16 Jan 2020 | Index in the Press

Index on Censorship, Reporters Without Borders UK, and Transparency International UK are asking Azerbaijani authorities to reconsider a travel ban on prominent journalist Khadija Ismayilova so she can give evidence in the trial of a Romanian journalist, a press release said. Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg said the travel ban on Ismayilova was “a means to punish her and stifle the spread of her reporting.”

Read the full story here.

16 Jan 2020 | Index in the Press

Three nongovernmental organizations are urging Azerbaijan to lift a travel ban against investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova and allow her to travel to Britain to give evidence in the trial of a journalist who is being sued for defamation by an Azerbaijani lawmaker…

In a joint statement on January 15, Index on Censorship, Reporters Without Borders U.K., and Transparency International U.K. said lawyers will be seeking permission for Ismayilova to travel to London, where the case against Romanian journalist Paul Radu is set to start next week.

Read the full story here.

15 Jan 2020 | About Index, Azerbaijan, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Press Releases

Azerbaijan authorities should lift a travel ban against award-winning investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, UK-based rights groups urged on 15 January.

Ismayilova was detained in December 2014 and sentenced in September 2015 to seven-and-a-half years in prison on trumped-up charges. She was conditionally released in May 2016, but three-and-a-half years later, still remains subject to a travel ban and has been unable to leave the country despite numerous applications to do so.

Lawyers will be seeking permission for Ismayilova to travel to the UK to give evidence in the trial of Paul Radu, a Romanian journalist who is co-founder and executive director of investigative reporting group OCCRP (the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project). Radu is being sued for defamation in London by Azerbaijani MP, Javanshir Feyziyev, over two articles in OCCRP’s award-winning Azerbaijan Laundromat series about money laundering out of Azerbaijan.

Ismayilova, OCCRP’s lead reporter in Azerbaijan, is a key witness in the case.

“Azerbaijan is unjustly and unfairly preventing Khadija Ismayilova from travelling internationally as a means to punish her and stifle the spread of her reporting,” said Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg. “Given the UK’s stated commitment to speak out more publicly on threats to media freedom, we urge Britain to join our calls for Ms Ismayilova to be released from her travel ban.”

As UN special rapporteur David Kaye wrote in 2017, travel bans “deny the spread of information about the state of repression and corruption” in countries and act as a form of censorship. In 2017, Ms Ismayilova was prevented from travelling to receive the Right Livelihood Award, the alternative Nobel Prize, for her reporting in Azerbaijan.

“This travel ban is one of many examples of the Azerbaijani authorities’ longstanding persecution of Khadija Ismayilova for her courageous investigative reporting, and she is one of dozens of journalists and activists currently subjected to such measures in Azerbaijan. The ban should be immediately lifted, she should be acquitted of the bogus charges it stemmed from, and she should be allowed to travel to give testimony in this alarming case against another investigative journalist,” said Rebecca Vincent, UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders.

The case against Paul Radu will commence on 20 January.

“Thanks to reporting by Khadija Ismayilova and her colleagues, we know more about how money stolen from the people of Azerbaijan has found its way into luxury London property,” said Daniel Bruce, Chief Executive of Transparency International UK. “Preventing her from giving evidence is a clear attempt to bully and silence those who dare expose the truth. As a defender of free speech and the rule of law, the UK Government should call for her freedom to travel to Britain to provide evidence in this important libel case.”

3 Jan 2020 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

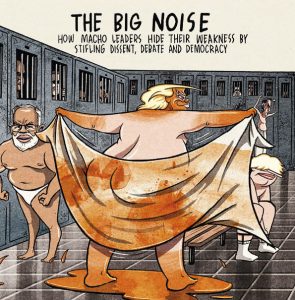

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-bKFo30o2o”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]What does it mean to be a man? That has been the subject of many a song and is also the subject of the winter 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, where we consider how leaders are using concepts of masculinity for their political gain and our free speech loss. While you’re reading the mag, have a listen to your playlist which features artists from Bob Dylan to Taylor Swift, who are all singing, one way or another, about the problems with macho men.

