. “There are no independent courts, the police only chases the “enemies of the state” and robs local businesses.”

Despite being away from Russia for three years, Orlova’s name hasn’t been forgotten. “In January 2018 director Nikita Mikhalkov filmed an episode of his TV show, Besogon (“Exorcist” in Russian), about me. He called me Goebbels and a fascist for an old article in which I suggested that Russia needed a lustration, and all people who worked in the Soviet system should be excluded from the government. Last time Besogon covered an Ekho journalist, Tanya Felgengauer was brutally attacked,” Orlova said.

Echo Moskvy’s Tatiana Felgengauer, a host and one of the editor-in-chief’s deputies, was stabbed several times in the neck in the station’s office. (Photo: Facebook)

Ekho host Tatiana Felgengauer was stabbed in the throat in October 2017 at the station’s headquarters. The attacker pepper-sprayed a guard and went for Felgengauer once he reached the office. He was deemed to be a paranoid schizophrenic and sentenced to compulsory medical treatment by the court.

Yulia Latynina (Twitter)

As one of the most noticeable and outspoken radio hosts in Moscow, Felgengauer was criticised by Russian state outlets more than once. Just a week before the attack she was called a “traitor of the motherland” on state television for attending a conference sponsored by foreign human rights organisations. She survived thanks to quick medical attention and has since fully recovered and returned to work. Nevertheless, it was a very close call.

Soon after the attack Ksenia Larina, another Ekho journalist, began receiving death threats. Not taking any chances, she promptly left the country for Europe.

Yulia Latynina hosted her own show at Ekho while also contributing to the newspaper Novaya Gazeta. The sharp-tongued novelist and journalist has been an object of criticism for many years, but the final straw for her came in September 2018 when her car was burned out right outside her country house, which had previously been sprayed with a dangerous military-grade chemical. Latynina now spends her time between different countries and has no plans to return to Russia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_column_text]

No other Russian outlet has seen more of their journalists threatened, attacked and murdered over the years than Novaya Gazeta. One of the last bastions of Russian free press standing, the newsroom works under extreme pressure, carrying on in the same line of work as their fallen colleagues, who paid with their lives to get the truth out.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102877″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2000, Igor Domnikov, reported on business corruption in Moscow. Beaten to death outside his apartment by multiple men wielding hammers. Some of the murderers were arrested and sentenced in 2007, while the mastermind of the crime was let go.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102880″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2003, Yury Schekochikhin, investigative journalist. Died of a mysterious 16-day illness, possibly poison. Real cause of death never determined, independent investigation banned, case closed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”85407″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2006, Anna Politkovskaya, most famous for reporting about the Second Chechen War. First poisoned in 2004, recovered; then shot dead in her apartment building right on Vladimir Putin’s birthday. Murderers found and jailed, mastermind never found, investigation closed. Politkovskaya won an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for her courageous journalism.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102879″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2009, lawyer Stanislav Markelov and freelance reporter Anastasia Baburova. Both shot in the head on a Moscow side street in broad daylight. Both the killers and the mastermind found and jailed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102878″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2009, Natalia Estemirova, human rights activist and journalist in Chechnya. Abducted near her home and found dead with bullet wounds in a woodland miles away. The killer was identified by the officials and allegedly killed in ambush. The newspaper staff is skeptical of this version, as the man’s DNA samples didn’t match the ones found on the crime scene.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

It would only be fair to say that Novaya Gazeta management knows pretty well when a threat is real. So instead of waiting for governmental protection, they take their own precautions. Here are just some of the recent stories of those who left the country before it was too late, related by the paper’s former chief editor Dmitry Muratov:

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102890″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Sergey Zolovkin used to be a police officer who solved many crimes, co-founded Sochi newspaper and was a Novaya Gazeta author. He was threatened many times, his car sabotaged, relatives beaten up, an attempt on his life made in 2002 – the would-be killer was caught on the spot as Zolovkin was armed; he moved to Germany soon after.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102891″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Maynat Abdulaeva (Kurbanova) was reporting from Grozny, Chechnya, for years, until she and her family started receiving death threats. She has been living in Germany under PEN program Writers in Exile since 2004.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102889″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Evgeniy Titov left in 2016. He reported on human rights violations in Krasnodar and corruption around Sochi 2014 Olympics, was threatened by the police and private individuals, and requested asylum in Lithuania.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102888″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Elena Milashina co-authored the 2017 world-famous investigation about hundreds of gay men kidnapped, tortured and killed in Chechnya in a covert attempt to “purge” the region. Having been previously attacked and beaten up in 2006 and 2012, she fled Russia following death threats from Chechen officials and Muslim preachers, but continued to cover the region.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102885″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Ali Feruz (pen name) reported on hate crimes, LGBTQ and migrant worker’s rights. He was born in Uzbekistan, though his mother was Russian. He escaped from the country after being detained and tortured by the Uzbek National Security Service, who wanted his cooperation. Feruz moved to Russia and tried to obtain a Russian citizenship on jus sanguinis principle. His initial appeal was turned down, but a new case looked promising. He was suddenly arrested in August 2017 and sentenced to deportation to Uzbekistan. In the following three and a half months Feruz was abused and tortured in detention – and no one got punished for it. He was rescued and granted asylum by the German government, and will never be able to return to Russia. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102886″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Elena Kostychenko was one of Novaya Gazeta’s most fearless and fierce reporters, having covered complex stories all over Russia. She is also a feminist and LGBTQ activist, and in 2011 was left with a concussion after being attacked at a pride parade in Moscow. In 2016 Kostychenko was brutally beaten in Beslan while covering a protest of the mothers whose children died in the 2004 school terror attack. She is still recovering from psychological aftershocks, abroad.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

528 press freedom violations in Russia verified by Mapping Media Freedom as of 27/9/2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGMTAwJTJGbWFwJTIyJTIwZnJhbWVib3JkZXIlM0QlMjIwJTIyJTIwYWxsb3dmdWxsc2NyZWVuJTNFJTNDJTJGaWZyYW1lJTNF[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538042702741-bc2cc3fd-837d-0″ taxonomies=”7349, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 May 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Updated statement: High profile Russian journalist and Kremlin critic Arkady Babchenko staged his own “murder”, it was revealed in a press conference where the journalist appeared on Wednesday 30 May. Earlier news reports have said he was shot and killed in Kiev, Ukraine, at his home, where he lived with his wife. However, that has since been revealed to be untrue.

Babchenko claimed it was necessary to do this in order to catch people who were trying to kill him.

Babchenko left Russia in February 2017, writing that it was “a country I no longer feel safe in”. Babchenko, a former war correspondent for Novaya Gazeta, was known for his fierce criticism of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, its support for separatists in eastern Ukraine and its military intervention in Syria.

Index calls on the Ukrainian police to continue their investigations into the 2016 murder of journalist Pavlo Sheremet, which has yet to be solved.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1527698401910-293e4fff-01bc-10″ taxonomies=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Mar 2018

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521806157541{margin-top: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_web-cover.jpg?id=98589) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521805928920{margin-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

The case of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who had for years worked to shine a light on corruption among politicians, businessmen and criminals in Malta, highlights the dire need for a free press. Between 2016 and 2017 Caruana Galizia linked the Maltese political elite to the Panama Papers, including the financial affairs of the prime minister, his wife and the leader of the country’s opposition party.

For her work, she paid with her life when a bomb exploded under her car on 16 October. She was not the only journalist to be murdered in Europe in 2017, nor were violations of media freedom confined to any one region.

Mapping Media Freedom has been recording threats to press freedom since 2014, highlighting the need for protection for journalists. The project monitors the media environment in 42 European and neighbouring countries. In 2017 1,089 reports of limitations to press freedom were verified by a network of correspondents, partners and other sources based in Europe, with a majority of violations coming from official or governmental bodies.

