11 Jan 2019 | Awards, Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. The Museum of Dissidence

2018 Freedom of Expression Awards at Metal, Chalkwell Park, Essex.

Artistic freedom is under attack in Cuba, but artists are fighting back. Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, members of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Cuban artist collective the Museum of Dissidence, along with many others, are putting themselves on the line in the fight against Decree 349, a vague law intended to severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

“349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and is also an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “Artists, in a spectacular way, must work in a state of double resistance, as artists and as activists, because the system has control over all opportunities for artistic growth.”

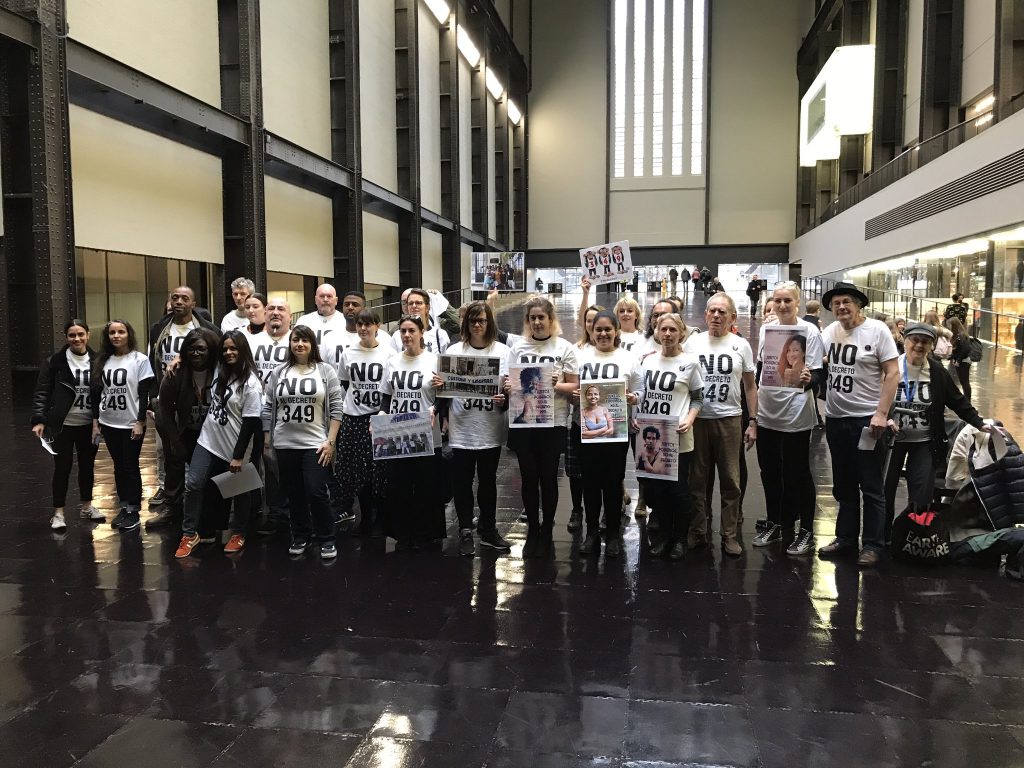

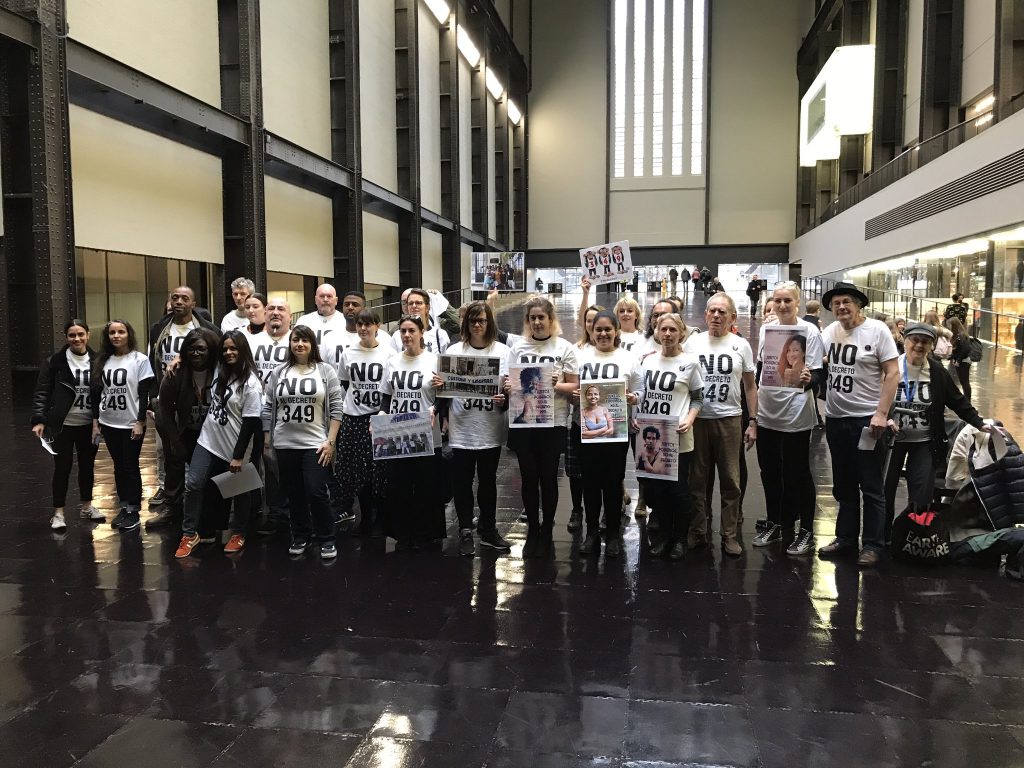

For their role in peacefully protesting Decree 349, Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva were among 13 artists arrested, including Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, in Havana on 3 December 2018. Index joined others at the Tate Modern in London on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those jailed.

Protest in support of jailed Cuban artists at the Tate Modern gallery, London, October 2018.

