5 Feb 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala has been banned from entering the UK. The French comedian has long been a controversial figure in his home country, but he became internationally known when West Bromwich Albion striker Nicolas Anelka celebrated a goal with the now infamous quenelle — a sort of inverted nazi salute created by Dieudonné, his friend.

Dieudonné argues he is simply standing up to the establishment, and that the quenelle is an anti-establishment gesture. The facts tell a different story. He has made a number of clearly antisemitic comments, and has been convicted in France of inciting racial hatred.

Dieudonné was set to visit the UK to support Anelka, who has been charged by the Football Association over the incident, and faces a minimum five-match ban. As a colleague pointed out, it’s unclear how, exactly, further links to Dieudonné would help Anelka, but that is now beside the point, as he has been “excluded from the UK at the direction of the Secretary of State”. A letter from the Home Office, obtained by Swiss newspaper Tages-Anzeiger, states that he should not be allowed to board carriers to the UK. If he gets as far as the border, he’ll be turned away at the door, as it were.

But Dieudonné is not alone. Over the years, a number of controversial speakers, covering pretty much the entire spectrum of extremist ideologies, have been banned from entering the UK. The reasons given from the Home Office are almost always along the vague lines of the person in question not being “conducive to the public good”. Below are some the most high-profile cases.

Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer

(Image: Mark Tenally/Demotix)

The American “counter-jihadists” were last May invited to speak at an EDL rally in Woolwich, London, at the scene of the brutal murder of Drummer Lee Rigby. However, they both received letters from the Home Office, informing them that based on past statements they were barred from entering the UK. One of Geller’s comments highlighted was: “Al-Qaeda is a manifestation of devout Islam… It is Islam.” In a joint statement, they declared that “…the British government is behaving like a de facto Islamic state. The nation that gave the world the Magna Carta is dead”.

Geert Wilders

(Image: Frederik Enneman/Demotix)

In 2009, leader of the far-right Dutch Party for Freedom was set to travel to the UK to show his controversial film Fitna — which has been widely labelled as Islamophobic — in the House of Lords. Despite being told by the Home Office before travelling the he was barred from entry because his views “threaten community harmony and therefore public safety”, he still flew to Heathrow, where he was eventually stopped at the border. “Even if you don’t like me and don’t like the things I say then you should let me in for freedom of speech. If you don’t, you are looking like cowards,” was his message to British authorities at the time. The decision was later overturned.

Fred Phelps and Shirley Phelps-Roper

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The father and daughter, both members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church — know, among other things, for picketing funerals — were planning on coming to Leicester to protest against a play about a man killed for being gay. The UK Border Agency said at the time: “Both these individuals have engaged in unacceptable behaviour by inciting hatred against a number of communities.”

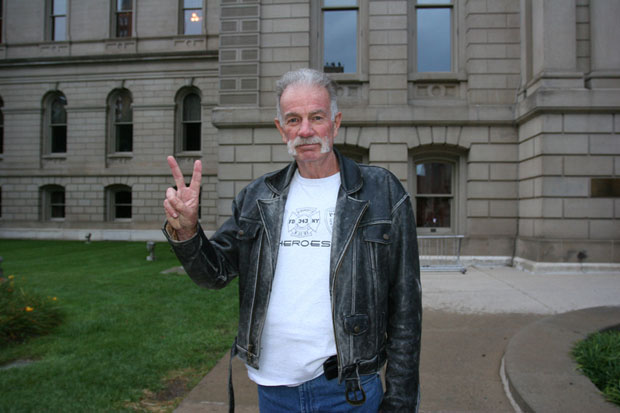

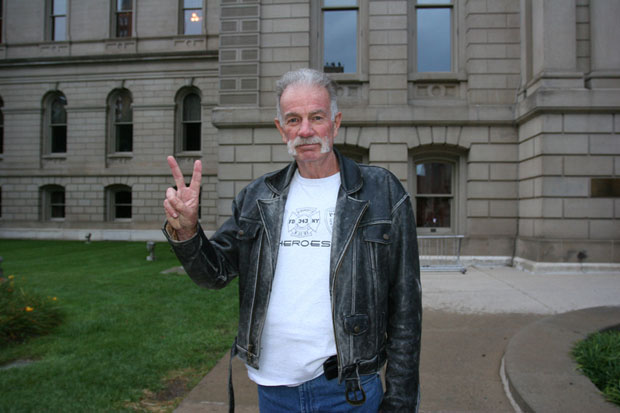

Terry Jones

(Image: Mark Brunner/Demotix)

