25 Jul 2016 | Africa, Asia and Pacific, Burkina Faso, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen

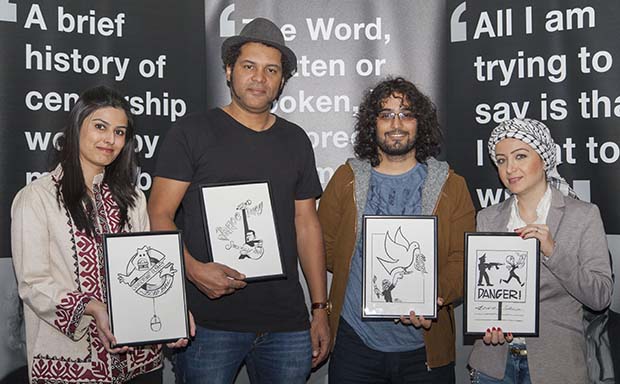

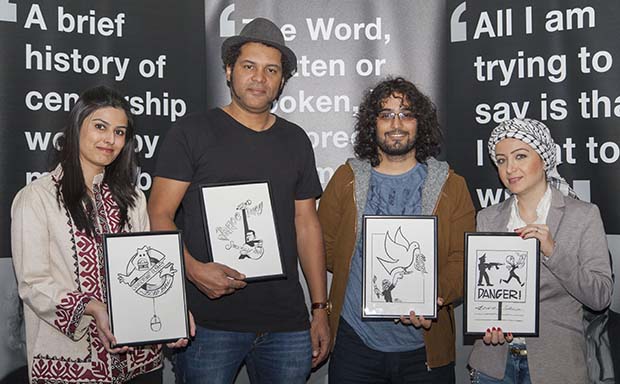

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

In the short three months since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2016 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

GreatFire / Digital activism

GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall, has just launched a groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country.

“Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” said co-founder Charlie Smith.

But why are VPNs needed in China in the first place? “The list is very long: the firewall harms innovation while scholars in China have criticised the government for their internet controls, saying it’s harming their scholarly work, which is absolutely true,” said Smith. “Foreign companies are also complaining that internet censorship is hurting their day-to-day business, which means less investment in China, which means less jobs for Chinese people.”

Even recent Chinese history is skewed by the firewall. The anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 last month went mostly unnoticed. “There was nothing to be seen about it on the internet in China,” Smith said. “This is a major event in Chinese history that’s basically been erased.”

Going forward, Smith is optimistic for growth within GreatFire, and has hopes the new VPN service will reach 100 million Chinese people. “However, we always feel that foreign businesses and governments could do more,” he said. “We don’t see this as a long game or diplomacy; we want change now and so I feel positive about what we are doing but we have less optimism when it comes to efforts outside of our organisation.”

Winning the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digital Activism has certainly helped morale. “With the way we operate in anonymity, sometimes we feel a little lonely, so it’s nice to know that there are people out there paying attention,” Smith said.

Murad Subay / Arts

During his time in London for the Index awards, Yemeni artist Murad Subay painted a mural in Hoxton, which was the first time he had worked outside of his home country. “It was a great opportunity to tell people what’s going on in Yemen, because the world isn’t paying attention,” he explained to Index.

Since going home, Subay has continued to work with Ruins, his campaign with other artists to paint the walls of Yemen. “We launched in 2011, and have continued to paint ever since.”

Last month, artists from Ruins, including Subay, painted a number of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse.

In his acceptance speech at the Index Awards, Subay dedicated his award to the “unknown” people of Yemen, “who struggle to survive”. There has been little change in the situation since in the subsequent months as Yemenis continue to suffer war, oppression, destruction, thirst and — with increasing food prices — hunger.

“The war will continue for a long time and I believe it may even be a decade for the turmoil in Yemen to subside,” Subay says. “Yemen has always been poor, but the situation has gotten significantly worse in the last few years.”

Subay considers himself to be one of the lucky ones as he has access to water and electricity. “But there are many millions of people without these things and they need humanitarian assistance,” he says. “They are sick of what is going on in Yemen, but I do have hope — you have to have hope here.”

The Index award has also helped Subay maintain this hope. As has the inclusion of his work in university courses around the world, from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, and King Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain.

Subay’s wife has this month travelled to America to study at Stanford University. He hopes to join her and study fine art. “Since 2001 I have not had any education, and this is not enough,” he explains. “I have ideas in my head that I can’t put into practice because i don’t have the knowledge but a course would help with this.”

Zaina Erhaim / Journalism

Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker Zaina Erhaim has been based in Turkey since leaving London after the Index Awards in April as travelling back to Syria isn’t currently possible. “We don’t have permission to cross back and forth from the Turkish authorities,” she told Index. “The border is completely closed.”

Erhaim is with her daughter in Turkey, while her husband Mahmoud remains in Aleppo.

“The situation in Aleppo is very bad,” she said. “A recent Channel 4 report by a friend of mine shows that the bombing has intensified, and the number of killings is in the tens per day, which hasn’t been the case for some weeks; it’s terrible.”

The main hospital in Aleppo was bombed twice in June. “Sadly this is becoming such a common thing that we don’t talk about it anymore,” Erhaim added.

She has largely given up on following coverage of the war in Syria through US or UK-based media outlets. “It is such a wasted effort and it’s so disappointing,” she explained. “I follow a couple of journalists based in the region who are actually trying to report human-side stories, but since I was in London for the awards, I haven’t followed the mainstream western media.”

Erhaim has put her own documentary making on hold for now while she launches a new project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting this month to teach activists filmmaking skills. “We are going to be helping five citizen journalists to do their own short films, which we will then help them publicise,” she said.

Documentary filmmaking is something she would like to return to in future, “but at the moment it is not feasible with the situation in Syria and the projects we are now working on”.

Bolo Bhi / Campaigning

The last time Index spoke to Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit, all-female NGO fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy, the country’s lower legislative chamber had just passed the cyber crimes bill.

The danger of the bill is that it would permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet. “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech,” Aziz told Index.

Thankfully, when the bill went to the Pakistani senate — which is the upper house — it was rejected as it stood. “Before this, we had approached senators to again get an affirmation as they’d given earlier saying that they were not going to pass it in its current form,” Aziz added.

Bolo Bhi’s advice to Pakistani politicians largely pointed back to analysis the group had published online, which went through various sections of the bill and highlighting what was problematic and what needed to be done.

This further encouraged those senators who were against the bill to get the word out to their parties to attend the session to ensure it didn’t pass. “It’s a good thing to see they’ve felt a sense of urgency, which we’ve desperately needed,” Aziz said.

“The strength of the campaign throughout has actually been that we’ve been able to band together, whether as civil society organisations, human rights organisations, industry organisations, but also those in the legislature,” Aziz added. “We’ve been together at different forums, we’ve been constantly engaging, sharing ideas and essentially that’s how we want policy making in general, not just on one bill, to take place.”

The campaign to defeat the bill goes on. A recent public petition (18 July) set up by Bolo Bhi to the senate’s Standing Committee on IT and Telecom requested the body to “hold more consultations until all sections of the bill have been thoroughly discussed and reviewed, and also hold a public hearing where technical and legal experts, as well as other concerned citizens, can present their point of view, so that the final version of the bill is one that is effective in curbing crime and also protects existing rights as guaranteed under the Constitution of Pakistan”.

A vote on an amended version of the bill is due to take place this week in the senate.

Smockey / Music in Exile Fellow

Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile Fellow at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, and last month his campaigning group Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) won an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award.

“This was was given to us for our efforts in the promotion of human rights and democracy in our country,” said Smockey. The award was also given to Y en a marre (Senegal) and Et Lucha (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

“We are trying to create a kind of synergy between all social-movements in Africa because we are living in the same continent and so anything that affects the others will affect us also,” Smockey added.

Le Balai Citoyen has recently been working on programmes for young people and women. “We will also meet the new mayor of the capital to understand all the problems of urbanism,” Smockey added.

While his activism has been getting international recognition, he remains focused on making music with upcoming concerts in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, and he is currently writing the music for an upcoming album. A major setback has seen Smockey’s acclaimed Studio Abazon destroyed by a fire early in the morning of 19 July. According to press reports the studio is a complete loss. The cause is under investigation.

Despite this, Smockey is still planning to organise a new music festival in Burkina Faso. “We want to create a festival of free expression in arts,” Smockey said. “And we are confident that it will change a lot of things here.”

He is thankful for the exposure the Index Awards have given him over the last number of months. “It was a great honour to receive this award, especially because it came from an English country,” he said. “My people are proud of this award.”

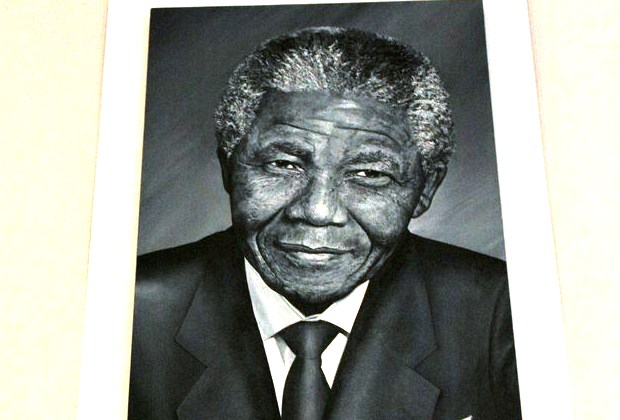

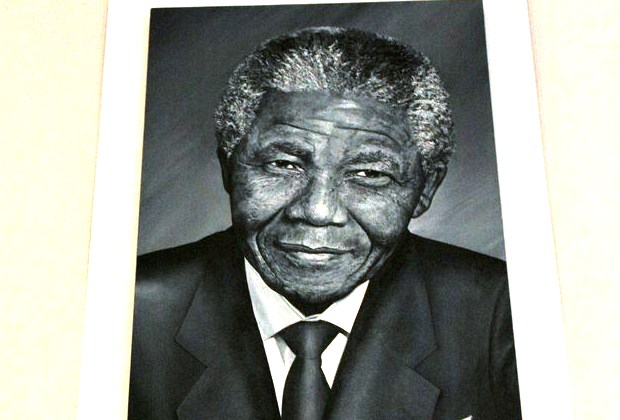

18 Jul 2016 | Africa, Magazine, mobile, South Africa

Index has released a special collection of apartheid-era articles from the Index on Censorship magazine archives to celebrate Nelson Mandela day 2016. Holly Raiborn has selected the collection, tracing the breadth of writing during the apartheid era from authors both in the country and in exile. The articles selected trace the history of this period in South Africa’s history. Significant South African writers, including Nadine Gordimer, Don Mattera, Pieter-Dirk Uys and Desmond Tutu, discuss the impacts this era of oppression had on themselves, their peers and their country. The collection will now form a reading list available to students who are researching the apartheid years, and will be available via Sage Publishing in university libraries.

Before 1948 “apartheid” was just a word in Afrikaans with a simple meaning: separateness. However, over the course of the next 50 years, the word “apartheid” would take on a new level of significance. The connotation of the word grew darker with every dissident banned, prisoner tortured, child left uneducated and home destroyed. Apartheid is no longer just a word; it carries the history of brutality, censorship and maltreatment of South Africans. For a limited period, Index and Sage are making the collection free to non-subscribers. For those who want to study the history of censorship further, Index on Censorship magazine’s archives are held at the Bishopsgate Institute in London and are free to visit.

Nadine Gordimer, Apartheid and “The Primary Homeland”

1972; vol. 1, 3-4: pp. 25-29

An address regarding the 1972 plans of the South African government to abolish the right of appeal against decisions brought by the State Publications Control Board, effectively ridding writers of a means to combat the rulings of government-appointed censors. The censorship in South Africa at this time caused a breakdown in communication between “the sections of a people carved up into categories of colour and language.”

Frene Ginwala, The press in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 3: pp. 27-43

An extensive report on the state of the “free” press in South Africa prepared for the United Nations’ Unit on Apartheid in November 1972. Ginwala posits that apartheid attempts to segregate freedom and this attempt “extinguishes freedom itself”.

Robert Royston, A tiny, unheard voice: The writer in South Africa

1973; vol. 2, 4: pp. 85-88

A personal narrative reflecting the experiences of Robert Royston as a black poet in South Africa during a period of popularity for black poetry amongst white readers. Royston describes a disconnect between the language he speaks and the language understood by the government and white citizens, although they technically share the same tongue.

Jack Slater, South African Boycott: Helping to enforce apartheid?

1975; vol. 4, 4: pp. 32-34

An article by a New York Sunday Times staff writer arguing that the proposed cultural boycott would ultimately negatively affect black South Africans more than white South Africans who were merely irritated. Slater feared black South Africans suffer from feelings of isolation from the outside world because of the cultural boycott.

Benjamin Pogrund, The South African press

1976; vol. 5, 3: pp. 10-16

A discussion regarding the often contradictory aspects of the South African “free” press in which newspapers censor themselves. Strict laws preventing communism, sabotage and terrorism were often twisted to prevent the publications of black viewpoints.

John Laurence, Censorship by skin colour

1977; vol. 6, 2: pp. 40-43

In the UK in the 1970s, news about South Africa was contributed by the white minority while black South Africans were not interviewed by major European news outlets about events predominantly affecting their community such as the Soweto riots. This article discusses the clear racial bias, blaming it for the misinformation and misconceptions in Europe about apartheid-era South Africa.

Brief reports: Bad days in Bedlam

1978; vol. 7, 1: pp. 52-54

A report regarding the glaring health violations within the overwhelmingly black South African mental hospitals that were largely ignored due to racial factors and censorship brought about with the 1959 Prisons Act. This act made reporting “false information” on prisons or prisoners punishable with jail time or fines which led to prison and mental patient camp, conditions being largely neglected in the media.

Robert Birley, End of the road for “Bandwagon”

1978; vol. 7, 2: pp. 6-8

An article about a significant yet short-lived South African journal, Bandwagon, whose purpose was to unite individuals banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. The act featured strictly enforced limits on social life and essentially made any meetings, social or otherwise, illegal for a banned person; therefore, the impact and importance of this publication should not be understated.

William A. Hachten, Black journalists under apartheid

1979; vol. 8, 3: pp. 43-48

Hachten discusses the new found power of being a black journalist (the literacy rate of black South Africans had recently surpassed whites) and the growing hazards of the profession in the late 1970s. Journalists were arrested for reporting the events of the Soweto riots and faced constant police and legislative pressure on top of fines and censorship imposed by the white-controlled newspapers they had no choice but to work for.

Don Mattera, Open Letter to South African whites

1980; vol. 9, 1: pp. 49-50

An address from a banned poet who pointed out the cruelty of white South African society so that they may never claim ignorance to the atrocities. He questions why his words are deemed so dangerous that he is not allowed to attend social gatherings like birthdays and funerals

Nadine Gordimer, The South African censor: No change

1981; vol. 10, 1: pp 4-9

Gordimer hypothesised that the successful appeal of her novel’s banning, and that of many novels by other white writers, was due to the fact that she is white. She argued that South Africa would never be rid of censorship until it was rid of apartheid.

Donald Woods, South Africa: Black editors out

1981; vol. 10, 3: pp. 32-34

Woods wrote about the shift from editors of South African newspapers facing fines for disobeying censorship statutes to jail time in the late 1970s and explained that this shift signalled that dissent and bold writing was permitted in white politics but would not be permitted from black perspectives. He argued that the reason the government did not censor the press entirely was because they enjoyed the façade of a “free press” and there was no reason for them to need full censorship.

Keyan Tomaselli, Siege mentality: A view of film censorship

1981; vol. 10, 4: pp. 35-37

Tomaseli explained that censorship was often as financially driven as it is culturally. He wrote that censorship interferes at three stages, namely during: finance, distribution and through state censorship law. Tomaseli expands on the circumstances that led to many different films being banned or harshly edited.

Mbulelo Vizikhungo Mzamane, No place for the African: South Africa’s education system, meant to bolster apartheid, may destroy it

1981; vol. 10, 5: pp. 7-9

Mzamane claimed that the Bantu Education Act of 1956 was clearly a ploy to create compliant Africans within a society increasingly controlled by Afrikaners. Bantu schools were essentially vocational training for servitude to whites and textbooks were blatant indoctrination, he argued.

Christopher Hope, Visible Jailers: A South African writer casts a humorous eye over the bannings by his country’s censors between 1979 and 1981

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 8-10

A clever take on the South African censor. Hope addresses the reasons and methodology of the South African censor with tongue and cheek commentary as he reviews the Publications Appeal Board: Digest of Decisions. This collection is comprised of the totality of decisions made by the South African Publications Appeal Board.

Sipho Sepamla, The price of being a writer

1982; vol. 11, 4: pp. 15-16

Sepamla writes about the struggles of continuing to write under such strict scrutiny by censors after the banning of his latest novel, A Ride on the Whirlwind. He speaks of the disenchantment experienced by any writer that has faced censorship and specifically black South African writers who faced this treatment all too often.

Barry Gilder, Finding new ways to bypass censors: How apartheid affects music in South Africa

1983; vol. 12, 1: pp. 18-22

Music was divided along race and class lines. Music was banned under the Publications Act if it was found to be unsafe to the state, harmful to the relationship between members of any sections of society, blasphemous, or obscene Songs with even symbolic mention of freedom or revolution were banned.

Barney Pityana, Black theology and the struggle for liberation

1983; vol. 12, 5: pp. 29-31

Reverend Pityana wrote of the paradox that Christianity teaches that all are equal under god but the church in South Africa still degraded and segregated. He writes that The Bible teaches that all are created in God’s image and the plight of the Jews and other marginalised groups within the Bible give hope, guidance and reassurance to those suffering under apartheid.

Miriam Tlali, Remove the chains: South African censorship and the black writer

1984; vol. 13, 6: pp. 22-26

Tlali, a black female South African novelist, addresses the added difficulties of being black and a woman in Afrikaner-controlled society. She speaks both from personal experience and about the struggles of her peers.

Johannes Rantete, The third day of September

1985; vol. 14, 3: pp. 37-42

An honest first-hand account of the Soweto riots by a 20-year-old unemployed black South African. Rantete wrote a sympathetic eyewitness report of the September riot and the first reaction of the South African authorities to confiscate and ban it.

Alan Paton, The intimidators

1986; vol. 15, 1: pp. 6-7

The white South African novelist on the intimidation tactics and stalking committed by the security police after his controversial novel, Cry, The Beloved Country, was published. He notes that he suspects his treatment would have been even worse had he been black.

Anthony Hazlitt Heard, How I was fired

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 9-12

Former editor of the Cape Times, who was awarded the International Federation of Newspaper Publishers’ Golden Pen of Freedom in 1986, Heard was dismissed from his position after his interview with banned leader of the African National Congress Oliver Tambo. Heard speaks about 16 years of editing under apartheid and the circumstances surrounding his dismissal in August 1987.

Anton Harber, Even bigger scissors

1987; vol. 16, 10: pp. 13-14

‘The importance of international pressure in giving a measure of protection to the South African press cannot be overestimated’ wrote the co-editor of the Johannesburg Weekly Mail in this assessment of Botha’s policy towards the alternative press. Harber offered a compelling plea for protection of the South African alternative press by the international media.

Jo-Anne Collinge, Herbert Mabuza, Glenn Moss and David Niddrie, What the papers don’t say

1988; vol. 17, 3: pp. 27-36

An extensive review of restrictions in South Africa at that time including the Defence Act, Police Act, Prisons Act, Internal Security Act and the Publications Act. The writers offer suggestions for the safety and protection of journalists in the future.

Richard Rive, How the racial situation affects my work

1988; vol. 17, 5: pp 97-98, 103

Rive discusses the racial factors that have contributed to his writing style and the works of any black writer in South Africa. He emphasises the hypocrisy of the society he lives in which will criticise black writers as simplistic but not allow quality education and where the books of black writers sitting in libraries that they are not allowed to enter.

Albie Sachs, The gentle revenge at the end of apartheid

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 3-8

Albie Sachs was asked by Index on Censorship to look ahead to constitutional reform that was not foreseeable at that point and how to enshrine freedom of expression in a post-apartheid South Africa. Four months later came the unbanning of the ANC on 2 February, the release of Nelson Mandela on 11 February and his reunion with Oliver Tambo in Sweden on 12 March, all of which promised real change. These are extracts from the conversation about a future South Africa. He offers suggestions for the then-looming transition from apartheid to democracy.

Oliver Tambo, We will be in Pretoria soon

1990; vol. 19, 4: pp. 7

In May 1986 Oliver Tambo, president of the African National Congress, was interviewed by Andrew Graham. The ANC president discussed the beginning of the end for apartheid and traces the lineage of the racism that fuelled the apartheid for nearly 50 years. Tambo optimistically plans for a new reign of government made up of representation that actually reflects the populous.

Nadine Gordimer, Censorship and its aftermath

1990; vol. 19, 7: pp. 14-16

On 11 July 1979, Nadine Gordimer’s novel Burger’s Daughter was banned by the South African directorate of publications on the grounds – among others – that the book was a threat to state security. After an international outcry the director of publications appealed against the decision of his own censorship committee to the publications’ appeal board. In this article, Nadine Gordimer reflects on these events, and on the new censorship policy they heralded. Gordimer reflects on censorship under previous administrations and what she expects from President FW de Klerk’s reign as president.

Nadine Gordimer, Act two: one year later

1995; vol. 24, 3: pp. 114-117

A reflection on how far South Africa had come and still had to go by this frequently banned author. Using the Descartes method, Gordimer considers the role reversal that has occurred in post-apartheid South Africa as her once banned colleagues ascend to political power.

Desmond Tutu, Healing a nation

1996; vol. 25, 5: pp. 38-43

An Index interview with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Tutu discusses the urgency of healing the past before South Africa can truly move on to a brighter future. This brighter future was to be achieved with the aid of the Truth Commission. He argued that only honesty, compassion and forgiveness would lead to national unity in South Africa, even if that means prosecuting former ANC members. He stresses that the commission’s goal is reparations and not compensation.

Pieter-Dirk Uys, The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but…

1996; v0l. 25, 5: pp. 46-47

Famed satirist Pieter-Dirk Uys questioned if information about the atrocities of the apartheid could actually be uncovered by the Truth Commission. Uys asked how the country could heal when so many willing participants in the apartheid already seemed eager to forget or to forge their own accounts of history to avoid blame. His pessimistic view contrasted with that of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s.

All articles from Index on Censorship magazine, from 1972 to 2016, are available via Sage in most university libraries. More information about subscribing to the magazine in print or digitally here.

8 Jul 2016 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Russia, Turkey, United Kingdom

Click on the dots for more information on the incidents.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Turkey: DIHA reporter arrested in Batman

4 July 2016: Dicle News Agency reporter Serife Oruc was sent to court on the charges of being “member of an illegal organisation”, news website Bianet reported. Oruc was arrested with two other men who were in the same car with Oruc, Emrullah Oruc and Muzaffar Tunc.

All three were transferred to a prison in Batman.

UK: Journalist claims Telegraph censored article critical of Theresa May

2 July 2016: The Daily Telegraph pulled a comment piece critical of Theresa May as May fought to become the leader of the Conservatives.

The piece was published on 1 July in the news section of the Telegraph but was subsequently taken down from the website. It was entitled “Theresa May is a great self-promoter but a terrible Home Secretary”.

“Daily Telegraph pulled my comment piece on Theresa May ministerial record after contact from her people #censorship”, journalist Jonathan Foreman tweeted on 2 July.

The journalist authorised Media Guido to republish the piece and it can be read on their website.

Russia: Free Word NGO declared a “foreign agent”

1 July 2016: The Pskov office of the Russian justice ministry declared Svobodnoye Slovo (Free Word), an NGO which publishes the independent newspaper Pskovskaya gubernia, a “foreign agent”.

The decision was made after an assessment of the organisation was conducted by the Pskov regional justice ministry department. It established that the organisation “receives money and property from another NGO which receives money and property from foreign sources”.

In addition, the statement said the NGO is running “political activities” because the newspaper is covering political issues.

Independent regional Pskovskaya Gubernia became well-known after a series of articles revealing Russian casualties in eastern Ukraine in the beginning of the Donbass conflict in the summer of 2014.

Azerbaijan: Editor sentenced to three months in jail for extortion

1 July 2016: Fikrat Faramazoglu, editor-in-chief of jam.az, a website that documents cases and arrests related to the ministry of national security, was arrested last Friday. He has been given a three-month sentence after being accused of extorting money by threats.

Faramazoglu’s wife said a group of three unidentified men showed up at their home, confiscating his laptop. Documents and even CDs from his children’s weddings were confiscated without any warrant. The three men informed Faramazoglu’s wife that her husband had been arrested.

Russia: Police detains Meduza freelancer covering death of children in Karelia

30 June 2016: Police detained Danil Alexandrov, a freelance journalist for Meduza news website working in Republic of Karelia reporting on the death of 14 children in a boating accident on Syamozero Lake. He was accused of working “without a license“.

Alexandrov was detained on his way out of the Essoilsky village administration building, where he spoke to the head of the town. The police reportedly approached Alexandrov and threatened to confiscate all his equipment unless he signed aan administrative offence report. He signed the document.

“They hinted that it might be necessary to confiscate ‘evidence of my journalistic activities’,” Alexandrov told Meduza, adding that the police insisted the publication was a foreign media outlet and had to be accredited by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Foreign Ministry’s rules on accreditation discuss full-time staff members of foreign media outlets but do not comment on freelancers. Alexandrov’s court case is scheduled for 6 July. He faces a maximum penalty of 1,000 rubles (€14) for working “without a license”.

2 Jun 2016 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

American academic Alexa Huang explores how Shakespeare’s plays were edited to make them more acceptable to Victorians.

Shakespeare has been used to divert around censorship, “sanitised” and redacted for children, young adults and school use, and even used as a form of protest all over the world. While censors have reacted differently to Shakespeare (sometimes with a blind eye), self-censorship (by directors and audiences) is part of the picture as well.

Not all censors work in the capacity of a public official. Many censors are in fact editors, writers and educators who are gatekeepers of specific forms of knowledge. Julius Caesar, for example, is often deemed one of the more appropriate plays to teach and perform in American school systems, because the themes of honor, free will and principles of the republic (as opposed to more sexually charged themes in other plays) are considered inspiring and suitable in the educational context.

The themes in such plays as Romeo and Juliet (teen exuberance and sex), The Merchant of Venice (anti-Semitism), Othello (racism and domestic violence), and Taming of the Shrew (sexism) make modern audiences uncomfortable, but they compel us to ask harder questions of our world.

While Shakespeare has been a large part of American cultural life, the “Shakespeare” that is taught and enacted in schools has often been redacted and even censored. But this is not a new phenomenon. The history of bowdlerized Shakespeare goes back to the nineteenth century. To bowdlerize a classic means to expurgate or abridge the narrative by omitting or modifying sections that are considered vulgar.

In fact, the term “bowdlerized” comes from Henrietta “Harriet” Bowdler who edited the popular, “family-friendly” anthology The Family Shakespeare (1807) which contains 24 edited plays. The anthology sanitised Shakespeare’s texts and rid them of undesirable elements such as references to Roman Catholicism, sex and more. The anthology was intended for young women readers.

Multiple ambiguities in Shakespeare are replaced by a more definitive interpretation. Ophelia no longer commits suicide in Hamlet. It is an accidental drowning. Lady Macbeth no longer curses “out, damned spot” but instead she says “Out, crimson spot!” Prostitutes are omitted, such as Doll Tearsheet in Henry IV Part 2. The “bawdy hand of the dial” (Mercutio) in Romeo and Juliet is revised as “the hand of the dial.”

Contrary to popular imagination, censorship is not a top-down operation. Instead, it is often a communal phenomenon involving both the censors and the receivers who willingly accept the Shakespeare that has been improved upon. Family Shakespeare was itself a family project. Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825) worked with his sister Henrietta Bowdler to bowdlerize or clean up the classics. The subtitle of the volume states that “nothing is added to the original text; but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.” Shakespeare is credited as the author, though Bowdler made clear the Bard needed quite some heavy-handed editing.

Ironically, Henrietta Bowdler was herself censored. Thomas Bowdler’s name appears on the cover. It took two centuries for Henrietta to be credited for the anthology, for obviously there is no way she could have admitted that she recognised the bawdy puns in Shakespeare, much less editing them out of Shakespeare. The Bowdlers are among the better-known “censors” in the nineteenth century who editorialised the classics including Shakespeare.

When laying out her editorial principles in the preface, Bowdler does not hesitate to criticise the “bad taste of the age in which [Shakespeare] lived” and Shakespeare’s “unbridled fancy”:

The language is not always faultless. Many words and expressions occur which are of so indecent Nature as to render it highly desirable that they should be erased. But neither the vicious taste of the age nor the most brilliant effusions of wit can afford an excuse for profaneness or obscenity; and if these can be obliterated the transcendent genius of the poet would undoubtedly shine with more unclouded lustre.

She further explains her motive in The Times in 1819, emphasising that the “defects” in Shakespeare have to be corrected:

My great objects in the undertaking are to remove from the writings of Shakespeare some defects which diminish their value, and at the same time to present to the public an edition of his plays which the parent, the guardian and the instructor of youth may place without fear in the hands of his pupils, and from which the pupil may derive instruction as well as pleasure: and without incurring the danger of being hurt with any indelicacy of expression, may learn in the fate of Macbeth, that even a kingdom is dearly purchased, if virtue be the price of acquisition

While censorship carries a negative connotation in our times, The Family Shakespeare did broaden Shakespeare’s audience and readership. While American schools continue to redact Shakespeare, they also infuse Shakespeare into the American cultural life in various forms.

Alexa Huang will be participating in the Index on Censorship magazine panel at the Hay Festival.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91322″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229008534812″][vc_custom_heading text=”Bowdler revisited: Shakespeare

” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229008534812|||”][vc_column_text]March 1990

Artist Jane Zweig discovers books burned in Boston and looks at how Romeo and Juliet has been censored in America.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94784″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532458″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censoring Shakespeare” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532458|||”][vc_column_text]September 1975

A Lithuanian stage producer was dismissed from his post after sending an ‘open letter’ to Soviet authorities protesting censorship in theatre.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93836″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228508533832″][vc_custom_heading text=”Clampdown on drama” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228508533832|||”][vc_column_text]November 2007

Livingstone Njomo Waidhura reports on drama taught in schools and whether Shakespeare is a suitable hero for Kenya. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2016 Index on Censorship magazine celebrates the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, looking at how his plays have been used around the world to sneak past censors or take on the authorities – often without them realising. Our special report explores how different countries use different plays to tackle difficult themes.

With: Jan Fox, György Spiró, Martin Rowson[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”86201″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/02/staging-shakespearean-dissent/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]