16 Nov 2022 | BannedByBeijing, China, News and features

Twenty-three years after writing his best known work, Red Star Over China, Edgar Snow returned to China in 1960 to investigate claims that a radical agrarian reform programme had resulted in devastating famine. “I diligently searched, without success, for starving people or beggars to photograph … I do not believe there is famine in China,” Snow wrote.

Snow was wrong. The famine in China was both real and devastating. It is estimated as many as 30 million died in it. Snow’s bias lens had ghostly echoes with Walter Duranty’s reporting from Ukraine, during the Holodomor, the mass famines engineered by Stalin. Only when faced with overwhelming evidence did he eventually concede that the genocide occurred, “to put it brutally – you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs” he said.

In information vacuums, common during times of conflict such as the civil conflict in Syria, as well as in areas controlled by authoritarian regimes, reporting from independent journalists can quickly define or redefine the public’s perception of a regime or situation. While journalists can play a powerful role in challenging censorship and propaganda from the state, they can also act as the state’s servants. Such was the case for both Snow and Duranty, whose rose-tinted views of the countries impacted global perceptions. Herein lies the point – those who claim to be independent reporters can be incredibly useful to the state, sometimes more so than those working within state media, because the notion that they are independent carries with it a level of authority and weight.

The use of “junket journalism” to obscure reporting on crimes against humanity has only grown in prominence and sophistication. Nowhere has this been more evident than in China where the government has co-opted a range of journalists and social media influencers to help strengthen the CCP’s control over its narrative and obscure legitimate scrutiny of a number of important issues, most notably the genocide of the Uyghur population. Recent party documents and officials have emphasised the need to bolster the CCP political line, and inject positivity into the CCP and China’s image. Current President Xi Jinping said, “Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their new tentacles”.

A recent International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) survey confirmed that “China is conducting a media outreach campaign in almost every continent” with the 31 developed and 27 developing countries that participated in the survey similarly targeted. The researchers told the Guardian, “China is also wooing journalists from around the world with all-expenses-paid tours and, perhaps most ambitiously of all, free graduate degrees in communication, training scores of foreign reporters each year to ‘tell China’s story well’”.

While many other countries, including established democracies, have sought to influence and shape independent reporting through tours, capacity building opportunities and other tactics, the CCP’s overt prioritisation of journalism that “depends upon a narrative discipline that precludes all but the party-approved version of events” raises significant concerns as to its intentions.

In this effort to shape global news, the CCP is advantaged by its huge pockets. It has spent around $6.6 billion since 2009 on strengthening its global media presence, supposedly investing over $2.8 billion alone in media and adverts. Sarah Cook, NED reporter and researcher, emphasised that “no country is immune”.

This ambition is best summarised by the Belt and Road News Network (BRNN), which includes 182 media organisations from 86 countries as members, and a Council, which includes 26 countries, including Spain, France, Russia, Netherlands and the UK. The launch of the BRNN was announced in a paid advertorial in The Telegraph produced by People’s Daily. In September 2019, BRNN hosted a workshop for international journalists in Beijing as part of the 70th anniversary celebrations of the People’s Republic of China, which was organised in partnership with the State Council Information Office of China. It included a visit to the offices of People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency and other “central media units”, as well as trips to “Shaanxi, Zhejiang, Guizhou and Guangdong provinces for interviews and researches in order to personally experience China’s unremitting efforts and fruitful results in poverty alleviation, ecological civilization, big data industry, urban planning, and independent intellectual property rights.”

While the workshop was attended by representatives from 46 mainstream media outlets from 26 Latin American and African countries, it would be overly simplistic to suggest that China is only focusing on countries from the global south. Since 2009, the China-United States Exchange Foundation (CUSEF) has taken 127 US journalists from 40 US outlets to China. This foundation has been identified as working with China’s United Front as highlighted by US Senator Ted Cruz, in a letter to the President of the University of Texas at Austin, who stated that “[t]oday, CUSEF and the united front are the external face of the CCP’s internal authoritarianism”.

The IFJ report notes that “the Chinese Embassy has sought out journalists working for Islamic media, organising special media trips to showcase Xinjiang as a travel destination and an economic success story.” Xinjiang and the treatment of Uyghur communities is a prominent area in which the CCP has focused its efforts. After a visit to Xinjiang, Harald Brüning, author and director of the Macau Post Daily, stated that “the anti-China forces’ allegations of genocide are preposterous judging by what the Macao journalists, most of whom had not visited the region before, saw and heard in Xinjiang.” In his piece, Brüning did not disguise the genesis of his trip, exclaiming in the third paragraph “[t]he extraordinarily well-organised tour took place at the invitation of the Office of the Commissioner of the Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China in the Macao Special Administrative Region.” The piece is heavily framed around rebutting existing reporting – labelled in the piece as lies – including the use of forced labour in the cotton fields of Xinjiang, as well as decrying the “brutality the religious extremists and separatists [have] resorted to”.

However an all-expenses paid junket does not guarantee full control of a journalist’s coverage. Olsi Jazexhi (below), a Muslim Canadian-Albanian journalist and historian sought a way to travel to Xinjiang because he was sceptical of the dominant narrative in the West that Muslims were being oppressed in China. He approached the Chinese embassy in Albania who invited him on a trip to Xinjiang with other “China-friendly journalists”. Once in Xinjiang, Jazexhi was shocked by the detainees’ testimonies of having been jailed for simple expressions of their religious identity, such as reading the Quran or encouraging others to pray. In Urumqi, he was lectured by state officials who equated Islam with terrorism and was shocked by the number of empty mosques or those repurposed into stores.

Olsi Jazexhi (right) listens to a handler during a tour of a mosque in Aksu city, Xinjiang in August 2019. Photo: Provided by Olsi Jazexhi

Other journalists who have tried to move away from the organised tours have faced a number of difficulties. When journalists have attempted to film camps that the government has not previously cleared for access, they have been turned away by local authorities. Road works or car crashes suddenly block their way and when the journalists attempt to return the next day, the roadworks suddenly reappear again. Members of a Reuters crew reported being tailed by a rotating cast of plain-clothed minders and “within an hour of the reporters leaving their hotel in the city of Kashgar through a back gate, barbed wire was erected across the exit and fire escapes on their floor were locked.”

While influencing journalists can sometimes be difficult, the expansion of blogging and social media influencing has opened up another avenue for state intervention. Travel vloggers who visit authoritarian countries say they just want to educate their viewers and avoid politics. Irish travel vlogger Janet Newenham told Al Jazeera after a controversial visit to Syria that “every country deserves to be shown in a different way and in a positive light even if most stuff about there has always been negative”. However, what can seem innocuous can take on more explicit political implications. “A lot of these vloggers are saying they’re apolitical in this and I’m sure that they are but the issue is, when you’re entering a conflict zone, your direct presence there becomes political,” researcher and adjunct professor, Sophie Kathyrn Fullerton told Al Jazeera.

A similar trend is increasingly evident in China. “I’m here because lots of people, right now, outside of China, want to know what Xinjiang is like,” says British vlogger, The China Traveller, at the start of a video, which focuses on him sampling a variety of local food while Uyghur women appeared to spontaneously dance behind him. Videos of this genre can be seen as part of what has been labelled the CCP’s project to “Disneyfy” Xinjiang. Uyghur culture has been co-opted by the state and amplified as a tourist attraction to change the narrative and drown out reports of genocide against the Uyghur community. In another video, The China Traveller praises the central government for rebuilding sections of the city, while failing to address the government’s other influence on the Xinjiang skyline: the mass demolition of religious institutions.

While Chinese culture is celebrated by The China Traveller and other vloggers in Xinjiang, French photographer Andrew Wack had a different experience when he returned to the region in 2019. Speaking to Wired a year after his trip, Wack commented on the stark absence of “men aged 20 to 60, many of whom had likely been rounded up and herded into indoctrination camps”. Throughout his visit, he was followed by plain-clothes police officers “and at checkpoints he was sometimes asked to show his photographs. On one occasion, he was asked to delete images”.

Many vloggers and journalists obscure any coordination or funding from Chinese bodies, or underplay how it may affect their coverage. Lee Barrett, a British vlogger, states in a video, “we go on some sponsored trips to places … our accommodation is paid for, our travel is paid for … nobody tells us what to say, nobody tells us what to film”. Due to the opaque nature of these relationships, it is impossible to interrogate the influence this type of support has on the vloggers’ reporting. However at times this veil is lifted. In a number of popular videos, minders sent by the Chinese state to monitor another vloggers’ trip can be clearly seen monitoring their behaviour.

When the BBC’s lead China reporter, John Sudworth, was invited into Xinjiang’s ‘re-education’ camps, he was presented with a highly choreographed and Disneyfied presentation of Xinjiang culture, which apparently even moved the Chinese officials accompanying the BBC crew to tears. However, Sudworth’s commitment to “peer beneath the official messaging and hold it up to as much scrutiny as we could” led him to scrutinise everything, including scraps of graffiti written in Uyghur and Chinese. This approach has had lasting consequences; he now reports on China from abroad, having had his visa revoked.

In modern day China, independent reporting from foreigners is one of the few avenues left in order to scrutinise power beyond the dominant state narrative. However, through the funding and coordination of junkets, training opportunities and other tactics, the Chinese state has followed in the footsteps of Assad’s Syria to try and control the message these foreigners send out into the world. This turns the principles of journalism against itself and manipulates the free expression environment in favour of the state.

Edgar Snow remains venerated in China. In 2021, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying proclaimed on Twitter: “China hopes to see and welcome more Edgar Snows of this new era among foreign journalists”. John Sudworth provides a powerful counterweight, reminding us that we must “peer beneath the official messaging and hold it up to as much scrutiny as we could”.

- The authors approached The China Traveller and Lee Barrett for comment for this article. No response had been received by the time of going to press.

12 Aug 2022 | Magazine, News and features, Student Reading Lists

Salman Rushdie. Credit: Fronteiras do Pensamento

On 12 August 2022, Salman Rushdie, the author of the book The Satanic Verses, was attacked as he prepared to give a lecture at the Chautauqua Institution, an arts and education centre in New York state.

Index on Censorship has supported Rushdie’s right to express himself ever since he came into the public eye more than three decades ago.

On 14 February 1989 Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to execute Rushdie over the publication of The Satanic Verses, along with anyone else involved with the novel.

Published in the UK in 1988 by Viking Penguin, the book was met with widespread protest by those who accused Rushdie of blasphemy and unbelief. Death threats and a $6 million bounty on the author’s head saw him take on a 24-hour armed guard under the British government’s protection programme.

The book was soon banned in a number of countries, from Bangladesh to Venezuela, and many died in protests against its publication, including on 24 February when 12 people lost their lives in a riot in Bombay, India. Explosions went off across the UK, including at Liberty’s department store, which had a Penguin bookshop inside, and the Penguin store in York.

Book store chains including Barnes and Noble stopped selling the book, and copies were burned across the UK, first in Bolton where 7,000 Muslims gathered on 2 December 1988, then in Bradford in January 1989. In May 1989 between 15,000 to 20,000 people gathered in Parliament Square in London to burn Rushdie in effigy.

In October 1993, William Nygaard, the novel’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times outside his home in Oslo and seriously injured.

Rushdie came out of hiding after nine years, but as recently as February 2016, money has been raised to add to the fatwa, reminding the author As that for many the Ayatollah’s ruling still stands.

As his supporters around the world, including Index, pray for a positive outcome, we highlight key articles from our archives from before, during and after the issue of the fatwa, including two from Rushdie himself.

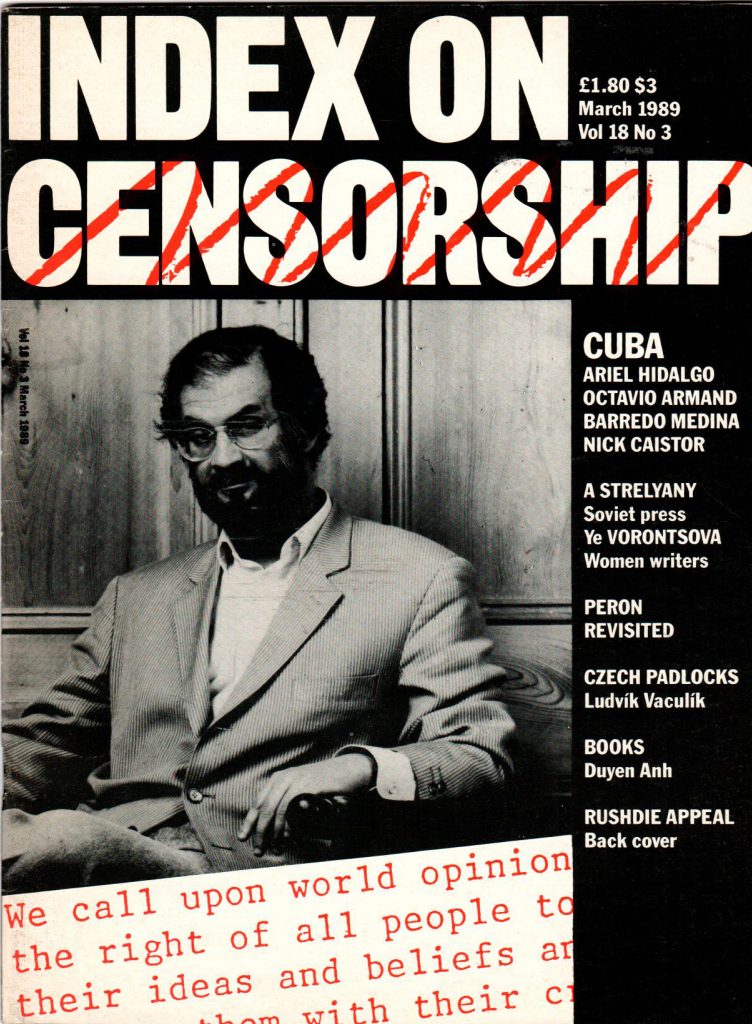

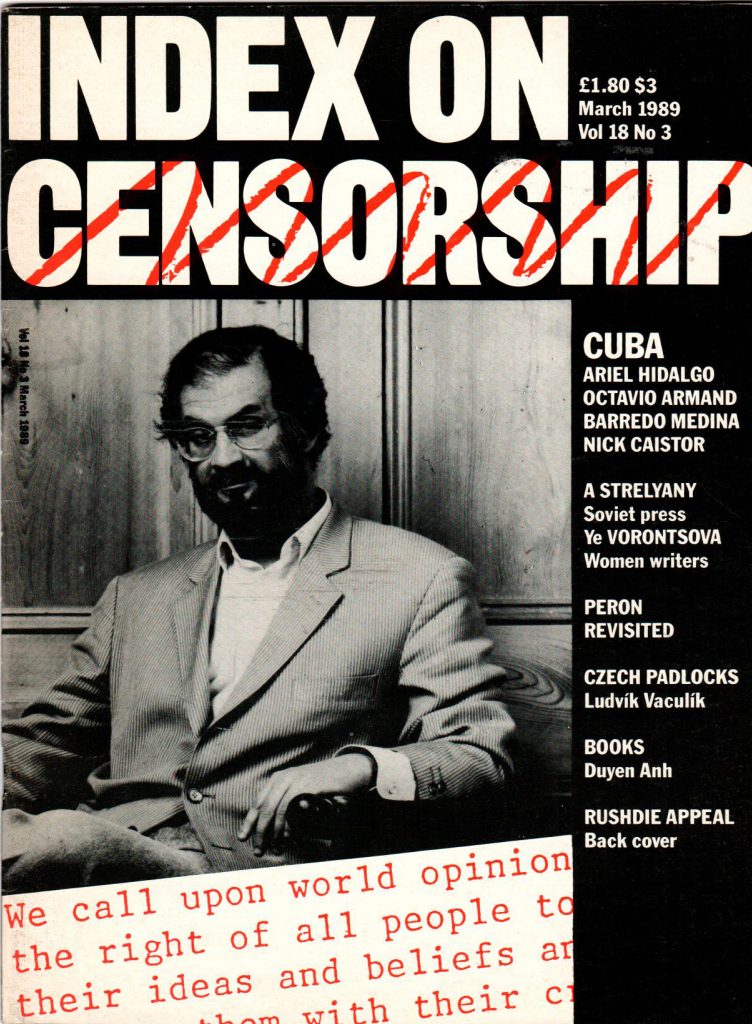

Cuba today, the March 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

World statement by the international committee for the defence of Salman Rushdie and his publishers

March 1989, vol. 18, issue 3

On 14 February the Ayatollah Khomeini called on all Muslims to seek out and execute Salman Rushdie, the author of The Satanic Verses, and all those involved in its publication. We, the undersigned, insofar as we defend the right to freedom of opinion and expression as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, declare that we also are involved in the publication. We are involved whether we approve the contents of the book or not. Nonetheless, we appreciate the distress the book has aroused and deeply regret the loss of life associated with the ensuing conflict.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Pandora’s box forced open

Amir Taheri

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

‘What Rushdie has done, as far as Muslim intellectuals are concerned, is to put their backs to the wall and force them to make the choice they have tried to avoid for so long’. Last year, when poor old Mr Manavi filled in his Penguin order form for 10 copies of Salman Rushdie’s third novel, The Satanic Verses, he could not have imagined that the book, described by its publishers as a reflection on the agonies of exile, would provoke one of the most bizarre diplomatic incidents in recent times. Mr Manavi had been selling Penguin books in Tehran for years. He had learned which authors to regard as safe and which ones to avoid at all costs.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Jihad for freedom

Wole Soyinka

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

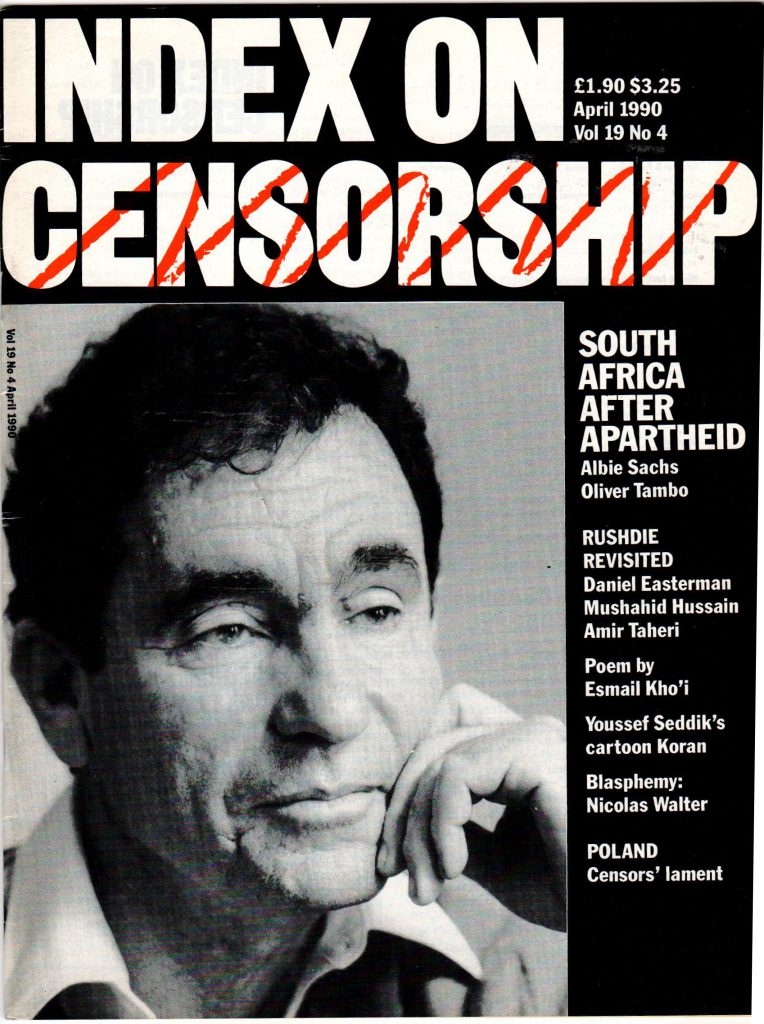

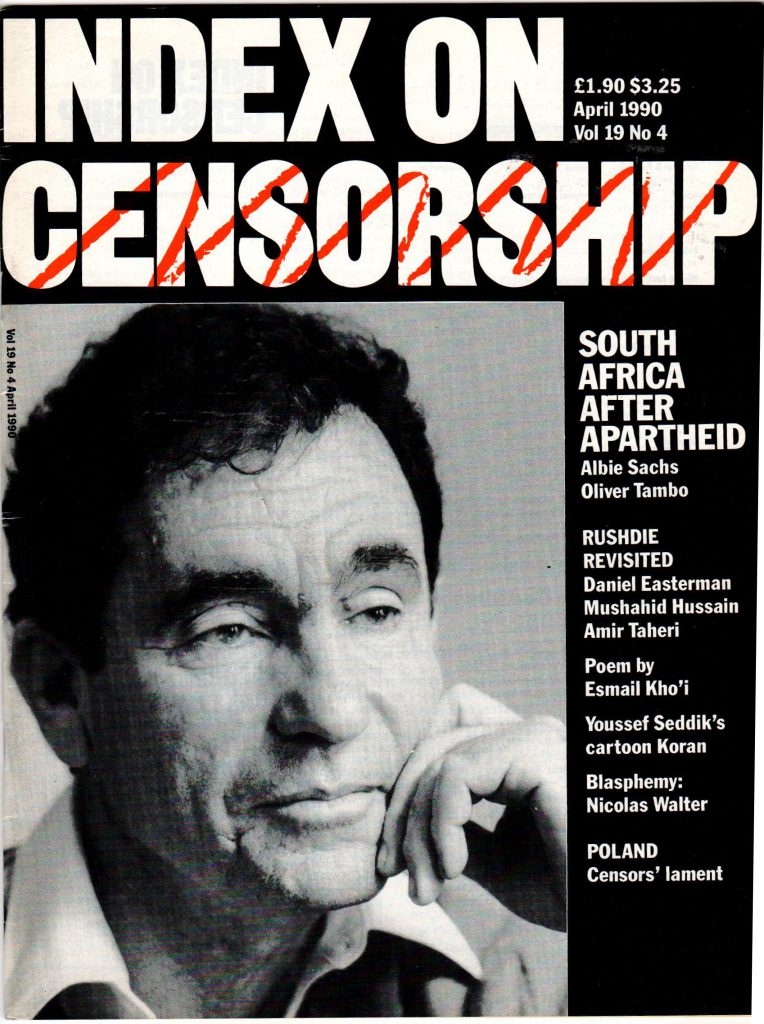

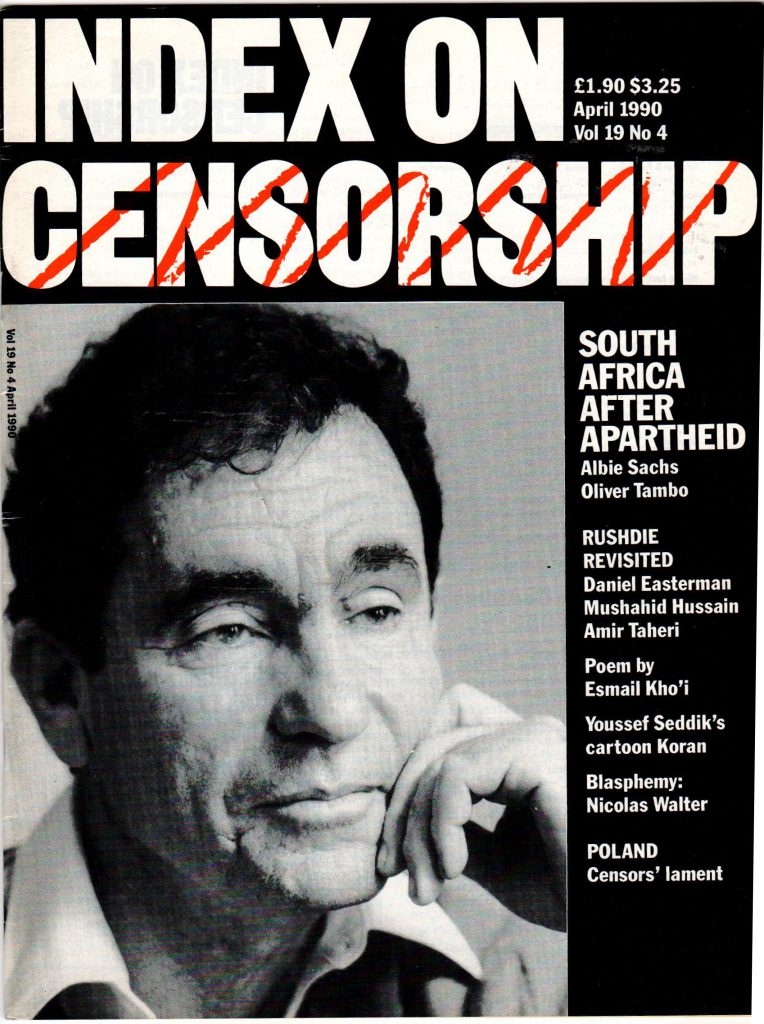

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Reflections on an invalid fatwah

Amir Taheri

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

Broadly speaking, three predictions were made. The first was that Khomeini’s attempt at exporting terror might goad world public opinion into a keener understanding of Iran’s tragedy since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The fact that the Ayatollah had executed thousands of people, including many writers and poets since his seizure of power in Tehran had provoked only mild rebuke from Western governments and public opinion. With the fatwa against Rushdie, we thought the whole world would mobilise against the ayatollah, turning his regime into an international pariah. Nothing of the kind happened, of course, and only one country, Britain, closed its embassy in Tehran – and that because the mullahs decided to sever.diplomatic ties. In the past twelve months Federal Germany and France have increased their trade with the Islamic Republic to the tune of II and 19 per cent respectively. The EEC countries and Japan have, in the meantime, provided the Islamic Republic with loans exceeding £2,000 million. The stream of European and Japanese businessmen and diplomats visiting Tehran turned into a mini-flood after Khomeini’s death last June.

Read the full article

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Salman Rushdie and political expediency

Adel Darwish

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

When I reviewed Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in September 1988, it never crossed my mind to make any reference to possible offence to Muslim readers, let alone to anticipate the unprecedented international crisis generated in the months that followed. I do not think I was naive – as an LBC radio reporter suggested when she interviewed me at the first public reading from The Satanic Verses in June 1989. On the contrary, I can claim more than many that I am able to understand what Mr Rushdie was trying to say in his book, and the way the crisis has developed. Like Mr Rushdie, I am a British writer, born to a Muslim family. Born in Egypt, I was educated and am employed in Britain, and have been preoccupied and engaged, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s, with the issues that Mr Rushdie has fought for and with which he seemed to be very much concerned in his book.

Read the full article

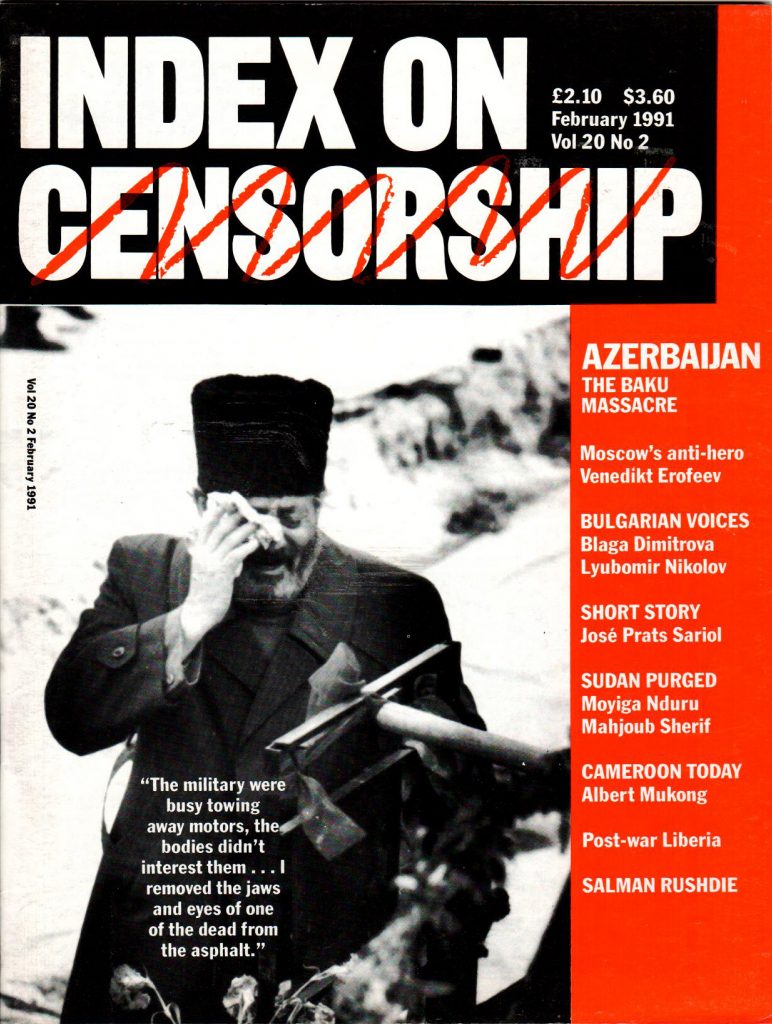

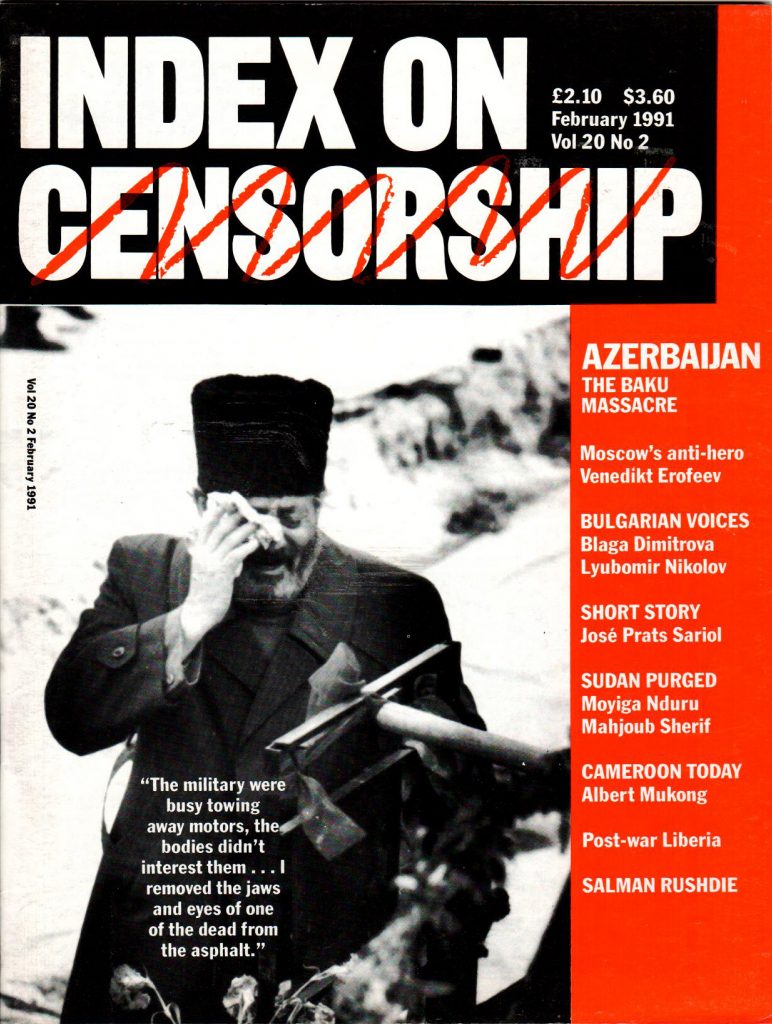

Azerbaijan, the February 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

My decision

Salman Rushdie

February 1991, vol. 20, issue 2

A man’s spiritual choices are a matter of conscience, arrived at after deep. reflection and in the privacy of his heart. They are not easy matters to speak of publicly. I should like, however, to say something about my decision to affirm the two central tenets of Islam — the oneness of God and the genuineness of the prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad —and thus to enter into the body of Islam after a lifetime spent outside it. Although I come from a Muslim family background, I was never brought up as a believer, and was raised in an atmosphere of what is broadly known as secular humanism. I still have the deepest respect for these principles. However, as I think anyone who studies my work will accept, I have been engaging more and more with religious belief, its importance and power, ever since my first novel used the Sufi poem Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-din Attar as a model. The Satanic Verses itself, with its portrait of the conflicts between the material and spiritual worlds, is a mirror of the conflict within myself.

Read the full article

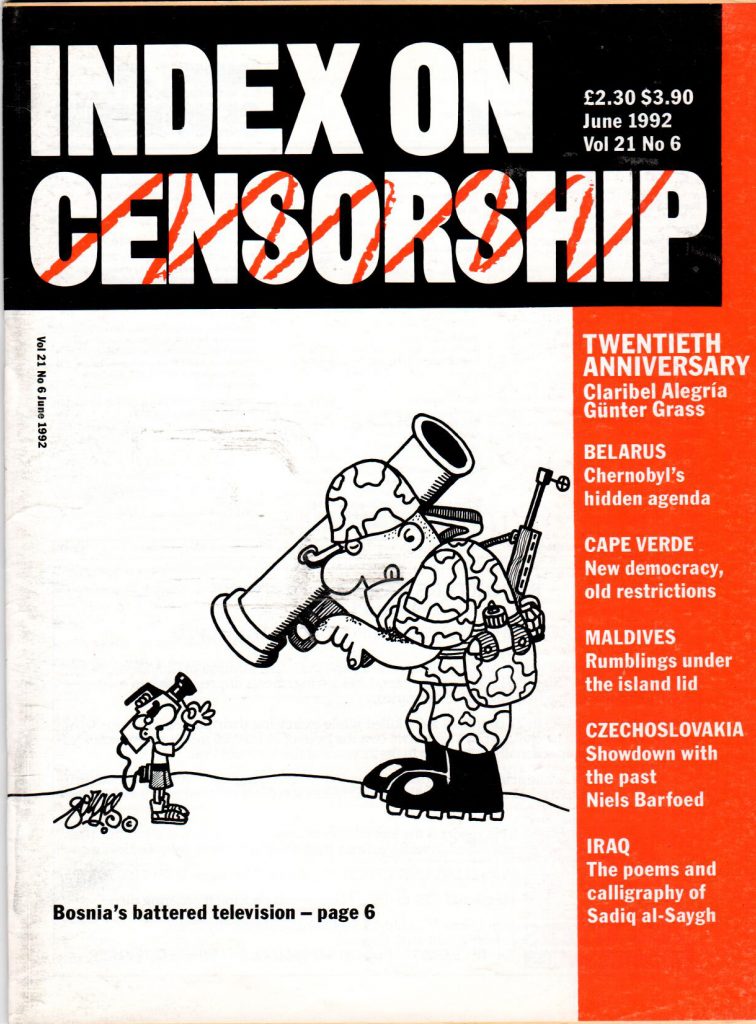

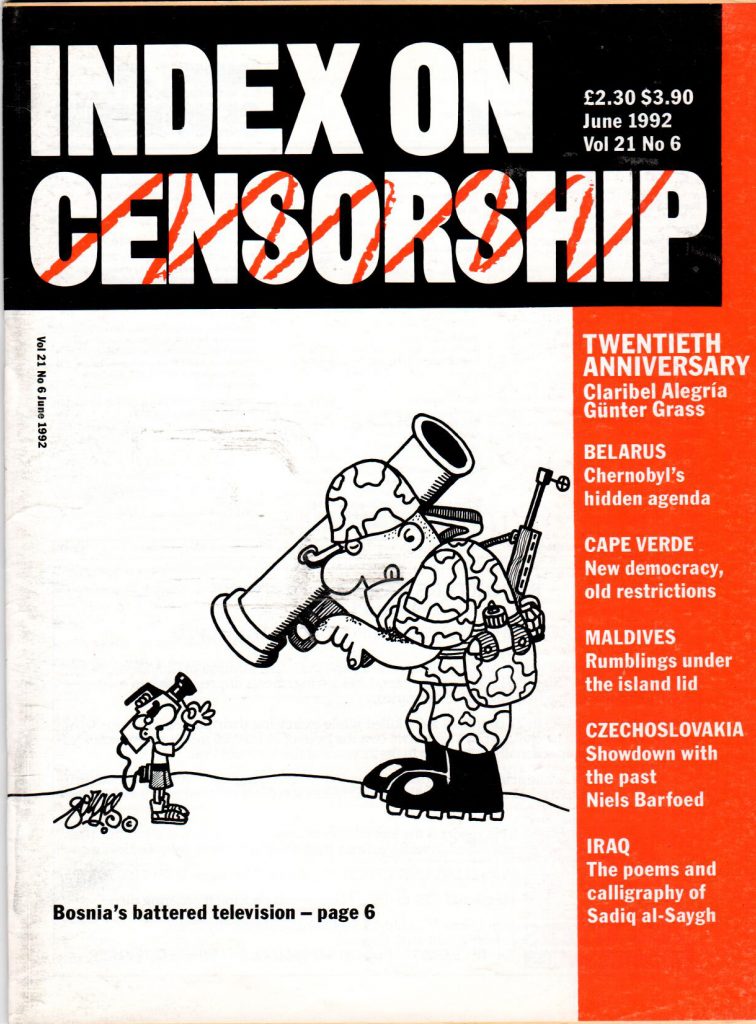

20th Anniversary: Reign of terror, the June 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Offending the high priests

Gunter Grass

June 1992, vol. 21, issue 6

When George Orwell returned from Spain in 1937, he brought with him the manuscript of Homage to Catalonia. It reflected the experiences he had gathered during the Civil War. At first, he was unable to find a publisher because a multitude of influential, left-wing intellectuals had no wish to acknowledge its shocking observations. They did not want to accept the Stalinist terror, the systematic liquidation of anarchists, Trotskyists and left-wing socialists. Orwell himself only narrowly escaped this terror. His stark accusations contradicted a world image of a flawless Soviet Union fighting against Fascism. Orwell’s report, this onslaught of terrible reality, tarnished the picture-book dream of Good and Evil. A year later, a bourgeois Western publisher brought out Homage to Catalonia; in the areas of Communist rule, Orwell’s works – among them the bitter Spanish truth – were banned for half a century. The minister responsible for state security= in the German Democratic Republic, right to its end, was Erich Mielke. During the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the Communist cadre to whom purge through liquidation became commonplace. A fighter for Spain with an extraordinary capacity for survival.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Russia’s choice, the November-December 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Rushdie affair: Outrage in Oslo

Hakon Harket

November 1993, vol. 22, issue 10

The terrorist state of Iran must face the consequences of refusing to lift the fatwa that condemns Salman Rushdie, and those associated with his work, to death. When someone, in accordance with the express order of the fatwa, attempts to murder one of the damned, the obvious consequence is that Iran must be held responsible for the crime it has called for, at least until there is conclusive proof that no connection exists. The shooting of William Nygaard has reminded the Norwegian public of what the Rushdie affair is really about: life and death; the abuse of religion; the fiction of a free mind. This war of terror against freedom of speech is not one we can afford to lose. Since the nightmare clearly will not disappear of its own accord, it must be engaged head-on.

Read the full article

New censors, the March 1996 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

From Salman Rushdie

March 1996, vol. 25, issue 2

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

The Rushdie affair: Outrage in Oslo

Hakon Harket

November 1993, vol. 22, issue 10

The terrorist state of Iran must face the consequences of refusing to lift the fatwa that condemns Salman Rushdie, and those associated with his work, to death. When someone, in accordance with the express order of the fatwa, attempts to murder one of the damned, the obvious consequence is that Iran must be held responsible for the crime it has called for, at least until there is conclusive proof that no connection exists. The shooting of William Nygaard has reminded the Norwegian public of what the Rushdie affair is really about: life and death; the abuse of religion; the fiction of a free mind. This war of terror against freedom of speech is not one we can afford to lose. Since the nightmare clearly will not disappear of its own accord, it must be engaged head-on.

Read the full article

New censors, the March 1996 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

From Salman Rushdie

March 1996, vol. 25, issue 2

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

Tolerance and the intolerable, the May 1994 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Bosnia on my mind

Salman Rushdie

May 1994, vol. 23, issue 1-2

When the Balkans War broke out, Rushdie had never been to Sarajevo, but felt that he belonged to it. He imagined a Sarajevo of the mind, whose ruination and torment exiled everyone.

He wrote: “Sarajevo’s truth is that its citizens, who reject definition by religion or confession, who wish to be simply Bosnians, have for their pains been labelled by the outside world as ‘Muslims’. It is instructive to imagine how things might have gone in former Yugoslavia if the Bosnians had been Christians and the Serbs had been Muslims, even Muslims ‘in name only’. Would Europe have supported a ‘Serbian Muslim’ carve-up of the defunct state? It’s only a guess, but I guess that it would not. Which being true, it must also be true that the ‘Muslim’ tag is part of the reason for Europe’s indifference to Sarajevo’s fate.”

Read the full article

The right to publish

The right to publish

Peter Mayer

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Penguin published Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses six months before Ayatollah Khomeini issues his fatwa. When we decided to continue publishing the novel in the aftermath, extraordinary pressures were focused on our company, based on fears for the author’s life and for the lives of everyone at Penguin around the world. This extended from Penguin’s management to editorial, warehouse, transport, administrative staff, the personnel in our bookshops and many others. The long-term political implications of that early signal regarding free speech in culturally diverse societies were not yet apparent to many when the Ayatollah, speaking not only for Iran but, seemingly, for all of Islam, issued his religious proclaimation.

Read the full article

Emblem of darkness

Emblem of darkness

Bernard-Henri Lévy

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Salman Rushdie was not yet the great man of letters that he has since become. He and I are, though, pretty much the same age. We share a passion for India and Pakistan, as well as the uncommon privilege of having known and written about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (Rushdie in Shame; I in Les Indes Rouges), the father of Benazir, former prime minister of Pakistan, executed ten years earlier in 1979 by General Zia. I had been watching from a distance, with infinite curiosity, the trajectory of this almost exact contemporary. One day, in February 1989, at the end of the afternoon, as I sat in a cafe in the South of France, in Saint Paul de Vence, with the French actor Yves Montand, sipping an orangeade, I heard the news: Ayatollah Khomeini, himself with only a few months to live, had just issued a fatwa, in which he condemned as an apostate the author of The Satanic Verses and invited all Muslims the world over to carry out the sentence, without delay.

Read the full article

40 years of Index on Censorship March 2012

Last chance?

Salman Rushdie

March 2012, vol. 41, issue 1

Salman Rushdie’s first memories of censorship are cinematic: screen kisses brutalised by prudish scissors which chopped out the moments of actual contact. (Briefly, before comprehension dawned, he wondered if that were all there was to kissing, the languorous approach and then the sudden turkey-jerk away.) The effect was usually somewhat comic, and censorship still retains, in contemporary Pakistan, a strong element of comedy. When the Pakistani censors found that the movie El Cid ended with a dead Charlton Heston leading the Christians to victory over live Moslems, they nearly banned it until they had the idea of simply cutting out the entire climax, so that the film as screened showed El Cid mortally wounded. El Cid dying nobly, and then it ended. Muslims 1, Christians 0.

Read the full article

The winter 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Defending the right to be offended

Samira Ahmed

December 2013, vol. 42, issue 4

The tensions between freedom of speech and religious belief remain acute – and they are systematically exploited by political groups of all stripes, from the English Defence League to radical Islamists who threaten to disrupt the repatriation of dead British soldiers at Wootton Bassett. The story consistently makes the headlines. The idea that there is an Islamist assault on British freedoms and values is widespread.

The Muslim campaign against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 was the crucial moment in all this. It forced writers and artists from an Asian or Muslim background, whether they defined themselves that way or not, to take sides. They had to declare loyalty – or otherwise – to the offended.

Read the full article

4 Aug 2022 | Ruth's blog

On the hottest day of the year, the professional team at Index was due to have an in-person brainstorming session about what might come our way next and what we needed to be prepared for. Our away day quickly became a virtual session with everyone melting in the heat.

In the midst of the conversation, one of my brilliant team members described one part of her work, that on SLAPPs (strategic lawsuits against public participation), as challenging reputation laundering. While that’s exactly what she’s been doing, I haven’t been able to move on from that phrase.

As unimpeded access to information becomes the norm in democracies in the 21st century, it might be easy to assume that rewriting history to agree with your own world view would be almost impossible. It feels, however, increasingly naive to believe that immediate access to this sheer volume of news and information is actually protecting truth. We face misinformation and propaganda campaigns at a state actor level, single issue activists, the misuse of libel laws and the increasing use of SLAPPs, as well as outright lies by bad faith actors, making it difficult to determine the reality of a situation.

This is compounded when people are ashamed of their history or don’t have the tools to talk about it.

Which brings me to my holiday last week. I had a wonderful break in Barcelona with my partner, doing all the tourist stuff you do on a city break. But by the third day, it became clear that there was one thing that no one was talking about – the Spanish Civil War. The Barcelona picture book in our room didn’t mention it. The plaques around the city missed out great swathes of Barcelona’s history from 1936 until the mid 1970s. The civil war wasn’t even touched upon at the Maritime Museum or either of the two cathedrals we visited, which were sites of some of the revolts. And the city open-top bus tour (the ultimate tourist experience) mentioned neither Franco nor the fact that the city had been the site of some of the most violent clashes in the civil war. In fact, it didn’t even mention the civil war.

Our response was to read more and to join the Walking Museum of the Spanish Civil War in Barcelona (which was brilliant). But the more we read and the more we walked, the more I couldn’t move on. As we ate on La Ramblas, I watched tourists from around the world having an amazing time, but I wondered how many of them knew its history. In 1936, this was the site of a street battle where people were killed feet from where we now sat because they were adamantly fighting for democracy and freedom. When we walked past the Moka coffee shop, I wondered how many people eating a pastry realised that George Orwell had taken refuge there. And when we went to the anarchist bookshop (obviously required shopping on holiday), I wondered how many people walking past realised that its former staff led the fight against Franco’s fascists in the city.

After the fall of Franco, the Spanish decided that it was too difficult and too divisive to engage in a peace and reconciliation process. Instead, most political parties agreed to draw a line in the sand and move on, ignoring their immediate past. My experiences last week suggest that at least for corporate Spain that remains true, but the political reality for Spaniards is apparently now a little different. The whereabouts are still unknown of 114,000 people who disappeared under Franco’s regime, and their grandchildren want to know what happened to them. Now, there is a growing memory movement. Because political leaders failed to agree on an established factual version of Franco’s regime, there are now increasing tensions between the political left and the right as to what really happened, with revisionism and denialism an increasing theme in mainstream Spanish politics.

What I witnessed in Barcelona was not only an example of attempted reputation laundering – it was an effort to run from a country’s past, which I truly believe is impossible. But that’s only impossible because of us – the rest of us. We have to study and understand atrocities from the past and make sure that the truth will out. It is our ultimate responsibility as people who campaign to protect freedom of expression.