On Human Rights Day on 10 December 2017, US Assistant Secretary of State Kimberly Breier tweeted: “[O]ur minds turn to the people of #Cuba, who have endured decades of repression and abuse at the regime’s hands, most recently via the creativity-crushing #Decree349.”

“The international help is positive because it makes visible the abuses of the Cuban regime against the people, but I think we must sacrifice ourselves in body and spirit — in a peaceful way — if we want to achieve our freedom,” Nuñez Leyva tells Index on Censorship. “We are very grateful for any help and pronouncements against 349. The redaction of the decree and the silence of the authorities is demonstrating that in Cuba there is a dictatorial regime in which no type of political, economic or social opening is taking place.”

In the days following all arrested artists were released, although they remained under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas at the time told the Associated Press that changes would be made to Decree 349 but failed to open a dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree. A version of the law came into force on 7 December.

“We are determined to continue demanding the full repeal of 349,” Nuñez Leyva says. “We do not want to continue living in this perennial state of vulnerability.”

The persecution of the Museum of Dissidence isn’t limited to arrests. On 9 November Otero Alcántara took to Facebook to call out a campaign to discredit him. State security had been sending texts and holding meetings with his neighbours in what the artist said was a “desperate attempt” to “sabotage our activities”.

“The rhetoric that the government uses is well known to all — that we are mercenaries — and although most people no longer believe it, some of them decide to exclude you because you are a ‘marked’ person like you have a contagious disease,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “You are a socially excluded and politically persecuted.”

“We try all the time not to give it too much importance, we try to smile because we really do not want to feel any bad energy,” he adds. “Our principle is love, dialogue, peaceful struggle. If they wish to defame us, it is on their conscience, not ours.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Nuñez Leyva describes the efforts to dissuade Cuban artists from protesting 349 — including the seizure of anti-349 t-shirts emblazoned with three wise monkeys when re-entering Cuba after attending the Creative Time Summit in Miami — as “a mechanism to prevent the spread of the truth and above all, to make us tired and to resort to leaving the country”. But the Museum of Dissidence will not be deterred. “To achieve that, they will have to be more vicious.”

“The government spends innumerable resources to repress any type of expression that makes it uncomfortable,” Otero Alcántara says. “It seeks to discredit activists and artists all the time by isolating them from society, from their friends, from their family.”

After a seven-month campaign to attain visas to enter the UK — which saw the Museum of Dissidence denied visas on three occasions, causing them to them miss the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards ceremony in April 2018 — Nuñez Leyva and Otero Alcántara were finally able to receive their award at Metal Culture, an arts centre in Chalkwell Hall, Southend-on-Sea, on 18 October 2018. The artists were in residence at Metal for two weeks in October as part of their partnership with Index on Censorship.

“Southend-on-Sea generously gave us all its warmth. Staff at Metal, the uncharacteristically warm climate, the brick architecture of the place, the low tide river, the local legends told by a science fiction writer, the banks that paid homage to the deceased, the interest of the local media in the Cuban cause were encouraging for us,” Nuñez Leyva says. “To realise that a calm, inclusive city is possible opens us up and make us less naive when going back to face the Cuban reality.”

Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara as Miss Bienal

During his time in the UK, Otero Alcántara performed in Trafalgar Square on 26 October as Miss Bienal, a character he created in 2016 to symbolise the mulatto woman typified in clichés by tourist and for artistic consumption.

“Entering the National Gallery in a rumba dress without censorship made us realise the context of freedom and acceptance of difference that is breathed in London,” he says. “London is a giant city with so much art, diversity and history, it makes the body detoxify a bit from the bad energy you get living in a system like the Cuban one.”

