28 Feb 2018 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Recent developments in Turkey, once seen as a role model for the Muslim world, have shown that concepts such as the rule of law and right to free speech are no longer welcome by the Erdogan government.

With 156 journalists behind bars as of 26 February 2018 and the closing down of more than 150 media outlets by virtue of the state’s of emergency decrees, Turkey is the global leader in suppressing the media. The irony is that Erdogan was once a victim of an earlier oppressive regime in the late 1990s, having been dismissed as mayor of Istanbul, banned from political office and put in prison for three months for inciting religious hatred after he recited part of a poem by the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gokalp at a political rally.

The destruction of the rule of law in Turkey has been in the making since the anti-government Gezi Park protests and corruption probes of 2013. However, the government has made its intentions on the right to free speech crystal clear in the aftermath of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt. Many journalists and writers have been imprisoned over accusations as absurd as spreading subliminal messages to promote the coup.

Some of them — like Die Welt journalist Deniz Yucel — have languished in detention without charge for a year. Yucel was used as a bargaining chip against Germany and was only freed after chancellor Angela Merkel put pressure on the Turkish government. Immediately after he was let out of detention he published a video message in which he said: “I still don’t know why I was arrested and why I have been released.”

Ahmet Sik, another well-known journalist, was imprisoned because of his thorough investigations into the dark sides of the coup attempt. Can Dundar was arrested for publishing about Turkish intelligence’s illegal arms transfers to Syria. He was kept in prison for several months and eventually released on a constitutional court decision in February 2016. He fled the country and currently lives in Germany. Veteran journalists Sahin Alpay and Mehmet Altan, on the other hand, were not so lucky. They had been granted freedom by the constitutional court but a local court refused to implement their release. Recently, the Altan brothers, Mehmet and Ahmed, and another senior journalist, Nazli Ilicak, have been brutally sentenced to aggravated life prison sentences. Examples of the obscene unlawful imprisonment of journalists can go on and on.

The heart of the issue is that Turkish journalists do excellent work. They go to extraordinary efforts to make sure the public is informed about corruption, illegal arms transfers, extrajudicial killings of Kurds and minorities, shady affairs of the ruling party with the judiciary and unanswered questions about the coup attempt. The government doesn’t want to see these issues make headlines, and for defying it many journalists have sacrificed their freedom.

Behind the thin veneer of Turley’s judicial system is the political machine manufacturing countless crimes. After 500 days pretrial detention, Ahmet Turan Alkan, an intellectual and a respected writer, pointed that out by telling a judge: “Your honour, I know you can’t release me because if you decide to do so you will be jailed.”

Turkey’s journalists are faced with a unique problem: if they continue to lay bare the truth for all to see they risk exile or prison. In a normal country, journalists performing at the height of their abilities would be encouraged or rewarded, perhaps not by their governments but by the society as a whole. But not so in Turkey, where the government mouthpieces and politically-aligned media outlets spout the latest propaganda to manipulate Turks. Unfortunately, the majority of people actually believe that most of the arrested journalists are criminals or terror supporters.

This collective hostility to freedom of expression makes Turkey one of the biggest violators of press freedom in the 42 European-area countries Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project monitors; one of the lowest ranking countries in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index; and deemed “not free” by Freedom House’s evaluation.

It’s not just journalists. Academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and lawyers also face punishment for carrying out their professional responsibilities on behalf of the public. Disclosing the unlawful practices of those in power is all it takes for an individual to find themselves on the wrong side of the bars. As with Alpay and Altan, a court had ordered Taner Kilic, the chairman of Amnesty Turkey, to be released from detention, but the prosecutor put him back in prison. Kilic and his colleagues are being targeted in retribution for Amnesty International’s work to make the world aware of the inhumane conditions in Turkey’s post-coup attempt era.

The government’s intolerance toward dissenting voices can also be seen in its treatment of university professors, students and others who signed an Academics for Peace petition, which called for an end to violence in the Kurdish region of the country. Hundreds of distinguished academics have found themselves summoned to courtrooms. For taking a stand about the ongoing tragedy in Kurdish cities, the majority of these academics are dehumanised and defamed. They have not only become enemies of the state but enemies of all Turks.

Yes, the government has terrorised ordinary people with the narrative of the “world against great Turkey” and urged them to stand against outspoken figures who are the “spies, traitors and enemies”.

What do the EU and other international organisations do? Mostly expressing their “concern” in different formats such as “great”, “deep” or “serious”. Even the European Court of the Human Rights has not issued a single verdict against Turkey’s post-coup purge which has seen the country become the world’s largest jailer of journalists.

On the same day the Altan brothers were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison, Tjorbon Jaglan, the secretary general of the Council of Europe was on a two-day visit in Turkey. He didn’t utter a single word about their situation. What else could better fit the definition of the “banality of evil” conceptualised by Hannah Arendt?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519832159496-f7b69135-ce98-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Feb 2018 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dihaber reporters Erdoğan Alayumat (L) and Nuri Akman face up to 45 years in prison on terror and espionage charges.

