17 Jun 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, Index Reports

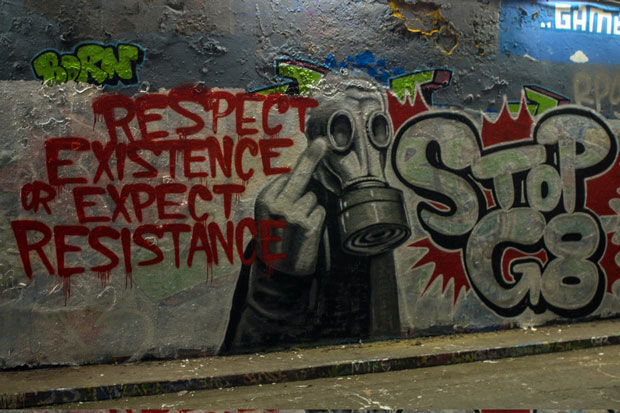

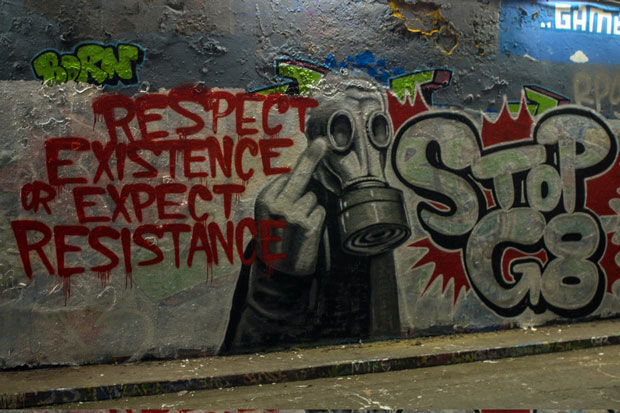

Stop G8 graffiti in London. (Photo: David Rowe / Demotix)

When G8 leaders meet in Northern Ireland today, they will focus on transparency, trade and development. But they cannot hope to achieve their declared goals on transparency, corruption and human rights without a clear commitment to respecting freedom of expression at home. Sean Gallagher writes

While the G8 nations generally perform well in indicators of media freedom, digital freedom and civil liberties more widely, there are some key weaknesses including constraints on the media, and digital surveillance. Russia is an outlier with a deteriorating record on free expression with the Russian government having increasingly pursued a course of restrictions on speech and free assembly.

While most of the G8 stand for digital freedom internationally, the Prism revelations drastically undermine the US stance in favour of an open internet on the international stage. Revelations that some of the G8 nations – generally seen as having the freest media, open digital spheres and a supportive artistic environment – have engaged in ongoing, intrusive and secret population-wide surveillance is deeply concerning. All of these nations are pledged to uphold the right of the individual to the freedom of expression through either native legislation or international agreements.

The G8’s emphasis on transparency at its Northern Ireland meeting is welcome – not least since one of the areas of considerable concern and varying performance across the G8 is corruption. Most of the G8 perform relatively well on corruption (though not as strongly as might be hoped for), Italy lags behind the US, Canada, Germany, UK, France and Japan to a striking degree, while Russia’s ranking is one of the worst internationally (as shown in table one).

How the G8 nations stack up against each other on media freedom

In terms of media freedom Germany and Canada come first (according to Reporters without Borders 2012 index). The United Kingdom and the United States are behind these two but still ranked fairly highly while France, Japan and Italy lag behind these four a bit more. Russia is substantially lower indicating a weak and deteriorating environment for media freedom.

The press freedom measurements only give a snapshot of the G8 nations. Briefly, here are the key issues affecting the media in the G8 nations.

Germany’s media is largely free and the legal framework protects public interest journalism. Germans are ill-served by their country’s lack of plurality in broadcast media.

In Canada, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression and other observers have found that access to information has become more difficult since Conservative Stephen Harper became prime minister in 2006 – particularly when it comes to climate change. The country’s hate speech laws and lack of protection for confidential sources are issues our research highlights.

The United Kingdom’s move to reform libel laws is a clear positive for free press and expression, a change that our organisation helped deliver. Cross-party proposals to introduce statutory underpinning for media regulation via the Royal Charter on the Regulation of the Self-Regulation of the Press cross a red line by of introducing political involvement into media regulation. The shelving of the Communications Data Bill, or “Snooper’s Charter”, is also an encouraging sign, although a number of politicians are still calling for its reintroduction — especially after the Woolwich attack — which raises more questions.

In the United States, recent Prism revelations of the Obama administration’s continued surveillance both around the world and of the American people through secret subpoenas raise serious questions about the government’s activities. Alleged mistreatment of “tea party”-related organisations by the Internal Revenue Service also embroiled the Obama administration in questions about its commitment to transparency.

France’s media is generally free and offers a wide representation among political viewpoints but there is unwelcome government involvement in broadcasting and the country’s strict privacy laws encourage self-censorship. Here, too, government surveillance has increased and politicians have used security services to spy on journalists.

While Japan’s press environment can be called free, self-censorship is rife and rules detailing “crimes against reputation” are enshrined in the constitution. Compounding these issues is the cozy relationship between government and journalists. The government’s poor transparency on the nuclear crisis at Fukushima has been singled out as a contributing factor to its decline in international rankings.

Italy’s media environment is robust in some ways but is hamstrung by political involvement in ownership and high media concentration in too few hands (not least by former PM Berlusconi). The country’s leaders are also adept at using the media in support of their own agendas.

Never a beacon for a free media, Russia has experienced an outright government takeover of the major broadcasting outlets and widespread violence and threats against journalists. When compared to the rest of the G8, Russia’s record is decidedly bad although censorship is not at the level of China (which does not though claim to be a democracy).

Citizen Surveillance on the Digital Frontier

The digital freedom index created by Freedom House is another useful indicator although it encapsulates many different dimensions into just one number. The US and Germany perform strongly in this index, with Italy and the UK somewhat behind. Russia’s ranking is very low. However, the Prism affair surely more than dents the US ranking – and shows how hard it is to combine surveillance and censorship (and other aspects of digital freedom) into one index.

The UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression Frank La Rue issued a timely report on government surveillance, privacy and freedom of expression ahead of the revelations of massive and appalling data mining carried on by the US government under the cloak of secrecy. This is a clear breach of transparency and digital freedom on a global scale.

While the US and European countries have been pushing back against the Russian and Chinese model of top-down internet governance, the widespread moves toward online surveillance undermines their efforts to ensure a multistakeholder approach to the web as part of the ITU process.

Though the US leads the world on Google requests for user data (a number that now seems just the tip of the iceberg in comparison to the Prism revelations), the G8 nations do not approach the levels that Brazil and India reach on demanding content be removed from the search engine.

The United States government has granted itself unprecedented powers to snoop on its citizens at home and abroad. First, the PATRIOT Act, parts of which were renewed in 2011, gave the US government unprecedented power to intrude into the online lives of its citizens in extra-judicial ways. Later, in 2008, Congress approved the FISA Amendments Act, which envisioned the Prism and other programmes described in articles released by The Guardian and the Washington Post. Despite this, several bills that would have given the government additional powers in the area of surveillance and copyright infringement have been withdrawn after concerted campaigns by internet and civil society activists.

The United Kingdom has stepped back recently from mass population surveillance with the shelving of the Communication Data Bill. But revelations of data-sharing activities with its US partner, as reported by The Guardian suggest we do not have the full picture. Beginning with the 2000 Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act and continuing with the recently shelved Communication Data Bill, successive governments have looked to surveillance of online activity in the name of national security. On a more positive note, interim guidelines on prosecutions of offensive speech on social media have been issued with the aim of hemming in criminal prosecutions, though restrictions on “grossly offensive” speech are still on the statute book. Takedown requests aimed at Google and Twitter are of a level comparable to France and Germany.

Japan is generally seen as having a positive record on digital freedom despite the government’s pressure to force telecom companies to remove “questionable” material from the web in regard to the Fukushima crisis. The country also instituted a strict piracy law at the behest of the Recording Industry of Association of Japan.

While Italy has generally been slower to adopt new technology, Italians internet users are bound by rules on data retention that can be seen as a threat. The regulations allow the government to target criminals and protect national security, yet do not guarantee the privacy of the data it collects. Italy has strict copyright and piracy legislation. Most worrying is the conviction of Google executives for violation of privacy laws due to material posted to the search engine giant by a third party.

Germany’s approach to digital rights is regarded as open and courts have ruled that access to the internet is a basic human right. But in 2011, German authorities acquired the license for a type of spyware called FinSpy, produced by the British Gamma Group. Hate speech laws are beginning to have an impact on digital free speech.

In France, online surveillance has been extended as a result of a 2011 anti-terror law and Hadopi 2 (the law “promoting the distribution and protection of creative works on the Internet”) which is supposed to reduce illegal file downloading. Hadopi 2 makes it possible for content creators to pay private sector companies to conduct online surveillance and filtering, creating a precedent for the privatisation of censorship. Another 2011 law requires internet service providers to hand over passwords to authorities if requested.

In Canada, too, the right to free expression online is coming under increased pressure. On a positive note, civil society activists were able to derail the Conservative government’s attempt to obtain online activity records without judicial oversight. Yet, the Canadian government recently introduced a law requiring librarians to register before posting on social media without first registering for either personal or professional use.

Though Russia’s online environment is relatively open, the government has been tightening restrictions leading to blocking of websites. The government claims this is to tackle crime and illegal pornography. However there are fears that it will apply the regulations too broadly and damage free expression in the digital realm through the creation of extra judicial block lists and censorship of content.

Muzzling Artistic Expression

While most of the G8 have a wide ranging and often vibrant artistic sphere, there are many pressures that can lead of censorship or self-censorship whether from public order, obscenity or hate speech laws or from self-censorship including especially timidy by arts institutions. As Index on Censorship noted in its recent conference report on artistic expression in the UK, institutional filters are stifling creativity. The same can be said for the arts in the other G8 nations, though for different reasons. The specific reasons for brakes on creativity will be explored more fully in each of the country reports. But common themes emerge around hate speech, fear of offence and budget constraints that force arts organisations to shy away from controversial works. Arts funding continues to be used as a political weapon in some countries. In Russia, artists must avoid offending the sensibilities of government partners like the Russian Orthodox Church — as in the Pussy Riot prosecution.

7 Jun 2013 | In the News

AZERBAIJAN

Europe criticizes Azeri leader over Internet defamation law

European institutions criticized Azeri President Ilham Aliyev yesterday for signing legislation making defamation over the Internet a criminal offence punishable by imprisonment as the country prepares for an autumn presidential election.

(Free Malaysia Today)

EGYPT

Columnist sentenced to prison for libel

Writer Osama Ghareeb did not know he had already been sentenced to one year in prison by a Cairo court until being summoned to Moqattam Police Station on Wednesday, according to the writer’s Twitter account. (Daily News Egypt)

GLOBAL

Gallery: Five free expression exiles

IFEX marks World Refugee Day, 20 June 2013, with profiles of five people living in exile for practicing the right to free expression through their professions (IFEX)

INDIA

Safeguards needed to protect privacy, free speech in India: HRW

The Indian government should enact clear laws to ensure that increased surveillance of phones and the Internet does not undermine rights to privacy and free expression, Human Rights Watch said today. (Business Standard)

Standing up to censorship central

A recent judgment on the airing of ‘low value’ television programming misinterprets the proportionality doctrine and raises the question: should the state be giving advice to adults? (The Hindu)

MALAWI

(Censorship Board Says Does Not Regulate Material On the Internet

The Malawi Censorship Board has said it does not censor materials on the Internet because it is not mandated to do so.(AllAfrica.com)

NEW ZEALAND

Racial stereotypes pervade

It was interesting watching the response last week after cartoonist Al Nisbet was allowed to draw cartoon stereotypes in the Marlborough Express about Maori and Pacific Islanders. (Auckland Now)

SINGAPORE

Web ‘blackout’ in Singapore to protest new online rules

Over 130 Singaporean bloggers blacked out their homepages Thursday to protest new licencing rules for news websites they say will muzzle freedom of expression. (NDTV)

TURKEY

Protests expose the extent of self-censorship in Turkish media

Only days after Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan called social media “the worst menace to society”, the country arrested 25 social media users in Izmir for allegedly “spreading untrue information” on Twitter. Sara Yasin gives a rundown on Turkey’s Twitter phobia. (Index on Censorship)

Turkey’s prime minister vows to continue Gezi Park development

Despite mass protests, Recep Tayyip Erdogan to push ahead with construction, saying it will make Istanbul more beautiful (The Guardian)

UKRAINE

Censorship by violence

One of my friends recently told me a story about the son of her friends. He had to be taken to a psychologist after watching news on TV about a mother killing her child. (Kyiv Post)

UNITED STATES

Documents: U.S. mining data from 9 leading Internet firms; companies deny knowledge

The National Security Agency and the FBI are tapping directly into the central servers of nine leading U.S. Internet companies, extracting audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track foreign targets, according to a top-secret document obtained by The Washington Post. (Washington Post)

Drawing Line On Free Speech

The freedom to say what we think, no matter how repugnant to others, is one of the greatest glories of our system of government. It also is the foundation supporting our other liberties. (The Intelligencer)

Lindsey Graham Hates Free Speech

Are we starting to get under the skin of U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham (RINO-S.C.)? At first glance it would appear that way … Graham, a frequent target of this website’s criticism (due to his frequent awfulness), suggested this week that bloggers don’t deserve one of the most basic freedoms guaranteed to all Americans under the U.S. Bill of Rights.

(Fits News)

IRS Attorney Carter Hull Sent Targeted Letters to ACLJ Tea Party Clients from Washington, D.C.

The Wall Street Journal reports that transcripts of interviews by congressional staffers point the finger to IRS attorneys in Washington, further confirming that the targeting of conservative groups originated by the IRS in Washington, D.C. and that it was not the mistake of a couple of rogue, low level IRS agents in one Cincinnati office as the Obama Administration and the IRS continue to claim. (ACLU)

New York Post hit with libel lawsuit over ‘Bag Men’ Boston bombings cover

Two Massachusetts residents sue New York Post on claims it falsely portrayed them as suspects in Boston Marathon attack (The Guardian)

ZAMBIA

Kasonokomona Wins First Round of Court Battle

Zambian activist Paul Kasonkomona has won an important first round in his court battle. In an interview on Zambian television in April he called for the recognition of gay and lesbian rights, as well as the rights of sex workers. He was arrested after the interview and charged under section 178(g) of the Zambian Penal Code. (AllAfrica.com)

30 Apr 2013 | Digital Freedom

Washington DC was awash this weekend with some of the biggest names in journalism, technology, civil society and government — and not just for the star-studded White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

On Friday, Google hosted its first Big Tent event in DC with co-sponsor Bloomberg to discuss the future of free speech in the digital age.

Each panel was guided by hypothetical scenarios that mirrored real current events and raised interesting free speech questions around offence, takedown requests, self-censorship, government leaks, national security and surveillance. The audience anonymously voted on the decision they would have made in each case, but as Bill Keller, former executive editor at the New York Times, acknowledged, “real life is not a multiple choice question”. Complex decisions are seldom made with a single course of action when national security, privacy and freedom of expression are all at stake.

The first panel explored how and when news organisations and web companies decide to limit free speech online. Google’s chief legal officer David Drummond said that governments “go for choke points on the internet” when looking to restrict access to particular content, meaning major search engines and social media sites are often their first targets regardless of where the offending content is hosted online. Drummond said that Google is partially blocked in 30 of the 150 countries in which it operates and cited an OpenNet Initiative statistic that at least 42 countries currently filter online content. Much of this panel focused on last year’s Innocence of Muslims video, which 20 countries approached Google to review or remove. Drummond questioned whether democracies like the US, which asked Google to review the video, are doing enough to support free expression abroad.

Mark Whitaker, a former journalist and executive at CNN and NBC, said staff safety in hostile environments is more important in deciding whether to kill a story than “abstract issues” like free speech. Security considerations are important, but characterising freedom of expression as “abstract” and endorsing self-censorship in its place can set a worrying precedent. Bill Keller argued that publishing controversial stories in difficult circumstances can bring more credibility to a newsroom, but can also lead to its exile. Both the New York Times and Bloomberg were banned in China last summer for publishing stories about the financial assets of the country’s premier. This reality means that news organisation and web companies often weigh public interest and basic freedom of expression against market concerns. Whitaker acknowledged that the increased consolidation of media ownership in many countries means financial considerations are being given even greater weight.

The second panel debated free speech and security, with Susan Benesch of the Dangerous Speech Project standing up for free speech, former US Attorney General Alberto Gonzales coming down hard on the side of security, and current Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security Jane Holl Lute backing up Gonzales while recognising the vital role free speech plays in a functioning society.

In the first scenario posed to this panel, audience members were split on whether mobile networks should be shut down when a clear and imminent threat, such as the remote detonation of a bomb, arises. Lute said, “the first instinct should not be to shut down everything, that’s part of how we’ll find out what’s going on,” whereas Benesch focused on the civil liberties rather than surveillance implications of crippling communications networks.

In cases of extremism, which the panel agreed is often more easily and quickly spread via digital communications, Benesch endorsed counter speech above speech restrictions as the best way to defend against hate and violence. 94 percent of the audience agreed that social media should not be restricted in a scenario about how authorities should react when groups use social media to organise protests that might turn violent.

Google’s executive chairman Eric Schmidt closed the event by highlighting what he considers to be key threats and opportunities for digital expression. Schmidt believes that the world’s five billion feature phones will soon be replaced with smartphones, opening new spaces for dissent and allowing us “to hear the voices of citizens like never before”. Whether he thinks this dissent will outweigh the government repression that’s likely to follow is unclear.

Big Tent will make its way back to London next month where Google hosted the first event of its kind two years ago. The theme will focus on “innovation in the next ten years” with Ed Milliband, Eric Schmidt and journalist Heather Brooke as featured speakers.

Google is an Index on Censorship funder.

15 Apr 2013 | Newswire

Digital rights activists from around the UK met in Manchester for Open Rights Group’s first ever ORGCon North on Saturday.

John Buckman, chair of the San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), delivered the keynote speech: “Britain, under the thumb of…”

He filled in the blank with references to the copyright industry, the new Royal Charter on press regulation, overreaching child protection restrictions, the EU, the US, and private web companies, all of which pose significant challenges to digital freedom of expression in the UK.

The rest of the day was split between four panel sessions and eight impromptu “unconference” sessions for which participants pitched ideas and convened small groups to discuss them.

I spoke on a panel about the right to offend, alongside ORG’s Peter Bradwell and The Next Web’s Martin Bryant. Overly broad and outdated legislation, most notably Section 5 of the 1986 Public Order Act and Section 127 of the 2003 Communications Act, are regularly used to criminalise freedom of expression both online and offline in the UK. Despite a successful campaign to drop “insulting” words from the grounds on which someone can be prosecuted for offence under Section 5, the fact that neither of these provisions address the speaker’s (or tweeter’s) intentions continues to chill freedom of expression in the UK.

Also troubling is the fact that other states, India and the UAE for example, point to these and other British laws as justification to prosecute offensive expression in their own jurisdictions. I argued that protecting everyone’s fundamental right to freedom of expression is more important than protecting the feelings of a few people who might take offense to satirical, blasphemous or otherwise unsavoury views. For freedom of expression to be preserved in society, potentially offensive expression requires the utmost protection.

Another panel addressed the proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, which intends to strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995 and harmonise individual member states’ laws on data protection. Provisions in the proposal around consent, data portability and the “right to be forgotten” aim to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable for their use of it. Many companies that rely on user data oppose the regulation and have been lobbying hard against it with the UK government on their side whereas some privacy advocates argue it does not go far enough.

There were also discussions on the open rights implications of copyright legislation and the UK’s Draft Communications Data bill (AKA Snooper’s Charter), which looks set to make a comeback in the Queen’s speech on May 8.

The “unconference” sessions addressed specific causes for concern around digital rights in the UK and abroad. I participated in a session on strategies for obtaining government data in the UK and another on the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA) Amendments Act of 2008. This Act, along with the Protect America Act of 2007 legalised warrantless wiretapping of foreign intelligence targets. Digital rights activists took notice of the laws because the rise of cloud computing means even internal UK and EU data is potentially susceptible to US surveillance mechanisms.

Other “unconference” sessions focused on anonymity, password security, companies’ terms of service, activism and medical confidentiality.

The full OrgCon North agenda is available here. ORG’s national conference will take place on 8 June and will feature EFF co-founder John Perry Barlow who wrote the much circulated and cited “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” in 1996.

Brian Pellot is Digital Policy Adviser for Index on Censorship. Follow him @brianpellot