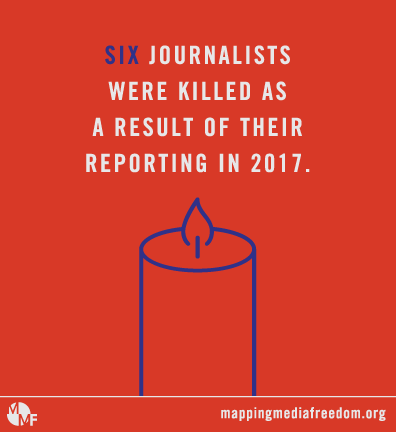

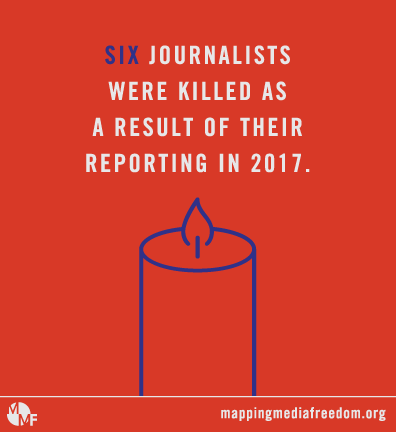

Six journalists were killed during 2017; 178 reports of assault or injury were made; 220 media workers were detained or arrested; 193 reports included criminal charges and lawsuits; there were 367 reports of intimidation, which includes psychological abuse, sexual harassment, trolling/cyberbullying and defamation; in 113 incidents media professionals had their property vandalised or confiscated; there were 178 instances of journalists or sources being blocked; and journalists’ work was altered or censored 68 times.

“While the number of incidents reported to Mapping Media Freedom decreased between 2016 and 2017, this should not be taken as an indication that the work environment for journalists has improved in the countries monitored by the platform,” Hannah Machlin, project manager of Mapping Media Freedom, said. “Media professionals still work under threat of death, assault, prison and harassment, while the law is being abused as a means to silence those who seek to tell the truth.”

ABOUT MAPPING MEDIA FREEDOM

Each report is fact-checked with local sources before becoming publicly available on Mapping Media Freedom. The number of reports per country relates to the number of incidents reported to the map. The data should not be taken as representing absolute numbers. For example, the number of reported incidents of censorship appears low given the number of other types of incidents reported on the map. This could be due to an increase in acts of intimidation and pressure that deter media workers from reporting such cases.

The platform – a joint undertaking with the European Federation of Journalists partially funded by the European Commission – covers 42 countries, including all EU member states, plus Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Turkey, along with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (added in April 2015), and Azerbaijan (added in February 2016). The database uses Ushahidi, an open source software to map and categorise incidents.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Deaths” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Q1: In Russia on 9 March, two unknown individuals approached Nikolai Andrushchenko, an investigative journalist for the weekly newspaper Novyi Petersburg, near his home in St. Petersburg and demanded that he surrender documents and materials from his ongoing investigation into abuses of power by police officers. After the journalist refused, he was physically assaulted by the assailants, who were not apprehended. Andrushchenko refused to file a complaint with the police. A second assault took place a few days later, after which he was found unconscious near his apartment. The journalist never regained consciousness and, following brain surgery, died in hospital as a result of his injuries on 19 April.

On 16 March, in Ulan-Ude, Russia, Yevgeny Khamaganov, the editor-in-chief of Asia-Russia Daily and The Site of the Buryat People died in unexplained circumstances. The cause of death is unclear and no official response has been made. According to local media, Khamaganov was taken to hospital on 10 March because of his diabetes, fell into a coma and died several days later. Some reports cited speculation that he was instead hospitalised after being beaten by unknown assailants. Khamaganov was known for articles critical of the Russian federal government’s policies.

