5 Sep 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Hague, 5 September 2017

Dear members of the International Association of Prosecutors members, executive committee and senate,

In the run-up to the annual conference and general meeting of the International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) in Beijing, China, the undersigned civil society organisations urge the IAP to live up to its vision and bolster its efforts to preserve the integrity of the profession.

Increasingly, in many regions of the world, in clear breach of professional integrity and fair trial standards, public prosecutors use their powers to suppress critical voices.

In China, over the last two years, dozens of prominent lawyers, labour rights advocates and activists have been targeted by the prosecution service. Many remain behind bars, convicted or in prolonged detention for legal and peaceful activities protected by international human rights standards, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Azerbaijan is in the midst of a major crackdown on civil rights defenders, bloggers and journalists, imposing hefty sentences on fabricated charges in trials that make a mockery of justice. In Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkey many prosecutors play an active role in the repression of human rights defenders, and in committing, covering up or condoning other grave human rights abuses.

Patterns of abusive practices by prosecutors in these and other countries ought to be of grave concern to the professional associations they belong to, such as the IAP. Upholding the rule of law and human rights is a key aspect of the profession of a prosecutor, as is certified by the IAP’s Standards of Professional Responsibility and Statement of the Essential Duties and Rights of Prosecutors, that explicitly refer to the importance of observing and protecting the right to a fair trial and other human rights at all stages of work.

Maintaining the credibility of the profession should be a key concern for the IAP. This requires explicit steps by the IAP to introduce a meaningful human rights policy. Such steps will help to counter devaluation of ethical standards in the profession, revamp public trust in justice professionals and protect the organisation and its members from damaging reputational impact and allegations of whitewashing or complicity in human rights abuses.

For the second year in a row, civil society appeals to the IAP to honour its human rights responsibilities by introducing a tangible human rights policy. In particular:

We urge the IAP Executive Committee and the Senate to:

- introduce human rights due diligence and compliance procedures for new and current members, including scope for complaint mechanisms with respect to institutional and individual members, making information public about its institutional members and creating openings for stakeholder engagement from the side of civil society and victims of human rights abuses.

We call on individual members of the IAP to:

- raise the problem of a lack of human rights compliance mechanisms at the IAP and thoroughly discuss the human rights implications before making decisions about hosting IAP meetings;

- identify relevant human rights concerns before travelling to IAP conferences and meetings and raise these issues with their counterparts from countries where politically-motivated prosecution and human rights abuses by prosecution authorities are reported by intergovernmental organisations and internationally renowned human rights groups.

Supporting organisations:

Amnesty International

Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice, Benin

Anti-Corruption Trust of Southern Africa, Kwekwe

Article 19, London

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

Asia Justice and Rights, Jakarta

Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact, Chiang Mai

Asian Human Rights Commission, Hong Kong SAR

Asia Monitor Resource Centre, Hong Kong SAR

Association for Legal Intervention, Warsaw

Association Humanrights.ch, Bern

Association Malienne des Droits de l’Homme, Bamako

Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law Enforcement, Kyiv

Associazione Antigone, Rome

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House in exile, Vilnius

Belarusian Helsinki Committee, Minsk

Bir-Duino Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek

Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, Sofia

Canadian Human Rights International Organisation, Toronto

Center for Civil Liberties, Kyiv

Centre for Development and Democratization of Institutions, Tirana

Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights, Moscow

China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, Hong Kong SAR

Civil Rights Defenders, Stockholm

Civil Society Institute, Yerevan

Citizen Watch, St. Petersburg

Collective Human Rights Defenders “Laura Acosta” International Organization COHURIDELA, Toronto

Comunidad de Derechos Humanos, La Paz

Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, Lima

Destination Justice, Phnom Penh

East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project, Kampala

Equality Myanmar, Yangon

Faculty of Law – University of Indonesia, Depok

Fair Trials, London

Federation of Equal Journalists, Almaty

Former Vietnamese Prisoners of Conscience, Hanoi

Free Press Unlimited, Amsterdam

Front Line Defenders, Dublin

Foundation ADRA Poland, Wroclaw

German-Russian Exchange, Berlin

Gram Bharati Samiti, Jaipur

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly Vanadzor, Yerevan

Helsinki Association of Armenia, Yerevan

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, Warsaw

Human Rights Center Azerbaijan, Baku

Human Rights Center Georgia, Tbilisi

Human Rights Club, Baku

Human Rights Embassy, Chisinau

Human Rights House Foundation, Oslo

Human Rights Information Center, Kyiv

Human Rights Matter, Berlin

Human Rights Monitoring Institute, Vilnius

Human Rights Now, Tokyo

Human Rights Without Frontiers International, Brussels

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, Budapest

IDP Women Association “Consent”, Tbilisi

IMPARSIAL, the Indonesian Human Rights Monitor, Jakarta

Index on Censorship, London

Indonesian Legal Roundtable, Jakarta

Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, Jakarta

Institute for Democracy and Mediation, Tirana

Institute for Development of Freedom of Information, Tbilisi

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

International Partnership for Human Rights, Brussels

International Service for Human Rights, Geneva

International Youth Human Rights Movement

Jerusalem Institute of Justice, Jerusalem

Jordan Transparency Center, Amman

Justiça Global, Rio de Janeiro

Justice and Peace Netherlands, The Hague

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law, Almaty

Kharkiv Regional Foundation Public Alternative, Kharkiv

Kosovo Center for Transparency, Accountability and Anti-Corruption – KUND 16, Prishtina

Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims, Prishtina

Lawyers for Lawyers, Amsterdam

Lawyers for Liberty, Kuala Lumpur

League of Human Rights, Brno

Macedonian Helsinki Committee, Skopje

Masyarakat Pemantau Peradilan Indonesia (Mappi FH-UI), Depok

Moscow Helsinki Group, Moscow

National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders, Kampala

Netherlands Helsinki Committee, The Hague

Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (SIM), Utrecht University, Utrecht

NGO “Aru ana”, Aktobe

Norwegian Helsinki Committee, Oslo

Pakistan Rural Workers Social Welfare Organization (PRWSWO), Bahawalpur

Pensamiento y Acción Social (PAS), Bogotá

Pen International, London

People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD), Seoul

Philippine Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA), Manila

Promo-LEX Association, Chisinau

Protection International, Brussels

Protection Desk Colombia, alianza (OPI-PAS), Bogotá

Protection of Rights Without Borders, Yerevan

Public Association Dignity, Astana

Public Association “Our Right”, Kokshetau

Public Fund “Ar.Ruh.Hak”, Almaty

Public Fund “Ulagatty Zhanaya”, Almaty

Public Verdict Foundation, Moscow

Regional Center for Strategic Studies, Baku/ Tbilisi

Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), Lagos

Stefan Batory Foundation, Warsaw

Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Petaling Jaya

Swiss Helsinki Association, Lenzburg

Transparency International Anti-corruption Center, Yerevan

Transparency International Austrian chapter, Vienna

Transparency International Česká republika, Prague

Transparency International Deutschland, Berlin

Transparency International EU Office, Brussels

Transparency International France, Paris

Transparency International Greece, Athens

Transparency International Greenland, Nuuk

Transparency International Hungary, Budapest

Transparency International Ireland, Dublin

Transparency International Italia, Milan

Transparency International Moldova, Chisinau

Transparency International Nederland, Amsterdam

Transparency International Norway, Oslo

Transparency International Portugal, Lisbon

Transparency International Romania, Bucharest

Transparency International Secretariat, Berlin

Transparency International Slovenia, Ljubljana

Transparency International España, Madrid

Transparency International Sweden, Stockholm

Transparency International Switzerland, Bern

Transparency International UK, London

UNITED for Intercultural Action the European network against nationalism, racism, fascism and in support of migrants, refugees and minorities, Budapest

United Nations Convention against Corruption Civil Society Coalition

Villa Decius Association, Krakow

Vietnam’s Defend the Defenders, Hanoi

Vietnamese Women for Human Rights, Saigon

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, Harare[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1504604895654-8e1a8132-5a81-8″ taxonomies=”8883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Jun 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned, journalists’ and freedom of expression organisations, are writing to urge the Permanent Council of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe to appoint a new mandate holder to the Office of OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media (RFoM) following the end of Ms Dunja Mijatović’s tenure in the position in March of this year.

As we stated in our letter dated 16 February 2017, we believe strongly in the high value and importance of the Office of the RFoM, and in the mandate of the Representative that has been agreed by all OSCE participating states:

“The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media has an early warning function and provides rapid response to serious non-compliance with regard to free media and freedom of expression. The OSCE participating States consider freedom of expression a fundamental and internationally recognised human right and a basic component of a democratic society. Free media is essential to a free and open society and accountable governments. The Representative is mandated to observe media developments in the participating States and to advocate and promote full compliance with the Organisation’s principles and commitments in respect of freedom of expression and free media.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The work of the RFoM remains of critical importance, with journalists and media workers facing significant and new pressures across the OSCE region

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Since its inception in 1998, the Office has had a mandate holder without interruption, and successive Representatives on Freedom of the Media have helped to maintain freedom of media on the policy agenda within the OSCE and made a considerable contribution to a number of initiatives related to press freedom in the OSCE region. This was made possible by both the independence conferred on the Office and the profile of the Representatives who have shown determination, vision and steadfastness in fulfilling their mandate.

The former mandate holder, Ms Dunja Mijatović, left the Office on 10 March 2017, having served a one-year extension of her two three-year terms. The Austrian Chairmanship of the OSCE gave a deadline of 7 April 2017 for nominations for her replacement and yet, to date, there has been no announcement of her successor.

This situation is of great concern to media and other stakeholders, including many organisations actively concerned for media freedom in Europe who fear losing a valuable partner and voice. The work of the RFoM remains of critical importance, with journalists and media workers facing significant and new pressures across the OSCE region.

While the Office of the Representative has continued to uphold its mandate in the transition period since Ms Mijatović’s departure, the strong leadership of the Representative is essential to ensure national governments across the region remain accountable to their commitments to the protection of journalists and media independence. A failure to appoint a new mandate holder risks rolling back progress achieved in protecting media freedoms, undermining advances into promoting stable, tolerant and accountable societies.

That is why we urge all Participating States to press on the OSCE the need to appoint a new Representative on Freedom of the Media without delay and to ensure the Office’s achievements over the last two decades are not lost.

We also encourage the Participating States to use their collective weight to influence the choice of the new Representative, and by doing so, ensure the best profile possible with a track record of independence and proved commitment to freedom of expression and freedom of the press for this important position.

19 June 2017

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Article 19

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute (IPI)

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1497967874947-321034c0-bb1f-2″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91122″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/05/stand-up-for-satire/”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Mar 2017 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

JOINT ORAL STATEMENT ON THE DETERIORATION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA FREEDOM IN TURKEY

UN Human Rights Council 34th Special Session

Item 4: Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention

15 March 2017

Mr President,

Index on Censorship, PEN International, ARTICLE 19 and 65 organisations are deeply concerned by the continuous deterioration of freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey following the violent and contemptible coup attempt on 15 July 2016.

Over 180 news outlets have been shut down under laws passed by presidential decree following the imposition of a state of emergency. There are now at least 148 writers, journalists and media workers in prison, including Ahmet Şık, Kadri Gürsel, Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, Ayşe Nazlı Ilıcak and İnan Kızılkaya, making Turkey the biggest jailer of journalists in the world. The Turkish authorities are abusing the state of emergency by severely restricting fundamental rights and freedoms, stifling criticism and limiting the diversity of views and opinions available in the public sphere.

Restrictions have reached new heights in the lead up to a crucial referendum on constitutional reforms, which would significantly increase executive powers, set for 16 April 2017. The Turkish authorities’ campaign has been marred by threats, arrests and prosecutions of those who have voiced criticism of the proposed amendments. Several members of the opposition have been arrested on terror charges. Thousands of public employees, including hundreds of academics and opponents to the constitutional reforms, were dismissed in February. Outspoken “No” campaigners have been detained, adding to the overall climate of suspicion and fear. The rights to freedom of expression and information, essential to fair and free elections, are in jeopardy.

In the run-up to the referendum, the need for media pluralism is more important than ever. Voters have the right to be duly informed and to be provided with comprehensive information on all views, including dissenting voices, in sufficient time. The prevailing atmosphere should be one of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. There should be no fear of reprisals.

We urge this Council, its members and observer states, to call on the Turkish authorities to:

- Guarantee equal broadcasting time for all parties and allow for the dissemination of all information to the maximum extent possible in order to ensure that voters are fully informed;

- Put an end to the climate of suspicion and fear by:

- Immediately releasing all those held in prison for exercising their rights to freedom of opinion and expression;

- Ending the prosecutions and detention of journalists simply on the basis of the content of their journalism or alleged affiliations;

- Halting executive interference with independent news organisations including in relation to editorial decisions, dismissals of journalists and editors, pressure and intimidation against critical news outlets and journalists;

- Revoke the excessively broad provisions under the state of emergency, the application of which, in practice, are incompatible with Turkey’s human rights obligations.

Thank you Mr. President

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Albanian Media Institute

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

ARTICLE 19

Association of European Journalists

Basque PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Cartoonists Rights Network International

Center for Independent Journalism – Hungary

Croatian PEN centre

Danish PEN

Digital Rights Foundation

English PEN

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

European Federation of Journalists

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

German PEN

Global Editors Network

Gulf Centre for Human Rights

Human rights watch

Icelandic PEN

Independent Chinese PEN Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Institute for Media and Society

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Media Foundation for West Africa

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Watch

MYMEDIA

Nigeria PEN Centre

Norwegian PEN

Pacific Islands News Association

Pakistan Press Foundation

Palestine PEN

PEN American Center

PEN Austria

PEN Canada

PEN Català

PEN Centre in Bosnia and Herzegovina

PEN Centre of German-Speaking Writers Abroad

PEN Eritrea in exile

PEN Esperanto

PEN Estonia

PEN France

PEN International

PEN Melbourne

PEN Myanmar

PEN Romania

PEN Suisse Romand

PEN Trieste

Portuguese PEN Centre

Punto24

Reporters Without Borders

Russian PEN Centre

San Miguel PEN

Serbian PEN Centre

Social Media Exchange – SMEX

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Wales PEN Cymru

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WANIFRA)

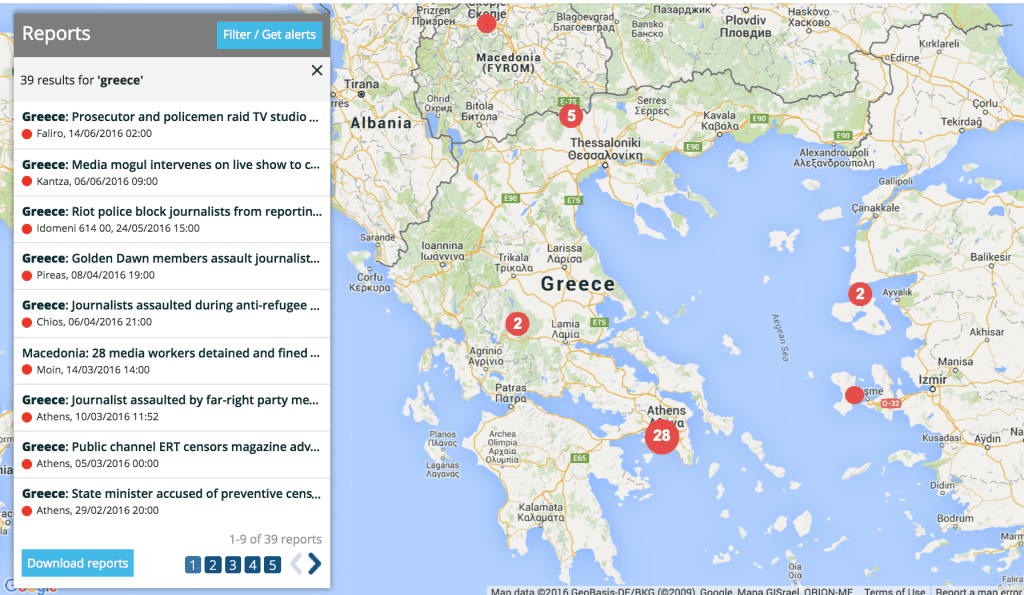

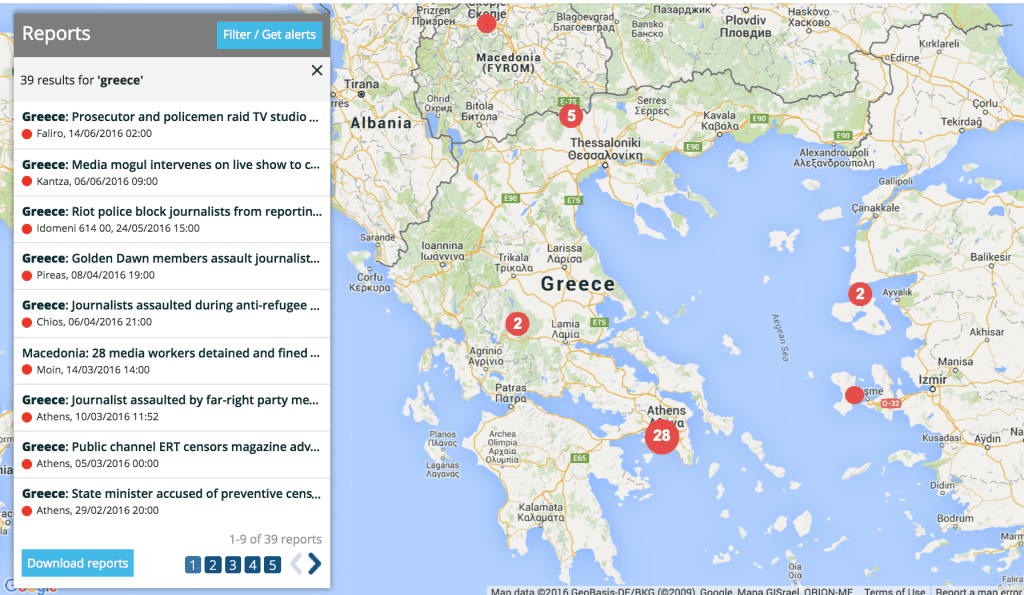

19 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

As Greece tries to deal with around 50,000 stranded refugees on its soil after Austria and the western Balkan countries closed their borders, attention has turned to the living conditions inside the refugee camps. