18 Aug 2014 | News and features, Poland, Religion and Culture

Ewa Wojciak has been working in the in theatre since the 1970s when she was a dissident artist under the communist regime. (Photo: Maciej Zakrzewski)

Ewa Wojciak, director of Poland’s Theatre of the Eighth Day, was fired by Poznan mayor Ryszard Grobelny on 28 July. His administration oversees culture and arts in the city, including Wojciak’s subversive and anti-establishment theatre group.

The official reason given was that she did not ask for permission to leave the city between 18 and 28 February, when she visited Yale and Princeton universities, performing her touring duties as director and actress with the theatre. However, these trips were not sponsored by the local government, so it is hard to see why she would need permission from authorities.

Wojciak’s career with the theatre began in 1970 when she was a dissident artist under the communist regime. After the end of communism, she turned the theatre into a welcoming space for refugees, minorities, anti-facists, feminists, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and emerging theatre-makers. She has become a “new dissident”, confronting the realities of life after communism. During her tenure, the theatre, known for its artistic experimentation and politically subversive productions, has drawn the fire of Grobelny, known for his ultraconservative views.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day has played at the Edinburgh Festival, London’s LIFT, at the universities of Yale and Princeton, as well as innumerable major and small venues in Poland. The New York Times has written on their production under the heading “When Courageous Artists Ripped Holes in the Iron Curtain“.

During last month’s Index on Censorship debate with Timothy Garton Ash, Kate Maltby and David Edgar, about freedom 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I tried to emphasise how important such new dissidents are in Eastern Europe. Commenting on this debate, Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg reminded us how authorities are taking an increasingly hard line on civil society groups.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day, which helped build an alternative civil society under communism, continues its non-conformity — and faces threats from Poznan’s political establishment. Wojciak is being unfairly dismissed for defying the far right, clericalism, the “moral majority” and censorship.

Grobelny’s record as mayor of Poznan, a job he has held since 1998, leaves much to be desired in an open, democratic society. He has repeatedly stifled independent voices in the city, and Wojciak has been a long-standing adversary. In 2005, Grobelny banned the Equality March, a feminist-queer pride event. Wojciak and other members of the Theatre of the Eighth Day took part in this forbidden event, which was suppressed by the police — one of the actors was arrested. More recently, Grobelny also supported the Poznan ban of the play Golgota Picnic, on which Index has reported.

In 2013 Wojciak was reprimanded by the mayor for a comment on her Facebook wall immediately after the conclave of Pope Francis: “[T]hey’ve elected a prick who denounced left-wing priests under the military dictatorship in Argentina.” Her Facebook account was shut down and Wojciak — mistaken about the Pope’s involvement with the Argentinian junta — was vilified by Poland’s far right. Her Facebook account was later restored and the Poznan prosecutor declined to pursue the matter. At the time, intellectuals and artists defended her on grounds of free expression.

Adam Michnik, editor-in-chief of Poland’s leading broadsheet Gazeta Wyborcza and a legendary dissident, wrote that he supports Wojciak. Michnik is a member of the committee of the fiftieth anniversary of the Theatre of the Eighth Day. A petition protesting the dismissal of Wojciak has been issued by civic-educational initiative Otwarta Akademia (“Open Academy”), spearheaded by Piotr Piotrowski, an art historian and former director of Warsaw’s National Museum (who initiated the groundbreaking exhibition Ars Homo Erotica there), feminist Izabela Kowalczyk, artist Marek Wasilewski and ethicist Roman Kubicki, among others.

This petition has so far been signed by 317 people, including Irena Grudzinska-Gross of Princeton University and Alina Cala of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, who both write on anti-semitism in Poland; Elzbieta Matynia of the New School for Social Research and author of Performative Democracy; Jeffrey C. Goldfarb, author of The Persistence of Freedom: The Sociological Implications of Polish Student Theatre; and Pawel Leszkowicz of Poznan University, curator of Ars Homo Erotica.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day epitomises liberty: Wojciak and her company speak out against injustices and experiment aesthetically. It’s deplorable that they should be repressed by the authorities of their city.

If you would like to protest the dismissal of Ewa Wojciak, please email [email protected] with the subject “Ewa”.

This article was posted on August 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Jul 2014 | About Index, Comment, News and features, Religion and Culture

Martin Roth, Kate Maltby, Sebastion Borger, David Edgar, Tomasz Kitlinski and Timothy Garton Ash.

In 1977, the Russian dissident Alexander Ginzburg — whose detention and sentencing almost a decade earlier helped to spur the creation of Index on Censorship — was again arrested by the Soviet authorities. For 17 months, a team of KGB officers interrogated the poetry publisher, threatening to arrest friends and colleagues unless he co-operated, attempting to scare him with the prospect of the death penalty and denying him medical treatment.

In the midst of this, Ginzburg recalled: At least I knew they would not kill me before the trial. “This is because I was a defended person, someone whom the West knew about and was likely to make a fuss about. Without this form of defence, political prisoners just die”.

I was reminded of Ginzburg’s comments last night as we discussed freedom in Europe 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A question was posed: Are we more free than we were in 1989? In a surprisingly tightly contested vote, the majority edged it with the decision that we were freer.

Kate Maltby, one of our panellists, pointed out that her Hungarian family could now travel freely to meet loved ones outside the country, something they could not do before the wall fell. Others on the panel, which included historian Timothy Garton Ash and playwright David Edgar, pointed to political plurality and greater protections for free expression. Martin Roth, director of the V&A museum, recalled the East Germany’s transition to capitalism in Dresden, with graffiti reading “Elect money”. But a warning note was also sounded that reminded the audience that hard won freedoms need to be protected. Tomasz Kitliński, Polish political philosopher and civic activist, put it best when he described the new dissidents: artists and writers who continue to face threats from the authorities. He pointed to cases like that of Dorota Nieznalska, who was convicted of blasphemy, fined and prevented by a judge from leaving the country for displaying a piece of art that included an image of a penis on a cross. The exhibition of which her installation formed part was closed down by authorities.