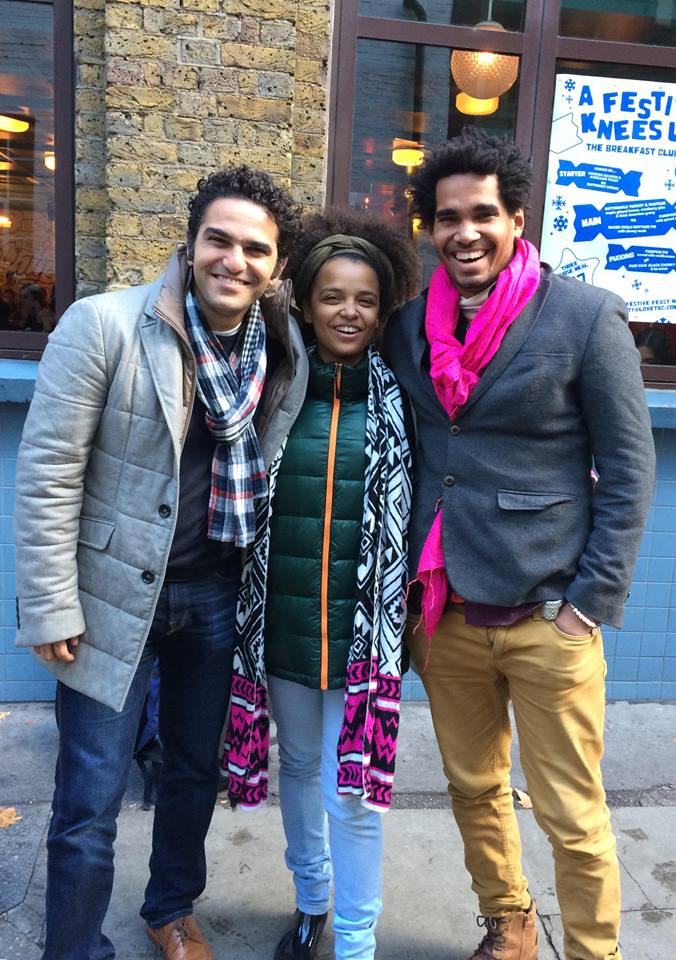

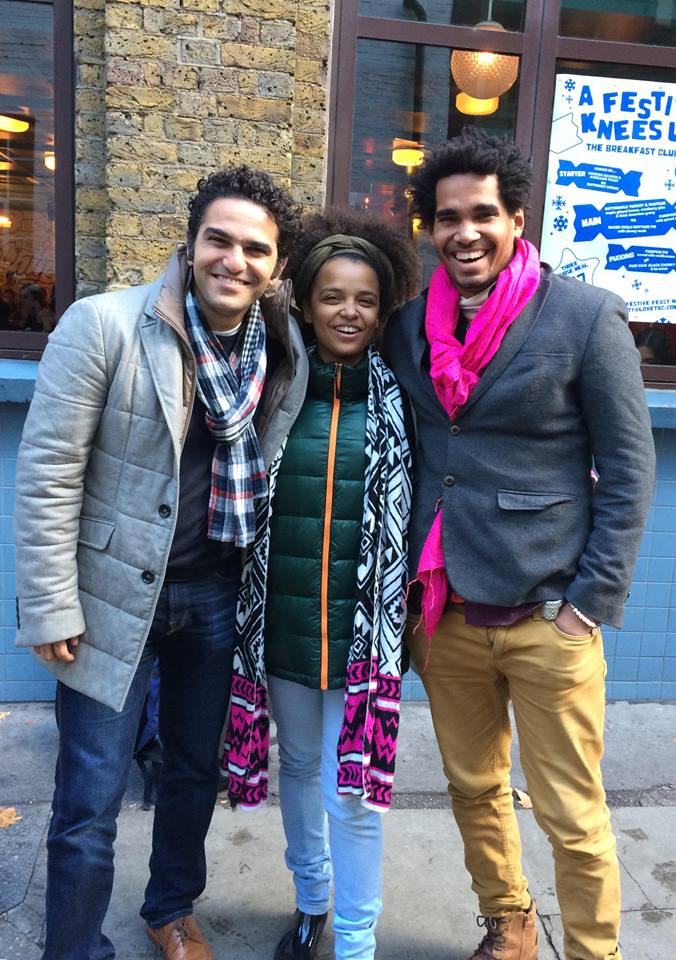

Mohamed Sameh with Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara in London

While in London, the pair met with Mohamed Sameh, co-founder and international relations advisor at the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning. ECRF is one of the few remaining human rights organisations in Egypt, a country that often uses its struggle against terrorism as a justification for its crackdown on human rights.

“We shared with Mohamed the desire for prosperity in our respective countries, but also the smile that we shared, which we hold on to all the time,” Nuñez Leyva says. “The contagious smile of Mohamed is similar to that of, not only of the Museum of Dissidence in Cuba, but also Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Coco Fusco, Student without Seed, Michel Matos, Aminta D’Cardenas, La Alianza, Yasser Castellanos, Veronica Vega, Javier Moreno, Tania Bruguera, and other artists who at this moment are fully engaged in the improvement of Cuba.”

“Although our contexts are different, we feel a total empathy with the struggles of Mohamed, because in our work we put ourselves at risk all the time for our rights and total freedom of expression, principles that for Mohamed are also non-negotiable.” [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1547483905239-0a56285c-5eb0-10″ taxonomies=”23707″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jan 2019 | Artistic Freedom, Artists in Exile, News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Özgül Arslan

“It turned into a place where it became impossible to breathe,” says feminist visual artist Özgül Arslan about Turkey. “Everything and everywhere changed. Nothing was familiar anymore. Everything that makes up the country’s memory is being sold, demolished and destroyed one by one.”

Arslan grew up in a Turkey marred by the 1980 coup d’etat, when the Turkish military overthrew the government following violence between left- and right-wing factions. Though some say military rule helped stabilise Turkey, which changed prime ministers 11 times in the 1970s alone, the military arrested hundreds of thousands of people and executed dozens more. Others were tortured or just disappeared — all for their activism, opinions or work.

Arslan, and many others living in Turkey, learned how to remain silent for their own safety. It was this period of silence that drew Arslan to art. With its metaphors and hidden messages, it gave Arslan a voice.

But even now, Turkey is growing increasingly illiberal under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Erdogan has taken control of media, diminished the opposition party, and restricted freedom of expression by imprisoning journalists and human rights activists. The president has also restricted the role of the parliament and prime minister, allowing himself to legislate by decree.

Socially, the situation is just as grim. Erdogan has spoken of creating a “pious generation,” one which adopts traditional Islamic values. This trend is seen in education, with religious schools receiving more funding than secular schools, despite having less students. In 2017, secular schools were forced by the government to remove evolution from the curriculum, which was seen as the government’s conservative and religious ideology infiltrating schools. The government defended the changes, saying the new curriculum would be both nationalist and moral.

The government has also condemned feminism, with Erdogan saying in 2014 that women and men were not equal. Arslan said that women are taught to be chaste at every opportunity. Furthermore, Arslan is a part of the Alevi faith, a minority sect of Islam. Arslan says there has always been problems for people of the Alevi faith, but now the Erdogan is pressuring everybody not of the majority Sunni faith.

“It is meaningless to live in a country where the government is constantly uttering threats. It makes our lives, our humanity and our minds lose their worth,” Arslan said.

She didn’t want to raise her daughter in this kind of environment, so she and her husband moved to London in 2016.

Arslan, who has done exhibitions both in Turkey and abroad, spoke to Leah Asmelash from Index on Censorship about censorship of the arts in Turkey, how her beliefs affect her work and upcoming projects. [/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”104410″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://ozgularslan.com/catharsis-circle/”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index: How old were you when you first started creating art? What drew you to it?

Arslan: Since I was born until I was 11-years-old I lived in Erzincan, a city in eastern Turkey located within an earthquake zone. We sometimes used to stay in a tent put up on a land near our house for our safety. There would be no paper nor paints, we only took with us the most basic supplies necessary for living. Whenever we would enter to our house, which we called shelter, or go out of it, we would run. There would always be something of a construct and reconstruct around me when I was growing up. What I made at the time were – I could only define it long afterwards – “land art” experiments. I would draw on earth, rocks, branches, water, snow, ice, crops, etc. anything you could think of. I would give them shape, interfere with their natural cycle, reorganize them, then observe the changes they would undergo and the entire process of it… This was a kind of game I played with nature. I used to do and nature would undo again what I made. I have produced this type of ecologic artworks during my first years at university.

