19 Apr 2017 | Awards, Awards Update, Digital Freedom, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

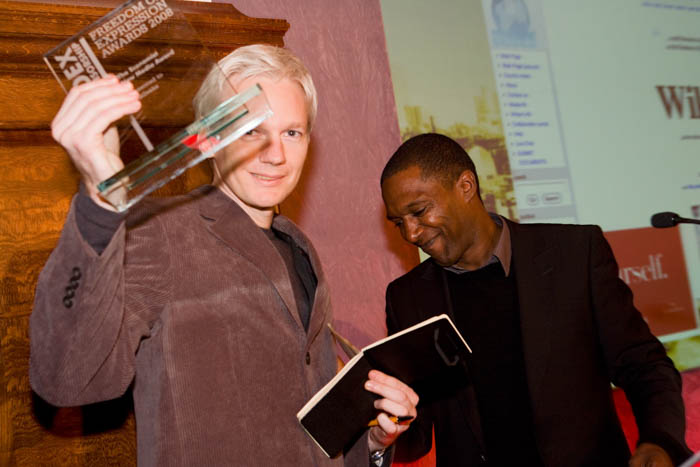

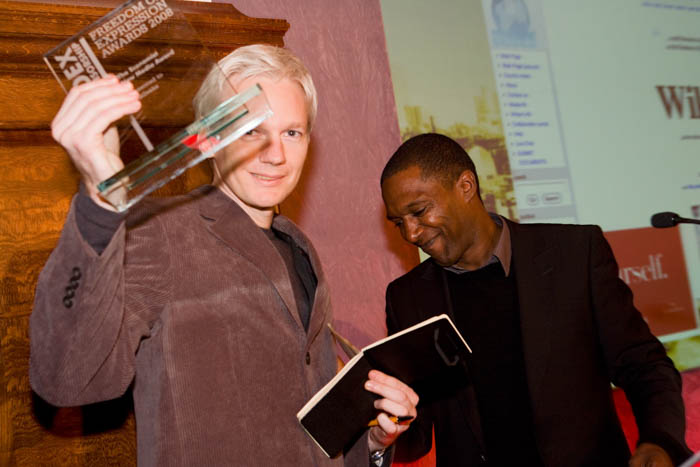

It has been over a decade since WikiLeaks released its cache of leaked documents and a little under a decade since it was awarded The Economist New Media Award at the 2008 Freedom of Expression Awards. In the following years, the non-profit organisation has published a considerable body of documents, holding to account states, corporations and individuals. Such actions would imply that it remains an apolitical organisation, whose mission is to ensure the defence of free speech and vitiation of censorship, although of late some would dispute its primary function. On the day of this year’s Dutch general election, WikiLeaks made separate Tweets with links to all documents referencing either Prime Minister Mark Rutte or right wing populist Geert Wilders.

Their fight for freedom of expression is often amorphous, which is well demonstrated by two publications from 2009. First, the March release of a website blacklist, proposed by Australia’s then communications minister, Stephen Conroy. Although it had been suggested by the Australian Government that the compulsory firewall would obstruct access to child pornography and sites related to terrorism, it was revealed to have included numerous websites which suggested a veiled political agenda. Second, the September release of an internal report on a toxic incident clean-up in the Ivory Coast by the oil trading company, Trafigura. That draft report was released after Trafigura obtained a super-injunction against The Guardian. Comparing the two, it is clear they share a commonality in combating instances of censorship, but beyond that an underlying characteristic in the material released is hard to find.

Where the organisation has had a focused, profound, and some would say not impartial, impact is on American politics. Three particularly notable moments were the 2010 Iraq and Afghanistan ‘War Logs’ and diplomatic cables associated with Chelsea Manning, the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak, and the recent CIA Vault 7 release. It is perhaps the second of these that questions WikiLeaks’ apolitical position; in an interview with ITV, Julian Assange stated that he hoped the leaks would harm Hillary Clinton’s campaign. Certainly, the furore which surrounded Clinton’s use of a private email server in handling sensitive documents and the March 2016 release of her email archive was a boost for the Trump campaign. It remains to be seen whether the Trump administration or affiliated groups will be the subject of a WikiLeaks publication.