The American pastor became known across the world when he threatened to stage a mass burning of the Koran in 2010 to mark the anniversary of 9/11 — something which in the end did not take place. In 2011 he was invited to attend a number of demonstrations with far right group England Is Ours. However, he was banned by the Home Office, which cited “numerous comments made by Pastor Jones” and “evidence of his unacceptable behaviour”. Jones responded saying: “We feel this is against our human rights to travel and freedom of speech.”

Dyab Abou Jahjah

(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The then Belgium-based founder of the Arab European League spoke at a meeting of the Stop The War Coalition in March 2009. He left the country with the intention of coming back after a few days, only to discover that he was barred from entering Britain. His organisation had previously published “a series of antisemitic and Holocaust revisionist cartoons in response to the Danish Muhammad cartoons controversy.” Around the time of his visit, the president of the Board of Deputies, Henry Grunwald QC, wrote to then-Home Secretary Jacqui Smith “raising concerns about Jahjah”. In a post on his website, he said he believed his ban was “mainly to do with the lobbying of the Zionists”.

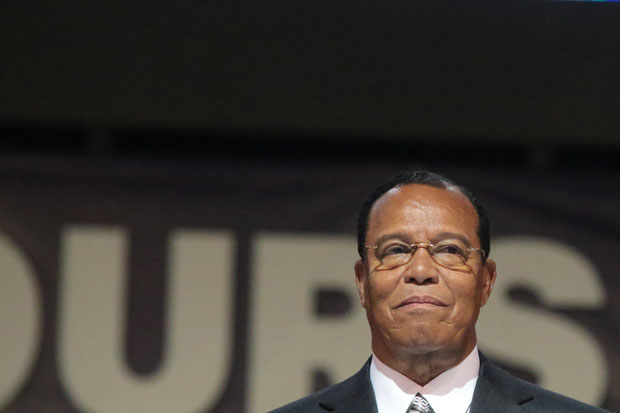

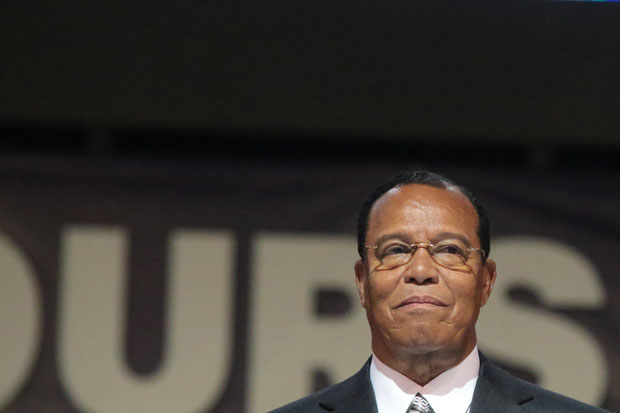

Louis Farrakhan

(Image: Thabo Jaiyesimi/Demotix)

The American Nation of Islam leader has been banned from entering the UK since 1986, due to racist and antisemitic remarks like calling Jews “bloodsuckers” and Judaism a “gutter religion”. The ban was briefly overturned in 2001 by a High Court ruling, but the government won out in the Appeals Court the following year.