Enjoy the songs below. Hopefully the outspoken lyrics of women like Lily Allen and Shania Twain will leave you feeling more empowered than despondent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When US President Donald Trump tweeted that he is “so great looking and smart”, Carly Simon’s classic take down of an unnamed man sprung to mind. Ditto every time we see Russian President Vladimir Putin’s appearing topless on a horse. But what are these mega egos doing to our rights? Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley spoke to New York Times lawyer David E. McCraw about the state of media freedom in the USA under Trump.

“Macho, macho man! I want to be a macho man!” Is this what the current pack of male leaders listen to every morning? And do they also add their own words, like dominant, aggressive and infallible? For a more complete list of what they are like, how they are destroying our freedoms and how you can be a macho man too, read Rob Sears guide for the modern despot.

Brandon Flowers told NME in 2017 that the then-newly released single The Man depicted his attitude towards masculinity when The Killers started out, an attitude he now regrets. With lyrics including “don’t try to teach me, I got nothing to learn”, it’s easy to see why Flowers is glad to have grown out of such youthful notions. Unfortunately, the men who dominate world politics don’t seem to have matured out of their eagerness to be “The Man” and all that that implies. Case in point China’s Xi Jinping.

Irish rock band Thin Lizzy had a hit in 1976 with The Boys are Back in Town, a joyful ode to, well, boys being back in town. Its catchy melody means it’s still a feature on many party playlists, but delve into the lyrics and evidence of toxic masculinity is there. When the boys go out, “The drink will flow and the blood will spill, And if the boys want to fight, you better let ’em”. Kaya Genç reports on a rap collective in Turkey using music to take down that kind of ‘masculine’ behaviour men can exhibit.

While “lion man” is used with some irony by Mumford and Sons in this song, to show a man who hides his insecurities behind a facade of machismo, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro does not appear to exhibit any irony when he refers to himself as a majestic lion surrounded by hyenas, as he did last year. Stefano Pozzebon reports on the uphill battle faced by the Brazilian press to hold this lion to account.

Bob Dylan’s moving, acoustic attacks on macho world leaders sending young people off to spill their blood on the battlefield are timeless. “When the death count gets higher, you hide in your mansion” sings Dylan in Masters of War. Somak Ghoshal reports on India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is a fervent patriot with a strong war cry.

Macho leaders are eager to impress, whether it be to their citizens in a bid to maintain fearful respect and loyalty or fellow world leaders who they want to come across as heads of powerful states not to be underestimated. What would Canadian powerhouse Shania Twain say? If this song is anything to go by, they don’t impress her much. Arrogant intelligence, vanity and fast cars are all big no-nos, and we’d assume draconian policies and the quashing of free expression are too. It’s bad news for Tanzania’s “Bulldozer” President Magufuli.

Did Lily Allen write her song Fuck You with Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán in mind? The song takes aim at small-minded, hate-filled, racist homophobes, with lines like “So you say it’s not OK to be gay, well I think you’re just evil”, which could be one way to address a leader whose party continues to assault gay rights by promoting “family values” that exclude LGBT people.

Taylor Swift captures the inequalities between the sexes in The Man, her song about the respect she would get if she was a man for the same actions that result in criticism for a woman. Female journalists could sing the same song, often being targeted as much for their gender as for their words. Miriam Grace Go reports on Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte, for example, and his explicit denigration of female journalists and politicians.

No-one writes a protest song quite like Pussy Riot, the Russian feminist punk rock group. In October 2016, two weeks before Donald Trump was elected as US president, they released Make America Great Again, a dystopian vision of the USA under Trump. Lyrics include “Can you imagine a politician calling a woman dog?” Unfortunately, we don’t have to imagine this as it’s become all too real. Caroline Lees reports on how world leaders are using slurs to undermine their opponents in a trend that appears to be getting worse.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]