Whether one considers WikiLeaks a paragon, a zealot, or Machiavellian, it remains a powerful force against censorship. Although their profile has grown since being awarded The Economist New Media Award, they are still an organisation that appears wholly unconstrained by diplomatic pressures in holding bodies to account, who or whatever the target.

Samuel Rowe is a member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board. He is currently a law conversion student at City, University of London, planning on practicing as a public law barrister with a focus in information law.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”85476″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/awards-2017/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

Seventeen years of celebrating the courage and creativity of some of the world’s greatest journalists, artists, campaigners and digital activists

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492506268361-b3958523-724a-7″ taxonomies=”273, 8935″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Feb 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

To highlight the most pressing concerns for press freedom in Europe in 2017, members Index’s outgoing youth board review the year gone by with some of our Mapping Media Freedom correspondents.

Youth board member Sophia Smith Galer, from the UK, spoke to Ilcho Cvetanoski, Mapping Media Freedom correspondent for Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Macedonia.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

The breaking up of the former Yugoslavia has undoubtedly been a historical burden on Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Cvetanoski describes this legacy as having left “deep scars in every aspect of the people’s lives, including the lives and the work of journalists”. Media workers are still remembered as having once been tools of the state. Nowadays, the opposite is happening; they’re being criticised by political elites as enemies of the state simply for scrutinising politicians’ behaviour.

It’s unsurprising that this has left many journalists in the region politicised, undermining professionalism and trust in the media. Conservative politicians court sympathisers in the media so that they can manipulate the angle and content of stories that are run. The fact that journalist salaries are low and that the economic situation is poor overall further imperils journalistic integrity in the face of bribes.

If the situation remains as it is – with limited and highly controlled sources for financing the media, a poor political culture and low media literacy among citizens – then Cvetanoski holds little hope for the future of press freedom in the region. News consumers aren’t equipped with the literacy levels to distinguish between professional versus sensational journalism, nor are the sources of media funding transparent or appropriate. “In this deadlock democracy, the first victims are the citizens who lack quality information to make decisions.”

Mapping Media Freedom is helping to change this. Making journalists feel less alone and offering a space for them to report threats to press freedom ensures that the hope for a free press throughout Europe is kept alive.

The youth board’s Constantin Eckner, from Germany, spoke with Zoltán Sipos, the MMF correspondent for Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

Index on Censorship’s regional correspondent Zoltán Sipos, who is also the founder and editor of Romania’s investigative outlet Átlátszó Erdély, points out that the Hungarian government and its allies within the country follow a sophisticated plan to neutralise critical media outlets. Several newspapers that struggled financially have been purchased by rich business people or media moguls in recent history. “Just like in regards to any other part of society, prime minister Viktor Orbán seeks for a centralisation of the media industry,” Sipos says.

Yet, instead of simply controlling the media, Orbán and the reigning party Fidesz intend to use established outlets and broadcasters to construct narratives in favour of their agendas. Only a handful of independent outlets remain in Hungary.

In November 2016, Class FM, Hungary’s most popular commercial radio channel, was taken off the air. The Media Council of Hungaryʼs National Media refused to renew its licence as Class FM was owned by Hungarian oligarch Lajos Simicska, whose outlets became very critical towards the government after a quarrel between him and Orbán.

The authorities in Romania and Bulgaria might not follow a well-wrought plan, but the situation for critical journalists is as severe. “The main problem is that most outlets can’t generate enough revenue from the market,” Sipos explains. “These outlets found themselves under constant pressure, as powerful business people are willing to purchase them and use them to promote their own political agendas.” Ultimately, this issue leads to the demise of independent reporting and weakens voices critical of the ruling parties and influential political players.

Sipos concludes that “these three countries have little to no tradition of independent journalism.” Although death threats towards, or even violence against journalists do not exist, the working conditions for critical reporters are difficult.

He recommends the investigative outlets Bivol.bg from Bulgaria, atlatszo.hu and Direkt36.hu from Hungary as well as RISE Project and Casa Jurnalistului from Romania as bastions of independent journalism. A few mainstream outlets that conduct critical reporting are 444.hu, index.hu, HotNews.ro and Digi24.