These were times when we were caught between tradition, faith and parents who would keep silent and teach their children to remain silent like them after the 1980 military coup. I always wanted to make art, but what drew me into it was art’s metaphorical and ironic narrative using symbols. It was a path I chose intentionally to record the process of defining myself and what was happening around me.

Index: Your art typically has political messages. When did your art become political? Was it a response to things happening around you?

Arslan: When I was studying at university, I would often hear that it wouldn’t be easy for a woman to make art. There was a lot of gender discrimination in art as everywhere else. The exact same struggle I was giving against my family, society or the state stood right in front of me in the world of art. The mere fact of continuing working with the belief that it is possible to make art anywhere, with anything and under any condition was a political stance in itself.

Domestic violence, child abuse, the insignificance of being a woman, privation, deficiencies in education, discriminations based on identity, etc. Any of these issues related to this region is my past… What is personal is political. As an artist, I chose to express my relationship with the present and my questioning through my work. Even though I can’t really tell if there was a defining moment, there has always been a latent political content in all my artistic works.

In short, I wanted to create a visual language consisting of personal and social codes and references to question the relationship between public space, home and modernity.

Index: Much of your work features different mediums, including painting, photos and videos. Why have you chosen to use such differing mediums?

Arslan: I mainly studied literature, philosophy and art history. I was an avid reader and I also used to draw. I used to paint on canvas during my high school years and afterwards. I worked for a painting gallery and for an architecture firm that would also make decorations. I learned a lot of things there that would have been impossible to learn at school. I also worked with painters, studied painting and acting. Murals I made during my university years in internal spaces and outdoors, the different techniques I have tried while working on walls and through my work with materials such as glass helped me to understand what decorativeness corresponded to technically and in terms of content.

Although the first conceptual works date back to 1965, because those did not have a continuity, we can set the starting date of contemporary art production in Turkey in the end of the 1980s. The military coup of 1980 played a significant role in it. But art was still affected by the negative influences stemming from the domination of Turkish modernism and the tradition of painting attached to it. One of the results of this conservative influence was that art institutions would not give an opportunity to young artists.

As someone who started making art works at the end of the 1990s, the core of my influences from photography to video and from using manufactured articles to painting are the Dada movement in 1920s and the conceptual arts that started developing in the 1960s. By using various medium and developing new techniques, I have adopted a multidisciplinary construct in which the content of the project was determinant.

This also included my choice of spaces. With the Internet becoming a part of our life, I have also sought with my work to define the field and how we would position ourselves in it. When conceiving the form, essence and content of my artistic works, I usually try to work in public spaces other than art galleries and organize the space in a way that has a bond with what I want to produce.

I chose the medium either according to the content and to the space after conducting my research and reading on a certain concept and questions that arise from a given situation or totally based on my intuition. This can either be an object, a manufactured article, a photograph or a video, or I may also develop a new technique different from the traditional ones by using other medium befitting to the content.

Index: You come from an Alevi background, which is considered heresy by the by the dominant form of Islam, and Alevis face a lot of persecution in Turkey. People have said that Erdogan is trying to make Turkey more Sunni. How is freedom of religion diminished in Turkey, and how are you affected by that?

Arslan: In 1993, radical Islamists staged an arson attack on the Madımak Hotel in Sivas where intellectuals who came to attend an event in the city from across Turkey were staying, because they were Alevis and atheists. Thirty-three intellectuals and two hotel workers were killed in the attack. The subsequent trial dropped due to statute of limitations. Today, those who were defending that disaster sit in important positions in the government.

As you say, Alevis have always been under pressure but freedom of belief is no longer a problem unique to Alevis in Turkey. It is the problem of seculars altogether. Conservatives are trying to put everyone else under pressure to be and live like them. When 20 or 30 years ago it was the secular way of life which was imposed on everyone, it’s now conservatives who are exerting the same pressure. Nothing has changed or improved in the life of Alevis, they still feel themselves forced to hide their identity.

Part of society who wants to see modern and rational policies and move forward is facing a group ruling – or wanting to be ruled – with ignorance. It is meaningless to live in a country where the government is constantly uttering threats. It makes our lives, our humanity and our minds lose their worth. Some of our friends have been deprived of their freedoms or their jobs just because they have pronounced words such as “freedom” and “peace.”

Index: Your work commonly features women and comments on sexism within society. Why is that message important to you? How does your identity as an Alevi woman impact your perspective and thus the art you create?

Arslan: There are too many issues concerning women’s rights. There is a predominant patriarchal discourse at home, at work, at school and anywhere you can think of. There are cultural codes embedded in society through state and religion. Those are constantly telling us what we can or we cannot do, how we should obey, how we should love, what we should wear and even what we should eat. We are fighting for our human rights every day, even with our closest ones. I consider myself as a feminist artist. Since I make art through my personal references as a woman, an artist, a teacher and a mother of a girl, women, children and all the marginalized are my problem too.

I see myself lucky for being born in an Alevi family, despite being socially marginalized and subject to a degrading discourse. Alevi families traditionally raise their children with freedom of belief. They respect everyone’s beliefs because of their own faith. Moreover, there is no prohibition of representation and statues like in conservative Islam.

Being raised in an Alevi family allowed me to notice at an early age social discriminations based on identity, state and religious policies, people who were marginalized and marginalization in general and to develop a sensibility on these issues.

Index: As Turkish society grows increasingly conservative, how are artists being silenced?

Arslan: Every dissenting, marginal opinion is being finger-pointed as a target by the government. Artists are being discredited. Either their artistic works are censored or artists themselves exercise self-censorship.

In the past years, galleries in the center of Istanbul were attacked by mobs with batons and stones because people were allegedly drinking alcohol – actions we call “pressure from the neighbourhood.” Those galleries either moved or closed. No one claimed responsibility and no legal action was initiated against anyone over the incidents. There has been attacks targeting certain exhibited pieces in different events. Some artworks were removed. Not only they don’t understand contemporary art, but they are also pointing the fingers at the artistic work on this field through disdainful social media comments or statements relayed pro-government publications. By doing so, they turn these artists into a target for their supporters.

No artistic event whose content doesn’t back the government’s discourse or which is traditionally aligned with it can get funding or financial support. Many theatres were closed, buildings housing art schools and conservatories were emptied. Academics at schools were either dismissed or reassigned somewhere else. A lot of statues in public spaces were removed and no one really knows what happened to them. Others were subject to attacks and damaged by radical Islamists. Works of art were called “monstrosity” by the authorities. A large number of historical artefacts restored by government supporters who had no experience have been irreparably damaged. Buildings with an important historical and artistic significance, such as the Atatürk Cultural Center in Istanbul, were demolished. The parliamentary speaker ordered actresses during a theatre performance to get out of the stage and the play continued without any woman acting. Several restrictions were brought to performing arts under state institutions such as theatre and ballet.

Index: How has this silencing affected the way you work and what you produce?

Arslan: Part of my work has been influenced by social movements. This led me to question art and work on new techniques – which I shared with my students. But in the last few years, the way I presented my work was much stronger as a result of what we have been through. I have tended to render apparent what used to be covered up by using an aesthetic language.

Index: What motivated you to leave Turkey?

Arslan: It turned into a place where it became impossible to breath. Everything and everywhere changed. Nothing was familiar anymore. Everything that makes up the country’s memory is being sold, demolished and destroyed one by one. Nature got its share too. Rivers, streams, lakes, forests, lands owned by the treasury, cultural heritage sites, the air, water, the soil, seeds… So much has been sacked.

Those who speak up against it are arrested in their house in the middle of the night and kept in jail for months without an indictment. They otherwise lose their jobs.

“Either you have to keep silent or you will leave.” Think a President who threatens half of the population with the other half that elected him. We have recently witnessed a number of bomb attacks, we were subject to tear gas almost every day and we became used to walk between water cannons and armed riot police.

They took children from their schools to events held by a pro-government foundation or the directorate of religious affairs without asking the permission of their families.

Turkey has turned its back to science. Entire curriculums were changed. Many qualified teachers were dismissed. The country is rapidly verging to Dark ages in the hands of a government looking to raise a “religious and rancorous” generation.

The number of sexual attacks and violence against children and women is very high. While the “man” who perpetrates this crime can get a reduction of sentence for good behaviour in court, the fact that a woman wore a mini skirt or went outside late at night can be used as a justification for “provoking” him. If the laws don’t protect women and children, they also give women lectures of chastity at each opportunity. The government is aggressively discrediting the discourse of feminists. What we call “the pressure from the neighbourhood” is now a reality everywhere.

As a feminist family, we didn’t want to raise our daughter with a conservative education which is not based on science. Personally speaking, I preferred to move where I could work more freely and keep developing my art without exercising self-censorship rather than sitting back and watching everything.

There are a lot of modern families who left Turkey and stopped their careers to move in other countries. These are families who don’t want to force their children to live under this dark regime. Especially secular white collars are leaving Turkey.

As writer Tezer Özlü once said, “This not our country, but the country of those who want to kill us.”

Index: Now that you’re based in London, how do you think this change in location will affect your art, if at all?

Arslan: My art studio is in Turkey. Most of the artwork I have produced and my materials are also there. My conditions of work are changing and my production is limited. I am trying to live and continue producing with my meagre means. I also follow the artistic production here and learn about the processes of production.

After moving here, I opened one solo exhibition in Istanbul and took part in group exhibitions. Being invited in group exhibitions here as well is a great satisfaction and keeps me motivated to produce more works. Artists and curators I have worked with in London are very understanding and open to communication and sharing.

Although I am far from Turkey in terms of distance I still follow what happens day. I continue thinking and reading about being subject to everyday violence. Although I define myself as a “voluntary migrant”, I started to focus on the links between voluntary migration and violence and oppression. The artworks I am producing here follow this direction.

Index: How is your art, with its feminist messages, received in Turkey versus internationally? Is there a difference and if so, why do you think that is?

Arslan: The audience in London knows a lot about art. They can therefore read your work very easily. I needed to make less explanations to the public in London than what I used to do in Turkey. Generally speaking, the audience here has extensive knowledge about art, they are interested in feminism or other political issues and better equipped to empathize. My methods of productions are methods or metaphors they are familiar with. The themes of my artworks are not only issues we are confronted in Turkey but current universal issues we are facing.

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”104411″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://ozgularslan.com/exposure-maruz/”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index: Sanat yapmaya başladığınızda kaç yaşındaydınız? Sizi sanat yapmaya çeken neydi?

Arslan: Doğduktan sonra onbir yaşına kadar ki sürecim Türkiye’nin doğusunda bulunan şehirlerden biri olan ve deprem bölgesinde yer alan Erzincan’da geçti. O yüzden güvenlik nedeniyle bazı dönemlerde haftalarca evimizin yakınındaki arazide, sadece çadırda kalmamız gerekirdi. Kağıt, boya malzemeleri yoktu, sadece yaşamsal zorunluluğu olan malzemleri yanımıza alırdık. O zamanlarda ev, sığınak dediğimiz yere ise koşarak girip koşarak çıkardık. Etrafımda hep bir “yapı kurumu”(construct) ve “yeniden yapım”(reconstruct) vardı. O zaman ürettiklerim daha çok sonradan tanımını koyabildiğim “Land art” denemeleriydi. Toprak, taş, dal, su, karlı arazi, buzlar, ekinler vs. aklınıza ne gelirse üzerine çizmek, şekil vermek, onların var olan döngüsüne müdahale etmek, düzenlemeler yapmak ve sonrasında geçirdikleri değişimi, süreci gözlemlemek… Bu bir çeşit doğayla oyun oynamaktı, ben yapardım o da tekrar değiştirirdi. Üniversitenin ilk yıllarında bu tip ekolojik çalışmalar ürettim.

Gelenek, inanç ve 1980 darbesi nedeniyle susulan, çocuklarına kendileri gibi sessiz kalmayı öğreten veliler arasında geçen dönemlerdi. Sanat yapma isteğim hep vardı ancak en çok da sanatın kodlarla, metaforik ve ironik anlatım yönü beni sanata itti. Kendimi ve çevremde olup bitenleri tanımlama sürecimi kayıt altına almak için bilinçli olarak tercih ettiğim bir yoldu.

Index: Eserlerinizde genellikle siyasi mesajlar görmek mümkün. Sanatınız ne zaman politik hale geldi? Etrafınızda olup bitenlere karşı bir cevap mıydı bu?

Arslan: Üniversite yıllarımda bir kadının sanat yapmasının pek de kolay olmayacağının altı sık sık çiziliyordu. Kadın ayrımı her yerde olduğu gibi sanatta da vardı. Aile, toplum ve devletle verdiğim kimlik mücadelesi sanat ortamında da karşımdaydı.Her yerde, her şeyle ve her şartta sanat yapılır anlayışıyla çalışmalarımı devam ettirmem de politik bir tavırdı.

Aile içi şiddet, çocuk olarak uğradığınız tacizler, kadın olarak hiç bir değerinizin olmaması, yokluk, eğitimdeki eksiklikler, kimlik ayrımları vs. Bu coğrafyanın sorunu olan her şey benim de geçmişim…Kişisel olan politiktir. Ben de bir sanatçı olarak var olan durumla ilişkimi, sorgulamalarımı, çalışmalarımla ifade etme yöntemini seçtim.

Kesin zaman verememekle birlikte sanırım çalışmalarımda gizli politik bir içerik hep vardı.

Özetle, kamusal alan-ev-modernite ilişkisini ve politikalarını sorgulayan, kişisel ve toplumsal kodlara referanslarla bir görsel dil oluşturmak istedim.

Index: Çalışmalarınızın önemli bir kısmında resim, fotoğraf ve video gibi farklı sanatsal araçlar başvurmanız dikkat çekiyor. Neden birbirinden farklı medyumlar kullanmayı tercih ettiniz?

Arslan: Ağırlıklı olarak edebiyat, felsefe, sanat tarihi dersleri aldım. İyi bir okuyucuydum ve resim yapardım. Lise yıllarımda ve sonrasında tuval yapım ve yerel resim galerisinde, daha sonra da dekorasyon yapan bir mimarlık şirketinde çalıştım. Okulda öğrenmenin olanaksız olduğu çok şey öğrendim. Aynı zamanda ressamlarla da çalıştım ve akademik desen, resim ve oyunculuk eğitimi aldım. Üniversite yıllarımda, dış ya da iç mekanlara yaptığım duvar resmi, denediğim duvar üzeri farklı teknikler ve cam gibi malzemelerle yaptığım işler sayesinde dekoratif olanın, hem içerik hem de teknik olarak neye karşılık geldiğini kavradım.

Türkiye’de güncel sanat üretiminin 1965 yılında ilk kavramsal çalışmalar yapılmış olsa da süreklilik gösteremediği için 1980’lerin sonlarında başladığını öne sürebiliriz ve bunda 1980 darbesinin büyük rolü var. Bu dönemde Türk modernizmi ve ona bağlı pentür geleneğinin sanat alanındaki hakimiyetinin olumsuz etkileri devam etmekteydi. Bu muhafazakar etkilerden biri sanat kurumlarının genç sanatçılara yer vermemesiydi.

1990’ların sonunda üretimine başlamış biri olarak, 1920’lerde Dada ve 1960’lardan itibaren gelişen kavramsal sanat, fotoğraftan videoya, hazır nesneden resme uzayıp giden eğilimlerimin kökenini oluşturuyor. Çok sayıda medyumu bir arada kullanarak ve yeni teknikler geliştirerek projenin içeriğinin belirleyici olacağı çok disiplinli bir yapıyı benimsedim.

Buna mekan seçimlerim de dahil oldu. İnternetin hayatımıza girmesiyle birlikte alanı nasıl tanımlayacağımıza, içerisinde nasıl konumlanacağımıza dair yaptığım çalışmalarım da oldu. Sanat galerileri dışında kamusal alanlarda çalışmaya ve çalışmalarımda biçim-öz-içerik oluştururken mekanın üretilecek işle bağını kuracak şekilde kurgularım.

Sezgisel olarak yada bir durumun sonucunda oluşan bir kavram ve sorular hakkında okuma ve araştırmalarımı yaptıktan sonra, kullanılacak medyumu içeriğe ve mekana göre belirlerim. Bu bir obje, hazır nesne, fotoğraf-video olabiliyor ya da geleneksel tekniklerin ve medyumların dışında içeriğe uygun bir teknik geliştiririm. Kişisel sergilerimde dahi sergide yer alacak her bir çalışmayı mekanda yerleştirilecek düzenlemenin bir elemanı gibi kurgular ve üretirim. Dışarıdan içeriye, içeriden dışarıya bir referans, hemen hemen tüm çalışmalarımda vardır.

Index: Alevi bir aileden geliyorsunuz. Alevilik, İslam’da heretik olarak görülüyor ve Türkiye’de de Alevilere yönelik yoğun baskılar var. Erdoğan’ın Türkiye’yi Sünnileştirmeye çalıştığı belirtiliyor. Türkiye’de din ve inanç özgürlüğü ne kadar daraldı ve siz bundan ne şekilde etkileniyorsunuz?

Arslan: Muhafazakarlar, Sivas’ta Madımak Oteli’nde 1993 yılında bir etkinlik için toplanan Türkiye’nin farklı yerlerinden gelen aydınları, Alevi ve Ateist oldukları gerekçesiyle yaktılar. 33 Aydın ve 2 otel görevlisini hayatını kaybetti. Dava zaman aşımına uğradı. Şimdi o felaketin savunucuları şu anda yönetimde söz sahibi makamlardalar.

Belirtiğiniz gibi Alevilere karşı bir baskı hep var ancak günümüz Türkiye’sinde inanç özgürlüğü sorunu sadece artık Alevilerin sorunu olmaktan çıktı. Bu artık tüm sekülerlerin sorunu. Muhafazakarlar kendilerinden olmayan kerkesi, kendileri gibi olmaları ve yaşamaları için her alanda baskı altına almaya çalışıyorlar. Bundan 20-30 yıl önce seküler yaşam tarzi herkese dayatılırken şimdi muhafazakar kesim bu baskıyı yapıyor. Alevilerin hayatında gelişen veya değişen bir şey yok, hala kimliklerini gizlemek zorunda kalabiliyorlar.

Çağdaş akılcı yöntemleri görmek ve ilerlemek isteyen bir kesimin karşısında cahilce kararlarla yöneten ve yönetilmek isteyen bir kesim var. Sürekli size tehtitler savuran bir yönetimin içinde yaşamak anlamsız. Hayatımızı, insanlığımızı, aklımızı değersizleştiriyor. “Özgürlük”, “barış“ gibi kelimeleri sırf telaffuz ettiler diye koca bir toplumun önünde bazılarımız özgürlüklerinden ya da işlerinden edildiler.

Index: Çalışmalarınızda yaygın olarak kadınlara ve toplum içindeki cinsiyet ayrımcılığına yer veriyorsunuz. Bu mesaj sizin için neden önemli? Alevi bir kadın olmak bakış açınızı ve sanatınızı nasıl etkiliyor?

Arslan: Kadınların hakları konusunda çok fazla sorun var. Evde, işte, okulda aklınıza gelebilecek tüm alanlarda ataerkil söylem hakim. Bize sürekli nerede ne yapacağımızı ve ne yapamayacağımızı, nasıl itaat etmemiz, nasıl sevmemiz, nerede ne giymemiz, ne yememize kadar söyleyen devlet ve din yoluyla toplumda yer etmiş kültürel kodlar var. Her günümüz, insani haklarımız için en yakınlarımızla dahi mücadele etmekle geçmekte. Ben feminist bir sanatçıyım, kişisel referaslarımla ürettiğim için bir kadın, sanatçı, öğretmen ve bir kız çocuğu annesi olarak doğal olarak kadınlar, çocuklar ve tüm ötekileştirilenler benim de meselem.

Türkiye’ de sosyal olarak ötekileştirmeler, hakaret niteliği taşıyan söylemlere maruz kalmış olsam da Alevi bir ailede dünyaya gelmiş olmam konusunda kendimi şanslı görüyorum. Alevi aileler çocuklarını inanç özgürlüğüyle yetiştirirler ve inançları gereği herkesin inancına saygı duyarlar. Ayrıca muhfazakar İslamdaki gibi suret ve heykel yasağı yoktur.

Alevi bir ailede büyümüş olmam topkumdaki kimlik ayrımcılıklarının, devlet ve din politikalarını, öteki olmak, ötekileştirmeleri erken yaşta fark etmemde ve bu konuda duyarlılık geliştirmemde faydası oldu.

Index: Türkiye’de toplum giderek muhafazakârlaştıkça, sanatçılar nasıl susturuluyor?

Arslan: İktidar tarafından muhalilif, marjinal her düşünce hedef gösterliyor. Sanatçılar ve üretimleri itibarsızlaştırılıyor. Üretilen çalışmalar ya sansürleniyor ya da sanatçılar otosansür uyguluyor.

Galeriler, geçtiğimiz yıllarda İstanbul’un merkezinde mahalle baskısı uygulanarak içki içiliyor gerekçesiyle bir grup tarafından taşlı sopalı saldırıya uğradılar. Galeriler oradan ya taşındı ya da kapattılar. Hiç kimse bu olayda sorumluluk almadı ve kimseye hukuki bir işlem yapılmadı. Bazı sergilenen çalışmalara, farklı etkinliklerde saldırılar oldu ya da eserler kaldırıldı. Çağdaş sanat çalışmalarını anlamadıkları gibi bu alanda yapılan çalışmaları küçümseyecek yazılarla sosyal medya ya da iktidara ait yayınlarda açıklamalar yaparak kendi yandaşlarına açık açık hedef göstermekteler.

Geleneksel veya içeriksel olarak kendi söylemlerini desteklemeyen hiç bir sanat etkinliğine fon-maddi destek ayrılmıyor. Tiyatroların çoğu kapatıldı, sanat, koservatuar okullarının binaları boşaltılıyor. Okullarda akademisyenler ya görevlerinde alındı ya da görev yeri değiştirildi. Kamusal alandaki pek çok heykel kaldırıldı, akıbetlerinin ne olduğu belli değil. Yine kamusal alandaki heykellere muhafazakar kesim tarafından saldırıldı, zarar verildi. Sanat eserleri iktidar tarafından “Ucube” olarak nitelendirildi. Bu iktidar dönemi sırasında işi bilmez iktidar yanlılarına yaptırılan pek çok tarihi eser, restorasyon sırasında geri dönüşü olanaksız zararlara uğradı. Tarihi ve sanatta önemli bir yere sahip bazı binalar yıkıldı, “Atatürk Kültür merkezi” bunlardan biri. Meclis başkanı bir tiyatro gösterisinde kadın oyuncuları sahneden indirdi, kadınlar olmadan gösterim yapıldı. Devlete bağlı tiyatro, bale gibi gösteri sanatlarına pek çok gösterim sınırlamaları getirildi…

Index: Bu susturma çabaları çalışmanızı ve sanatsal üretimlerinizi nasıl etkiledi?

