3 May 2017 | About Index, Digital Freedom

- Introduction

1.1 We are committed to safeguarding the privacy of visitors to www.indexoncensorship.org; we strive to minimise the amount of information we collect or allow to be collected by third parties on our website; in this policy, we explain how we will treat your personal information.

1.2 We will ask you to consent to our use of cookies in accordance with the terms of this policy when you first visit our website. By using our website and agreeing to this policy, you consent to our use of cookies in accordance with the terms of this policy.

- Collecting personal information

2.1 Where possible we minimise the amount of information we collect by contracting with third parties. For example, event ticketing through Eventbrite (Privacy Policy) or donations processing through PayPal (Privacy Policy)

2.2 We may collect, store and use the following kinds of personal information:

(a) information about your computer and about your visits to and use of this website including your IP address, geographical location, browser type and version, operating system, referral source, length of visit, page views and website navigation paths

(b) Information that you provide to us for the purpose of subscribing to our email notifications and/or newsletter including your name and email address

(f) Information contained in or relating to any communication that you send to us or send through our website including the communication content and metadata associated with the communication

(g) Any other personal information that you choose to send to us; and provide details of other personal information collected.

2.3 Before you disclose to us the personal information of another person, you must obtain that person’s consent to both the disclosure and the processing of that personal information in accordance with this policy.

- Using personal information

3.1 Personal information submitted to us through our website will be used for the purposes specified in this policy. Your information will not be published without your explicit permission.

3.2 We may use your personal information to:

(a) Administer our website and business

(b) Enable your use of the services available on our website

(c) Send you email notifications that you have specifically requested

(d) Send you our email newsletter, if you have requested it; You can inform us at any time if you no longer want to receive the newsletter

(e) Send you marketing communications relating to our business, where you have specifically agreed to this, by email, text or similar technology you can inform us at any time if you no longer require marketing communications

(f) Deal with enquiries and complaints made by you relating to our website

(g) Keep our website secure and prevent fraud

(h) Other uses

3.3 If you submit personal information for publication on our website, we will publish and otherwise use that information in accordance with the licence you grant to us.

3.5 We will not supply your personal information to any third party for the purpose of their or any other third party’s direct marketing.

- Disclosing personal information

4.1 We may disclose your personal information to any of our employees, officers, insurers, professional advisers, agents, suppliers or subcontractors insofar as reasonably necessary for the purposes set out in this policy.

4.3 We may disclose your personal information:

(a) To the extent that we are required to do so by law;

4.4 Except as provided in this policy, we will not provide your personal information to third parties.

- International data transfers

5.1 Information that we collect may be stored and processed in and transferred between any of the countries in which we operate in order to enable us to use the information in accordance with this policy.

5.2 Information that we collect may be transferred to the following countries which do not have data protection laws equivalent to those in force in the European Economic Area: the United States of America

5.3 Personal information that you publish on our website or submit for publication on our website may be available, via the internet, around the world. We cannot prevent the use or misuse of such information by others.

5.4 You expressly agree to the transfers of personal information described in this Section 5.

- Retaining personal information

6.1 This Section 6 sets out our data retention policies and procedure, which are designed to help ensure that we comply with our legal obligations in relation to the retention and deletion of personal information.

6.2 Personal information that we process for any purpose or purposes shall not be kept for longer than is necessary for that purpose or those purposes.

6.3 Notwithstanding the other provisions of this Section 6, we will retain documents (including electronic documents) containing personal data:

(a) To the extent that we are required to do so by law;

(b) If we believe that the documents may be relevant to any ongoing or prospective legal proceedings; and

(c) In order to establish, exercise or defend our legal rights (including providing information to others for the purposes of fraud prevention and reducing credit risk).

- Security of personal information

7.1 We will take reasonable technical and organisational precautions to prevent the loss, misuse or alteration of your personal information.

7.2 We will store all the personal information you provide on our secure password- and firewall-protected servers.

7.3 All electronic financial transactions entered into through our website will be protected by encryption technology.

7.4 You acknowledge that the transmission of information over the internet is inherently insecure, and we cannot guarantee the security of data sent over the internet.