Q2: In Minusinsk, Russia, journalist Dmitri Popkov, editor-in-chief and founder of local newspaper Ton-M, was shot five times and killed on 24 May. His body was found in a sauna in his backyard. Prior to his death, Popkov had told RFE/RL that his newspaper became “an obstacle” for local officials who are now “threatening and intimidating journalists”.

Q3: On 10 August Swedish freelance journalist Kim Wall boarded an experimental submarine in Copenhagen, Denmark, to profile the vessel’s Danish inventor. The following morning, the submarine sank under suspicious circumstances. Peter Madsen, the inventor, told police he had set Wall ashore before the incident. However, between August and October, Wall’s dismembered remains were found washed ashore. Madsen has been charged with the journalist’s murder and with sexual assault.

On 22 September Syrian journalists Orouba Barakat and her daughter Halla Barakat were found dead in their apartment in Istanbul, Turkey. The exact date of the murders is unknown. Orouba Barakat, a journalist, filmmaker and activist, was outspokenly critical of the Syrian regime. Her daughter was a reporter for Alekhbarya TV, news editor for the Orient and a former editor at Turkish state channel TRT World. The pair had received threats from groups associated with the Syrian government. Police reports said they were strangled and then stabbed. The murders are still being investigated by police.

Q4: Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed when the car she was driving exploded in Bidnija, near Mosta. Caruana Galizia had filed a police report 15 days earlier saying she was being threatened. The journalist had conducted a series of high-profile corruption investigations in Malta and was being sued in relation to her work.

One additional media worker was killed in 2017. On 29 April Saeed Karimian, an Iranian television executive, was shot and killed along with his partner in Istanbul, Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Physical assaults and injury” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

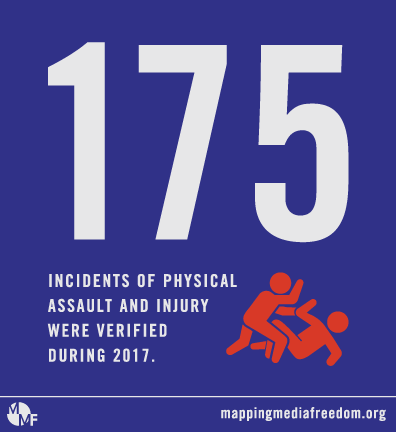

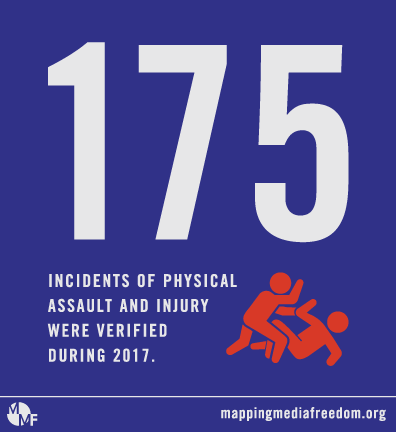

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

On 14 September Taras Khalyava, a local YouTube blogger, was assaulted by three unidentified people near his apartment in Dobropillye, Ukraine. The assailants knocked him to the ground, kicked him and beat him on the head with a steel rod. “I survived because I was wearing a bicycle helmet,” Khalyava told Novosti Donbassa. The blogger has said the attack was related to his work.

On 10 October, Drago Miljus, a Croatian journalist for the news website Index.hr, was pushed by a police officer, who then took his mobile phone and threw it into the sea. Another officer hit the journalist on the head, knocking him to the ground. The incident happened at a beach in Split, where Miljus was covering a story about a man who claimed to have a bomb.

On 23 October, a man broke into Echo Moskvy’s office in the centre of Moscow, Russia, and stabbed programme host Tatiana Felgengauer, who is also one of the editor-in-chief’s deputies, several times in the neck. Felgengauer was hospitalised in a critical condition and underwent several operations. The attacker was sent for psychiatric evaluation.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Arrests/Detainments” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court.

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court.