All eyes turned to Erdoğan Alayumat when he appeared on the screen of the judicial teleconference system of a court in the southern province of Hatay on 2 February, beaming in from a prison 800 kilometres to the north on Turkey’s Black Sea coast. For someone facing up to 45 years in prison on terror and espionage charges, his face seemed serene and composed, his voice calm and collected.

“Had I been spying, there should be proof to show when, to whom and how I sent this information,” Alayumat told the judges of the Hatay second heavy penal court, displaying his journalistic reflex to remind the court that, like any news article, the principles of basic information shouldn’t be lacking in any indictment. It was a quick journalism 101 course to explain that his very job was the thing on trial. “I work as a journalist and report on anything I consider that has news value. I am also remunerated per piece by the agency,” he said.

Alayumat, a 30-year-old reporter working for the shuttered pro-Kurdish outlet Dicle Medya News Agency (Dihaber), was detained on July 15, 2017, alongside a younger colleague, Nuri Akman, who was assigned by the agency to spend a week shadowing Alayumat to gain experience. After spending 13 days in custody, Alayumat was arrested for “procuring confidential state documents for political or military espionage purposes” and “membership in a terrorist organization” and sent to prison, while Akman was released on probation. During the first hearing, the court ruled that Alayumat would remain in detention, and maintained the probationary restrictions on Akman until the next hearing on 25 April.

The taboo of reporting on aid to Islamists in Syria

Prosecutors in Turkey have been presenting journalistic activities as terrorism for a long time, especially since authorities began prosecuting pro-Kurdish outlets as part of the “KCK press trial.” All of the outlets targeted have been closed by successive emergency decrees following a coup attempt in July 2016. Dihaber, founded after its predecessor DİHA was closed by emergency decree in October 2016, was itself was shut down in August 2017. Their successor, Mezopotamya Agency, continues to be targeted with access bans on its website and trials against many of its journalists.

The authorities’ decision to pursue journalists as spies is based on-the-fly definitions of what facts are illicit and harmful to the “security of the state”. While working in Hatay, a multicultural province that borders conflict-ridden parts of Syria, Alayumat had been reporting on allegations that supplies were sent to Islamist groups by Turkey’s intelligence agency, the National Intelligence Organization (MİT), as well as the construction of a wall on the Syrian border. Those reports and photographs – some of which were not even taken by him but downloaded from the Internet – have been presented by prosecutors as evidence of his “crime”.

“Erdoğan Alayumat’s detention is like the premise of the situation we are in today,” his lawyer Tugay Bek told Index on Censorship, referring to Turkey’s joint military operation with opposition fighters in Syria’s Afrin. “Alayumat was investigating how some of these groups [fighting in Syria] were trained and provided logistic supplies by the National Intelligence Organization. These claims, which were rumours and hard to assess back then, are today openly accepted without any need for concealment. They’re even saying to critics, ‘What is there to be against about?’ Alayumat was reporting on whether there was or not such a militia power. We are seeing today that there was,” Bek said.

Reporting on MİT’s activities have become taboo in the wake of the discovery of four trucks that were carrying weapons to Syria in January 2015. Far from denying allegations that the trucks belonged to MİT, the government said the weapons were destined for Turkmen groups fighting in Syria but that reporting the news represented a disclosure of state secrets. When footage and photos showing the content of the trucks were published a few months later by the daily Cumhuriyet, prosecutors were instructed to take strong action. The then-editor-in-chief, Can Dündar, was imprisoned along with Ankara bureau chief Erdem Gül. Dündar, who faces up to 25 years in jail on espionage charges for publishing the story, has been living in Germany since his release by a constitutional court decision, but would face arrest if he returns to Turkey.

Former journalist and main opposition Republican People’s party (CHP) lawmaker Enis Berberoğlu was sentenced to 25 years in prison last year for purportedly providing Cumhuriyet with the video that showed the weapons found in the trucks. The sentence was quashed by an appeals court, but Berberoğlu remains in detention during a retrial that began in December 2017.

In this context, Alayumat’s report on a storehouse which MİT was suspected of using to supply weapons by night and provide training to Syrian opposition groups by day represented high-risk coverage. However, for the charge of espionage to be valid, the prosecution must also show which groups benefited from the exclusive knowledge of the report, his lawyer said.

“If there is some sort of espionage, there should be a recipient. Although emails and WhatsApp messages are in the police’s possession, there is no evidence as to whom [this information] was sent to or where. [The prosecution] feels no need to prove the claims,” Bek said.

Alayumat told the court that everything he did was sent to a media organisation. He rejected the accusation that the photographs of the storehouse were to be used for espionage. “When you prepare a news report, you also need pictures. [People] brought me there, I took pictures and interviewed the people in the area. These pictures were taken for reporting,” he said.

He also complained about a serious factual mistakes in the indictment. The indictment alleged that he had joined “the youth structures of a terrorist organisation” during his university years, he said, indicating that this would have been impossible: “I left primary school in grade 4. I had to support my family. I finished primary school years later through distance education. As I didn’t have any university life, this statement is wrong.”

Police aim to beat murder confession out of young reporter

Reports that Alayumat was subject to ill-treatment and torture at a prison in the Mediterranean district of Tarsus made the news a few months after he was detained. His lawyer filed a complaint, upon which Alayumat was transferred to a prison on the opposite coast of the country. He was subject to diverse forms of punishment including solitary confinement and beatings, reports said.

Akman, a 23-year-old reporter who studies law at Dicle University in Diyarbakır, also suffered ill-treatment by police officers. His protests at his improper detention procedures and insistence at calling his lawyer were met with beatings, he said. “Nine-ten police officers battered me,” Akman said, adding that officers also forced him to admit that he killed two policemen in Hatay. “When I told them that I was an anti-militarist and against the killing of people, I was again subject to physical violence.” Akman said he was taken to a doctor for a medical report but brought back without being permitted to see the physician.

Akman, who despite some nerves before the hearing, smiled amiably and gave an impassioned defence to the court.

He said he intended to spend a week with Alayumat and earn a little money by doing reports. “There is an ongoing war on the other side of the border, so we wanted to report on how people living in bordering towns were affected,” he said, explaining that all the notes and pictures he took were intended for reporting. “I am studying law and I had to follow hundreds of cases when I worked as a judicial reporter in Diyarbakır over the course of one year. I am appalled by these accusations. I don’t accept them.”

To defend themselves, both Alayumat and Akman had to defend that their reporting was not a crime, which is the irony of the situation of journalism in Turkey. Journalists on trial face allegations which question the essence of their job. The expression “journalism is not a crime” has never been more significant for any other profession as it now is for journalism in Turkey.

“I have filed hundreds of reports,” Alayumat told the court. “If you can just look at them, you will see that they are nothing but news reports. What I have been doing is journalism.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1517838504081-b3f4f9d3-a9c1-8″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

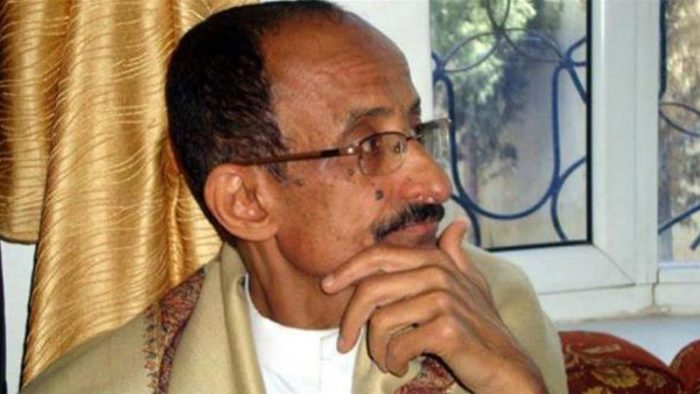

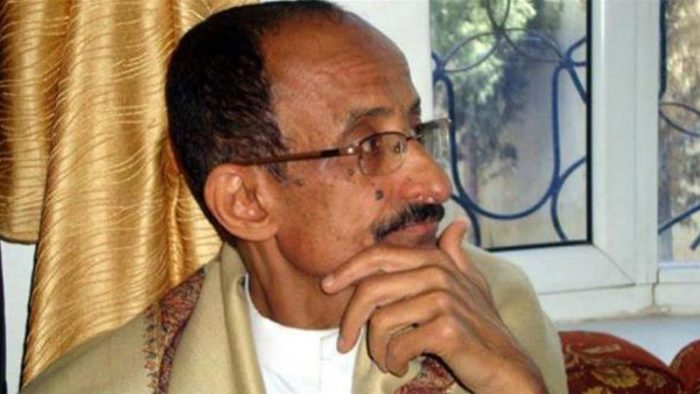

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Interpol 86th general assembly (Credit: Interpol)

Red notices have become a tool of political abuse by oppressive regimes. Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

“The use of the Interpol system to target journalists is a serious breach of media freedom. Interpol’s own constitution bars it from interventions that are political in nature. In all of these cases, the accusations against the journalists are politically motivated,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

In the most recent case on 21 October, journalist and blogger Zhanara Akhmet from Kazakhstan was detained in Ukraine on an Interpol warrant and is currently in a temporary detention facility. Akhmet claims this red notice is politically motivated.

The journalist worked for an opposition newspaper, the Tribune, in Kazakhstan as well as documented human rights violations by the Kazakh authorities on a blog.

On 14 October, also in Ukraine, Azerbaijani opposition journalist Fikret Huseynli was detained at Kyiv Boryspil Airport.

Huseynli sought refuge in the Netherlands in 2006 and was granted citizenship two years ago. While leaving Ukraine, the journalist was stopped by Interpol police with a red notice issued at the request of the Azerbaijani authorities. He has been charged with fraud and illegal border crossing.

Because Huseynli holds a Dutch passport, he cannot be forcibly extradited to Azerbaijan, but he told colleagues he fears attempts to abduct him.

“The arrest of the Azerbaijani opposition journalist by the Ukrainian authorities at the request of the authoritarian government of Azerbaijan is a serious blow to the common European values such as protection of freedom of expression, which Ukraine has committed itself to respect as part of its membership in the Council of Europe and the OSCE,” IRFS CEO Emin Huseynov said.

On 17 October, Boryspil City District Court ruled to imprison Huseynli for 18 days at a pre-trial detention centre, Huseynli’s lawyer announced.

Huseynli’s arrest was the second time in a month that a journalist has been detained in Ukraine on a red notice.

On 20 September, authorities detained journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov, who had been seeking political asylum in Ukraine, under an Interpol red notice when he arrived from Turkey with his family. Okhunjonov writes from exile for sites including BBC Uzbek on Uzbekistan’s authoritarian government. Uzbekistan filed the international arrest warrant for the journalist on fraud charges. He denies the charges against him.

Five days after he was detained, a Kyiv court sentenced Okhunjonov to a 40-day detention while they decide whether to extradite him to his home country. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F%23%2F|||”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Interpol warrants have also been issued in Spain.

Turkish journalist Doğan Akhanlı was detained while on vacation in Spain on 9 August. The journalist has lived in Cologne since 1992 where he writes about human rights issues, particularly the Armenian Genocide, which Turkey denies.

Turkey charged Akhanlı with armed robbery which supposedly occurred in 1989. After the charges were brought against him in 2010 and he was acquitted in 2011, the Supreme Court of Appeals overturned his acquittal and a re-trial began. Akhanlı faces “life without parole”.

Two weeks later, Interpol removed the warrant and Akhanlı was released. The decision was made after German chancellor Angela Merkel denounced the abuse of the Interpol police agency: “It is not right and I’m very glad that Spain has now released him. We must not misuse international organisations like Interpol for such purposes.”

Markel claimed Erdogan’s use of the international agency for political purposes was “unacceptable”.

Akhanlı’s detention came two weeks after Turkish journalist Hamza Yalçın was detained on 3 August at El Prat airport in Barcelona, where he was vacationing, Cumhuriyet reported. He holds a Swedish passport and has sought asylum there since 1984.

Yalçın is being accused of “insulting the Turkish president” and spreading “terror propaganda” for Odak magazine of which he was the chief columnist, according to a report by Evrensel.

Like Ukraine, Spain’s member state status in the Council of Europe also arises the question of their activity in the arrests of Akhanlı and Yalçın. “The latest cases of arrests of journalists in Ukraine and Spain on the basis of Interpol red notices … have extremely worrying implications for press freedom,” Rebecca Vincent UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders, said. “Interpol reform is long overdue, and is becoming increasingly urgent as critical journalists are now at risk travelling even in Council of Europe member states”.

Turkey’s recent continued persecution of journalists through Interpol also reached as far as Germany. A Turkish prosecutor has requested the Turkish government issue a red notice through Interpol though it is unclear if it went through.

On 28 September 2017, the Diyarbakir Prosecutor’s Office filed an application to seek an Interpol red notice for Can Dündar, the former Editor-in-chief of Turkey’s anti-regime newspaper, Cumhuriyet. The demand for a red notice is based on a speech made by Dündar in April 2016, supposedly supporting the “terror propaganda” of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Dündar fled Turkey for Germany in 2016.

On the same day, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) nominated Dündar and the Cumhuriyet newspaper for the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Turkey is no exception to using this system just as is Russia, Iran, Syria, and its close neighbour and ally Azerbaijan among other governments, where political direction does not necessarily align with democracy, respect for human rights and basic freedoms,” Arzu Geybulla, an Azerbaijani journalist and human rights activist said. “Targeting its citizens who have escaped persecution and have been forced to flee as a result of their opinions, is a worrying sign especially at a time, when over 160 journalists are currently behind bars in Turkey and thousands of people have lost their jobs, been arrested or currently face trials in the aftermath of the July coup.”

Although PACE has adopted a resolution condemning the abuses of Interpol red notices, a review of Interpol’s red notice procedure has yet to be adopted. Amid criticism from human rights activists, journalists, and even leaders like Angela Merkel, it is unclear if Interpol will make a change to their red notice regulations.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1509034712367-374920af-c5df-6″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]