6 Jan 2023 | FEATURED: Mark Frary, Iran, News and features

Ramita Navai in Iran in 2005, at a time when women journalists were temporarily allowed in to report on football matches

Up to 20,000 people have now been detained as a result of the protests that have wracked Iran in the past three months. Those who have been detained have been subject to physical and psychological torture, rape and been made to make forced confessions. Some, including 22-year-old Mahsa (Jina) Amini whose death sparked the current protests, have died in custody.

The British-Iranian investigative journalist and documentary maker Ramita Navai knows only too well what those who have been detained are facing. She has been detained by the Iranian authorities several times over the years.

Her first arrest came just after she had started working as Tehran correspondent for The Times and was covering the anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

“I was at a rally with a lot of other journalists and I was interviewing some Iranians. Before I knew it, two undercover intelligence agents had taken me away; none of my colleagues saw me being taken. It was a terrifying experience. They took me to an abandoned warehouse with broken windows and flexes hanging from the ceiling and there was an armed man standing outside the room. They took all my possessions and carried a table and chairs into the room before starting with a good cop/bad cop routine. It was very manipulative psychologically and was designed to break me. They started telling me that I had been asking anti-revolutionary questions and said I had been telling people how to answer. It was all lies but I was utterly unprepared for this.”

Her interrogators asked her whether she had heard of Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian photojournalist who had been killed in police custody shortly before Navai had arrived in Iran.

“Every journalist knew what had happened to her and they were hinting that I would suffer the same fate. I was so petrified I started sobbing.”

Navai was one of the lucky ones. A few hours after being taken, one of her journalist colleagues, Jim Muir of the BBC, noticed she was missing and started talking to the Iraniansat the rally. One whispered to him that they had seen her being taken away.

“He phoned up the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance and said we know you have got her, you had better release her otherwise I am going to cause a fuss about this.”

Navai was released shortly afterwards.

Since then Navai has won numerous awards for her documentary work, including an Emmy for her PBS Frontline documentary Syria Undercover in 2012 and a Royal Television Society Journalism Award for her documentary on tracking down refugee kidnap gangs for Channel 4.

But it is Iran, the country of her birth, where her heart lies.

Her 2014 book City of Lies, which won her the Royal Society of Literature’s Jerwood Award for non-fiction, tells the stories of ordinary Iranians forced to live extraordinary lives: the porn star, the ageing socialite, the assassin and enemy of the state who ends up working for the Republic, the dutiful housewife who files for divorce, and the old-time thug running a gambling den.

Tehran, the City of Lies of the title, is described with romantic nostalgia but rails against the hypocrisy of the regime.

Navai feels there is “no turning back” from the current protests.

“This time feels very different. I think the protests are unlike anything we have ever seen. Significantly, they span all social classes, ethnicities and the protests have happened in every one of Iran’s provinces. The protests have been a unifying force, uniting Iranians of all colours against the regime. I don’t think the regime will fall imminently although I do think something has shifted and there is no going back from that. I think a very different future for Iran has now become a reality in a way that it wasn’t a year ago.”

She adds, “The most organised groups seem to be the Iranian feminist and women’s rights networks because they have been used to mobilising for such a long time. They are used to being arrested and imprisoned. They issue secret missives and are coordinating with some of the activists in prison.”

Navai and her mother Laya at a demonstration in London in support of the Iranian protests

Navai believes it is the moment for Iranian women and those of Generation Z in particular.

“The women’s groups were crushed in 2009 – they were a thorn in the side of the regime. What we are seeing now is a strengthening and a rising up,” she says. “In 2009, it was people my age who were and are very fearful of the regime. The younger generation – Generation Z – are absolutely fearless. My generation always felt like they had something to lose. The regime is brilliant at playing this game of giving people just enough freedom to shut them up. This younger generation have grown up in a very different world, a completely connected Iran in which they have been influenced by global popular culture. They know what is out there in the world. They know all the opportunities that should be open and available to them and they are angry and they are fearless.”

She believes a sexual awakening is also happening in Iran.