Mapping Media Freedom verified the arrest or detainment of 65 journalists in Russia throughout 2017. The majority of these took place during anti-corruption protests throughout the country organised by opposition figure Alexei Navalny in March and June.

By the close of 2017, 151 journalists were in prison in Turkey, making the country the largest jailer of journalists in the world. On 20 October police took five journalists working for the Kurdish Jin News and Mesopotamia agencies into custody: Jin News editor Sibel Yükler; Jin News reporters Duygu Erol and Habibe Eren; and Mezopotamya Agency reporters Diren Yurtsever and Selman Güzelyüz. Both agencies were launched in late September by staff from organisations shut down during Turkey’s state of emergency.

While only five media workers were arrested or detained in 2017 in the United Kingdom, one case stands out. On 7 December two Kurdish women and two 17-year-old boys were arrested at dawn by armed police in Alexandra Palace and in Crouch End, London. They were questioned about the sale and distribution of the Kurdish-language Yeni Ozgur Politika. All four were arrested on suspicion of funding terrorism, money laundering and fraud.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Criminal charges/civil lawsuits” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest.

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest.

In Spain, wealthy businessman Alvaro de Marichalar filed legal action against freelance journalist Sabina Urraca in March, demanding she pay €30,000 in damages for an article she wrote after accompanying him on a trip. In July Hermann Tertsch, a columnist for daily newspaper ABC, was ordered by a court in Zamora to pay €12,000 to Javier Iglesias for “unlawfully offending the honour” of his father Manuel. Javier Iglesias is the father of Pablo Iglesias, the leader of the left-wing Podemos party, the third largest party in the Spanish parliament.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Legal measures” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.

In February the UK government proposed extending jail time for journalists who have obtained leaked official documents to up to 14 years. The major overhaul of the Official Secrets Act – to be replaced by an updated Espionage Act – would give courts the power to increase jail terms against journalists receiving such material. Should the law get approval, documents containing “sensitive information” about the economy could fall foul of national security laws for the first time. Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive of Index on Censorship, said: “It is unthinkable that whistleblowers and those to whom they reveal their information should face jail for leaking and receiving information that is in the public interest.”

In November, after the US added several media outlets funded by the Russian state on a list of foreign agents, Russia adopted a new restrictive law against foreign media that allows such journalists and organisations to be recognised as foreign agents, which makes them subject to numerous additional checks and obliges them to mark their content as being produced by a foreign agent.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Job loss” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

In Poland, Michał Fabisiak, a journalist for the public media outlet Polskie Radio, was fired for refusing to reveal the source of information for an article about an alleged internal survey in the Law and Justice (PiS) party, measuring support for potential PiS candidates in municipal elections in 2018.

Eleven days later, Barbara Burdzy, a Polish journalist for the public media outlet TVP Info, was dismissed after she published an article stating that the intelligence service, under the minister of defence Antoni Macierewicz, lied when claiming that deputy minister Jacek Kotas was not involved in property restoration in Warsaw.

On 14 December a documentary critical of Togo’s president was removed from the website of the French cable television channel Canal Plus and two employees of the channel were subsequently dismissed. Faure Gnassingbé, the president of Togo, is a friend of Vincent Bolloré, French businessman and chairman of Canal Plus’ parent company Vivendi. The documentary, entitled Let Go of the Throne, focused on ongoing protests against the country’s president. In November it was aired on Canal Afrique, a decision attributed to an employee who was later fired. François Deplanck, head of channels and content at Canal Plus International was also dismissed.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Intimidation” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