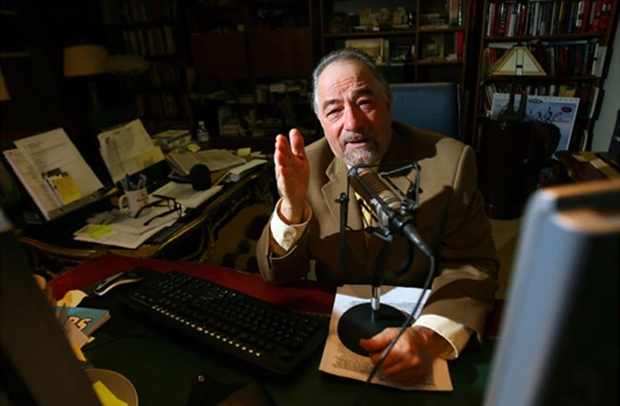

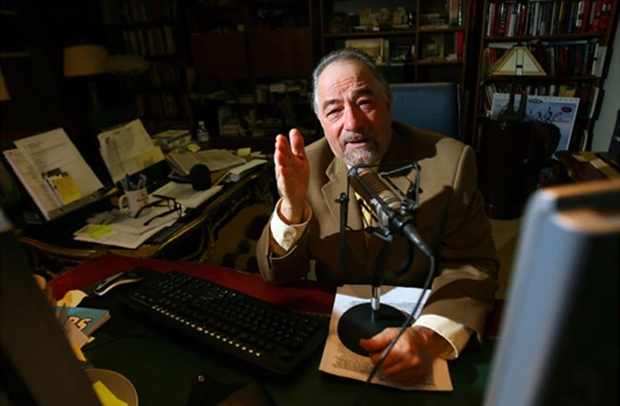

Michael Savage

(Image: Clifford Dombrowski/YouTube)

In 2009, then Home Secretary Jacqui Smith announced a 16-person banned-list, made public in a bid to explain the authorities reasoning for barring people from entering the country. On the list was shock-jock Savage — a popular American talk radio host, who has outraged listeners with comments like “Latinos ‘breed like rabbits'” and “Muslims ‘need deporting'”. He was banned for being “likely to cause inter-community tension or even violence”. Savage reacted with disbelief, claiming he would sue Smith. The ban was reaffirmed in 2011.

This article was originally posted on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Mar 2012 | Uncategorized

Cross posted from http://kenanmalik.wordpress.com/

Actually, I seem to have been talking about this for much of the past two decades; ‘this’ being free speech, multiculturalism, Islam, Islamism, the issues at the heart of DV8’s extraordinary new show Can We Talk About This? now playing at London’s National Theatre. Lloyd Newsom’s company has, for more than quarter of a century, blurred the lines between dance and theatre as a way of, in the company’s own words, ‘reinvesting dance with meaning, particularly where this has been lost through formalised techniques’. It has always tackled controversial and difficult subjects, but the latest is likely to be the most challenging yet.

I was one of a host of people whom Lloyd Newsom interviewed in preparation for the show. I finally got to see the finished product on Friday. It was a strange experience having my words spoken back to me from the stage. The whole show is stitched together through other people’s voices, voices taken from those various interviews, and from interviews and debates on TV and on stage, including a spat between Shirley Williams and Christopher Hitchens on BBC’s Question Time and Jeremy Paxman mediating between Anjem Choudhury and Maajid Nawaz onNewsnight. You experience it in the audience as a tapestry of ideas, always moving and whirling like a dancer’s ribbon, but which builds up thread by thread, layer by layer, into a tightly woven, almost inescapable, argument. The voices are not recordings; every word comes out of the mouths of the dancers, which adds to the sense of perpetual motion. Their ability to dance and talk at the same time still leaves me breathless and bewildered.

The show opens, as most of those in the audience must have known, with a cast member demanding of the spectators ‘Do you feel morally superior to the Taliban?’ It’s a nod to Martin Amis who asked that same question to a hostile audience in a notorious debate at London’s ICA, back in 2007. It is hardly the most sophisticated of questions. Yet its very unsophistication reveals so starkly the spectre haunting the liberal moral swamp. Had the audience been asked ‘Do you feel morally superior to the BNP?’, or even ‘Do you feel morally superior to David Cameron?’, I have no doubt that a forest of hands would have been raised. As it happened only a handful were willing to admit that their values might have been a mite more elevated that those of the Taliban. This has nothing to do with English reticence – the show has already played in Australia and in Europe, and the question elicits the same response (or non-response) everywhere. Everywhere it creates the same moral discomfort. As one Australian critic put it, after the opening night last year in Sydney, ‘It’s as if a quiet little bomb had been thrown into the audience to disturb its equilibrium from the start’.

It is that sense of moral reticence – even of guilt – at the thought of passing judgment upon other cultures, revealed by the reluctance to think that one could be morally superior to the Taliban, that lies at the heart of Can We Talk about This? The show begins with the infamous Ray Honeyford row in Bradford in 1985, and moves through the Rushdie affair, the murder in 2004 of Dutch film maker Theo van Gogh, the Danish cartoons controversy the following year, and the banning in 2009 of Dutch MP Geert Wilders from this country because of his anti-Islamic film Fitna, all interwoven with discussions of forced marriage, honour killings, jihadism. The emotion that courses through every scene is a pulsating anger at the way that liberal cowardice has interwoven with multicultural naivety to allow Islamist extremist to silence critics and to betray both principles and people.

The choreography is sublime, the movement spellbinding. Dancers contort themselves and crawl and slide and slither in a mesmerizing metaphor for liberal agonies. Yet while the interaction of the dancers with each other, and with the physical space, is exhilarating, the interplay of movement and word is less so. There are times when the two fuse seamlessly. The scene in which two women, including Javinder Sanghera of the Asian women’s centre Karma Nirvana, explain ‘honour’ violence while fluidly making and remaking themselves is quite stunning. In other scenes, however, too great a gap opens up between what is being said and what is being done. There was quite a bit of tittering during the show, because many in the audience seemed to read the dancing more as a reworking of John Cleese’s Ministry of Silly Walks than as an accompaniment to a political polemic.

And it is as a polemic that the show is at its weakest. I have been a critic of multiculturalism from long before it was fashionable to be one, and I am a fundamentalist in defence of free speech. And yet Can We Talk about This? left me feeling somewhat queasy. Why? Because, as Sunder Katwala observes, there is a naivety gnawing away at the heart of the show, a naivety that emerges out of the broader debate about multiculturalism

Discussions about multiculturalism often conflate two issues: the idea of diversity as lived experience and that of multiculturalism as a set of policies through which to manage such diversity. The experience of living in a society transformed by mass immigration, a society that is less insular, more vibrant and more cosmopolitan, is positive. As a political process, however, multiculturalism has come to mean something very different. It has come to describe a set of policies, the aim of which is to manage diversity by putting people into ethnic boxes, defining individual needs and rights by virtue of the boxes into which people are put, and using those boxes to shape public policy. It is a case, not for open borders and minds, but for the policing of borders, whether physical, cultural or imaginative.

This conflation of lived experience and political policy has proved highly invidious. On the one hand, it has allowed many on the right – and not just on the right – to blame mass immigration for the failures of social policy and to turn minorities into the problem. On the other hand, it has forced many traditional liberals and radicals to abandon classical notions of liberty, such as an attachment to free speech, in the name of defending diversity.

DV8 is clearly presenting a critique of multiculturalism in the second sense, that is as a set of political policies aimed at institutionalising cultural differences, while defending the idea of a diverse society. This is the progressive critique of multiculturalism, a case for open borders and open minds. Yet, many of those whose voices the show uses to make its argument have a very different starting point. Their critique is not of multicultural policies, but of immigration, Islam and diversity. In the opening scene, the Bradford headmaster Ray Honeyford is presented as a nice, moderate, if conservative, figure, only looking out for the children in his care. To describe Honeyford as ‘conservative’ is a bit like describing Enoch Powell as ‘conservative’. It is not untrue, but it misses so much about their views. Honeyford, in fact, held Powellite views on race, immigration and diversity. In 1984, while headmaster of Bradford’s Drummond Middle School, he wrote an essay on ‘Education and Race: An Alternative View’ in The Salisbury Review (which, too, was not a ‘conservative’ but a reactionary magazine), to which his critics took umbrage and which eventually led to his forced resignation. The essay certainly pointed up the disastrous consequences of many educational practices introduced in the name of diversity. But Honeyford’s critique was as much of what he called ‘multi-racialism’ as of what is now called multiculturalism. He was hostile to immigration, contemptuous of non-British cultures and possessed of a little-Englander view. His comments on Caribbean culture give a flavour of his attitudes:

“‘Cultural enrichment’ is the approved term for the West Indian’s right to create an ear-splitting cacophony for most of the night to the detriment of his neighbour’s sanity, or for the Notting Hill Festival whose success or failure is judged by the level of street crime which accompanies it.”

Elsewhere in the essay Honeyford talks of the ‘hysterical political temperament of the Indian subcontinent’, lambasts a ‘half-educated and volatile Sikh [who] usurped the privileges of the chair’ at a meeting, describes Pakistan as ‘a country which cannot cope with democracy’, and pins the blame for the educational failure of minority children on ‘An influential group of black intellectuals of aggressive disposition, who know little of the British traditions of understatement, civilised discourse and respect for reason’.

Honeyford’s critics were wrong to try to silence him. But in calling them to account it is important not to present Honeyford himself as a hero or a moderate or to whitewash his views and his record.

Similarly with Geert Wilders. Can We Talk About This? presents the Dutch politician as a doughty defender of free speech, banned from this country by a Home Office too cowardly to stand up to Muslim activists outraged by his film Fitna. The second part is true. The first part is not. Wilders is a reactionary populist who poses a bigger threat to liberties than most of his critics. He has campaigned in Holland to ban the Qur’an as ‘hate speech’, called for a ‘spring-cleaning of streets’ to sweep away Muslims, proposed a ‘Head Rag Tax’ on Muslim women wearing the hijab, and threatened the mass deportation of Muslims. The fact that Wilders is an odious reactionary does not mean that he should be banned from this country or that his film (which is also odious and reactionary) should be censored. But neither does the fact that he and his film were (temporarily) banned mean that we should treat him as a free speech hero.

Criticism of reactionaries, such as Honeyford or Wilders, and of illiberal actions against Islamists, such as the six-year prison sentences handed down to London protestors against the Danish cartoons, is conveyed in Can We Talk About This? largely through the voices of Islamist extremists. There are virtually no secular voices, radical or liberal, or Muslim mainstream ones, confronting the likes of Honeyford or Wilders, or challenging the suppression of Islamic dissent. This inevitably serves to marginalise such criticism, to make it appear as irrational and as unacceptable as Islamism itself, and to give legitimacy to the reactionary assaults of multiculturalism and to the illiberal actions of the state. This, in turn, warps the critique of multiculturalism, and allows the reactionary voices to hijack it. There can be no progressive challenge to multiculturalism, nor defence of free speech, without also a challenge to the rightwing, populist, often racist, critiques that now increasingly populate the landscape, and a willingness to defend the right of all people to express their beliefs, however odious those beliefs may seem.

Perhaps such criticism is unfair. After all, Can We Talk About This? is physical theatre not a roundtable discussion. Yet the show needs, indeed demands, such criticism, ironically, because of the depth of research that has gone into the production and the very intelligence of the argument, because it sets itself up, from that very first question to the audience, as an engaged polemic, as a challenge to the accepted narrative on free speech, multiculturalism and Islam. The ambition of the show, and its willingness to stomp all over the debate, is its great strength; its unwillingness to be more nuanced about whose boots are stomping where is its great weakness.

Can We Talk About This? is, like all DV8 works, both thought provoking and gut-wrenching, food for mind and heart. It is the kind of bold, polemical spectacle that the theatre so badly needs, a world away from the insipid offerings that all too often litter the West End stage. Yet both as a critique of multiculturalism and as a defence of free speech it is to be found wanting. Go see it – it is, as I said, unmissable theatre. And then do talk about this.