“We are talking about this being a women-led uprising, partly this is because this sexual awakening has changed the socio-cultural dynamics for Generation Z. In real terms, virginity is not the thing it used to be. So many couples are living together outside marriage that the Supreme Leader’s office issued an edict saying how immoral it is. These are ordinary Iranians, not just the middle and upper class. There has been this massive socio-cultural shift. Generation Z are used to different social norms and strictures and they are not going to be told what to do. They want full autonomy not only over their bodies but over their lives.”

In the intervening years, Iranian people have become even more resourceful than in previous protests.

“This is what 43 years of a repressive and censorious regime have done,” says Navai. “Most Iranians have VPNs [virtual private networks]. There are occasional blackouts – not all VPNs keep working so they have to change them. Iranian exiles are paying for that service, sending login details to Iranians within the country to help them mobilise. They have also been mobilising in quite interesting ways using social media but actually also old-fashioned meet-ups.”

The recent public expressions of protest by leading Iranians, such as the actress Taraneh Alidoosti and a women’s basketball team, are “hugely significant”, she believes.

“They are emboldening the protesters to rise up against the regime,” she says. “I also think these high-profile protests and the world’s media and social media are a really important tool for this uprising. It is the oxygen that is keeping these protests going. Without the world watching I think the regime would be far more brutal. It has already been very brutal. It hasn’t unleashed its might yet and I am scared that it will.”

In many revolutions, it is when the military switches sides, abandoning their loyalty to the leaders under pressure from the people that real change happens. Indeed, some experts have speculated that change will only come to Iran when that happens. However, there are good reasons to think that may not happen.

Iran’s regular armed forces number around 420,000 plus another 300,000 or so who are reservists who can be called up.

What is perhaps stopping them from switching their loyalty is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, set up by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979.

“You have 100,000 to 150,000 soldiers who are the Revolutionary Guard,” says Navai. “It was set up to ensure loyalty to the Supreme Leader and the state and act as a counter-balance to monitor the ordinary forces. These Revolutionary Guardsmen are better trained, far better equipped and are far more loyal – they are ideologically motivated and answer directly to the Supreme Leader. It will be a big turning point if the army turns, however I think that could also result in a bloodbath.”

There are also the Iranian regime’s allies beyond the country’s borders – the Shia militia in Iraq and Hezbollah.

What is clear from Navai’s City of Lies is the widespread hypocrisy of the Iranian regime. It tells stories of clerics using prostitutes and the ubiquity of porn.

“This is one of many reasons that Iranians have had enough,” says Navai. “The regime is not only corrupt politically, it is corrupt morally. While the state enforces laws that govern its citizens’ most intimate affairs meanwhile people in power do as they please. You have people in power whose children are partying in Iran and across the world, doing drugs, wearing whatever they want and having normal sexual relations that are not allowed under the regime. It is this hypocrisy that people are finally fed up with.”

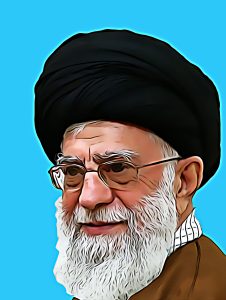

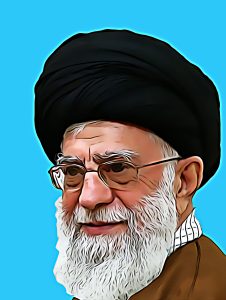

1 Dec 2022 | Iran, Tyrant of the Year 2022

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

“This is a classic from the authoritarian playbook,” says Index’s associate editor Mark Frary. “How often do you see such pro-government rallies in truly free countries? You have to wonder what pressure they bring to bear on the people present to agree to take part in events which are clearly designed to drown out true protests.”

The September rallies were a largely unsuccessful attempt, at least outside Iran, to distract attention from widespread protests in the country following the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, detained by Iran’s notorious Gasht-e Ershad.

“These so-called ‘morality police’ uphold respect for Islamic morals, including detaining women who they see as being improperly dressed, such as wearing revealing or tight-fitting clothing or not wearing the required hijab,” says Frary.

