1 Mar 2011 | Middle East and North Africa, News and features

“Listening to the fear in people’s voices had been heartbreaking but not hearing anything was terrifying,” describes Huda Abuzeid, Libyan exile and filmmaker

Nobody expected Libya’s protests to amount to much; after 42 years everyone had all but given up on the country.

Nobody expected Libya’s protests to amount to much; after 42 years everyone had all but given up on the country.

Even when 17 February was touted as Libya’s day of rage, pretty much everyone believed protest would be quashed, quickly and bloodily.

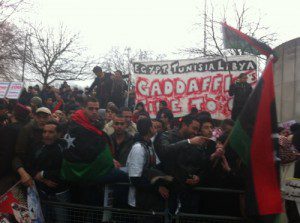

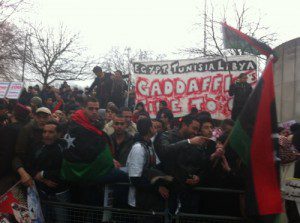

On 15 February, Fathi Terbli, a human rights lawyer acting on behalf of the families of the Abu Salim prison massacre was arrested in Benghazi, Libya’s second city on the eastern border with Egypt. [Photo, right: via Twitpic, protests outside the Libyan embassy in London].

Worried about recent events in Tunisia and Egypt either side of Libya, the authorities had decided on a pre-emptive strike to try and prevent any possible protests before they started.

Arrests and disappearances were the regime’s favourite way of instilling fear, a method that had kept the populace cowed for over four decades.

This time, however, the arrests actually brought the protests out a day early. Benghazi’s people surrounded the police station where Terbli was detained, refusing to move despite clashes with security forces, and he was soon released.

This first win, inspired by Tunisia and Egypt, spread throughout the east and many western areas, leaving Gaddafi ruthlessly fighting from his remaining stronghold in Tripoli.

Exiled voices

As this was happening I, along with every other Libyan exile, tried to figure out how to help. What could we possibly do from abroad to support the incredible people who were braving snipers, mercenaries and heavy fire to overthrow the Gaddafi regime city by city?

The one thing Gaddafi has been successful at is cutting off Libya from the world. Whilst he was welcomed back into the international community with unseemly haste in 2003, his own people were still not to be seen or heard of without fear of reprisals.

Those who spoke would be quickly silenced, even those safely abroad were warned that their relatives inside the country would be targets if they publicly criticised the newly “reformed” regime. Damned if you spoke, damned if you didn’t.

Limited media

The international media was wrong footed, suddenly trying to cover a country about which little was known, and where they had no journalists or cameras to independently report what was happening.

During the first few days of Libyan protest there was barely any news coming out; the mobile phone clips that would appear online were short and so badly shot that it was difficult to make out what was happening.

The phrases “citizen journalism” and “user generated content” have become popular in the past few years, but when these forms of media were the only news source their limitations became apparent.

The fact that this was a genuinely popular uprising also meant that the go-to Libyan figures abroad didn’t know who was responsible either, so they themselves were struggling to follow events.

As a TV producer I knew that international media coverage was key to breaking through Gaddafi’s wall of silence. Not only would it ensure the world saw what was happening, but more importantly, that news reached those inside Libya watching Al-Jazeera, BBC Arabic and other channels, with the truth about what was happening in other parts of the country.

Libyans abroad could offer the media their perspective from any town or city across Libya, challenging the notion of different tribes who would be unable to unite once Gaddafi went.

Everyone had willing relatives desperate for someone to hear their plight.

We collected numbers and phoned people on the ground, dispassionately questioned them to find out accounts of what was going on and then forwarded on the information to interested media.

When it worked we preferred Skype because it felt more secure than the heavily tapped phone lines. We translated the Libyan dialect being broadcast on a revolutionary radio station in Benghazi and concentrated on feeding the ever-hungry news channels.

Each city that fell to anti-Gaddafi forces emboldened others and as events changed hourly it was of vital importance that networks covered it.

Sadly, in the beginning it was an uphill struggle to get news networks interested. Despite knowing that phone calls from abroad were monitored, many courageous Libyans spoke directly to TV news channels. It took a couple of arrests for the media to stop using their full names. This was not Tunisia or Egypt; this was a regime that had no problem using its full power to keep its people silent.

This was practical tangible work that kept me mentally distracted, until last Tuesday when not one of our compiled telephone numbers worked. Entire cities in Libya were cut off once more from the world.

That was the first day I actually felt a sense of real panic, listening to lines go dead or just ring off. I imagined all manner of horrors being committed. Listening to the fear in people’s voices had been heartbreaking but not hearing anything was terrifying.

It was only when the lines returned and we started to help journalists get into Libya with their satellite phones that the panic began to ease.

The next mission is to collate all that citizen journalism. When no journalist was able to go in, it was the Libyan people who risked their lives to show the world the protests and attacks.

Whilst the regime blithely claimed nobody was injured, the quantity of juddering mobile phone footage of dead bodies exposed the lie. The professionals could no longer ignore the veracity of the uploaded material. Ahum Ahum al libyoun ahum “here we are, the Libyans we are here”.

Huda Abuzeid is a filmmaker and TV producer based in the UK. Follow her on Twitter: @hudduh

22 Feb 2011 | Events, United Kingdom

Index on Censorship Free Expression Award 2010 winners

The 11th annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards honour those who, often at great personal risk, have given voice to issues and stories from around the globe that would otherwise have passed unnoticed.

This year’s event will be hosted by Jonathan Dimbleby at the Royal Institution in Mayfair on 24 March. It promises to be a truly inspiring evening, with a keynote address from Booker prize-winning novelist Howard Jacobson and a special address from celebrated playwright Sir Tom Stoppard.

Over four decades Index has worked for victims of oppression and censorship, championing their right to free expression. In December, when Natalia Koliada of the world-renowned Belarus Free Theatre was arrested and bundled into a police van, her first call for help on a smuggled mobile phone was to Index on Censorship. In Tunisia we’ve been working on the ground with civil society activists for five years. In addition to our international work, we lead the campaign to reform English libel law.

The awards, kindly sponsored by SAGE, gives you the opportunity to support our vital work. We expect over 300 prominent guests this year, and your attendance will fund our ongoing campaign for free expression in the UK and abroad. The event will begin at 7pm with a champagne reception and grand canapés. After the awards ceremony we will ask you to bid high in our celebrated auction.

Help us aid the courageous efforts of people who campaign for freedom of expression even in the most hostile environments by purchasing tickets below. Each ticket comes with a FREE SUBSCRIPTION to Index on Censorship’s award-winning magazine!

You can read about last year’s Index Award winners here