25 Jul 2016 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Nazlı Ilıcak

A “ping” woke me in early hours of Monday morning. It was a message from a colleague reading: “Signs of a crackdown. Arrest warrant for Nazlı Ilıcak is issued, she is being searched.”

This was the witch hunt that many critical journalists who belong to the shrinking independent media dreaded for days.

Ilıcak is a 72-year-old veteran journalist. A fiercely defiant figure who belongs to the centre-right and liberal flank of the media, she had just lost her column in the liberal daily, Özgür Düşünce, which was forced to close last week under immense legal and financial pressure.

I rushed out of bed to contact lawyers pursuing the cases, like the one about Orhan Kemal Cengiz, an internationally respected columnist, lawyer and human rights activist, who was conditionally released on Sunday with a ban on travelling abroad.

Soon we had been informed about a list of 42 journalists who have all been targeted with arrest orders on the basis of being part of the “media leg of terrorist organisation FETO” and by implication part of the Gülen Movement.

Reminiscent of Thomas Hobbes’s aphorism, “homo homini lupus” (“man is wolf to man”), some well-placed journalists were busy – like a certain popular columnist with Hürriyet daily – joining the chorus in support for their arrest.

The manhunt was unleashed early and at the time of writing, at least 19 of them were either seized or had surrendered. Ilıcak’s whereabouts were unknown. Eleven of the journalists on the list are believed to be abroad.

The list is a curious one. For us veteran journalists it contains a blend of good colleagues and bold reporters, who were busy breaking story after story on corruption, abuses of power and the deterioration of Turkey’s democratic order.

Büşra Erdal, who wrote for the now-closed Zaman Daily, was one of the best reporters covering the judiciary and court cases; Cihan Acar was known for relentlessly scrutinising stories in the now shuttered Bugün daily and later in Özgür Düşünce. They were long targeted as Gülen sympathisers but what mattered for journalism was their contribution to it.

Another, Bülent Mumay, was recently fired from Hürriyet. Staunchly secular, he ran the internet edition of the large daily, and it was his endless questioning of the government via Twitter that, he says, led to his unemployment. Perhaps not so surprisingly, he was quick to post a photo of his press card on Facebook, issued by Turkish Journalists’ Association (TGC), saying: “This is the only organisation I belong to. I know of no other; I know of no other profession. I shall now go the prosecutor’s office to tell this.”

Another one was Fatih Yağmur, a brilliant young reporter who was the first to break the story in March 2014 of the Turkish Secret Service lorries that allegedly carried weaponry to Syrian jihadists months before daily the Cumhuriyet, whose editor Can Dündar was sentenced to five years and ten months in prison.

Yağmur was soon after fired from Radikal daily, a part of Doğan Media Group, without any specific explanation.

The Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), of which I am a co-founder, has awarded Yağmur with the European Union Investigative Journalism Award last year. He was proud to be recognised after the humiliation of being left unemployed for doing his job properly.

Soon after the manhunt began, Fatih tweeted: “I hear that arrest order was issued on me. It was obviously not enough to punish me with unemployment. I am now shutting down my telephone etc. I shall not surrender until the Emergency Rule is over.”

We also found out that Ercan Gün, news editor of Rupert Murdoch-owned Fox TV, was on the list. His friends said he was on his way to Istanbul to surrender. Gün tweeted: “I trust the law, even if under Emergency Rule.”

With the traffic of those hunted, it was apparent that they believed a certain motive behind the arrests. Ufuk Şanlı, who had earlier worked with Zaman and after (the now a staunch pro-AKP daily) Sabah, tweeted: “I understand that the arrests were issued about journalists who covered and commented about the graft probes (about Erdoğan and the AKP top echelons) in 17-25 December. Thus, my name too.”

He added: “I’ve been a journalist for 15 years, and unemployed for 10 months. I want everybody to know that I have not been in anything but journalism all this time. I believe in democracy, and please pay attention to anything else [said].”

Indeed, the curious mix about the list is telling: instead of a core of columnists, keen reporters, which is the backbone of journalism, stand out. So, informing part of our profession is automatically dealt another severe blow.

This is now the time to raise the SOS flag to all our good colleagues in democratic countries. Unless given clearly articulated assurances about media freedom, the ongoing crackdown will remain a fact. The entire journalist community and international organisations should be acting with a maximum focus on the developments.

All the independent journalists of Turkey who fear the worst, I’m afraid, are justified to do so.

The 42 journalists targetted with arrest orders are: Abdullah Abdulkadiroğlu, Abdullah Kılıç, Ahmet Dönmez, Ali Akkuş, Arda Akın, Nazlı Ilıcak, Bayram Kaya, Bilal Şahin, Bülent Ceyhan, Bülent Mumay, Bünyamin Köseli, Cemal Azmi Kalyoncu, Cevheri Güven, Cihan Acar, Cuma Ulus, Emre Soncan, Ercan Gün, Erkan Akkuş, Ertuğrul Erbaş, Fatih Akalan, Fatih Yağmur, Habib Güler, Hanım Büşra Erdal, Haşim Söylemez, Hüseyin Aydın, İbrahim Balta, Kamil Maman, Kerim Gün, Levent Kenes, Mahmut Hazar, Mehmet Gündem, Metin Yıkar, Muhammet Fatih Uğur, Mustafa Erkan Acar, Mürsel Genç, Selahattin Sevi, Seyit Kılıç, Turan Görüryılmaz, Ufuk Şanlı, Ufuk Emin Köroğlu, Yakup Sağlam, Yakup Çetin.

But it was not just the press that have reason to fear the aftermath of the coup.

The number of arrests nationawide has approached 15,000 while 70,000 people have been purged within the state apparatus and academia. According to Erdogan’s statement late Saturday night, out of 125 generals arrested, 119 have been detained. The number of lower ranked officers and soldiers rounded up stands at 8,363.

Out of the 2,101 judges and prosecutors arrested, 1,559 are in detention as well as 1,485 police officers and 52 top local governors. Fifteen universities, 35 hospitals, 104 foundations, 1,125 NGOs and 19 trade unions have been shut down, based on the allegations that they all belong to a “parallel structure”, namely the Gülen Movement.

The largest union of judges and prosecutors, YARSAV, whose inclination is left and secular, has been shut down indefinitely. The country’s largest charity group, Kimse Yok Mu, which has a vast network of hospitals and orphanages across Africa and Asia, has also been closed.

All this official data speaks for itself, exposing the magnitude of the “counter wave”.

It raises huge questions for any decent journalist. We would be led to believe that Turkey’s arrested generals – a third of the country’s 347 – are Gülenists. But this doesn’t look at all convincing among political circles in the US capital, according to Hürriyet’s Washington correspondent Tolga Tanış.

What’s perhaps more worrisome is that given the coup attempt, the arrests and the incredible implosion, Turkey’s defence system is in huge crisis, leaving the country very vulnerable to hostile activity, in particular by IS units.

Then, of course, there is the widespread confusion over key institutions such as schools and hospitals being shut down. There is no clarity about the fate of the students and patients.

The emergency rule has sent chills deep into the intellectual and traditionally dissenting elite of Turkey. So far, there has been absolutely no assurance from Erdogan or prime minister Binali Yıldırım that the freedom and rights of those in the media, academia, civil society organisations and political opposition groups will be respected.

On the contrary, an arrest order was issued for 19 local journalists in Ankara. A young reporter with ETHA news agency, Ezgi Özer, was arrested in Dersim province. The rector of Dicle University in Diyarbakır, Ayşegül Jale Saraç was detained as well.

Not so surprisingly, then, there is a widespread mistrust and fear spreading now into the intellectual community in Turkey about what they see as an indiscriminate crackdown.

As my colleague Can Dündar put it in the Guardian on Friday: “‘Fine, we are rid of a military coup, but who is to shelter us from a police state? Fine, we sent the military back to their barracks, but how are we to save a politics lodged in the mosques?”

“And the question goes to a Europe preoccupied with its own troubles: will you turn a blind eye yet again and co-operate because ‘Erdogan holds the keys to the refugees’? Or will you be ashamed of the outcome of your support, and stand with modern Turkey?” Dündar added.

I agree with him and let me add a key point: if this oppressive trend continues with full force members of the media, academia, and civil society, as well as the young and secular who feel victimised and desperate due to the vicious cultural struggle that has been going on for years, will have no choice but emigrate. Europe and the West should brace themselves for this scenario.

Turkey is cracking under its incurable divisions.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

18 Jul 2016 | Africa, Magazine, mobile, South Africa

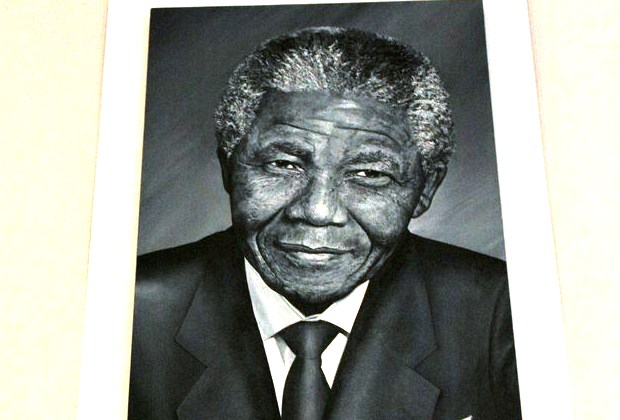

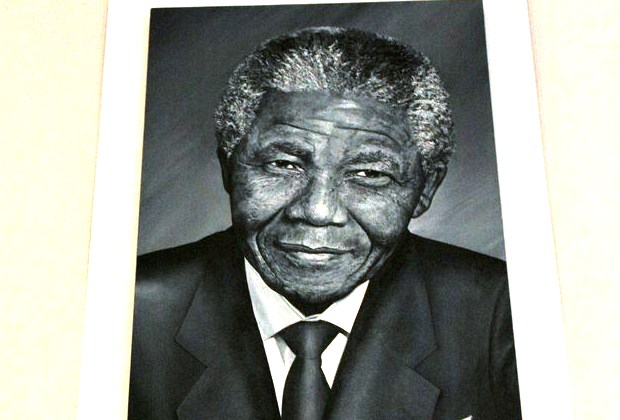

Index has released a special collection of apartheid-era articles from the Index on Censorship magazine archives to celebrate Nelson Mandela day 2016. Holly Raiborn has selected the collection, tracing the breadth of writing during the apartheid era from authors both in the country and in exile. The articles selected trace the history of this period in South Africa’s history. Significant South African writers, including Nadine Gordimer, Don Mattera, Pieter-Dirk Uys and Desmond Tutu, discuss the impacts this era of oppression had on themselves, their peers and their country. The collection will now form a reading list available to students who are researching the apartheid years, and will be available via Sage Publishing in university libraries.

Before 1948 “apartheid” was just a word in Afrikaans with a simple meaning: separateness. However, over the course of the next 50 years, the word “apartheid” would take on a new level of significance. The connotation of the word grew darker with every dissident banned, prisoner tortured, child left uneducated and home destroyed. Apartheid is no longer just a word; it carries the history of brutality, censorship and maltreatment of South Africans. For a limited period, Index and Sage are making the collection free to non-subscribers. For those who want to study the history of censorship further, Index on Censorship magazine’s archives are held at the Bishopsgate Institute in London and are free to visit.

Nadine Gordimer, Apartheid and “The Primary Homeland”

1972; vol. 1, 3-4: pp. 25-29

An address regarding the 1972 plans of the South African government to abolish the right of appeal against decisions brought by the State Publications Control Board, effectively ridding writers of a means to combat the rulings of government-appointed censors. The censorship in South Africa at this time caused a breakdown in communication between “the sections of a people carved up into categories of colour and language.”

Frene Ginwala, The press in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 3: pp. 27-43

An extensive report on the state of the “free” press in South Africa prepared for the United Nations’ Unit on Apartheid in November 1972. Ginwala posits that apartheid attempts to segregate freedom and this attempt “extinguishes freedom itself”.

Robert Royston, A tiny, unheard voice: The writer in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 4: pp. 85-88

A personal narrative reflecting the experiences of Robert Royston as a black poet in South Africa during a period of popularity for black poetry amongst white readers. Royston describes a disconnect between the language he speaks and the language understood by the government and white citizens, although they technically share the same tongue.

Jack Slater, South African Boycott: Helping to enforce apartheid?

1975; vol. 4, 4: pp. 32-34

An article by a New York Sunday Times staff writer arguing that the proposed cultural boycott would ultimately negatively affect black South Africans more than white South Africans who were merely irritated. Slater feared black South Africans suffer from feelings of isolation from the outside world because of the cultural boycott.

Benjamin Pogrund, The South African press

1976; vol. 5, 3: pp. 10-16

A discussion regarding the often contradictory aspects of the South African “free” press in which newspapers censor themselves. Strict laws preventing communism, sabotage and terrorism were often twisted to prevent the publications of black viewpoints.

John Laurence, Censorship by skin colour

1977; vol. 6, 2: pp. 40-43

In the UK in the 1970s, news about South Africa was contributed by the white minority while black South Africans were not interviewed by major European news outlets about events predominantly affecting their community such as the Soweto riots. This article discusses the clear racial bias, blaming it for the misinformation and misconceptions in Europe about apartheid-era South Africa.

Brief reports: Bad days in Bedlam

1978; vol. 7, 1: pp. 52-54

A report regarding the glaring health violations within the overwhelmingly black South African mental hospitals that were largely ignored due to racial factors and censorship brought about with the 1959 Prisons Act. This act made reporting “false information” on prisons or prisoners punishable with jail time or fines which led to prison and mental patient camp, conditions being largely neglected in the media.

Robert Birley, End of the road for “Bandwagon”

1978; vol. 7, 2: pp. 6-8

An article about a significant yet short-lived South African journal, Bandwagon, whose purpose was to unite individuals banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. The act featured strictly enforced limits on social life and essentially made any meetings, social or otherwise, illegal for a banned person; therefore, the impact and importance of this publication should not be understated.

William A. Hachten, Black journalists under apartheid

1979; vol. 8, 3: pp. 43-48

Hachten discusses the new found power of being a black journalist (the literacy rate of black South Africans had recently surpassed whites) and the growing hazards of the profession in the late 1970s. Journalists were arrested for reporting the events of the Soweto riots and faced constant police and legislative pressure on top of fines and censorship imposed by the white-controlled newspapers they had no choice but to work for.

Don Mattera, Open Letter to South African whites

1980; vol. 9, 1: pp. 49-50

An address from a banned poet who pointed out the cruelty of white South African society so that they may never claim ignorance to the atrocities. He questions why his words are deemed so dangerous that he is not allowed to attend social gatherings like birthdays and funerals

Nadine Gordimer, The South African censor: No change

1981; vol. 10, 1: pp 4-9

Gordimer hypothesised that the successful appeal of her novel’s banning, and that of many novels by other white writers, was due to the fact that she is white. She argued that South Africa would never be rid of censorship until it was rid of apartheid.

Donald Woods, South Africa: Black editors out

1981; vol. 10, 3: pp. 32-34

Woods wrote about the shift from editors of South African newspapers facing fines for disobeying censorship statutes to jail time in the late 1970s and explained that this shift signalled that dissent and bold writing was permitted in white politics but would not be permitted from black perspectives. He argued that the reason the government did not censor the press entirely was because they enjoyed the façade of a “free press” and there was no reason for them to need full censorship.

Keyan Tomaselli, Siege mentality: A view of film censorship

1981; vol. 10, 4: pp. 35-37

Tomaseli explained that censorship was often as financially driven as it is culturally. He wrote that censorship interferes at three stages, namely during: finance, distribution and through state censorship law. Tomaseli expands on the circumstances that led to many different films being banned or harshly edited.

Mbulelo Vizikhungo Mzamane, No place for the African: South Africa’s education system, meant to bolster apartheid, may destroy it

1981; vol. 10, 5: pp. 7-9

Mzamane claimed that the Bantu Education Act of 1956 was clearly a ploy to create compliant Africans within a society increasingly controlled by Afrikaners. Bantu schools were essentially vocational training for servitude to whites and textbooks were blatant indoctrination, he argued.

Christopher Hope, Visible Jailers: A South African writer casts a humorous eye over the bannings by his country’s censors between 1979 and 1981

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 8-10

A clever take on the South African censor. Hope addresses the reasons and methodology of the South African censor with tongue and cheek commentary as he reviews the Publications Appeal Board: Digest of Decisions. This collection is comprised of the totality of decisions made by the South African Publications Appeal Board.

Sipho Sepamla, The price of being a writer

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 15-16

Sepamla writes about the struggles of continuing to write under such strict scrutiny by censors after the banning of his latest novel, A Ride on the Whirlwind. He speaks of the disenchantment experienced by any writer that has faced censorship and specifically black South African writers who faced this treatment all too often.

Barry Gilder, Finding new ways to bypass censors: How apartheid affects music in South Africa

1983; vol. 12, 1: pp. 18-22

Music was divided along race and class lines. Music was banned under the Publications Act if it was found to be unsafe to the state, harmful to the relationship between members of any sections of society, blasphemous, or obscene Songs with even symbolic mention of freedom or revolution were banned.

Barney Pityana, Black theology and the struggle for liberation

1983; vol. 12, 5: pp. 29-31

Reverend Pityana wrote of the paradox that Christianity teaches that all are equal under god but the church in South Africa still degraded and segregated. He writes that The Bible teaches that all are created in God’s image and the plight of the Jews and other marginalised groups within the Bible give hope, guidance and reassurance to those suffering under apartheid.

Miriam Tlali, Remove the chains: South African censorship and the black writer

1984; vol. 13, 6: pp. 22-26

Tlali, a black female South African novelist, addresses the added difficulties of being black and a woman in Afrikaner-controlled society. She speaks both from personal experience and about the struggles of her peers.

Johannes Rantete, The third day of September

1985; vol. 14, 3: pp. 37-42

An honest first-hand account of the Soweto riots by a 20-year-old unemployed black South African. Rantete wrote a sympathetic eyewitness report of the September riot and the first reaction of the South African authorities to confiscate and ban it.

Alan Paton, The intimidators

1986; vol. 15, 1: pp. 6-7

The white South African novelist on the intimidation tactics and stalking committed by the security police after his controversial novel, Cry, The Beloved Country, was published. He notes that he suspects his treatment would have been even worse had he been black.

Anthony Hazlitt Heard, How I was fired

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 9-12

Former editor of the Cape Times, who was awarded the International Federation of Newspaper Publishers’ Golden Pen of Freedom in 1986, Heard was dismissed from his position after his interview with banned leader of the African National Congress Oliver Tambo. Heard speaks about 16 years of editing under apartheid and the circumstances surrounding his dismissal in August 1987.

Anton Harber, Even bigger scissors

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 13-14

‘The importance of international pressure in giving a measure of protection to the South African press cannot be overestimated’ wrote the co-editor of the Johannesburg Weekly Mail in this assessment of Botha’s policy towards the alternative press. Harber offered a compelling plea for protection of the South African alternative press by the international media.

Jo-Anne Collinge, Herbert Mabuza, Glenn Moss and David Niddrie, What the papers don’t say

1988; vol. 17, 3: pp. 27-36

An extensive review of restrictions in South Africa at that time including the Defence Act, Police Act, Prisons Act, Internal Security Act and the Publications Act. The writers offer suggestions for the safety and protection of journalists in the future.

Richard Rive, How the racial situation affects my work

1988; vol. 17, 5: pp 97-98, 103

Rive discusses the racial factors that have contributed to his writing style and the works of any black writer in South Africa. He emphasises the hypocrisy of the society he lives in which will criticise black writers as simplistic but not allow quality education and where the books of black writers sitting in libraries that they are not allowed to enter.

Albie Sachs, The gentle revenge at the end of apartheid

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 3-8

Albie Sachs was asked by Index on Censorship to look ahead to constitutional reform that was not foreseeable at that point and how to enshrine freedom of expression in a post-apartheid South Africa. Four months later came the unbanning of the ANC on 2 February, the release of Nelson Mandela on 11 February and his reunion with Oliver Tambo in Sweden on 12 March, all of which promised real change. These are extracts from the conversation about a future South Africa. He offers suggestions for the then-looming transition from apartheid to democracy.

Oliver Tambo, We will be in Pretoria soon

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 7

In May 1986 Oliver Tambo, president of the African National Congress, was interviewed by Andrew Graham. The ANC president discussed the beginning of the end for apartheid and traces the lineage of the racism that fuelled the apartheid for nearly 50 years. Tambo optimistically plans for a new reign of government made up of representation that actually reflects the populous.

Nadine Gordimer, Censorship and its aftermath

1990; vol. 19, 7: pp. 14-16

On 11 July 1979, Nadine Gordimer’s novel Burger’s Daughter was banned by the South African directorate of publications on the grounds – among others – that the book was a threat to state security. After an international outcry the director of publications appealed against the decision of his own censorship committee to the publications’ appeal board. In this article, Nadine Gordimer reflects on these events, and on the new censorship policy they heralded. Gordimer reflects on censorship under previous administrations and what she expects from President FW de Klerk’s reign as president.

Nadine Gordimer, Act two: one year later

1995; vol. 24, 3: pp. 114-117

A reflection on how far South Africa had come and still had to go by this frequently banned author. Using the Descartes method, Gordimer considers the role reversal that has occurred in post-apartheid South Africa as her once banned colleagues ascend to political power.

Desmond Tutu, Healing a nation

1996; vol. 25, 5: pp. 38-43

An Index interview with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Tutu discusses the urgency of healing the past before South Africa can truly move on to a brighter future. This brighter future was to be achieved with the aid of the Truth Commission. He argued that only honesty, compassion and forgiveness would lead to national unity in South Africa, even if that means prosecuting former ANC members. He stresses that the commission’s goal is reparations and not compensation.

Pieter-Dirk Uys, The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but…

1996; v0l. 25, 5: pp. 46-47

Famed satirist Pieter-Dirk Uys questioned if information about the atrocities of the apartheid could actually be uncovered by the Truth Commission. Uys asked how the country could heal when so many willing participants in the apartheid already seemed eager to forget or to forge their own accounts of history to avoid blame. His pessimistic view contrasted with that of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s.

All articles from Index on Censorship magazine, from 1972 to 2016, are available via Sage in most university libraries. More information about subscribing to the magazine in print or digitally here.

22 Jun 2016 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

From left, Ahmet Nesin (journalist and author), Şebnem Korur Fincancı (President of Turkey Human Rights Foundation) and Erol Önderoğlu (journalist at Bianet and RSF Turkey correspondent). (Photo: © Bianet)

I have known Erol Önderoğlu for ages. This gentle soul has been monitoring the ever-volatile state of Turkish journalism more regularly than anybody else. His memory, as the national representative of the Reporters Without Borders, has been a prime source of reference for what we ought to know about the state of media freedom and independence.

On 20 June, perhaps not so surprisingly, we all witnessed Erol being sent to pre-trial detention, taken out of the courtroom in Istanbul in handcuffs.

Charge? “Terrorist propaganda.” Why? Erol was subjected to a legal investigation together with two prominent intellectuals, author Ahmet Nesin, and Prof Şebnem Korur Fincanci – who is the chairwoman of the Turkish Human Rights Foundation – because they had joined a so-called solidarity vigil, as an “editor for a day”, at the pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem daily, which has has been under immense pressure lately.

This vigil had assembled, since 3 May, more than 40 intellectuals, 37 of whom have now been probed for the same charges. One can now only imagine the magnitude of a crackdown underway if the courts copy-paste detention decisions to all of them, which is not that unlikely.

Journalism has, without the slightest doubt, become the most risky and endangered profession in Turkey. Journalism is essential to any democracy. It’s demise will mean the end of democracy.

Turkey is now a country — paradoxically a negotiating partner with the EU on membership — where journalism is criminalised, where its exercise equates to taking a walk on a legal, political and social minefield.

“May God bless the hands of all those who beat these so-called journalists” tweeted Sait Turgut, a top local figure of AKP in Midyat, where a bomb attack on 8 June by the PKK had claimed 5 lives and left more than 50 people wounded.

Three journalists – Hatice Kamer, Mahmut Bozarslan and Sertaç Kayar – had come to town to cover the event. Soon they had found themselves surrounded by a mob and barely survived a lynch attempt.

Most recently, Can Erzincan TV, a liberal-independent channel with tiny financial resources but a strong critical content, was told by the board of TurkSat that it will be dropped from the service due to “terrorist propaganda”. Why? Because some of the commentators, who are allowed to express their opinions, are perceived as affiliated with the Gülen Movement, which has been declared a terrorist organisation by president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

It is commonplace for AKP officials from top down demonise journalists this way. Harrassment, censorship, criminal charges and arrests are now routine.

Detention of the three top human rights figures, the event in Midyat or the case of Can Erzincan TV are only snapshots of an ongoing oppression mainly aimed at exterminating the fourth estate as we know it. According to Mapping Media Freedom, there have been over 60 verified violations of press freedom since 1 January 2016.

The lethal cycle to our profession approaches its completion.

While journalists in Turkey – be they Turkish, Kurdish or foreign – feel less and less secure, the absence of truthful, accurate, critical reporting has become a norm. Covering stories such as the ”Panama Papers” leak — which includes hundreds of Turkish business people, many of whom have ties with the AKP government — or the emerging corruption case of Reza Zarrab — an Iranian businessman who was closely connected with the top echelons of the AKP — seems unthinkable due to dense self-censorship.

Demonisation of the Kurdish Political Movement and the restrictions in the south eastern region has made it an extreme challenge to report objectively on the tragic events unfolding in the mainly Kurdish provinces which have forced, according to Amnesty International, around 500,000 to leave their homes.

Journalism in Turkey now means being compromised in the newsrooms, facing jail sentences for reportage or commentary, living under constant threat of being fired, operating under threats and harassment. A noble profession has turned into a curse.

In the case of Turkey, fewer and fewer people are left with any doubt about the concentration of power. It’s in the hands of a single person who claims supremacy before all state institutions. The state of its media is now one without any editorial independence and diversity of thought.

President Erdoğan, copying like-minded leaders such as Fujimori, Chavez, Maduro, Aliyev and, especially, Putin, did actually much better than those.

His dismay with critical journalism surfaced fully from 2010 on, when he was left unchecked at the top of his party, alienating other founding fathers like Abdullah Gül, Ali Babacan and others who did not have an issue with a diverse press.

Soon it turned into contempt, hatred, grudge and revenge.

He obviously thought that a series of election victories gave him legitimacy to launch a full-scale power grab that necessitated capturing control of the large-scale media outlets.

His multi-layered media strategy began with Gezi Park protests in 2013 and fully exposed his autocratic intentions.

While his loyal media groups helped polarise the society, Erdoğan stiffly micro-managed the media moguls with a non-AKP background — whose existence depended on lucrative public contracts — to exert constant self-censorship in their news outlets, which due to their greed they willingly did.

This pattern proved to be successful. Newsrooms abandoned all critical content. What’s more, sackings and removals of dignified journalists peaked en masse, amounting now to approximately 4,000.

By the end of 2014, Erdoğan had conquered the bulk of the critical media.

Since 2015 there has been more drama. The attacks against the remaining part of the critical media escalated in three ways: intimidation, seizure and pressure of pro-Kurdish outlets.

Doğan group, the largest in the sector, was intimidated by pro-AKP vandalism last summer and brought to its knees by legal processes on alleged “organized crime” charges involving its boss.

As a result the journalism sector has had its teeth pulled out.

Meanwhile, police raided and seized the critical and influential Koza-Ipek and Zaman media groups, within the last 8 months, terminating some of its outlets, turning some others pro-government overnight and, after appointing trustees, firing more than 1,500 journalists.

Kurdish media, at the same time, became a prime target as the conflict grew and more and more Kurdish journalists found themselves in jail.

With up to 90% of a genetically modified media directly or indirectly under the control Erdoğan and in service of his drive for more power, decent journalism is left to a couple of minor TV channels and a handful newspapers with extremely low circulations.

With 32 journalists in prison and its fall in international press freedom indexes continuing to new all-time lows, Turkey’s public has been stripped of its right to know and cut off from its right to debate.

Journalism gagged means not only an end to the country’s democratic transition, but also all bridges of communication with its allies collapsing into darkness.

A version of this article originally appeared in Süddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

24 May 2016 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia, Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, France, Germany, Greece, Index Reports, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland, Serbia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine

Mapping Media Freedom launched to the public on 24 May 2014 to monitor media censorship and press freedom violations throughout Europe. Two years on, the platform has verified over 1,800 media violations.

“The data the platform has collected over the last two years confirms that the state of press freedom across Europe is deplorable,” said Hannah Machlin, project officer for Mapping Media Freedom. “Media violations are occurring regularly in countries with strong democratic institutions and protective laws for journalists. Legislation limiting the press, violence across the continent and authoritarian governments are also fuelling this rapid and worrying decline. We hope that institutions and leaders take note of this information and take action swiftly.”

To mark the anniversary, we asked our correspondents to pick a key violation that stood out to them as an example of the wider picture in their region.

Russia / 113 verified reports

Several journalists and human rights activists attacked in Ingushetia

“The brutal attack on a minibus carrying six journalists and several human rights activists near the border between Ingushetia and Chechnya on the 9 March 2016 demonstrates the dangers faced by media professionals working in Russia’s North Caucasus. No suspects have been established so far. This case stands out due to its extreme violence but also supports a common trend: the reluctance of the local authorities to ensure that the journalists’ rights are respected.” – Ekaterina Buchneva

Italy / 190 verified reports

97 journalists accused of breaking the law in mafia investigation

“This was a very relevant investigation, with no precedent, that took place in October, a few weeks away from the start of the trial known as Mafia Capitale, which concerns the scandal that involved the government of the city of Rome. It is a collective intimidation because it involved 97 journalists, who were denounced for violating the secret on the ongoing investigations. It is a really serious form of intimidation because it was activated within the field of law and thus is not punishable.” – Rossella Ricchiuti

Turkey / 57 verified reports

Zaman newspaper seized by authorities

“These attacks and actions taken by the government against independent media in Turkey attest to the shrinking space of independent media overall. In addition, it illustrates the shifting power dynamic within the ruling government in Turkey where once upon a time friends, are turned into enemies by the regime. As the paper wrote itself, Turkey is headed through its ‘darkest and gloomiest days in terms of freedom of the press.'” – MMF’s Turkey correspondent

Azerbaijan/ 5 verified reports

Writer banned from leaving country

“Aylisl’s 12-hour interrogation at the airport and later charges of hooliganism were just as absurd as the claim that a 79-year-old man, suffering from a heart condition and other health issues would attack an airport employee to such an extent that it would cause hemorrhage. I chose this example to illustrate the absurdity of charges brought against individuals in Azerbaijan but also the extent to which the regime is ready to go in order to muzzle those voices who different.” – MMF’s Azerbaijan correspondent

Macedonia / 59 verified reports

Deputy Prime Minister attacks journalist

“This incident best demonstrates the division in society as a whole and among journalists as a professional guild. This is a clear example of how politicians and elites look upon and treat the journalist that are critical towards their policies and question their authority.” – Ilcho Cvetanoski

Bosnia / 56 verified reports

Police raid Klix.ba offices

“This was the most serious incident over the last two years in Bosnia regarding the state’s misuse of institutions to gag free media and suppress investigative journalism. In this specific incident, the state used its mechanisms to breach media freedoms and send a chilling message to all other media.” – Ilcho Cvetanoski

Croatia / 64 verified reports

Journalist threatened by disbanded far-right military group

“After the centre-right government in Croatia came to power in late 2015, media freedom in the country rapidly deteriorated. Since then around 70 media workers in the public broadcaster were replaced or removed from their posts. This particular case of the prominent editor-in-chief of the weekly newspaper Novosti receiving a threatening letter from anonymous disbanded military organisation demonstrates the polarisation in the society and its affect on media freedom.” – Ilcho Cvetanoski

Greece / 34 verified reports

Golden Dawn members assault journalists covering demonstration

“This was the second attack against journalists by Golden Dawn members within one month. With more than 50,000 asylum seekers and migrants trapped in Greece, the tension between members of the far-right group and anti-fascist organisations is rising.” – Christina Vasilaki

Poland / 35 verified reports

Over 100 journalists lose jobs at public broadcasters

“This report highlights the extent of the ongoing political cleansing of the public media since the new media law was passed in early January.” – Martha Otwinowski

Germany / 74 verified reports

Journalist stops blogging after threats from right-wing extremists

“The MMF platform lists numerous incidents where German journalists have been threatened or physically assaulted by right-wing extremists over the last two years. This incident stands out as a case of severe intimidation that resulted in silencing the journalist altogether.” – Martha Otwinowski

Belgium / 19 verified reports

Press asked to respect lockdown during anti-terrorism raids

“On 22 November 2015, the Belgian authorities asked the press to refrain from reporting while a big anti-terrorist raid was taking place in Brussels. While understandable, this media lock-down raised questions for press freedom and underlined the difficulties of reporting on terror attacks and anti-terror operations.” – Valeria Costa-Kostritsky

Luxembourg / 2 verified reports

Investigative journalist on trial for revealing Luxleaks scandal

“This Luxleaks-related case is the only violation we have become aware in Luxembourg over the period (which is not to say that no other cases occurred). Along with two whistleblowers, a journalist was prosecuted by PricewaterhouseCoopers and accused of manipulating a whistleblower into leaking documents. This is a good example of the threat the notion of trade secrets can represent to journalism.” – Valeria Costa-Kostritsky

Ukraine / 127 verified reports

Website leaks personal information of more than 4,000 journalists

“This incident shows how fragile the media freedom and personal data of journalists are in armed conflict. Even after a great international scandal, the site continues to break the legislation and publishes new lists. It has been operating for two years already and those involved in its activities go unpunished. It seems that the post-Maidan Ukraine has simply ‘no political will’ for this.” – Tetiana Pechonchyk

Crimea / 18 verified reports

Journalists’ homes searched, criminal case filed

“This report shows the everyday life of independent journalists working on the peninsula. Only a few critical voices are still remaining in Crimea while the majority of independent journalists were forced to leave the profession or to leave Crimea and continue their work on the mainland Ukraine.” – Tetiana Pechonchyk

Spain / 49 verified reports

Journalist fined for publishing photos of arrest

“The latest issue for the Spanish media is the Public Security Law, introduced in June 2015, which among other things limits space for reporters. The law prohibits the publication of photo and video material where police officers may be identified, unless official state permission is obtained. This was the first case of a journalist being fined by the new law.” – Miho Dobrasin

Belarus / 47 verified reports

Journalist beaten by police, detained and fined for filming police attacks

“The story has ended in impunity: a criminal case was not even filed against the police officers who had beaten the journalist.” – Volha Siakhovich

Latvia / 12 verified reports

Latvia and Lithuania ban Russian-language TV channels

“This was the beginning of a disturbing tendency to react with rather futile gestures against Russian television channels. The bans are not so much against the media, as telling the audience that the authorities, not the public, will decide what Latvian viewers may or may not see or hear.” – Juris Kaža

Serbia / 110 verified reports

Investigative journalists victim of smear campaign

“You have to be very brave to launch a new investigative journalism portal in Serbia and expose corruption and organised crime involving government officials. That is why the launch of KRIK in early 2015 has been so important for media freedom, but at the same time so dangerous for its journalists. Smear campaigns like this by pro-government tabloid Informer are a relatively new but common method in the Balkans to scare journalists off.” – Mitra Nazar