Since then the country has been wracked by protests, which have been violently subdued. Oslo-based NGO Iran Human Rights say that a minimum of 448 people, including 60 children, have been killed in the protests. Many of those paying the ultimate price for protest have been women.

The Iranian authorities have been trying to keep a lid on the news by shutting down the internet in the country. Iran’s parliament has also been working on a draft bill that seeks to impose further restrictions on internet access for people in Iran, including criminalising the use of virtual private networks.

11 Oct 2022 | Iran, News and features

The death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in Iran following her arrest by the “morality police” has sparked widespread protests across the country, with women taking a prominent role in demonstrating against their unequal treatment in the country. The Iranian regime, led by Ayatollah Khamenei, has responded with deadly violence.

Since Amini’s death on 16 September, precipitated by her arrest for not wearing the hijab correctly, at least 185 people, including at least 19 children, have been killed in the nationwide protests across Iran, according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI). The deaths of several young women involved in the protests has led to a growing chorus of outrage, both within the country and internationally.

Among the dead is Sarina Esmailzadeh, a 16-year-old girl who was killed following protests on 22 September in Mehrshahr, just outside Tehran, reportedly due to repeated baton blows by security forces. Authorities have aired “so-called” confessions by alleged family members stating that her death was suicide, which have been called into question.

Nika Shakarami (right) has also died, allegedly at the hands of the Iranian security forces, after she was pictured burning her hijab. The 17-year-old disappeared for nine days before her badly beaten body was identified by her family in a morgue.

Nika Shakarami (right) has also died, allegedly at the hands of the Iranian security forces, after she was pictured burning her hijab. The 17-year-old disappeared for nine days before her badly beaten body was identified by her family in a morgue.

Women human rights defenders and journalists are being targeted. Femena reports that women’s rights activist Narges Hosseini, one of the “Girls of Revolution Street”, who protested back in 2017 and 2018 about the compulsory hijab, was arrested on 22 September in Kashan in central Iran. Four years ago, she spent three months in prison on charges of “encouraging prostitution” and “non-observance of hijab”.

CHRI has also reported on the arrest of Niloufar Hamedi, a well-known journalist who first revealed the circumstances surrounding Mahsa Amini’s death that same say. Hamedi has been placed in solitary confinement in the notorious Evin prison.

Others who have been detained include journalist and woman human rights defender, Elaheh Mohammadi, Kurdish writer and filmmaker Mozhgan Kavusi and photojournalist Yalda Moayeri, according to Femena.

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraeei, an Index contributor who was only released from prison in May 2022 after being imprisoned in 2014 on charges of insulting the Supreme Leader and spreading propaganda against the state, has also been rearrested.

The attacks and arrests have so far not managed to silence women, who continue to protest. According to the BBC World Service’s Rana Rahimpour women are walking the streets of Tehran with no hijab and cars are honking their support. School girls have also joined the protests. Social media posts that have gone viral show them going without a hijab and making rude gestures to and removing and covering the images of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei in their classrooms.

On 9 October, teenage girls in the city of Arak, southwest of capital Tehran, marched in protest chanting “death to the dictator”, before they were fired on with rubber bullets and tear gas by riot police.

Protests have also sprung up at universities across the country. Shots were fired indiscriminately by security forces at a protest at Tehran’s Sharif University on 8 October, according to CHRI. Students at the city’s University of Art held a demonstration on 10 October where they congregated to spell out the word “blood”. The same day, female students at the Polytechnic University chanted, “Tell my mother she no longer has a daughter” – a shocking reference to the fate that could befall the students for daring to protest.

Students of Amir Kabir university protest against the hijab. Photo: Darafsh Kaviyani

There are signs that support for the protests is spreading more widely. Oil workers in Iran, including port workers in Asaluyeh and refinery workers in Abadan, are striking in support of the protests. This could be significant as such protests have not been seen since the 1979 revolution.

The city of Sanandaj in Kurdistan has become the frontline of the protests and the regime has cracked down brutally, leading some to call the city a “war zone”. The CHRI reports that at least four people have been killed and more than 100 injured on 9 October. The government has deployed forces from outside the region in the city.