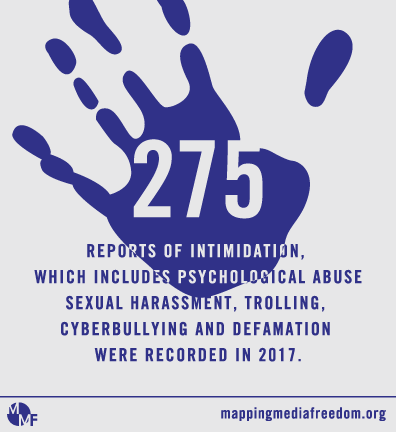

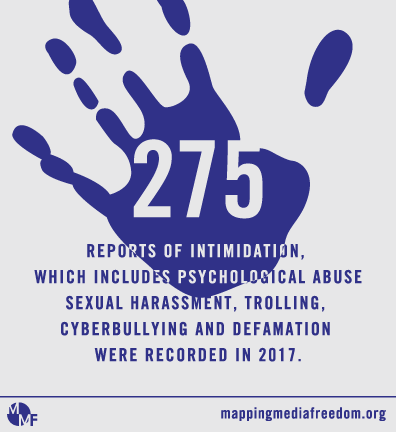

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.

Kuenssberg — the first woman to lead political coverage at the public broadcaster — also reported that she had bolstered her security during the general election in June 2017 after receiving threats over her coverage of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Attacks to property” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.

Supporters of the Italian far-right party Forza Nuova attacked the offices of the left-wing newspaper La Repubblica in Rome on 6 December. The party declared “war” on L’Espresso Group, the newspaper’s publisher, through a Facebook post. During the protest, Forza Nuova supporters threw flares at La Repubblica’s office while carrying a banner reading “Boycott L’Espresso and La Repubblica”. Members of the group read a statement denouncing journalists employed there.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Blocked access” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

Throughout Europe, journalists were blocked from attending events by political parties, including the Labour Party’s annual conference in Brighton, United Kingdom, in September. Sussex police refused to grant Huck Magazine news editor Michael Segalov the security clearance he needed to attend. The journalist had applied for press accreditation three months prior but was informed on 19 September that it had been denied by police on security grounds. “Rather than provide reasons and rationale for our journalistic freedom being curtailed, the police said they would not divulge why they made their call,” Segalov wrote. The journalist has never been arrested, charged or convicted of a crime. Michael Walker, a journalist working for the left-wing Novara Media, was also barred by police from entering the conference.

On 25 October three journalists working for Echo TV in Hungary were banned from entering the country’s parliament. The parliament press office said the journalists had broken official rules multiple times by filming in areas closed to the media.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Work censored or altered” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.

On 4 November the Spanish newspaper El País removed a column from its website that questioned and criticised allegations of sexual harassment in the film industry against the likes of Kevin Spacey, Harvey Weinstein and Roman Polanski.

On 19 December the Malta Independent, a Maltese newspaper and publishing house, announced it would remove some online content relating to a whistleblower at Pilatus Bank due to the threat of a multi-million euro lawsuit from the bank. Pilatus Bank first threatened the independent publishing house in mid-October, with lawsuits in the USA and United Kingdom.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black” style=”dashed”][vc_column_text]

CASE STUDIES

2018 WATCH LIST

Index on Censorship is especially disturbed by the five countries on the map with over 60 violations in 2017. These are:

Russia (197)

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny.

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny.

On 20 December photographers Andrey Zolotov and Denis Bochkarev, along with Maria Alyokhina, a member of punk collective Pussy Riot, were detained during a protest at the entrance of the FSB, the Russian federal security service. All three were taken to the nearest police station, where Alyokhina and Bochkaryov spent the night ahead of an administrative hearing.

Often referred to as the only independent radio station in Russia, Echo Moskvy was subjected to significant pressure and harassment throughout 2017, with Mapping Media Freedom verifying 15 reports against the station including one radio host stabbed, two journalists fleeing the country after threats, several detained and an American company forced to withdraw funding from the station.

Turkey

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police.

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police.

In November, Turkish journalists Ahmet Altan and Mehmet Altan’s defence attorneys were forced to leave the courtroom as their clients stood trial, accused of taking part in Turkey’s failed 2016 coup. Both brothers are prominent Turkish journalists, known for their critical reporting on president Erdogan’s regime. Without lawyers present, the court then ruled that the Altan brothers — along with four other journalists — would remain in pretrial detention. On 16 February 2018 they were sentenced to aggravated life sentences.

