Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Shanghai, a normally buzzing, dynamic city of 25 million, is in week three of an intense lockdown as part of President Xi Jinping’s desire to keep the country “Covid-Zero”. It’s buckling at the knees, so much so that they’ve had to ease measures in some areas. The desperation is in large part due to how mismanaged the lockdown has been. Shanghai authorities’ promises of providing necessities to those confined in their homes have not been kept, leaving many residents starving.

“Pets beaten to death. Parents forced to separate from their children. Elderly folks unable to access medical care. Locked-up residents chanting ‘we want to eat’ and ‘we want freedom’,” ran the lead in a Bloomberg article last week.

As anger bubbles over, the censors are working overtime.

The phrase “buying vegetables in Shanghai”, a video showing mountains of food waste, a post written by Ho Ching, wife of the prime minister of Singapore, calling the Shanghai lockdown “a waste of time, money, resources and opportunities” are just three examples of content that has been censored in the past few weeks in China.

“I am not particularly concerned about politics, and I believe many other ordinary people are the same. Most people just want a safe and comfortable land to live in.” The words of another netizen whose post was blocked. These words speak volumes. Shanghai residents’ desire to post, and particularly post under popular hashtags, isn’t necessarily about making a grand political statement. It’s about a sense of unity at a moment of desperation. It’s a cry for help. It’s a way to pool resources and offer tips.

The intense lockdown, and the government’s response to criticism of it, is deeply disturbing. At the same time it follows a depressingly familiar pattern. Beijing has been pursuing a draconian Covid control policy from the start and censorship has been the government’s bedfellow. Remember Li Wenliang, the Covid doctor who was hunted down for blowing the whistle on the virus?

The censorship we are seeing fits perfectly into the Chinese model that only allows for minimal criticism of policy from the top. And the posts, while not always directly pointed at senior leaders, clash with what they fear the most – collective action. As outlined in 2012 by a Harvard study of Chinese censorship any posts with a hint of collective intent are targeted. One example in this study came from Zhejiang Province. There, following the Japanese earthquake and the subsequent meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear plant, a rumour spread that iodine in salt would counteract radiation exposure. To offset a hectic dash to buy salt, all online content was removed. Yesterday’s iodine in salt is today’s vegetables in Shanghai.

Many are now too scared to speak online about their situation in case they get the dreaded knock on the door. They know the internet police are watching. Some have made the brave move to switch on a VPN, even though VPNs are banned in China. They really want to know exactly what is happening in their city, outside of their own four walls. Who can blame them? By this stage it’s confusing to even know what is happening in Shanghai on a purely clinical level because we simply can’t trust the numbers. Just how many people are currently ill? How effective is the Chinese vaccine against Omicron, and other variants for that matter? The official line says vaccine uptake among the most vulnerable has been low. Exactly how low?

Without knowledge of the real stats, it’s hard to see justification for the lockdown and harder still justification for such an extreme one. As for the blocking of posts related to it that’s condemnable no matter the content or circumstance. Ultimately it feels like we are watching an elaborate show of Xi’s stranglehold on the country. Perhaps that’s the point? This though is a view that can’t be shared on Weibo. Or at least not for long.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ak Welsapar, Julian Baggini, Alison Flood, Jean-Paul Marthoz and Victoria Pavlova”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

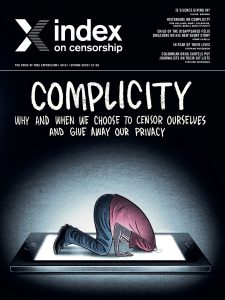

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Willingly watched by Noelle Mateer: Chinese people are installing their own video cameras as they believe losing privacy is a price they are willing to pay for enhanced safety

The big deal by Jean-Paul Marthoz: French journalists past and present have felt pressure to conform to the view of the tribe in their reporting

Don’t let them call the tune by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: A professor debates the moral questions about speaking at events sponsored by an organisation with links to the Chinese government

Chipping away at our privacy by Nathalie Rothschild: Swedes are having microchips inserted under their skin. What does that mean for their privacy?

There’s nothing wrong with being scared by Kirsten Han: As a journalist from Singapore grows up, her views on those who have self-censored change

How to ruin a good dinner party by Jemimah Steinfeld: We’re told not to discuss sex, politics and religion at the dinner table, but what happens to our free speech when we give in to that rule?

Sshh… No speaking out by Alison Flood: Historians Tom Holland, Mary Fulbrook, Serhii Plokhy and Daniel Beer discuss the people from the past who were guilty of complicity

Making foes out of friends by Steven Borowiec: North Korea’s grave human rights record is off the negotiation table in talks with South Korea. Why?

Nothing in life is free by Mark Frary: An investigation into how much information and privacy we are giving away on our phones

Not my turf by Jemimah Steinfeld: Helen Lewis argues that vitriol around the trans debate means only extreme voices are being heard

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: You’ve just signed away your freedom to dream in private

Driven towards the exit by Victoria Pavlova: As Bulgarian media is bought up by those with ties to the government, journalists are being forced out of the industry

Shadowing the golden age of Soviet censorship by Ak Welsapar: The Turkmen author discusses those who got in bed with the old regime, and what’s happening now

Silent majority by Stefano Pozzebon: A culture of fear has taken over Venezuela, where people are facing prison for being critical

Academically challenged by Kaya Genç: A Turkish academic who worried about publicly criticising the government hit a tipping point once her name was faked on a petition

Unhealthy market by Charlotte Middlehurst: As coronavirus affects China’s economy, will a weaker market mean international companies have more power to stand up for freedom of expression?

When silence is not enough by Julian Baggini: The philosopher ponders the dilemma of when you have to speak out and when it is OK not to[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Generations apart by Kaya Genç and Karoline Kan: We sat down with Turkish and Chinese families to hear whether things really are that different between the generations when it comes to free speech

Crossing the line by Stephen Woodman: Cartels trading in cocaine are taking violent action to stop journalists reporting on them

A slap in the face by Alessio Perrone: Meet the Italian journalist who has had to fight over 126 lawsuits all aimed at silencing her

Con (census) by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Turns out national censuses are controversial, especially in the countries where information is most tightly controlled

The documentary Bolsonaro doesn’t want made by Rachael Jolley: Brazil’s president has pulled the plug on funding for the TV series Transversais. Why? We speak to the director and publish extracts from its pitch

Queer erasure by Andy Lee Roth and April Anderson: Internet browsing can be biased against LGBTQ people, new exclusive research shows[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Up in smoke by Félix Bruzzone: A semi-autobiographical story from the son of two of Argentina’s disappeared

Between the gavel and the anvil by Najwa Bin Shatwan: A new short story about a Libyan author who starts changing her story to please neighbours

We could all disappear by Neamat Imam: The Bangladesh novelist on why his next book is about a famous writer who disappeared in the 1970s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Demand points of view by Orna Herr: A new Index initiative has allowed people to debate about all of the issues we’re otherwise avoiding[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Ticking the boxes by Jemimah Steinfeld: Voter turnout has never felt more important and has led to many new organisations setting out to encourage this. But they face many obstacles[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”112844″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]When the political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson wrote about nations in his 1983 book Imagined Communities, he said that belonging to them was particularly felt at certain moments. Reading the daily newspaper for one; watching those 11 men representing your country on the football field another. If Anderson were alive today, he might add “getting a government text message” to the list. Last Tuesday people throughout the UK all shared in this experience. Following Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s announcement the night before that we must all stay in, with few exceptions, the nation’s phones pinged to the alert “New rules in force now: you must stay at home. More info and exemptions at gov.uk/coronavirus Stay at home. Protect the NHS. Save lives.” It was a first. The government had never before used the UK’s mobile networks to send out a message on mass.

By “force” the message meant exactly that. Police now have the power to fine those who flout the new rules. Quickly videos have emerged of officers approaching people on the streets, such as one showing sunbathers in Shepherd’s Bush being told to leave, and photos of a 25-person strong karaoke party that was dispersed this weekend. Almost overnight we went from being a nation where most people could come and go as they pleased to one in which we can barely leave our front door.

State-of-emergency measures are necessary in a real crisis, which is where we land today. Hospital beds are filling up fast, the death toll is rising, the threat of contagion is real and high. Few would argue that something drastic didn’t need to be done. But that does not mean we should blindly accept all that is happening in the name of our health. Proportionality – whether the measures are a justified or over-reaching response to the current danger – and implication – how they could be used in other aspects – are questions we should and must ask.

The new rules of UK life have been enshrined in the Coronavirus Bill. The bill, a complex and lengthy affair, gives the government a lot of power. Take for example the rules that allow authorities to isolate or detain individuals who are judged to be a risk to containing the spread of Covid-19. What exactly does a risk mean? Would it be the journalist Kaka Touda Mamane Goni from Niger, who last week was arrested because he spoke of a hospital that had a coronavirus case and was quickly branded a threat to public order? Or how about Blaž Zgaga, a Slovenian journalist who contacted Index several weeks back to say he had been added to a list of those who have the disease (something he denies) and must be detained? This followed him calling up the government on their own coronavirus tactics. He’s currently terrified for his life.

It’s easy to dismiss these examples as ones that are happening elsewhere and not here, until one day we wake up and that’s no longer the case.

And while many of us might be far away from authoritarian nations like China, whose government is tracking people’s movements through a combination of monitoring people’s smartphones, utilising now ubiquitous video surveillance and insisting people report their current medical condition, it might only be a matter of time before we catch up.

Singapore, another country with a state that has a tight grip on its population, has already offered to make the app they’re currently using to track exposure to the virus available to developers worldwide. The offer is free but at what other costs? The Singaporean government has been working hard to allay privacy concerns and yet some linger. Will people invite this new technology in their lives? Amid the panic that coronavirus has created, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which such tools are imported, embraced and normalised. As Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harrari writes in the FT:

“A big battle has been raging in recent years over our privacy. The coronavirus crisis could be the battle’s tipping point. For when people are given a choice between privacy and health, they will usually choose health.”

The coronavirus bill was meant to come with an expiry date, a “sunset clause” of two years, at which stage all former laws fall back into place. The sunset clause has since been removed, and instead in its place is a clause stating the legislation will be reviewed every six months. Politicians have also sought assurances that the measures will only apply to fighting the virus, to which they have been told yes they will only be used “when strictly necessary” and will remain in force only for as long as required. All positive and stuff we should welcome. And yet how often do politicians say one thing and do another? We must be watchful and hold them to their word.

This is particularly important with the clause that enables authorities to close down, cancel or restrict an event or venue if it poses a threat to public health, a clause that has bad implications for the ability to protest. Of course in the digital age there are many ways beyond going out on to the streets to make your voice heard. And even without the internet, we’ve seen several creative forms of protest from inside the home, such as the Brazilians who have shouted “get out” and bashed kitchenware at the window as a way to voice anger at President Jair Bolsonaro.

Marching on the streets in huge numbers is, however, amongst the most effective, hence its endurance. If in six months’ time the virus is under control and social distancing is no longer essential, this clause should at point-of-review be removed. And if it isn’t, we need to fight really hard until it is. Protest is one of the key foundations of a robust civil society. It’s not a right we want to see disappear.

The great British philosopher John Stuart Mill argued in On Liberty that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

The coronavirus crisis passes Mill’s liberty test. It is causing harm to a great number of people. It’s therefore important to take it seriously and to provide the state with adequate powers to fight the pandemic, even if that means losing some of our freedoms in the here and now. At the same time we must make sure politicians do not use this moment to tighten their grip in ways that, as stated, are disproportionate and easily manipulated. And once this is all over we expect the bill to expire too, and any apps that might no longer be necessary. Our freedoms, so hard fought for, can be easily squandered. Let’s not lose liberties on top of lives.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]