- Amendments

8.1 We may update this policy from time to time by publishing a new version on our website.

8.2 You should check this page occasionally to ensure you are happy with any changes to this policy.

8.3 We may notify you of changes to this policy by email

- Your rights

9.1 You may instruct us to provide you with any personal information we hold about you; provision of such information will be subject to:

(a) The supply of appropriate evidence of your identity for this purpose, we will usually accept a photocopy of your passport certified by a solicitor or bank plus an original copy of a utility bill showing your current address.

9.2 We may withhold personal information that you request to the extent permitted by law.

9.3 You may instruct us at any time not to process your personal information for marketing purposes.

9.4 In practice, you will usually either expressly agree in advance to our use of your personal information for marketing purposes, or we will provide you with an opportunity to opt out of the use of your personal information for marketing purposes.

- Third party websites

10.1 Our website includes hyperlinks to, and details of, third party websites.

10.2 We have no control over, and are not responsible for, the privacy policies and practices of third parties.

- Updating information

11.1 Please let us know if the personal information that we hold about you needs to be corrected or updated.

- About cookies

12.1 A cookie is a file containing an identifier a string of letters and numbers that is sent by a web server to a web browser and is stored by the browser. The identifier is then sent back to the server each time the browser requests a page from the server.

12.2 Cookies may be either “persistent” cookies or “session” cookies: a persistent cookie will be stored by a web browser and will remain valid until its set expiry date, unless deleted by the user before the expiry date; a session cookie, on the other hand, will expire at the end of the user session, when the web browser is closed.

12.3 Cookies do not typically contain any information that personally identifies a user, but personal information that we store about you may be linked to the information stored in and obtained from cookies.

12.4 Cookies can be used by web servers to identify and track users as they navigate different pages on a website and identify users returning to a website.

- Our cookies

13.1 We use both session and persistent cookies on our website.

13.2 The names of the cookies that we use on our website, and the purposes for which they are used, are set out below:

(a) We use cookies on our website to recognise a computer when a user visits the website, track users as they navigate the website, improve the website’s usability, analyse the use of the website, administer the website, prevent fraud and improve the security of the website.

(b) Third parties may track users on our website when they interact with specific site functions such as social media sharing buttons or embedded video.

- Analytics cookies

14.1 We use Google Analytics to analyse the use of our website.

14.2 Our analytics service provider generates statistical and other information about website use by means of cookies.

14.3 The information generated relating to our website is used to create reports about the use of our website.

14.5 Our analytics service provider’s privacy policy is available at: http://www.google.com/policies/privacy.

- Blocking cookies

16.1 Most browsers allow you to refuse to accept cookies; for example:

(a) in Internet Explorer you can block cookies using the cookie handling override settings available by clicking “Tools”, “Internet Options”, “Privacy” and then “Advanced”;

(b) in Firefox you can block all cookies by clicking “Tools”, “Options”, “Privacy”, selecting “Use custom settings for history” from the dropdown menu, and unticking “Accept cookies from sites”; and

(c) in Chrome, you can block all cookies by accessing the “Customise and control” menu, and clicking “Settings”, “Show advanced settings” and “Content settings”, and then selecting “Block sites from setting any data” under the “Cookies” heading.

16.2 Blocking all cookies will have a negative impact upon the usability of many websites.

16.3 If you block cookies, you will not be able to use all the features on our website.

- Deleting cookies

17.1 You can delete cookies already stored on your computer; for example:

(a) In Internet Explorer, you must manually delete cookie files you can find instructions for doing so at http://windows.microsoft.com/engb/internet-explorer/delete-manage-cookies#ie=ie-11;

(b) in Firefox you can delete cookies by clicking “Tools”, “Options” and “Privacy”, then selecting “Use custom settings for history” from the drop-down menu, clicking “Show Cookies”, and then clicking “Remove All Cookies”; and

(c) in Chrome, you can delete all cookies by accessing the “Customise and control” menu, and clicking “Settings”, “Show advanced settings” and “Clear browsing data”, and then selecting “Cookies and other site and plug-in data” before clicking “Clear browsing data”.