Belarus

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests.

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests.

Throughout the year, 69 fines were administered to journalists for violating Article 22.9 of Belarus’ Code of Administrative Offences on the illegal production and/or distribution of media content.

Ukraine

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine.

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine.

Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko signed a National Security and Defence Council decree in May that banned a number of Russian social media sites such as VKontakte and Odnoklassniki, along with the search engine Yandex and email service Mail.ru.

“The lack of safety for journalists in Ukraine, whether direct attacks or obstruction, remains a problem, and the level of response by the authorities is telling because too often the perpetrators go unpunished,” Vitalii Atanasov, Mapping Media Freedom correspondent for Ukraine, said. “The murder of prominent journalist Pavel Sheremet in July 2016 has not yet been properly investigated, while media workers continue to face pressure from the authorities, politicians and other influential actors. It is important to emphasise to that while the Mapping Media Freedom reflects the most disturbing and characteristic cases, it does not claim to be complete.”

Spain

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence.

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence.

On the day of the referendum Mapping Media Freedom recorded five separate violations of media freedom. Journalists were among the many victims of violence by heavy-handed police deployed the Spanish government, who declared the referendum to be illegal. Xabi Barrena, a journalist for the newspaper El Periódico, was assaulted by Spanish national police while reporting on voters being evicted from a polling station in Barcelona. He was struck with a baton, knocked to the ground and kicked by police.

In the days following the referendum, media violations were widespread during the protests that swept parts of the country. On 2 October, for example, Ana Cuesta and José Yelámo, reporters for television La Sexta, were surrounded by protesters who chanted “Spanish press manipulators” and “assassins” during live coverage.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

TRENDS

Threats from the far-right

The far right has a record of violating freedom of the press throughout Europe, with 24 media violations across 13 countries involving far-right groups or activists in 2017.

Twelve attempts were made by the far-right to intimidate media workers. At the start of December, the Serbian journalist Marija Antic, a television host for the broadcaster N1, received death and rape threats on social media after interviewing a French-Serbian far-right activist. Antic had invited Arnaud Gouillon, who is known for his support for Serbs in Kosovo, to her talk show. During the interview, Antic asked him about his past involvement in the French far-right group Les Identitaires and about his connections with far-right Serbian groups after he attended some of their events. After the interview, Gouillon accused Antic of demonising him. Soon after, Antic received multiple threats on social media.

On six occasions, far-right groups attempted to defame journalists throughout Europe. This was the case on 15 March when Stina Blomgren, a Swedish journalist working for the state broadcaster SVT, was accused by the popular Swedish-Russian far-right blogger Egor Putilov of lying and creating fake reports about the risks Syrian migrants faced when trying to reach Sweden. Putilov claimed to have visited Egypt and uncovered inaccuracies in an article published by Blomgren in August.

In 2017 four reports made to Mapping Media Freedom involved violence from the far right and four involved attacks to property. These ranged from damages to camera equipment to an assault with a metal pipe.

Corruption

Corruption is a major issue in the EU and neighbouring countries, undermining democracy and putting people at risk. Journalists play a key role in uncovering and fighting corruption through their investigations and, as a result, put themselves in danger. In all, 67 cases of media workers facing difficulty in their reporting on corruption were recorded throughout 2017.

On 16 August, for instance, Parim Olluri, editor-in-chief of investigative website Insajderi, was physically assaulted by unknown individuals outside his home in Kosovo’s capital Pristina. Olluri believes the attack was linked to his work. A few days before the assault, Olluri had published an editorial about corruption allegations against former Kosovo Liberation Army commanders, after which he received a torrent of abuse and threats on social media.

