30 Aug 2011 | Americas, Mexico

Rumours about murdered reporter Humberto Millan Salazar have grown out of all proportion since his death last week. The journalist was kidnapped in the north-eastern state of Sinaloa, his body was found the same day. Millan Salazar was apparently killed just an hour after his kidnapping last Thursday, and had been executed with a 9mm gun. Friends and colleagues claim Millan Salazar was killed for political reasons. One website claims he was a supporter of the current governor of the state of Sinaloa, who belongs to a political party that last year defeated a candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) — the PRI has dominated Mexican politics for almost 70 years.

Sinaloa Governor Mario Lopez Valdez told reporters that the country’s Attorney General is sending three specialised investigators to investigate the case.

Millan Salazar was the director of the online magazine A-Discusion (Let’s Discuss) and wrote widely on government corruption. His last column was published on 23 August, a few days before his murder, and criticised the PRI’s President, Humberto Moreira, who had been accused of massive mismanagement of public funds in the northern state of Coahuila.

Sinaloa is home to the Sinaloa Cartel, a powerful drug gang led by kingpin Joaquin “Chapo” Guzman. Local sources claim Millan Salazar was caustic critic of local government but hardly touched on stories related to drug trafficking. A regional press group, Periodistas Siete de Julio has written an open letter asking for protection for the media. According to the letter, the murder of Millan Salazar demonstrates that there are sacred cows in the political spectrum of Sinaloa, things that cannot be talked or written about. A colleague has also announced that Millan left him a video where that contains tips about who could have murdered the reporter.

Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission says 71 journalists have been killed and 14 have disappeared since 2000. This week, another columnist, Enrique Ramirez of the blog Fuentes Fidedignas, said he was leaving Sinaloa because of death threats.

25 Aug 2011 | Americas, Mexico

[UPDATE] The Committee to Protect Journalists reports that Salazar was found dead early on Thursday 25 August in Sinaloa near the state capital, Culiacán, with a gunshot wound to the head.

Humberto Millán Salazar, a journalist from the north western state of Sinaloa, Mexico, was kidnapped yesterday. The 53 year old reporter has worked for local media for the last three decades. He is a reporter for a local website notoriously critical of Sinaloa’s local government. Salazar is also a radio broadcaster on Radio Formula, one of the top national radio networks in the country.

The Special Prosecutor for Crimes Against Freedom of Speech Gustavo Salas said 13 journalists had disappeared across the country since 2000. Salazar’s disappearance comes only a month after the disappearance and murder of another reporter in the southern state of Veracruz.

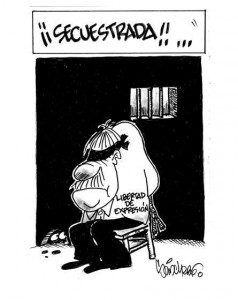

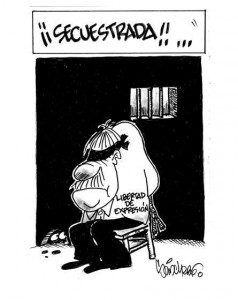

A local journalist group Periodistas Siete de Junio released a drawing on its Facebook page demanding the return of Salazar. The group also asked local authorities to ask for federal authorities to help them in the search of Salazar who was an active participant of the group.

15 Aug 2011 | Americas, Mexico

In a nation already accustomed to a high-levels of crime-related violence, the recent activities of a little known anarchist group have left Mexicans baffled. The explosion of a parcel bomb sent to a nanotechnology professor at the prestigious Tecnologico de Monterrey last Monday injected an element of magic realism to Mexico’s crime wave. Professor Armando Herrera Corral and another professor from the Tecnologico de Monterrey, Campus Estado de Mexico, were wounded when Corral opened a package that contained the rudimentary bomb. The anti-technology group that took credit for the attack, Individuals Tending to Savagery, opposes nanotechnology, the science that seeks to build machines in the size of molecules.

The attack against the Tec is seen as heresy, Mexico is very proud of this prestigious private university that styles itself after the Massachusetts Technology Institute (MIT). In April, the same group sent another parcel bomb to the Instituto Politecnico, a science polytechnic, the intended target was another nano scientist, but was accidentally detonated by a security guard who lost an eye in the incident.

The story took a lurid twist after speculation connected the case to the 5 August disappearance of scientist Yadira Davila Martinez, a genome specialist who vanished in a shopping mall in Cuernavaca, a town located an hour outside if Mexico City. The police have found a dismembered body they believe may be that of Davila Martinez and a final DNA identification is pending. Davila Martinez worked for the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, UNAM, Mexico’s country’s top public university. Her case might just be a coincidence — two drug groups are fighting a turf war in Cuernavaca — but if her case is linked to the anti-technology group, it would bring a dangerous new element to the Mexico’s violence. In the past other anarchist groups placed bombs at ATM tellers in Mexico City, but this is the first rash of serious attacks directed against individuals.

Individuals Tending to Savagery take their cue from Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber in the United States who engaged in a 20 year letter bombing spree against universities and companies he identified as degrading the environment. The attack has terrified the university community in Mexico City. Government officials have called on all institutions to upgrade their security.

5 Aug 2011 | Americas, Mexico

The recent murders of three journalists have spread fear throughout the small community of night police reporters in the coastal city of Veracruz, southern Mexico. All three victims worked for Notiver, a tabloid known for its lurid crime reporting. The latest murder, of journalist Yolanda Ordaz, created such collective fear that several journalists from both Notiver and other news outlets have fled the region in fear for their lives.

Causing outrage at Notiver, a statement from local authorities denied Ordaz’s murder was related to her work, claiming instead that there were indications her killing was connected to organised crime in the area.

Notiver itself has also received criticism. Media critic Marco Lara Klhar commented thatin continuing to publish lurid violent pictures and deriding local citizens such newspapers were putting their journalists at risk. He also lamented the government’s claim of the murders being connected to organised crime, predicting that the killings will remain unsolved.

Mexico remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for reporters, with seven journalists being killed in 2011 alone.