Arslan: Sosyal hareketlerden etkilenerek ürettiğim çalışmalarımında aynı zamanda sanatın sorgusunu yaparak yeni yöntemler üzerinde çalışıyor ve eğitimci yanımla da öğrencilerimle paylaşıyordum. Son yıllarda yaşadıklarımızın etkisiyle çalışmalarımdaki sunumlar da sertleşti. Örtbas edileni estetik dille görünür kılmaya yöneldim.

Index: Türkiye’den neden ayrılmaya karar verdiniz?

Arslan: Nefessiz kaldığınız bir yer oldu artık. Her şey her yer değişti. Hiç bir yer tanıdık değildi. Ülkenin belleği tek tek satılıp,yıkılıp yok ediliyor. Doğa da nasibini aldı, nehirler, dereler, göller, ormanlar, hazine arazileri, kültür miras alanları, hava,su, toprak, tohum…pek çoğu talan edildi.

Buna karşı ses çıkaranlar gecenin bir vakti evlerinden alınıyor ve aylarca bir iddianame hazırlanmadan içerde tutuluyor veya işinden edilebiliyor.

Ya susup boyun eğeceksin ya da gideceksin” Bir başkan düşünün ki kendisini seçen %50 ile diğer %50’ yi tehtit ediyor. Son zamanlarımızda sürekli bir yerlerde bombalar patlıyor, neredeyse her gün biber gazına maruz kalıyorduk, tomaların, çelik zırhlı polislerin arasında yürüyorduk.

Çocuklar ailelerinin izni alınmaksızın ders saatlerinde okuldan alınarak İktidar yanlısı bir vakfın ya da diyanetin düzenlediği toplantılara götürülebiliyor.

Türkiye bilime sırtını döndü, tüm müfredatlar değiştirildi. Nitelikli pek çok eğitimci görevinden edildi. “Dindar ve kindar” bir nesil yetiştirmek isteyen bir iktidarın elinde hızla orta çağ karanlığına doğru gitmekte.

Çocuklar ve kadınlara çok fazla cinsel saldırı ve şiddet söz konusu. Bu suçu işleyen “erkek” mahkemede kıravat taktığı için iyi hal indirimi alabiliyorken, kadın ya da çocuk kısa etek giydiği, gece dışarıda olduğu için gibi oldukça anlamsız gerekçeler de ağır tahrik sebebi olabiliyor. Yasalar kadınları ve çocukları korumazken, her fırsatta kadınlara iffetli olma dersleri veriliyor. Hükümet Feministleri hedef gösterici tavırla itibarsızlaştırarak söylemlerinin altını boşaltıyor.

Mahalle baskısı sessiz bir şekilde her yerde.

Biz feminist bir aile olarak kızımızın bilimden uzak, muhafazakar bir eğitimle yetişmesini istemedik. Ben de çalışmalarımı daha özgürce devam edebileceğimi, kendime otosansür uygulamayacağım, sanatımı geliştirebileceğimi düşündüğüm için ve tüm olup bitene seyirci kalmak, hiç bir şey yapamayarak orada olmaktansa taşınmayı tercih ettim.

Bizim gibi Türkiye’den ayrılıp, kariyerlerini bırakıp başka ülkelere taşınan çok fazla çağdaş düşünen aile var. Çocuklarını bu karanlık düzene mahkum etmek istemeyen aileler. Seküler kesimin özellikle beyaz yakalıları ülkeyi terk etmekte.

Yazar Tezer Özlü’nün dediği gibi “Burası bizim değil, bizi öldürmek isteyenlerin ülkesi”

Index: Artık Londra’da yaşıyorsunuz. Bu mekân değişikliğinin sanatınızı etkileyecek mi ya da etkilerse, sizce nasıl etkileyecek?

Arslan: Atölyem Türkiye’de, çalışmalarımın ve atölye malzemelerim de çoğu orada. Üretimimde var olan şartlar değişiyor, produksiyonum sınırlı, kısıtlı imkanlarımla üretmeye ve yaşamaya çalışıyorum. Burada üretilenleri takip ediyorum, üretim süreçleri ve işleyişlerini öğreniyorum.

Buraya geldikten sonra İstanbul’da bir solo sergi ve grup sergilerine katıldım. Burada da grup sergilerine davet almış olmam sevindirici, üretmem için iyi bir motivasyon sağlıyor. Londra’da çalıştığım sanatçılar, ve küratörler oldukça anlayışlı, iletişime ve paylaşıma açıklar.

Türkiye’den lokasyon olarak uzakta olsamda hala oraya ait meseleleri takip ediyorum. Her gün Şiddete (“Everyday Violence”) maruz kalmamız üzerine düşünüyorum ve okumalar yapıyorum. Her ne kadar ben “ gönüllü göçmen” statüsünde tanımlansam da zorunlu ve ya gönüllü göçün şiddet ve zulumle bağını odağıma aldım. Burada ürettiğim çalışmalarım bu doğrultuda ilerlemekte.

Index: Sanatınız ve verdiğiniz feminist mesajlar Türkiye’de nasıl karşılanıyor? İki ülke arasında bir fark görüyor musunuz ve, varsa eğer, neden kaynaklandığını düşünüyorsunuz?

Arslan: Burada ki sanat izleyicisi oldukça donanımlı haliyle çok rahat okuma yapıyorlar. Turkiye’de yaptığımdan daha az açıklama yapmam yeterli oldu diyebilirim. Genel olarak sanat izleyicisini bilgi yelpazesi geniş, feminist ya da diğer politik meselelerle ilgili bilgi sahibiler o yüzden empati kurabiliyorlar. Üretim metedodlarım aşina oldukları yötemler ve metaforlar. Çalışmalarım salt Türkiye’de karşımıza çıkan meseleler de değil, güncel ve uluslararası arenada da örneklerini gördüğümüz konular.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”104413″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://ozgularslan.com/silencia-silence/”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1546851612980-bd13bbff-a326-1″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]