On 16 October the Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered when the car she was driving exploded. On 11 March Silvio Debono, owner of real estate investment company DB Group, filed 19 libel cases against her. Caruana Galizia published a number of articles on her blog discussing a business deal between the developer and Malta’s government to take over a tract of public land on which he had planned to build a Hard Rock Hotel and two towers of flats for sale. Caruana Galizia also conducted an investigation allegedly linking prime minister Joseph Muscat and his wife to the Panama Papers scandal.

Harassment of female journalists

Mapping Media Freedom logged 10 cases where women journalists reported they suffered sexual harassment throughout 2017, from politicians, anonymous sources and fellow journalists alike. In February the Swedish newspaper journalist Evelyn Schreiber was subjected to persistent death threats and threats of sexual violence after questioning local police officer a Peter Springare’s assertion that immigrants were responsible for a spike in violent crime in Örebro, Sweden. Within 24 hours of her report, Schreiber received over 200 emails containing threats.

On 7 May Loes Reijmer, a journalist and columnist for the Dutch daily newspaper De Volkskrant, faced abuse after the popular right-wing blog GeenStijl published a photo of her with the text: “Would you do her?” Thousands of readers responded in the comments section, many containing sexual references and rape threats. Reijmer had published several articles critical of GeenStijl, which is owned by Telegraaf Media Group and is one of the top 10 most popular news sites in the Netherlands.

On 30 November, Dzenan Selimbegovic, a deputy secretary general of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, used offensive language to describe Sanele Prašović Gadžo, a journalist for the public broadcaster BHT, and Arijana Saračević-Helać, a journalist for the public broadcaster FTV, in a Facebook post. The comments followed a trailer aired on BHT for Gadžo’s interview with Saračević-Helać on her talk show.

Commercial interference

In 2017 Index on Censorship added the “commercial interference” category to Mapping Media Freedom to monitor actions that use money and/or financial pressure to influence editorial decisions of a media or news outlet. One of the most concerning issues highlighted was the lack of plurality in media ownership in Ireland and the impact this can have on the public’s right to information.

Broadcasting in the country is dominated by just two organisations, RTÉ and Communicorp. Semi-state RTÉ services are the most popular on television and radio, while businessman Denis O’Brien’s Communicorp owns the largest commercial news radio stations – Newstalk and Today FM, among others. There is currently a lack of imperative for reform on the issue of the concentration of media ownership by the Irish government, leaving journalists open to further pressure and self-censorship to suit commercial interests, according to the National Union of Journalists.

Across Europe commercial interference in the media is proving to be a growing problem. On 6 December in Nantes, France, for example, managers of McDonald’s restaurants were asked to remove a page from local newspaper Ouest France that contained an article about litigation between the fast food restaurant chain and two of its workers, who had campaigned for union representation.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Mapping Media Freedom’s annual report highlights issues affecting the state of press freedom throughout Europe in 2017. Index on Censorship urges that the following steps be taken.

-

All journalists, media workers and others arrested for exercising their right to freedom of expression must be immediately and unconditionally released. We make this plea directly to the Turkish government in particular, which has become the largest jailer of journalists not just among the countries monitored by Mapping Media Freedom, but the entire world.

-

Laws designed to impinge on the work of journalists must be reconsidered, whether amended or abolished. This includes defamation laws, hate speech laws and terror and security-related legislation. Lawmakers should also ensure that new or revised laws do not encroach on the work of journalists.

-

Governments must respect the right of journalists to protect confidential information and sources. This is vital, especially in cases involving whistleblowing in the public interest.

-

Harassment and crimes against journalists must be properly investigated and those responsible should be prosecuted to prevent the further proliferation of impunity.

-

Governments should do more to ensure the protection of media workers who are women.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1521129408155{background-color: #d5473c !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protect media freedom”][vc_column_text]

We monitor threats to press freedom, produce an award-winning magazine and publish work by censored writers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521129253575{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_map-standalone.jpg?id=98665) !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.  Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).  A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July  There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017.

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017.  There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).  Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the  There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service.

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service.  There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.  In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a  During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara.