2 Dec 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What can’t people talk about? The latest magazine looks at taboos around the world”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

What’s taboo today? It might depend where you live, your culture, your religion, or who you’re talking to. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores worldwide taboos in all their guises, and why they matter. Comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects for laughs; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health; and Saudi Arabia’s first female feature-film director Haifaa Al Mansour speaks out on breaking boundaries with conservative audiences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”60px”][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Plus a crackdown on porn and showing your cleavage in China; growing up in Germany with the ghosts of WW2; what you can and can’t say in Israel and Palestine; and the argument for not editing racism out of old films. As the anniversary of Charlie Hebdo murders approaches, we also have a special section of cartoonists from around the world who have drawn taboos from their homelands – from nudity, atheism and death to domestic violence and necrophilia.

Also in this issue, Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see, Natasha Joseph interviews the Swaziland editor who took on the king and ended up in prison, and Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who lost their jobs after investigating presidential property deals in Mexico.

And in our culture section, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman looks at the power of music as resistance in an exclusive short story, which is finally seeing the light after 50 years in the pipeline. We have fiction from young writers in Burma tackling changing rules in times of transition, and there’s newly translated poetry written from behind bars in Egypt, amid the continuing crackdown on peaceful protest.

Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: WHAT’S THE TABOO? ” css=”.vc_custom_1483453507335{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Why breaking down social barriers matters

Stand up to taboos – Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel on how comedy tackles the no-go subjects

The reel world – Nikki Baughan interviews female film directors Susanne Bier and Haifaa Al Mansour, from Denmark and Saudi Arabia

Not just hot air – Kaya Genç goes inside Turkey’s right-wing satire magazine Püff

Slam session – Péter Molnár speaks to fellow Hungarian slam poets about what they can and can’t say

Whereof we cannot speak – Regula Venske on growing up in Germany after WWII

China’s XXX factor – Jemimah Steinfeld investigates a crackdown on porn and cleavage

Pregnant, in danger and scared to speak – Nina Lakhani and Goretti Horgan on abortion laws and social stigma in El Salvador and Ireland

Airbrushing racism – Kunle Olulode explores the problems of erasing racist words from books and films

Why are we whispering? – Alastair Campbell on why discussing mental illness still makes some people uncomfortable

Shouting about sex (workers) – Ian Dunt looks at the debate where everyone wants to silence each other

The history man – Professor Mohammed Dajani Daoudi explains how he has no regrets, despite causing outrage after taking Palestinian students to Auschwitz

Provoking Putin – Oleg Kashin on how new laws are silencing Russians

Quiet zone: a global cartoon special – Featuring taboo-busting illustrations from Bonil, Dave Brown, Osama Eid Hajjaj, Fiestoforo, Ben Jennings, Khalil Rhaman, Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Padrag Srbljanin, Toad and Vilma Vargas

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Reining in power – Natasha Joseph talks to the Swaziland editor who took on the king

Whose world are you watching? – Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see

Bloggers behind bars – Ismail Einashe interviews Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers

Mexican airwaves – Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who were shut down after investigating presidential property deals

Head to head – Bassey Etim and Tom Slater debate whether website moderators are the new censors

Off the map – Irene Caselli on how some of the poorest people in Buenos Aires fought back against Argentina’s mainstream media

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The rocky road to transition – Ellen Wiles introduces new fiction by young Burmese writers Myay Hmone Lwin and Pandora

Sounds of solidarity – Chilean author Ariel Dorfman presents his short story on the power of music as resistance

Poetry from a prisoner – Omar Hazek shares his verses written in an Egyptian jail and translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index on Censorship’s CEO, Jodie Ginsberg, on the pull between extremism legislation, free speech and terrorism

Index around the world – Josie Timms presents Index’s latest work and events

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Oct 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, mobile, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Following the conclusion of an Oct. 19 to 21, 2015 joint international emergency press freedom mission to Turkey, representatives of participating international, regional and local groups dedicated to press freedom and free expression find that pressure on journalists operating in Turkey has severely escalated in the period between parliamentary elections held June 7 and the upcoming elections.

The representatives also determine that this pressure has significantly impacted journalists’ ability to report on matters of public interest freely and independently, and that this pressure, if allowed to continue, is likely to have a significant, negative impact on the ability of voters in Turkey to share and receive necessary information, with a corresponding effect on Turkey’s democracy.

Accordingly, the representatives stand in solidarity with their colleagues in the media in Turkey and demand an immediate end to all pressure that hinders or prevents them from performing their job, or which serves to foster an ongoing climate of self-censorship. They also urge that steps be taken to ensure that all journalists are able to freely investigate stories involving matters of public interest, including allegations of corruption, the “Kurdish issue”, alleged human rights violations, armed conflict – particularly issues related to the ongoing conflict in Syria – and local or regional issues or policies.

Further, the representatives specifically urge authorities in Turkey:

- To conduct a complete and transparent investigation into violent attacks on journalists and media outlets, including recent incidents targeting Hurriyet and columnist Ahmet Hakan, and to ensure that impunity for violent attacks on journalists is not allowed to flourish.

- To end the abuse of anti-terror laws to chill reporting on matters of public interest or criticism of public figures, and to ensure that such laws are both precisely tailored to serve only legitimate ends and interpreted narrowly

- To reform laws providing criminal penalties for insult and defamation by dealing with such cases under civil law and to end all use of such laws to target journalists, particularly Art. 299, which provides Turkey’s president with heightened protection from criticism, in violation of international standards.

- To enact reforms to free state media outlets from political pressure, e.g., by effecting a transition to a public broadcasting service that presents information from plural and diverse sources.

- To end the use of state agencies, such as tax authorities or others, to apply pressure against journalists who engage in criticism or critical coverage of politicians or government actions.

- To end the practice of seeking bans on the dissemination of content related to matters of public interest, e.g., the ban on dissemination of information related to the recent bombings in Ankara, and the practice of seeking to prohibit satellite or online platforms from carrying the signals of certain broadcasters.

- To refrain from taking other steps to censor online content, such as the blocking of websites or URLs, or the blocking of social media accounts, absent a legitimate, compelling reason for doing so, subject to independent judicial oversight.

- To release all journalists imprisoned on connection with journalistic activity, and to immediately and unconditionally release VICE News fixer Mohammed Rasool, who remains behind bars despite the release of two British colleagues for whom he was working and with whom he was detained.

- To end all arbitrary detentions and/or deportations of foreign journalists.

- To respect the right of journalists to freely associate and to end pressure brought in recent years against the Journalists Union of Turkey.

The mission representatives also urge Turkey’s president:

- To end all exercises of direct personal pressure on owners and/or chief editors of critical media.

- To stop using negative or hostile rhetoric targeting journalists.

- To accept the greater degree of criticism that comes with holding public office, to stop using criminal insult or defamation provisions to silence critics, and to publicly call on supporters to refrain from seeking to initiate such cases on his behalf.

Moreover, the mission representatives urge foreign governments, particularly those of the United States and countries within the European Union:

- To press Turkey to uphold its commitments to respect and uphold international human rights standards and, in the case of the EU, to ensure that any concessions granted in connection with resolution of the ongoing refugee crisis are made consistent with a long-term strategy specifically designed to encourage Turkey to comply with its commitments to uphold international human rights standards.

Finally, the mission representatives urge journalists in Turkey:

- To avoid the use of negative or hostile rhetoric targeting other journalists and to strive to uphold ethical standards developed by or as the result of self-regulatory bodies or processes.

- To exercise greater solidarity with colleagues under pressure and to defend the rights of all journalists.

Markus Spillmann, IPI Executive Board Vice Chair

Barbara Trionfi, IPI Executive Director

Steven M. Ellis, IPI Director of Advocacy and Communications

Muzaffar Suleymanov, Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) Europe and Central Asia Program Research Associate

Erol Onderoglu, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Representative

Patrick Kamenka, Journalist, Intl. Federation of Journalists/European Federation of Journalists (IFJ/EFJ)

Mustafa Kuleli, Turkish Journalists Union (TGS) Secretary General; Member IFJ/EFJ

David Diaz-Jogeix, Article 19 Director of Programmes

Melody Patry, Index on Censorship Senior Advocacy Officer

Ceren Sozeri, Ethical Journalism Network (EJN) Member; Galatasaray University Associate Professor

2015 JOINT INTERNATIONAL EMERGENCY PRESS FREEDOM MISSION TO TURKEY – FACT SHEET

From Oct. 19 to 21, 2015, representatives of the International Press Institute (IPI), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), Index on Censorship, Article 19 and the Ethical Journalism Network (EJN) conducted a joint international emergency press freedom mission to Turkey.

The mission was conducted with the support and assistance of the Journalists’ Union of Turkey (TGS) and IPI’s National Committee in Turkey, with representatives of both groups also joining the mission.

The mission was conducted in light of deep concerns over the deteriorating state of press freedom in Turkey and its impact both on the upcoming Nov. 1 parliamentary elections and beyond. Its primary goals were to demonstrate solidarity with colleagues in the media in Turkey, to focus attention in Turkey and abroad on the impact that growing pressure on independent media is likely to have on the ability to hold a free and fair election, and to push for an end to such pressure.

Specific concerns related to, among other developments, physical attacks on journalists and media outlets; raids on media outlets and seizures of publications; threatening rhetoric directed at journalists; the increasing use of criminal insult and anti-terrorism laws targeting independent media and government critics; the ongoing imprisonment of journalists; deportations of foreign journalists; and decisions by satellite and online television providers to stop carrying signals of broadcasters critical of the government.

During the course of meetings in Istanbul and Ankara, mission participants heard from representatives from nearly 20 different major media outlets in Turkey. They also met with representatives of three of the four parties currently holding seats in Turkey’s Grand National Assembly: the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

Organisers sought to meet with representatives of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), but were not afforded an opportunity to do so. Similarly, organisers sought meetings with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s spokesperson and foreign policy adviser, but received no response.

At the close of the mission, participants conducted a dialogue forum bringing together representatives from a broad cross section of media in Turkey for an open discussion to share with them the participants’ experience in Ankara meeting with foreign diplomats and representatives of political parties, and to hear the media representatives’ concerns and suggestions for how international organisations can best support press freedom and free expression in Turkey.

About the Participants

The International Press Institute (IPI) is a global network of editors, media executives and leading journalists dedicated to furthering and safeguarding press freedom, promoting the free flow of news and information, and improving the practices of journalism.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is an independent, non-profit organisation that works to safeguard press freedom worldwide.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is a non-profit organisation which defends the freedom to be informed and to inform others throughout the world.

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) is a global union federation of journalists’ trade unions that aims to protect and strengthen the rights and freedoms of journalists.

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) is a branch of the International Federation of Journalists.

Article 19 is human rights organisation that fights for the protection of freedom of expression and access to information, particularly protecting those that dissent.

Index on Censorship is an international human rights organisation that promotes and defends the fundamental right to freedom of expression and campaigns against censorship.

The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN) promotes ethics, good governance and independent regulation of media content.

The Journalists Union of Turkey (TGS) is the affiliate in Turkey of the International Federation of Journalists and the European Federation of Journalists.

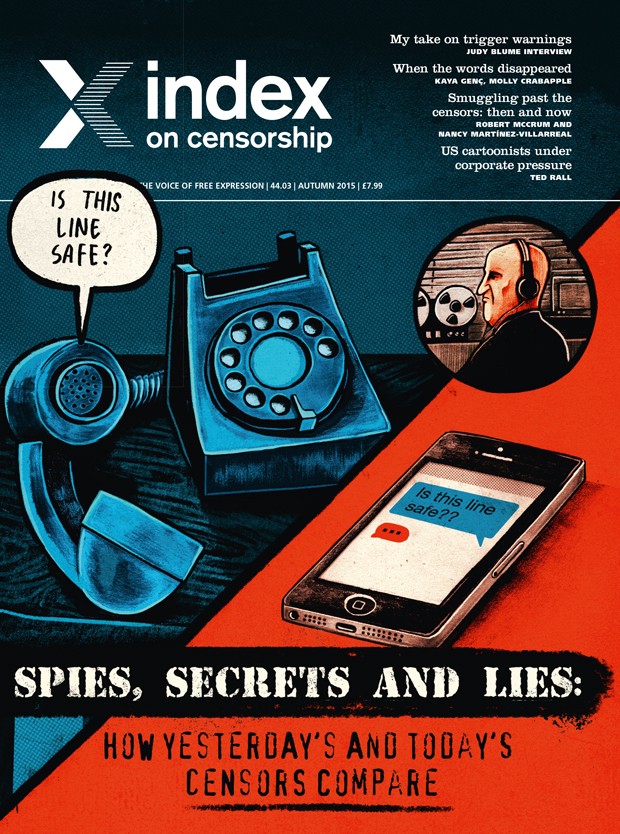

16 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

Judy Blume (Photo: Elena Seibert)

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

“Why did you kill the pet turtle?” The question took author Judy Blume by surprise on a recent US book tour. The child asking it was referring to a novel first published in 1972, Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, where Dribble, the pet turtle, is accidentally swallowed by the protagonist’s younger brother. “I’d never heard that complaint before,” Blume told Index on a recent trip to the UK. “People found it funny before, but now I can expect animals-have-feelings-too complaints. Those sorts of questions strike you as funny, but it’s awful too. It’s the adults behind them that are the problem.”

Blume, who has sold 80 million books and been translated into 32 languages, has nothing against turtles, or indeed children’s attachment to pets. But she talks of the “new, very protective” approach to reading that she is seeing more and more. “It’s the job of a parent to help children deal with unexpected things that happen,” said the Florida-based writer, best known for her teen titles. “I often get letters saying, ‘We didn’t like it when this thing happened in your book, so we’re not going to read any of them again.’”

By tackling coming-of-age issues, including sex and puberty, she has experienced various cries of outrage along the way, as well as outright bans by some schools and libraries. In 2009, her publisher even had to send her a bodyguard, after she was deluged with hate-mail and threats for speaking out in support of Planned Parenthood, a US pro-choice group. Five Judy Blume books feature in the 100 most frequently challenged list (1990 to 1999), compiled by the American Library Association, which tracks attempts to ban or censor literature, often by US school boards.

Like many people, I grew up with Judy. I was 11 by the time I had devoured most of her back catalogue. I remember a battered paperback of Forever – the infamous teen sex novel – being passed around my class like contraband, although all our parents and teachers must have known we had it. Her writing about periods was far more enlightening than anything we were taught at school. I still remember the nurse who came into our class and frightened the hell out of us by waving a super-size tampon in the air. “My mum has those!” one school friend said proudly. Her mum was French. I was sure mine didn’t mess with such things.

A US website, Flavorwire, recently compiled a list of “awkward Judy Blume moments” from people’s youth. There was one where a local librarian lent her eight-year-old grandson the novel about a girl’s first period and he wept at the sheer horror of it. There was another about a nine-year-old who had a public tantrum and screamed “Censorship!” at the top of her voice when told she was “not ready” for Judy. Perhaps the most enlightening, however, was the person who admitted trying to get Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret removed from the library because she thought it questioned the existence of God. “I didn’t read it until years later, far past the time when my fundamentalism had lapsed,” she confessed, inadvertently playing a part in the long tradition that sees the most vocal criticism of books coming from those who haven’t read them.

“I’ve always said censorship is caused by fear,” Blume told Index, while on tour to launch her latest book In the Unlikely Event. As a board member of the National Coalition Against Censorship in the US, she has long spoken with passion about her views on the freedom to read, and against books being censored.

Among the most recent children’s books to be targeted in the US are Jeanette Winter’s The Librarian of Basra and Nasreen’s Secret School, which are based on true stories from Iraq and Afghanistan, respectively. Parents from Florida’s Duval County created a petition in July to object to the books references to Islam and war.

“I don’t use age ratings. There’s no reason why someone who wants to, can’t read it. I don’t believe in saying books are for certain age groups,” said Blume, when asked, at a recent UK event at King’s Place, London, if she thought her newest book, written for adults, should be restricted to readers of a certain age.

If censorship had an agony aunt, it would be Blume. Throughout her long career, she’s tackled the big issue openly and without judgement. “Am I being a censor?” a mother asked her recently, after confessing she omitted a section of Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing when she read it to her children. It was a segment where a father is left in charge of his two sons and makes a real hash of it by not knowing how to handle them. “The mother decided not to read that part to her own boys, because she didn’t want them to know how other dads are,” said Blume. “That’s your choice. But my advice is read it all. Talk about it, laugh about it. Say: ‘Aren’t we glad our dad is different?’ No, it’s not censorship. It’s your decision. But are you going to do them any favours by trying to protect them?”

And then comes the thing that makes Blume “very, very upset”: trigger warnings. These are cautions put on books or reading lists to warn of potentially upsetting content, and they are becoming a growing practice at US colleges. Blume only came across the term recently, but instantly took it very seriously. “Why do college students need to be warned that what they are about to read might make them feel bad? These are 20-year-olds, but they need a professor to warn them? What kind of education is that? It makes me crazy.”

The author, who was listed by the US Library of Congress in the living legend category of writers and artists in 2000, also expressed concern about hearing of writers being “dis-invited” from US schools and universities for things they have written or said. “This can be over one incident in a 400-page book,” she said. “I thought the idea of education was to exchange ideas and discuss. How we learn from one another?” Nonetheless, she’s optimistic that this fearful attitude can be fought against. She has already seen professors and teachers standing up to it.

One thing Blume adamantly doesn’t want to see is a return to 1980s America, which was the worse period she has witnessed for freedom to read, and when controversial books were stripped out of classrooms. She believes there has been a return from the precipice of the Reagan era, yet there are still attempts to exert too much control. She referred, very enthusiastically, to The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, which has also caused a stir and was pulled from the curriculum in Idaho schools. What’s the problem with it I ask? “The language, the sexuality, all things related to life as a teenage boy. It’s like saying it’s a bad thing to be a teenage boy!”

“It’s the kids’ right to read,” she said resolutely as our conversation came to a close and she prepared to continue her whirlwind tour. It’s a mantra she’s been repeating for decades. At 77 and still as dynamic as ever, she shows no sign of stopping anytime soon.

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.