Layli Foroudi, a youth board member from the UK, interviewed Mitra Nazar, MMF correspondent for Serbia, Kosovo, Slovenia and the Netherlands.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

This year, Serbia has been the most intense of the four countries to cover. Serbian journalists have been subject to physical attacks and the government has maintained a smear campaign against independent media outlets in the country.

“This is a very organised campaign,” explains Nazar, “they’re being called foreign spies and foreign mercenaries.”

The “foreign spy” accusation has a real effect on the personal safety of journalists, whose pictures are often published alongside such accusations in the pro-government media. Nazar, who wrote a feature on the subject, says that this can cause such journalists to be branded as unpatriotic and anti-Serbian: “When the government accuses journalists of being “foreign spies”, it gives the impression that these independent journalists are against Serbia as a country.”

The ruling party of Serbia even went so far as to organise a touring exhibition called Uncensored Lies, where the work of independent media was parodied in an attempt to prove that the government does not censor, however, the exhibition also served to discredit these publications by calling the content “lies”.

“Can you imagine the ruling party organises an exhibition discrediting independent media,” says Nazar, shocked, “this is not indirect censorship, it is directly from the government.”

The media landscape in the Netherlands does not experience direct state-sponsored censorship, but there are other challenges. The Netherlands ranks 2nd in the 2016 RSF World Press Freedom Index, but Nazar has still reported a total of 49 incidents since the Mapping Media Freedom project started, from police aggression against journalists, to assaults on reporters during demonstrations, to broadcasters being denied access to public meetings.

For 2017, she is interested in looking into how the Dutch media deals with the rise of the far right and a growing anti-immigrant sentiment, especially in the upcoming elections which will see controversial far-right candidate Geert Wilders stand for office.

Last year, a Dutch tabloid De Telegraaf published an article about the arrival of refugees to the Netherlands with a sensational headline that generated a lot of debate in the Dutch media, which Nazar says is becoming increasingly politicised and polarised.

For Nazar, there is a line to be drawn with what legacy media outlets should and should not publish. “That line is representing and following the facts,” she says, “if you publish a headline that says there is a “migrant plague”, that is beyond facts – it is a political agenda.”

The youth board’s Ian Morse, from the USA, interviewed Vitalii Atanasov, the MMF correspondent for Ukraine.

In just the past two months in Ukraine, journalists have been assaulted, TV stations have been banned and governments on both sides of the country’s conflict with Russia have sought to limit public information and attack those who publicise.

Vitalii Atanasov is the correspondent who reported these incidents to the Mapping Media Freedom project. Drawing on sources from individual journalists to large NGOs, Atanasov monitors violations of media plurality and freedom in Ukraine for the project. To verify a story, he sometimes contacts media professionals directly, or crowdsources through social media, as he finds that all journalists publicise cases of violation of their rights, attacks, and incidents of violence.

“Some cases are complicated, and the information about them is very contradictory,” Atanasov tells Index. “So I’m trying to trace the background of the conflict that led to the violation of freedom of expression and media.”

Many of the violations that occur in Ukraine are either individual attacks on media workers by separatists in the east or Ukrainian officials attempting to control the media through regulation and licensing.

Of about a dozen and a half reports since he began working with MMF, Atanasov says many reports stick out, such as the “blatant” attempts of authorities to influence the work of major TV channels such as Inter and 1+1 channels. Most recently, Ukraine banned the independent Russian station Dozhd from broadcasting in Ukraine. While TV has recently been the target, problems with media freedom have come from almost everywhere.

“The sources of these threats can be very different,” Atanasov says, “for example, representatives of the authorities, the police, intelligence agencies, politicians, private businesses, third parties, criminals, and even ordinary citizens.”

Atanasov and MMF build off the work of other groups working in Ukraine, such as the Institute of Mass information, Human Rights Information Center, Detector Media, and Telekritika.ua.

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1486659943480-96bea7cd-9879-6″ taxonomies=”6514, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Guest Post, News and features

World leaders march in Paris following the recent attacks in France (Photo: European Council)

Jacob Mchangama is the founder and executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law. He has written and commented on human rights in international media including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The Economist, BBC World, Wall Street Journal Europe, MSNBC, and The Times. He has written and narrated the short documentary film “Collision! Free Speech and Religion”. He tweets @jmchangama

The brutal attack against Charlie Hebdo has seen European leaders rally round the fundamental value of freedom of expression.

French President Francois Hollande led the way by stating: “Today it is the Republic as a whole that has been attacked. The Republic equals freedom of expression.” Prime Minister David Cameron vowed that Britain will “never give up” the values of freedom of speech, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel called the events in Paris “an attack on freedom of expression and the press — a key component of our free democratic culture.” European Union President Donald Tusk stressed that “the European Union stands side by side with France after this terrible act. It is a brutal attack against our fundamental values, against freedom of expression which is a pillar of our democracy.”

This unified commitment to freedom of expression is both admirable and crucial in the aftermath of the killing of cartoonists armed with nothing more than ink, humour and courage. It is also true that freedom of expression is a fundamental European value and that (Western) Europe allows for a much freer debate than most other places in the world. However, European governments and institutions have long compromised this freedom through statements and laws that narrow the limits on permissible speech. Ironically some of these statements and laws target the very kind of offence that Charlie Hebdo excelled in.

Donald Tusk’s principled defence of freedom of expression stands in stark contrast to a 2012 joint statement issued by then EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton, as well as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League that “condemn[ed] any advocacy of religious hatred … While fully recognising freedom of expression, we believe in the importance of respecting all prophets”. The statement followed the furore over the crude anti-Islamic film “The Innocence of Muslims”, and suggests that mocking prophets is tantamount to religious hatred prohibited under international human rights law and thus exempted from the protection of freedom of expression.

The controversy over The Innocence of Muslims prompted none other than Charlie Hebdo to print its own depictions of Mohammed, including one showing Islam’s prophet naked. That decision drew stern condemnations from the French government. Then Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius remarked that “in the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?”

While Charlie Hebdo has won a number of lawsuits other French figures have been convicted or censored under French law. Last year comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala was banned from performing his comedy shows publicly, due to their anti-semitic content. And France is not alone. Swedish shock artist Dan Park was sentenced to six months imprisonment in 2014, over a number of purportedly racist posters deemed “gratuitously offensive” to minority groups by a Swedish court. The owner of the gallery that had displayed the cartoons was also convicted and the posters ordered destroyed.

In 2011, a prominent Austrian Islam-critic was convicted of “denigration of religious beliefs” for stating that the prophet Mohammed “had a thing for little girls”. An elderly Austrian man was found guilty of the same offence for yodelling while his Muslim neighbour was praying. In the United Kingdom, an atheist who left caricatures of the Pope, Mohammed and Jesus in a prayer room in John Lennon Airport was similarly convicted and sentenced to six months imprisonment, though the sentence was suspended. A TV personality’s disparaging social media comments about Scotland and Scots recently prompted Scottish police to tweet that it would “thoroughly investigate any reports of offensive or criminal behaviour online and anyone found to be responsible will be robustly dealt with”.

France and numerous other European countries also have bans against Holocaust denial. In 2010, a Muslim group claiming to expose free speech double standards in the aftermath of the Danish cartoon controversy was convicted after publishing a cartoon suggesting that Jews have made up the Holocaust.

When it comes to countering terrorism, European states increasingly target not only expression that incites terrorism but also expression that may constitute “glorification”. Exactly a week after the attack against Charlie Hebdo, Dieudonné once again ran afoul of the law and was detained over a Facebook post. According to Le Monde at least 50 other cases of terror apology have been opened against people in France since the attack. In Denmark, a number of Islamists have been prosecuted for glorifying terrorism following Facebook postings that seemingly approved of terrorism, including the assault on Charlie Hebdo. Recently British Home Secretary Theresa May unveiled plans that would ban “non-violent extremists” from using television and social media to spread their ideology.

While Europe has a sophisticated and elaborate regional system for the protection of human rights, these institutions have frequently sided with the censors over citizens. In 2008 the EU adopted a framework decision obliging all member states to criminalise certain forms of hate speech. The European Court of Human Rights has found the confiscation of a “blasphemous” film, the conviction of a French cartoonist mocking the victims of 9/11, and the banning of religious fundamentalist group Hizb-ut-Tahrir compatible with freedom of expression. The Council of Europe’s current High Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks, has called for all 47 member states to enact bans against Holocaust denial and gender based hate speech.

These non-exhaustive examples demonstrate that contemporary Europe’s approach to freedom of expression is far more complicated and far less principled than the statements made by its leading politicians in recent days suggest. It is an approach to freedom of expression based on the premise that social peace in increasingly multicultural societies requires restrictions on freedom of expression in order to avoid offending ethnic and religious groups. Thus in 2004, when Dutch film maker Theo Van Gogh was murdered by an Islamist offended by Van Gogh’s controversial and anti-Islamic film “Submission”, the Dutch minister of justice proposed to revive the country’s blasphemy law which had been disused since 1968. He argued that “if opinions have a potentially damaging effect on society, the government must act … It is not about religion specifically, but any harmful comments in general.”

Such sentiments might appeal to pragmatists in the wake of the tragedy in France. But there is little reason to think that restricting freedom of expression fosters tolerance and social cohesion across a Europe increasingly divided along ethnic and religious lines, and where anti-semitism and other forms of intolerance is on the rise. In fact such laws seem to fuel the feeling of separateness of modern Europe by legally protecting group identities against offence rather than fostering an identity rooted in common citizenship. While minorities may be offended by disparaging comments, insisting that freedom of expression be limited to protect them from racism and offence, is a very dangerous game at a time where far-right movements with questionable commitment to liberal democracy are on the rise. In this context it should not be forgotten that Dutch politician Geert Wilders once proposed banning the Quran and that the leader of Front National Marine Le Pen wants to ban religious head wear, including the Jewish kippah. The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence. Only by reaffirming a genuine and principled defence of freedom of thought, expression and religion can Europe hope to create a society built on real tolerance and respect for diversity, and where cartoonists neither have to fear gunmen nor jail, but only the moral judgment of their fellow citizens.

This guest post was published on 16 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala has been banned from entering the UK. The French comedian has long been a controversial figure in his home country, but he became internationally known when West Bromwich Albion striker Nicolas Anelka celebrated a goal with the now infamous quenelle — a sort of inverted nazi salute created by Dieudonné, his friend.

Dieudonné argues he is simply standing up to the establishment, and that the quenelle is an anti-establishment gesture. The facts tell a different story. He has made a number of clearly antisemitic comments, and has been convicted in France of inciting racial hatred.

Dieudonné was set to visit the UK to support Anelka, who has been charged by the Football Association over the incident, and faces a minimum five-match ban. As a colleague pointed out, it’s unclear how, exactly, further links to Dieudonné would help Anelka, but that is now beside the point, as he has been “excluded from the UK at the direction of the Secretary of State”. A letter from the Home Office, obtained by Swiss newspaper Tages-Anzeiger, states that he should not be allowed to board carriers to the UK. If he gets as far as the border, he’ll be turned away at the door, as it were.

But Dieudonné is not alone. Over the years, a number of controversial speakers, covering pretty much the entire spectrum of extremist ideologies, have been banned from entering the UK. The reasons given from the Home Office are almost always along the vague lines of the person in question not being “conducive to the public good”. Below are some the most high-profile cases.

Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer

(Image: Mark Tenally/Demotix)

The American “counter-jihadists” were last May invited to speak at an EDL rally in Woolwich, London, at the scene of the brutal murder of Drummer Lee Rigby. However, they both received letters from the Home Office, informing them that based on past statements they were barred from entering the UK. One of Geller’s comments highlighted was: “Al-Qaeda is a manifestation of devout Islam… It is Islam.” In a joint statement, they declared that “…the British government is behaving like a de facto Islamic state. The nation that gave the world the Magna Carta is dead”.

Geert Wilders

(Image: Frederik Enneman/Demotix)

In 2009, leader of the far-right Dutch Party for Freedom was set to travel to the UK to show his controversial film Fitna — which has been widely labelled as Islamophobic — in the House of Lords. Despite being told by the Home Office before travelling the he was barred from entry because his views “threaten community harmony and therefore public safety”, he still flew to Heathrow, where he was eventually stopped at the border. “Even if you don’t like me and don’t like the things I say then you should let me in for freedom of speech. If you don’t, you are looking like cowards,” was his message to British authorities at the time. The decision was later overturned.

Fred Phelps and Shirley Phelps-Roper

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The father and daughter, both members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church — know, among other things, for picketing funerals — were planning on coming to Leicester to protest against a play about a man killed for being gay. The UK Border Agency said at the time: “Both these individuals have engaged in unacceptable behaviour by inciting hatred against a number of communities.”

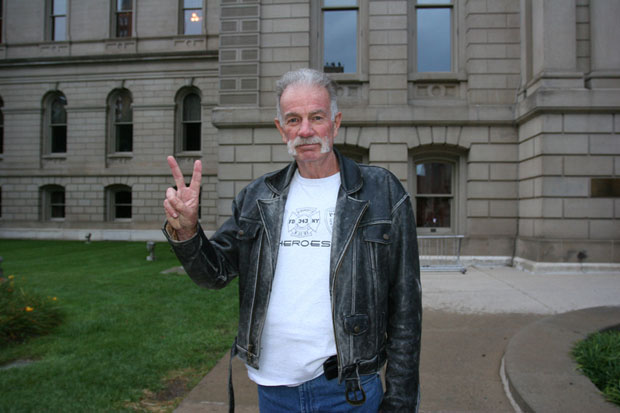

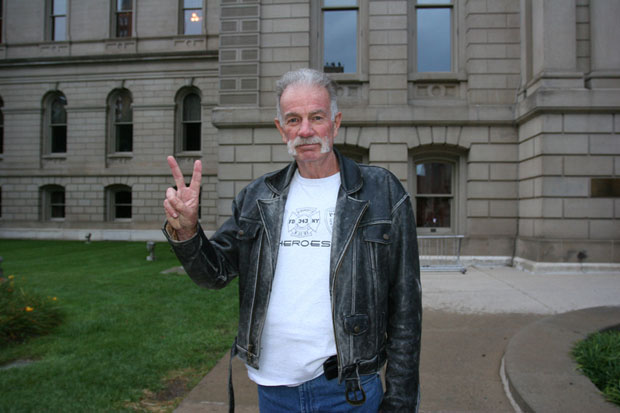

Terry Jones

(Image: Mark Brunner/Demotix)

The American pastor became known across the world when he threatened to stage a mass burning of the Koran in 2010 to mark the anniversary of 9/11 — something which in the end did not take place. In 2011 he was invited to attend a number of demonstrations with far right group England Is Ours. However, he was banned by the Home Office, which cited “numerous comments made by Pastor Jones” and “evidence of his unacceptable behaviour”. Jones responded saying: “We feel this is against our human rights to travel and freedom of speech.”

Dyab Abou Jahjah

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The then Belgium-based founder of the Arab European League spoke at a meeting of the Stop The War Coalition in March 2009. He left the country with the intention of coming back after a few days, only to discover that he was barred from entering Britain. His organisation had previously published “a series of antisemitic and Holocaust revisionist cartoons in response to the Danish Muhammad cartoons controversy.” Around the time of his visit, the president of the Board of Deputies, Henry Grunwald QC, wrote to then-Home Secretary Jacqui Smith “raising concerns about Jahjah”. In a post on his website, he said he believed his ban was “mainly to do with the lobbying of the Zionists”.

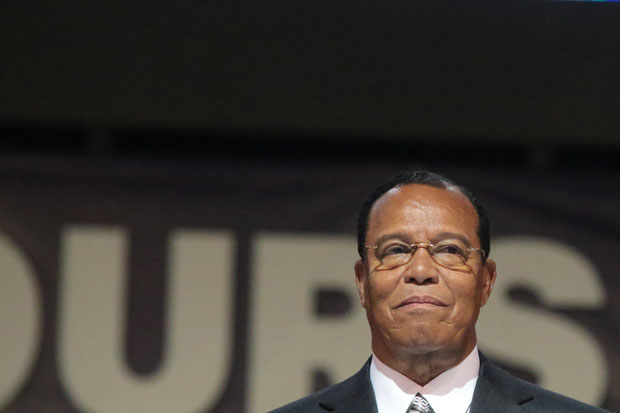

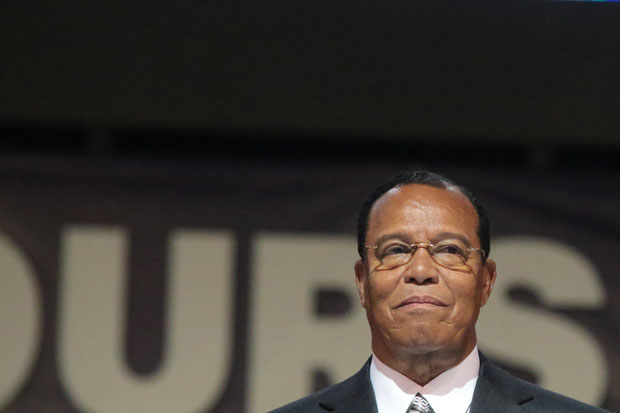

Louis Farrakhan

(Image: Thabo Jaiyesimi/Demotix)

The American Nation of Islam leader has been banned from entering the UK since 1986, due to racist and antisemitic remarks like calling Jews “bloodsuckers” and Judaism a “gutter religion”. The ban was briefly overturned in 2001 by a High Court ruling, but the government won out in the Appeals Court the following year.

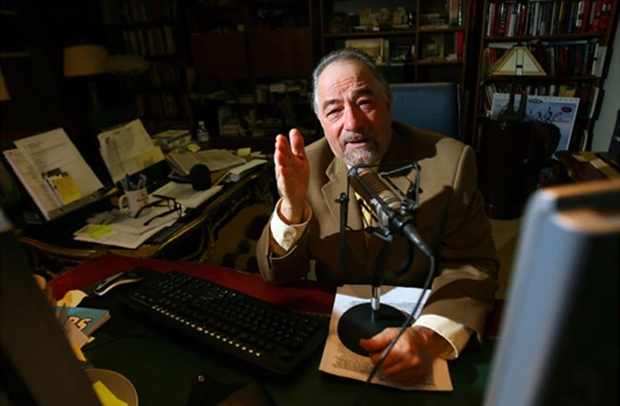

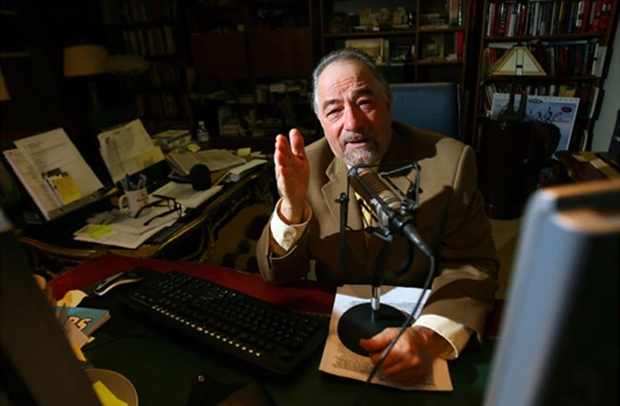

Michael Savage

(Image: Clifford Dombrowski/YouTube)

In 2009, then Home Secretary Jacqui Smith announced a 16-person banned-list, made public in a bid to explain the authorities reasoning for barring people from entering the country. On the list was shock-jock Savage — a popular American talk radio host, who has outraged listeners with comments like “Latinos ‘breed like rabbits'” and “Muslims ‘need deporting'”. He was banned for being “likely to cause inter-community tension or even violence”. Savage reacted with disbelief, claiming he would sue Smith. The ban was reaffirmed in 2011.

This article was originally posted on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”. As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria. A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.