31 Oct 2017 | Azerbaijan, Belarus, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Media Freedom, Montenegro, News and features, Russia, Serbia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Since 2004, over 700 journalists have been killed for their reporting. Nine out of 10 of these cases go unpunished.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform verified a number of reports of impunity since it began monitoring threats to press freedom across Europe in May 2014. Reporters Without Borders also tracks cases of violence against journalists in its annual press freedom barometer and its end-of-year round-up of journalists killed worldwide.

“The brutal murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia on 16 October is a stark reminder of the dangers journalists face for reporting in the public interest. Pressure must be brought to bear on government officials in all countries to ensure that crimes against journalists do not go unpunished,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Mapping Media Freedom, said.

Impunity, which is defined as the exemption from punishment or paying reparation for a crime, goes hand-in-hand with authorities’ inaction when investigating both violent and nonviolent actions against journalists.

“Violence against journalists and impunity for their attackers has become all too common in many parts of the world, and alarmingly, is on the rise in Europe, particularly in cases of journalists investigating corruption. We reiterate our call for the creation of a UN Special Representative for the Safety of Journalists to address this vicious cycle”, said Rebecca Vincent, UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders.

To condemn such crimes, increase accountability and defend the rights of media professionals, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 2 November as the ‘International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists’ in 2013. It has since been observed to raise awareness of impunity and condemn violence against the media.

AZERBAIJAN

Azerbaijani journalist Afgan Mukhtarli

On 29 May 2017, investigative journalist and government critic Afgan Mukhtarli disappeared on his way home in Tbilisi, Georgia. Mukhtarli reappeared the next day across the border in Azerbaijan and was accused of illegal border crossing, resisting police and smuggling when police allegedly found €12,000 on his person. He was immediately sentenced to three months in pre-trial detention.

This case is unique in that it is the first cross-border operation alleged to be accompanied by the Georgian government. Azerbaijani lawmaker and a member of the Parliament Human Rights Committee Elman Nasirov claimed Mukhtarli’s kidnapping was “the most successful operation carried out in recent years”. Nasirov also accused him of being a member of a broader anti-Azerbaijan network. As a preventive mechanism, Nasirov claimed that Azerbaijani special forces made necessary arrangements with Georgian special forces.

Police have questioned political activists, members of opposition parties, and journalists as part of the investigation. Sevinc Vagifqizi, a freelance reporter, was detained while waiting outside the state border services where Mukhtarli was being held. Other journalists who have been questioned in the case of Mukhtarli are investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who is facing a travel ban despite her release from jail, and more recently, Aytac Ahmadova.

The circumstances of Mukhtarli’s arrest were also notable for the suspicious injuries he sustained. Outside of his abduction, Mukhtarli’s lawyer reported that he had suffered a broken nose, multiple bruises and a possible broken rib.

BELARUS

On 12 March 2017, Adarya Hushtyn, the editor for BelaPAN news agency, arrived from Minsk to the town of Orsha in the Vitsebsk region of Belarus to cover a protest against the tax on the unemployed which was to be held in the early afternoon.

When she arrived that morning, she was stopped at the railway station by the commander of the riot police squad to check her documents and press card. She was then detained by police officers together with Nasha Niva newspaper correspondent Siarhei Hoodzilin who had arrived to cover the same protest.

At the police station, both journalists were searched and informed that they were being checked for in the database of wanted people. Hushtyn was detained at the police station for nearly three hours without any explanation. She was only released after the protest she intended to report on was over.

Hushtyn filed a complaint against her illegal detention and was told that she was mistaken for another woman who was also wanted by the police. As it turned out, this woman was not only unlike the journalist but was found two weeks prior to Hushtyn’s detention. She also filed an application to the prosecutor’s office to initiate a criminal case under Article 198 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus “preventing from lawful professional activity of a journalist”, but was refused.

In March 2017, the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) made an appeal to the Minister of Home Affairs calling on the authorities to investigative the mass violations of journalists’ rights. The reply was that police officers did not violate any law and that BAJ “has to stop ‘covering up’ and ‘justifying’ the people who have nothing to do with mass media”.

In March alone, 94 reporters were detained and 6 were beaten by the police while covering nationwide protests.

CZECH REPUBLIC

In April 1992, Václav Dvořák was shot and killed in front of his home. Dvořák was a journalist who uncovered information regarding František Mrázek, a controversial Czech entrepreneur once believed to be the boss of the Czech mob. Dvořák both published his reports locally or passed them along to national distributors. There are thirteen other murders thought to be linked to Dvořák’s.

After more than fourteen years, police identified Dvořák’s killer as gangster Bohuslav Hájek, who is believed to have been ordered by Mrázek to carry out the murder. However, Hájek disappeared in 2001 and it is believed that he was also murdered as an inconvenience and a witness to Mrázek’s operations.

GERMANY

On 6 July 2017 in Hamburg, Germany, police assaulted a number of journalists at the G20 protests.

Of the 35 investigations launched, 27 are accusations of assault perpetrated by police officers. At this time, none of the attackers have been arrested or convicted.

“There has been no police brutality,” Olaf Scholz, the mayor of Hamburg, claimed days after the protests during a televised interview.

On 8 July 32 journalists had their accreditation revoked by federal police without explicit reasoning. This launched an investigation by federal police, who discovered police files against the journalists contained incorrect information. Although there were errors made in police documents, it is unclear if the journalists have regained accreditation.

Journalists who lost accreditations include photographer Björn Kietzmann, Rafael Heygster (Weser Kurier), photographer for Junge Welt, Willi Effenberger Alfred Denzinger (Beobachter News), photographer Chris Grodotzki (Spiegel Online), Adil Yigit (Avrupa Postasi), editor Elsa Koester (Neues Deutschland) and freelance photographer Po Ming Cheung.

HUNGARY

On 15 July 2016 investigative journalist Csaba Móricz was insulted and then chased by the mayor of Érpatak, Orosz Mihály Zoltán, in a car. Earlier that day, Móricz went to Érpatak to document a city council meeting where he expected to ask questions to the mayor regarding a series of financial irregularities that he had uncovered.

At the beginning of the council meeting, instead of opening, the mayor launched into a fifteen-minute speech about the journalist, declaring him a “media rat” and “secret agent” several times, insinuating that Móricz lied about the financial situation in Érpatak for money. Two men then entered the room, one of which was Richárd Fügedi, a councillor of the far-right party Jobbik. One of the men then started threatening the journalist and asked: “Are you going to push me, Mr Móricz?“

The journalist left and drove away from the meeting, but soon realised that his vehicle was being followed by a group of three other cars – two of which belonged to the mayor‘s office. All cars involved were driving above the speed limit towards a nearby town when the journalist noticed a police patrol and decided to stop and ask for protection.

The police officers, instead of protecting the journalist, checked Móricz’s ID in the midst of a group of five people, including Mayor Zoltán and a second Jobbik MP. The group filmed the incident despite the journalist requesting they stop when his personal details, including his home address, were read aloud. Móricz had to insist to the police officers that they escort him to safety after initially being refused.

Just one month later, the authorities have opened an investigation against Móricz for breaking the speed limit. The investigation began when the website he works for wrote that he had to speed up to 140-150 km/h to escape his followers.

ITALY

Cosimo Cristina was born in Termini Imerese, an industrial village not far from Palermo, in 1935. He started working in the local newspaper L’Ora di Palermo when he was twenty. Later, he became a freelance contributor for several national newspapers and for the ANSA news agency.

In the late 1950’s, Cristina started to collect information about the clans of the Cosa Nostra, or the Sicilian mafia, in Palermo and Termini Imerese. In 1959 he published a new magazine titled “Prospettive Siciliane” (Sicilian Perspectives) with his friend Giovanni Capuzzo to cover stories on the mafia. This is when he started receiving death threats.

On 3 March 1960, he did not return home from work. Two days later, his corpse was discovered near to the railway, his skull broken. In his pockets he carried an ID and two letters; one for his fiancé and one for Capuzzo. In these letters Cristina begged for forgiveness for taking his own life. For the police it was a suicide and the case was closed. There was no further investigation or handwriting analysis on the letters found at the scene.

Five years later, police officer and expert on the Sicilian mafia Angelo Mangano began a new investigation. He knew Cristina had written several articles probing into the world of the Cosa Nostra. Mangano requested an autopsy on the corpse but the results confirmed the suicide, despite the doubts.

MALTA

Daphne Caruana Galizia

On 16 October at around 3pm, Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed when the car she was driving exploded in Bidnija in what is thought to have been a targeted attack. Galizia filed a police report 14 days prior saying that she was being threatened.

“The barbaric murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia is an attack on journalism itself. This crime is meant to intimidate every investigative journalist,” said Dr Lutz Kinkel, managing director of the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom.

“Because prime minister Joseph Muscat and parts of Malta’s political elite were targets of Galizia’s disclosures, we strongly recommend an independent investigation of this case. The killers have to be found and put on trial.”

On 17 October, Galizia’s family filed an application to Magistrate Consuelo Scerri Herrera to abstain from investigating the case because of the court’s “flagrant conflict of interest”. Galizia and the magistrate share a history of conflict and critique.

Galizia has conducted numerous high profile corruption investigations and has been subject to dozens of libel suits and constant harassment. Because of her research, in February, her bank assets were frozen following a request filed by the economic minister.

Galizia has made numerous opponents in the Maltese government and business world and has investigated and linked such high officials as opposition leader Adrian Deliato offshore accounts and alleged prostitution, real estate investment owner Silvio Debono to public land takeover and Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and his wife to hiding payments from Azerbaijan.

London: Vigil for Daphne Caruana Galizia

Join us to mark the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists by joining a vigil mourning the death of Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was murdered on Monday 16 October.

When: Thursday 2 November 1-2pm

Where: Malta High Commission, Malta House, 36-38 Piccadilly, Mayfair, London W1J 0LE (Map)

MONTENEGRO

On 1 November 2007 Tufik Softic, a Montenegrin journalist and reporter for the opposition daily newspaper Vijesti, was brutally beaten in front of his home in Berane by two hooded assailants wielding baseball bats. About six years later in August 2013, an explosive device was thrown into the yard of Softic’s family home. It was not until 2014 and broad international pressure on Montenegro that both cases began formally investigating.

On 17 July 2014, police arrested two men in the town of Budva under the suspicion of involvement in the attacks against Softic. After questioning by the state prosecutor, who also confiscated their passports, the men were released on the same day.

Ten years after the initial attack in February 2017, Softic filed a lawsuit against the state for ineffective investigation. The lawsuit claims that the state is responsible for mental pain and fear which Softic suffered and will suffer because of the danger of re-attack, the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro reported. The state, TUMM continued, “encouraged attackers by ineffective investigation and eventually, its ending”.

After years of stalemate, Softc initiated the trial for compensation for non-pecuniary damage related to human rights violations. He has since been awarded €7,000 as compensation for the ineffectual investigation and mental suffering he endured, becoming the first in Montenegro’s history to do so. Softic’s case is emblematic of the atmosphere of impunity in Montenegro and the broader Balkan region.

RUSSIA

Yulia Latynina (Twitter)

After multiple life-threatening attacks, Yulia Latynina fled Russia. The columnist, contributor and writer works for independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, as well as radio station Echo Moskvy.

“I have left Russia in connection with threats to my life,” Latynina wrote on Twitter on 10 September. A week before on 3 September, her car was set on fire and completely destroyed. On July 2017 the journalist’s car and parent’s house were sprayed with noxious gas which led to the poisoning of eight people in the surrounding area. In a third incident on August 2016, faeces were poured onto Latynina while she was on her way to work at Echo Moskvy station.

In all three cases, a proper investigation was not carried out and the perpetrators were not found.

Also in Russia, on 9 March 2016, an attack was made on a minibus carrying journalists and human rights activists, near the border between Ingushetia and Chechnya. After no suspects had been identified, the investigation was suspended in February 2017. Although Ingushetia resumed the investigation after a public backlash, no progress has been made.

SERBIA

Three controversial murder cases from the nineties and early 2000’s remain unresolved in Serbia, with the most well-known case being the murder of journalist and newspaper publisher Slavko Ćuruvija outside of his apartment in Belgrade in 1999. It is believed that the order came from senior secret service officials during the regime of strongman Slobodan Milošević. Four former state security officials have been on trial for the murder as of December 2014, which continues to progress slowly. The lack of closure to the case after nearly two decades shows the perpetuation of state impunity in Serbia even after regime change.

The suspicious death of journalist Dada Vujasinović in 1994 also remains unsolved. Vujasinović is believed to have been murdered because of her published articles regarding war criminal Željko Ražnatović, better known as Arkan. She was found dead in her apartment in 1994. The police ruled it a suicide and nobody has been arrested or prosecuted to this day.

The third case is that of Večernje Novosti journalist Milan Pantić, who was murdered in 2001. He reported on criminal affairs and official corruption. As of June 2017, the police investigation had finally been completed and suspects have been identified, awaiting a trial. All three of these cases are being investigated by an independent commission established in 2013.

UKRAINE

Pavel Sheremet (Photo: Ukrainska Pravda)

Journalist Pavel Sheremet‘s killing in a car bombing in Ukraine’s capital city on July 20, 2016, cast a chill over the country’s press corps, and the ongoing impunity for those behind the crime has continued to affect journalists’ ability to cover sensitive subjects.

Sheremet was killed when the car he was driving exploded in Kyiv. In a statement, Ukrainian police said that an explosive device detonated at 7.45am as Sheremet was driving to host a morning programme on Radio Vesti, where he had been working since 2015.

The car belonged to Sheremet’s partner, journalist Olena Prytula, who co-founded Ukrainska Pravda with murdered journalist Georgiy Gongadze.

Sheremet had been imprisoned by Belarusian authorities in 1997 for three months before being deported to Russia. Though stripped of his citizenship in 2010, he continued to report on Belarus on his personal website. He moved to the Ukrainian capital in 2011 to work for the newspaper Ukrainska Pravda.

There have been no arrests in the journalist’s murder.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”80577″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/bloc-notes/Impunita-dei-crimini-contro-i-giornalisti-una-scelta-politica”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

696 è il numero esatto di professionisti dell’informazione uccisi dal 2007 ad oggi nel mondo, secondo i dati raccolti dal Comitato per la Protezione dei Giornalisti (CPJ).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96211″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/targeting-journalists-name-national-security/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified over 3,600 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

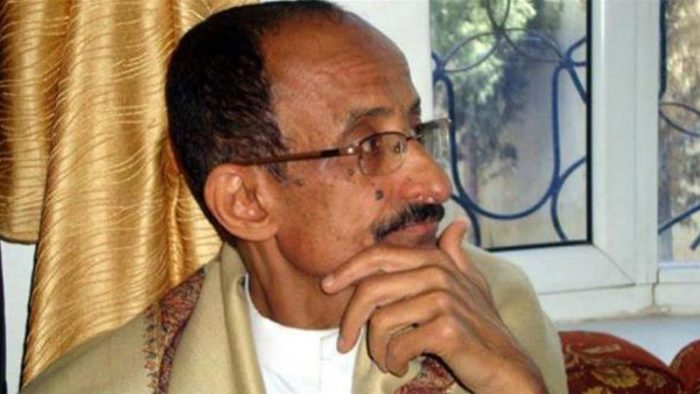

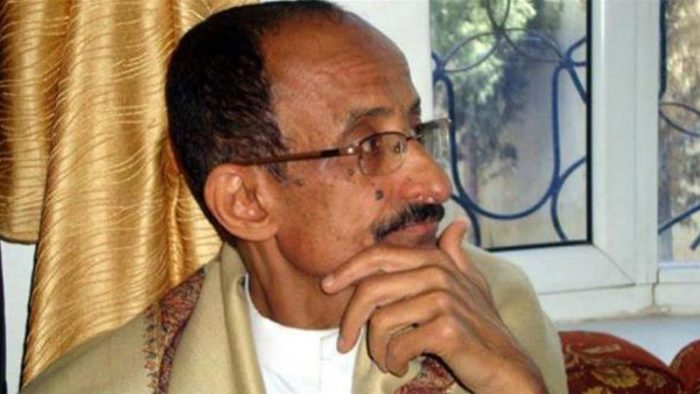

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]