Elsewhere, as we see in the reports coming into our EU media mapping project, authorities, particularly in the Balkans, are taking an increasingly hard line on the media and other civil society groups, while in countries like Russia and Turkey new laws are being used to suppress freedom of expression online. Threats also persist offline. Last week, Index joined calls for Tajikistan to release a Canada-based academic, Alexander Sodiqov, who was arrested for “spying” while on a research trip and who now faces a jail sentence of between 12 and 20 years. Sodiqov is also accused of treason a charge that was similarly laid at the door of Ginzburg by the Soviet authorities nearly 40 years ago.

Are we more free in Europe and the former Soviet Union than in 1989? Certainly. Are we all more free? No. And, as cases like those of Sodiqov remind us, we can never be complacent.

This article was posted on July 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jun 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society

Index speaks at the IAPC meet 2014, Vienna

There has been an 18% rise in violence towards journalists compared to the same period last year, International Media Support, an organisation that works in many of the world’s biggest danger zones, told an international journalism conference.

News from Egypt – as three journalists from Al-Jazeera are sentenced to seven years in prison – demonstrates the huge threats that journalists can face. The subject was covered in detail at this year’s International Association of Press Clubs annual conference in Vienna, which Index on Censorship attended this month.

“Some countries we just can’t work in,” said John Barker from Media Legal Defence Initiative, who help represent journalists facing legal charges for reporting and presented on their work. “Every time we work in Vietnam, for example, the lawyers are arrested. In many places, we can’t transfer money to them.” Nonetheless, they are currently working on 102 cases in 39 countries.

Other topics for discussion included:

- The increasing number of freelancers working in danger zones – and with little training

- How to protect fixers, translators and local journalists

- Possible methods for funding legal representation (Crowdfunding worked as a recent experiment in Ethiopia, said MLDI)

The event was hosted by Austria’s PresseClub Concordia – said to be the oldest press club in the world (founded in 1859 – reformed in 1946, after having its assets seized by Nazis). It was attended by press clubs from around the world, including Poland, Belarus, Syria, the Czech Republic, the US, India, Ukraine, Mongolia, Germany, and Switzerland. Other NGOs – alongside Index, International Media Support and Media Legal Defence Initiative – included the International Press Institute and RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues).

Index was invited to present on the work the organisation is doing around the world, which included sharing the stories of our Freedom of Expression Awards winners and nominees, and news of our current work, including a crowdsourcing project to map media freedom violations across the EU. Plus we also shared stories from our quarterly magazine – including a report on violent threats to journalists in Tanzania and how news stories are getting out of Syria via citizen reports.

Index also hosted round-table discussion on censorship, which provoked an impassioned debate. One of the most interesting topics covered was on contracts that some journalists are being made to sign on what they can and can’t write. We heard of cases in Mongolia and Germany. We also discussed self-censorship and censorship by complying to advertisers’ will. One attendee from the Berlin Press Club said: “There is no censorship in Germany, but journalists feel like they have scissors in their heads. You have to self-censor before you write.” This is an area that we are researching, so please get in touch if you have experiences and examples.

The meeting also visited a new exhibition on censorship during WW1 and ended with the Concordia Press Club’s annual ball, which is a key fundraiser for the club and attended by over 2,000 guests. See photos from the event below.

This article was posted on June 24, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

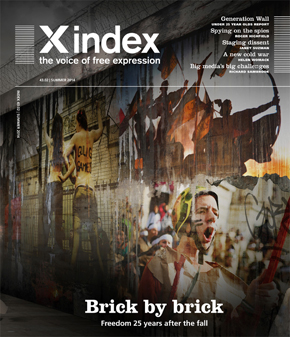

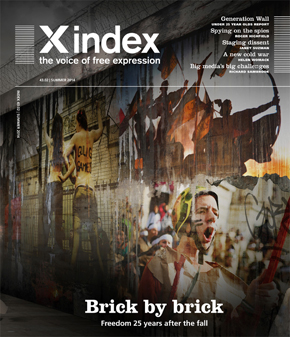

13 Jun 2014 | Events, Magazine, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

In 1989, the border separating eastern and western Europe opened as communism collapsed. Twenty-five years after the event that came to symbolise the end of the Cold war, our latest magazine explores how the continent has changed. Are any of us truly freer now than we were then?

Join us for a summer drinks reception on the beautiful terrace of the Goethe Institut and a lively Question Time-style discussion, chaired by editor of Index on Censorship magazine Rachael Jolley.

Featuring:

• David Edgar, playwright

• Timothy Garton Ash, historian, author of The Magic Lantern and The File

• Martin Roth, director of the V&A, former director Dresden State Art Collections

• Polish philosopher and LGBT activist Tomasz Kitlinski

• Kate Maltby, editor Bright Blue Magazine and journalist

• Sebastian Borger, German author and journalist

When: Thursday 10th July, 6:00 reception, 6.30-7.30pm event, drinks after

Where: Goethe Institut, Exhibition Road, London, SW7 2PH (Map/directions)

Tickets: Free, registration is required as space is limited.

@IndexEvents – #AfterTheWall

BRICK BY BRICK launches the summer edition of the Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine for one issue or for the entire year and in print, online or by app.

Presented in partnership with

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.

Flourishing, inclusive and just – or blisteringly unequal, subtly repressive and endemically corrupt? Debating freedom 25 years after the fall.