News that has emerged from Iran has made it out despite widespread internet and mobile network shutdowns in the country. NetBlocks has reported that the internet national mobile disruptions were in place once again and the internet had been cut in Sanandaj. Speaking to an Index correspondent over the phone from his home city of Sari in the north of Iran, the censored musician Mehdi Rajabian said: “It has become very difficult for me to access the free internet and the speeds of the platforms are very slow and blocked. I have to connect with a filter breaker and many times the filter breakers don’t work. Our communication is very slow.”

Such restrictions mean that the number of those killed, injured or detained is likely to be much higher.

There are signs that Iranians are increasingly looking to virtual private networks (VPNs) to help them circumvent the country’s internet broad censorship. Research by the VPN tracker Top10VPN.com shows that downloads of VPNs in Iran were 30 times higher at the end of September than in the previous 28 days and that demand for the services remains significantly heightened.

CHRI’s executive director Hadi Ghaemi feels that the situation is likely to worsen as Khamenei’s rule comes under growing pressure.

“The ruthless killings of civilians by security forces in Kurdistan Province, on the heels of the massacre in Baluchestan Province, are likely preludes to severe state violence to come,” said Ghaemi in a statement about the protests.

He said, “World leaders must move beyond statements of condemnation to collective action through an international front signalling to the government in Iran that the international community will not look the other way and conduct business as usual while it slaughters unarmed civilians.”

In response, Khamenei has said foreign states are responsible for driving the women’s protests. With support growing fast, he may soon no longer be able to lay the blame outside Iran’s borders.

22 Sep 2022 | Iran, News and features

Iranians are again finding it impossible to access the internet and social media messaging platforms after yet another shutdown by the country’s authorities. The move comes after protests erupted in the country, sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (right) last Friday.

Iranians are again finding it impossible to access the internet and social media messaging platforms after yet another shutdown by the country’s authorities. The move comes after protests erupted in the country, sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (right) last Friday.

Critics say the shutdown of services and the filtering of content is restricting freedom of expression and preventing peaceful protest. Access to news in Iran is strictly controlled by the government and for many Iranians, their only access to independent news sources is through digital platforms.

Amini, a Kurdish woman from Saggez in Iranian Kurdistan, was visiting relatives in Tehran on 13 September when she was arrested by the Gasht-e Ershad. These so-called “morality police” uphold respect for Islamic morals, including detaining women who they see as being improperly dressed, such as wearing revealing or tight-fitting clothing or not wearing the required hijab.

The morality police detained Amini as she and her brother were coming out of the city’s Haqqani metro station. Eyewitnesses said Amini was brutally assaulted by the agents inside their vehicle and then taken to a police station.

Two hours after her arrest, Amini went into a coma. She was then taken to Kasra Hospital where doctors said she had suffered a heart stroke and brain haemorrhage due to a fractured skull. She died on Friday, 16 September.

Ever since her death, protests have spread across the country, reaching more than 80 cities nationwide. In typical fashion, the authorities have responded by shutting down access to the internet in a bid to quell the protests.

Iran is one of the world’s biggest censors of the internet. The country has been concerned about the internet since the turn of the millennium and has been operating a sophisticated system of hardware and software-based content filtering ever since. A broad project now known as the National Information Network (NIN), and similar to China’s Great Firewall, was launched in 2005. It requires companies to use Iranian data centres and forces internet users to register using their social IDs and telephone numbers.

NIN was finally fully implemented in 2019 and that same year Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said of the internet, “During these past 40 years, and today as ever, the enemy’s propaganda and communication policy, as well as its most active programmes, have revolved around making people and even our officials and statesmen lose their hope in the future. False news, biased analysis, reversing facts, concealing the hopeful aspects, amplifying small problems and berating or denying great advantages, have been constantly on the agenda of thousands of audio-visual and internet-based media by the enemies of the Iranian people.”

The country also has a history of using internet shutdowns to crack down on dissent.

In 2019, protests broke out across the country when the Iranian government announced a 50 per cent increase in fuel prices and monthly rationing of petrol. More than 100 people died, according to reports. The government swiftly shut down the internet and mobile networks for several days.

In February 2021, at least ten fuel couriers in Sistan and Baluchistan province on the border with Pakistan were killed after a two-day stand-off triggered by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps blocking the road to the city of Saravan. The killings triggered demonstrations, leading to further deaths, and the regime shut down the internet across several cities in the province.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said at the time: “Blanket internet shutdowns violate the principles of necessity and proportionality applicable to restrictions of freedom of expression and constitute a violation of international human rights law.”

The protests around the death of Mahsa Amini have seen the Iranian authorities reach for the internet shutdown playbook once more.

NetBlocks and AccessNow report that internet access began to be disrupted in Tehran and other parts of the country on the day of Amini’s death and on Monday 19 September, internet access was shut down almost totally in parts of the Kurdistan province.

The KeepItOn coalition, of which AccessNow is a member, said that this represents Iran’s third internet shutdown in less than 12 months. They said the “repressive, knee-jerk response to recent protests seriously interferes with people’s right to freedom of expression and assembly”.

Iranians have increasingly resorted to using unfiltered channels to get their news, as the only parts of the internet that they can access are censored. By 2018, it was believed that more than half of Iran’s population were using Telegram. In April that year the judiciary banned the popular messaging app, claiming it has been used to organise attacks and street protests. Since then, Iranians have switched to WhatsApp and Instagram.

It comes as no surprise that with the current protests NetBlocks has reported that access to Instagram, one of the last remaining social media platforms in Iran, was restricted across all major internet providers on Wednesday 21 September.

The authorities appear to have clamped down because of the widespread nature of the protests and, perhaps more worryingly for the regime, a large number of video clips that have gone viral and which they are keen to suppress.

A peaceful protest in Saqqez

Not just the young

A clip of several men defending a woman who has removed her hijab

Another video clip shared on Twitter by British comedian Omid Djalili, whose parents are Iranian, suggested that, perhaps, attitudes may finally be changing in Iran.

Responding to the crackdown on protest and the internet shutdowns, experts from the UN Human Rights Council’s Special Procedures group said in a statement, “Disruptions to the internet are usually part of a larger effort to stifle the free expression and association of the Iranian population, and to curtail ongoing protests. State-mandated internet disruptions cannot be justified under any circumstances.”

“Over the past four decades, Iranian women have continued to peacefully protest against the compulsory hijab rules and the violations of their fundamental human rights,” the experts said. “Iran must repeal all legislation and policies that discriminate on the grounds of sex and gender, in line with international human rights standards.”

Speaking to Index, exiled Iranian film-maker Vahid Zarezdeh said the WhatsApp and Instagram ban means he has been cut off from his young son and the rest of his family still in the country.

He said, “In the absence of independent parties and free media, Iranian society gets its news and events, social and political issues from the internet. News reaches its audience very quickly and people can easily distinguish fake news from real news. How, you ask? The solution is very easy. By looking at the state television, you can understand which news is true and which is false. Whenever the government reacts sharply to news and prepares a report, it is very likely that the news is true, and when it ignores the news and is indifferent, it means that it is fake.”

State TV has been reporting on the protests but its coverage has focused less on the protests by women and instead suggesting that the unrest has been caused by Iran’s enemies, rather than spurred on by the regime’s crackdown. Certainly, TV viewers in the country have not seen the clips above.

“This is a system of repression and the Iranian regime does not care what the world community thinks about it and human rights,” said Zarezdeh.

He added, “It’s more than forty years since Iranian women started to be ignored by the Islamic regime. Now they have found the courage and belief to stand in front of the bullets with empty hands and without a scarf.

Nika Shakarami (right) has also died

Nika Shakarami (right) has also died

Iranians are again finding it impossible to access the internet and social media messaging platforms after yet another shutdown by the country’s authorities. The move comes after protests erupted in the country, sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (right) last Friday.

Iranians are again finding it impossible to access the internet and social media messaging platforms after yet another shutdown by the country’s authorities. The move comes after protests erupted in the country, sparked by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (right) last Friday.