17.2 Deleting cookies will have a negative impact on the usability of many websites.

- Our details

18.1 This website is owned and operated by Index on Censorship (Writers & Scholars Education Trust Ltd.)

18.2 Writers & Scholars Educational Trust is a registered charity (number 325003). Our office is located at 292 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 1AE. If you have any other questions about this policy you can write to us at our office or email [email protected] or call us on +44 (0) 207 963 7262

3 May 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

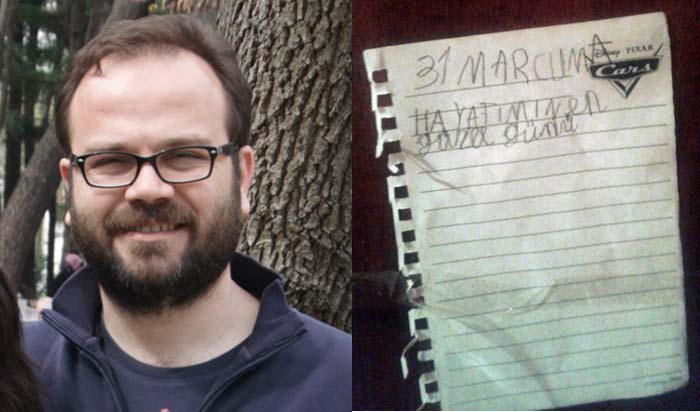

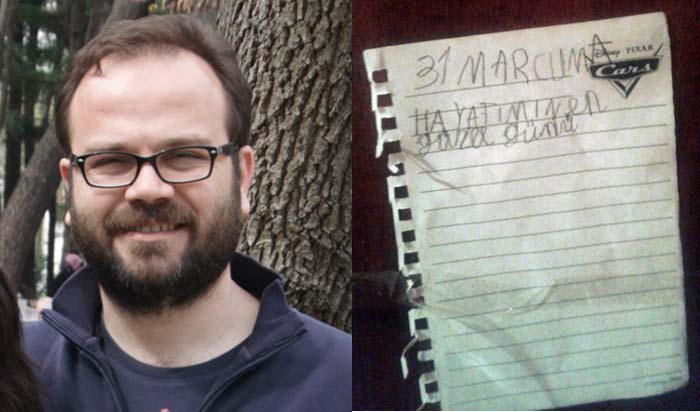

Journalist Oguz Usluer has been accused of being a terrorist. The note, from his six-year-old son, reads: “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.”

On 31 March 21 journalists who were charged with working for the media arm of the alleged group behind the 15 July coup attempt were released by a court ruling. Following a tweet from a pro-government troll account, the prosecutor filed an objection to the release of eight and announced that it had launched a new investigation for the other 13.

The judges who issued the release ruling were suspended about a week after the trial.

During the few hours before the new detention warrants came, their families had already driven to Silivri Prison, where they have been held for months. Among them was Sunay Usluer, the wife of a former television coordinator who was arrested in December 2016. She shared with Index on Censorship her account of the anxious hours waiting for the release that never came.

“I am planning to bring the children to the next visit after the trial.”

“But of course there is always the possibility that I might be released in the next session, although you seem not to even consider that.”

Such was the conversation I had with my husband Oğuz on Thursday 23 March, during my last prison visit before the 31 March trial hearing. This entire process had the air of a tragicomical joke; we were laughing when we should have been crying. Although for the past four months, neither of us had given up hope, we didn’t really expect a fair trial or a release ruling from the court. But, at least, we would be able to see each other for five days in a row during the scheduled trial sessions; a rare occurrence.

With this motivation, we started the five-day session marathon. The 25 people, who were on trial for membership in a terrorist organisation and who didn’t know each other in the slightest, were in the front row in the courtroom. Dozens of their family members, living 25 different human stories together with them, sat in the back of the room. Everyone wore the same exhausted expression on their face, reflecting the months fraught with ambiguity and fragile flickers of hope.

While waiting for the trial sessions that never seemed to start, or while waiting during long intervals, people who put their own identities aside and described themselves as the “wife, mother, son/daughter” of a particular journalist, started speaking about the shared-yet-separately-lived agony they have endured, after months of longing for a conversation with someone who can understand them. One of them said, “I can’t tell you how happy I am to see that people who are going through the same tribulations as me still being able to laugh,” while we laughed as we played a game of release-lotto with our lawyer.

Our lawyer has been extremely supportive in this process. He always had hope, but I was the devil’s advocate. “You say he will be released, but I will not believe that until I see him next to me.”

Court officials moved the trial to a smaller courtroom for the final three days. Family members of those on trial were allowed inside only for 15 minutes in whatever room was left unoccupied by journalists and lawyers.

On the morning of the fifth and final day, the prosecutor was reading out a list of those he recommended be released. At that moment, I caught Oğuz’s eye and made a gesture asking if he was on the list. “Yes, but it’s only the prosecutor’s request,” he said, in order to fend off the likely frustration that might follow. Fearing to have hope is worse than despair; something we have found out in this process.

At the end of the fifth day, everyone was too exhausted to even speak. While waiting for the court’s decision, only the sounds of shy seagulls from outside could be heard as if it was sinful to talk in the corridor where the 25th High Criminal Court is located. Then there was the sound of a notification on my phone, and the ticker reading “released” on a television screen. This scene was followed by 21 families, crying tears of happiness, hugging each other. People who still found the news hard to believe, relying on confirmations from each other.

“I couldn’t believe it. I walked towards the courtroom, and I asked a lawyer who I didn’t know at all if my husband is among those released. I suddenly gave him a hug when he answered yes,” somebody said.

Later, our lawyer walked out of the courtroom. His first remark took a jab at my longstanding incredulity. I still had no intention of believing that he really was to be released until he was next to me. I didn’t voice my concern in the way you think you might jinx a good thing if you say something negative. I, carrying this worry in my heart, my ten-year-old son, whom I’d brought with me so that he could at least catch a glimpse of his father, and our relatives celebrated. Oğuz’s family in İzmir were already boarding a plane to Istanbul to celebrate with us. We will most likely have picked him up from prison by the time they arrive, I thought.

We left the courthouse with a sense of joy and began driving to Silivri. Even the distance, which has become complete torture for us as we have to travel every week, felt short. Families were already waiting outside the main gate of the Silivri Prison in the anticipation of seeing their husbands, fathers and brothers again. Everyone was smiling now, carrying on conversations filled with hope despite the biting cold. One family had brought a celebratory band of drummers from Edirne, who were going to play as their relative was released. Everyone’s eyes were fixed on the main gate.

The first few hours were just like a carnival.

Then the mood changed. The crowd started to feel that something was off, but no one had the courage to speak it. In the middle of the night, vehicles that didn’t have official license plates entered the prison one after another, and all of them drove towards Section 9. Later, they set up a barricade to block the view of the parking lot that faced the main gate. A police van entered the prison. Could it be that they had brought them to the prison from the courthouse just now? At some point, armoured vehicles of the gendarmerie special operations command arrived. Wasn’t this much security a bit extreme for a handful of people?

The air of festival had left the crowd, and it had gotten much colder. Still, nobody could bring themselves to speak the fear they held. Many of them started waiting in their cars, saying it was too cold. As I waited inside the car, a friend texted me, telling me to be cautious and sent a tweet posted by some creature:

“We will take’em if you release’em,” it said.

At that moment, in the middle of the night in the Silivri cold, in what was possibly the most secure part of my country, among the gendarmerie and police officers, I feared for the life of the children playing between the parked cars despite the cold air and for the life of my own son.

Dr. Sunay Usluer and her ten-year-old son waited outside the dates of the prison for a release that never came.

What came after was a long and desperate wait; a semblance of hellish torture. All of a sudden, they forbid us to wait near the prison because of the state of emergency, and we were ordered to drive towards the highway slip road; they said those released would be brought there. In that moment, somebody worked up the courage to ask: “Is there a problem?”

“There is no problem Miss, the release procedures are being conducted inside. It’s just taking a bit of time because there are many people. Continue to wait in the area ahead.”

But that “area ahead” kept moving forward. People were constantly driven away further and further from the prison, and finally, they ended up waiting at a spot from where the slip road was invisible. At the entrance to the highway, there was a gendarmerie vehicle, guarded by two privates. Every time we asked them what was going on, they could only tell us: “We can only give you information when our commanders give us information.” At the same time, we kept checking our Twitter feeds. At this point, it became clear that no one would be released tonight, but none in the crowd could drop the slightest flicker of hope and leave, so we waited on and on and on.

There were small children and older people among those waiting. At some point, the vehicles started to leave one by one, eventually, maybe ten or fifteen vehicles remained. My son and I also gave up hope and decided to go home. But as we stopped to ask the gendarmerie private if there had been any developments one last time, we saw a police van in the distance.

We got back into the car and started driving towards the van. As we passed, we caught the attention of a dark silhouette inside the vehicle, who had leant his head against the window. When he saw us in the car, a flash of joy went through his body, he cocked his head and waved at us. It was him: a tiny miracle gave us the information that our supreme state had denied us. Oğuz had been detained again and he was being driven back to Istanbul, to the police department. The police van slowed down for us to pass it. We wanted to drive near again and take a better look, but this time plainclothes officers drove us away.

The hardest part in all of this is to try and maintain one’s composure in front of the children. My son and I lived this experience as if we were having a good time; as if we were in an adventure movie. Neither of us cried. But when we reached home in the early morning hours, we were met with a note by my six-year-old son, who is just learning to write, on the door. “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.” His brother and I sat down on the stairs of our building, held each other and burst into tears. How were we to explain to him why his father hadn’t come home?

This was how I saw my husband 15 days ago. After that, he and his co-defendants were kept for in detention seven days at the police station on Vatan Street in Istanbul, which was extended for another seven days. During this time, they sent us his belongings from Silivri Prison; his notes, summaries of books he wrote down. For the past months, he wasn’t allowed to send mail.

I was exhilarated as if I had gotten a pages-long letter; I even read the receipts he had kept from the prison cafeteria. There was also a to-do-list, where he wrote down what he planned to do after his release. The first item on his list was, “Don’t forget about those who remain in prison, and don’t let them be forgotten.” At the end of the day, he is a journalist.

The process that followed was the same as before, police interrogation, another desperate wait at the Çağlayan courthouse during the prosecutor’s questioning and court interrogation, again “what if”; once again disillusionment and ambiguity. What happened to the previous panel of judges only shows the extent of independence of our judiciary and sets the maximum for our expectations.

At the end, they were rearrested on new charges, a decision that didn’t really surprise us. All we could do was say, at least they are back in Silivri Prison, back to their routine, sleeping in a normal bed [as opposed to detention conditions]. I woke up on Saturday and called the prison to find out if they had moved him to a different cell. “Nobody was brought here last night,” the voice at the end of the line said.

I later found out that the police, which drove back to Silivri in a convoy without wasting a second to re-arrest them on the night of 1 April — were simply too lazy to drive back to Silivri on 16 April and they dumped my husband — my partner of 12 years, the father of my children, a yeoman journalist who dedicated 20 years to reporting the news — at Metris Prison [in central İstanbul] like some piece of baggage dropped at storage for safe keeping.

Period.

Dr. Sunay Usluer

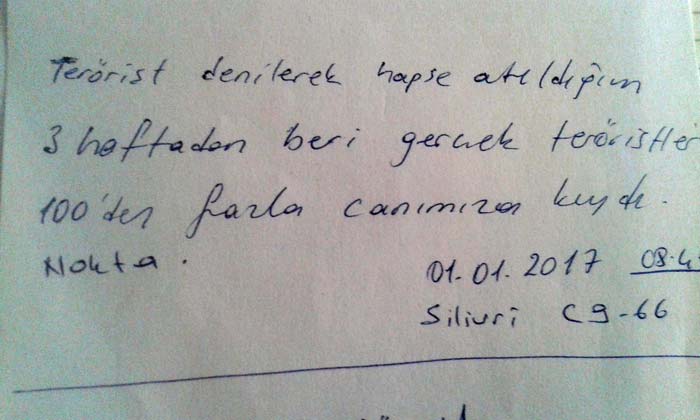

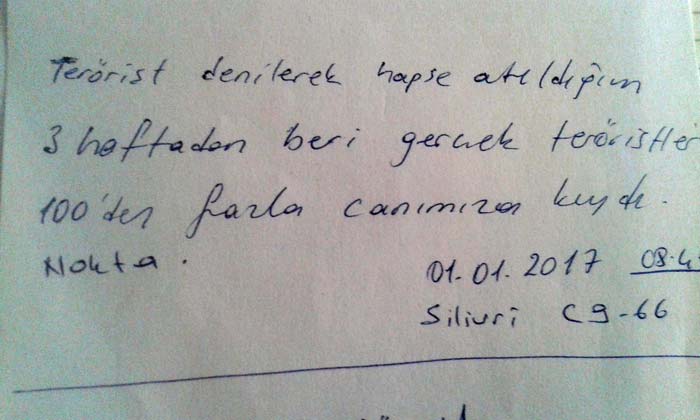

“In the past three weeks, during which I have been imprisoned being declared a terrorist, real terrorists have taken away 100 lives from us.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493981743376-3f86911a-75c7-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Apr 2017 | Asia and Pacific, Awards, Digital Freedom, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News and features, Pakistan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

It has been eight months since the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), also known as the cyber crimes bill, was passed and enacted in Pakistan. The law, which has been in place since August 2016, is meant to limit the amount of hate speech online and protect internet users against malicious cyber crimes, however, many are concerned that it has not followed up on these promises.

Bolo Bhi, a non-profit organisation and activist group and winners of the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning, has been vehemently opposed to PECA from the beginning because of its potential human rights violations and threats to the right to privacy and freedom of expression as the law would allow more unchecked government power and internet regulation.

Farieha Aziz, the director of Bolo Bhi, told Index on Censorship that there are simply not enough rules, oversight, and public awareness for the law to truly be effective in preventing cyber crime.

“If the government was really serious about the implementation of the law for the protection of the people, eight months on, where are the rules? Courts? Capacity of the Federal Investigation Agency, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, prosecutors and courts to deal with cases?” Aziz said. “Why the deafening silence on this both the government and the opposition?”

Aziz said that government critics and other dissenters have been silenced as a result of the law, but the government has yet to make any effective moves against real malicious threats. She noted that the Khabaristan Times, a satirical media organisation, was recently blocked online under Section 38 of PECA which allows the government to remove and censor any “objectionable content”.

“This essentially stems from a failure to still grasp how the internet and technology function, and where and how the law can or cannot be applied,” Aziz said.

Bolo Bhi has published a document on its website titled “Recommendations for Implementation and Oversight” to solve the numerous problems regarding effective and fair enforcement of PECA.

One of the main problems, Bolo Bhi noted, is confusion and lack of clarity among the public of PECA’s rules and regulations.

“Social perceptions of what constitutes stalking, harassment, bullying, etc. and the legal definitions of these as well as what constitutes a crime under law can be very different,” Bolo Bhi said in the document.

In order to combat this, Bolo Bhi recommended increasing public awareness through various resources including public service messages and helpline numbers. Bolo Bhi also suggested the creation of an online complaint facility and a more transparent case management and tracking system that would be available to the public.

Another problem with effective enforcement of PECA includes a lack of financial resources and qualified professionals for online surveillance and responding to cases.

The PTA, one of the most prominent government agencies involved with the implementation of PECA, told the Senate Standing Committee on Information Technology on the 5th of April that they do not have enough resources to properly manage and surveil all online content. Instead, the PTA suggested, the government should build closer relationships with social media websites such as Facebook and Twitter to help find and block and unacceptable or blasphemous content.

Bolo Bhi, however, suggested that the government itself should be held responsible for increasing the amount of trained investigation officers and state prosecutors who can properly handle an increasing caseload. If there is more legal and technical training for judicial officers, Bolo Bhi said, then cyber crimes can be dealt with more quickly and efficiently. Bolo Bhi also recommended increasing the number of third-party forensic labs in order to avoid further backlogging of cases.

Despite PECA’s lack of progress in creating a safe and sustainable internet for Pakistan, Bolo Bhi continues to fight on for fair and effective implementation of the Cybercrimes law.

“The law alone is no solution,” Bolo Bhi said. “Awareness of its existence, knowledge of the procedures, willingness to use it and them proper implementation for deliverance of justice that is tied with our criminal justice system and courts are all components of this, which need to be addressed simultaneously.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492103286683-011373cf-290a-6″ taxonomies=”8093″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Apr 2017 | News and features, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” full_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1491319101960{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Cover-slider.jpg?id=88947) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The “now” generation’s thirst for instant news is squeezing out good journalism.

We need an attitude change to secure its survival” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

THIS WORLD HAS never been in more need of good, well-researched journalism. It is tempting to write the words “old-fashioned” here too. And if by old-fashioned, what is meant is detailed, neutral, in-depth and well thought-out writing, then old-fashioned is what is called for.

Around the world there are squeezes from all directions, stifling what the public is allowed to know, and what it is allowed to say or write. From government pressure to mafia threats, from commercial agencies to reputation- damaging (ro)bots, the right to speak and report is under huge pressure.

And good journalism must be there to unmask those threats. With the rise of the words “fake news” comes a spirit that seems to think that I can apply this phrase to anything I disagree with. So the epithet “fake news” was out of its box and being used to try to disarm reporters and to undermine public belief both in research, experts, truth and often journalism.

So, this is a time for journalists and journalism to step up and do a really excellent, thorough job of discovering and publishing the news: that’s not a news broadcast or publication that is just a hodgepodge of opinions based on very little research; nor a news story that has so much spin in it it’s hard to discern any actual facts. There are those that might argue that the media has been through a pretty unimpressive period in the past 10 years, with some valiant exceptions. The line between the news and opinion pages has become increasingly hard to distinguish. So, it might be less than surprising that the public might have lost faith in news sources.

Social media has played a massive part in this. Hysterical opinion goes down a storm, instantly shared across platforms; while well-argued journalism, with more facts than screeching, tends to stay in its box, unread. And, of course, there are signs that attention spans are melting away. So not only does every item have to be now, now, now, but we can only be bothered to read the first line, or look at the picture.

Sadly, research from Stanford University shows young people are gathering their “news” from social media without bothering even to click through on a link. They also have trouble discerning the difference between a social media-placed advertising feature and a news story from a well-established news media company. So shareable opinion has become king, and news has melted away and merged into a hybrid of what it once was.

But journalists need to take back the news wherever they can, and re-establish it as a well-researched, investigated piece of information, not an outpouring of ill-informed thoughts. And the public has to take some responsibility too. We need to be capable of a bit more dissection and scepticism when we see stories, rather than swallowing them whole without thinking.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Hysterical opinion goes down a

storm, instantly shared across

platforms; while well-argued

journalism, with more facts

than screeching, tends to stay in

its box, unread” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As our seasoned journalists explain in our Decoding the News special, everyone should be aware of techniques and tools to stop them being taken in, at least most of the time. Meanwhile, journalists are doing some really strong investigations.

As we go to press the BBC was broadcasting a story about truck drivers in the supply chain for furniture company Ikea, who were being paid less than the minimum wage, and being forced to live in their vehicles. They were drivers from Romania but working in Denmark, where they should have been paid according to Danish laws. The journalist was on the road talking to lorry drivers to find the story. Stories like these are hard to dispute, because the journalist has evidence to stand up the allegations.

Over in the Maldives, journalist Zaheena Rasheed, shortlisted for an Index journalism award this year (see page 37), is reporting about what is happening in the south Asian island country, despite a climate of fear. And in other countries, remarkable reporters continue to make extraordinary efforts to get news out, despite dangerous conditions.

There are some signs that the world is starting to realise it needs good journalism. The New York Times saw a growth of 41,000 subscriptions in the week immediately after the election of President Trump. Sales of satire and news magazine Private Eye recently hit their highest level ever with 287,334 copies sold for one issue. Reports from Poland suggest a surge in sales of independent weekly Tygodnik Powszechny (see our report on page 69). This in a country that is seeing its media freedom fall down global charts. Jeremy Leslie, creative director of magazine- only shop Magculture in London, said he is seeing an upward tick in the sales of magazines “with serious intent”.

“More people are making [magazines with that type of content] and more people are buying it,” he told Index on Censorship.

Is this a sign that some members of the public are learning at last that if they want journalism that tells them something they don’t know (and isn’t made up), they just might have to pay for it? Only time will tell. Otherwise, the survival of journalism looks fraught with danger.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine. She recently won the editor of the year (special interest) at British Society of Magazine Editors’ 2016 awards

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80566″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422015605737″][vc_custom_heading text=”A matter of facts: fact-checking’s rise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422015605737|||”][vc_column_text]September 2015

Vicky Baker looks at the rise of fact-checking organisations being used to combat misinformation, from the UK to Argentina and South Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80569″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422016657017″][vc_custom_heading text=”Giving up on the graft and the grind” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422016657017|||”][vc_column_text]June 2016

European journalist Jean-Paul Marthoz argues that journalists are failing to investigate the detailed, difficult stories, fearing for their careers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90839″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/030642209702600315″][vc_custom_heading text=”In quest of journalism” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F030642209702600315|||”][vc_column_text]May 1997

Jay Rosen looks at public journalism, asserting that the journalist’s duty is to serve the community and not following professional codes.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fmagazine|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88788″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]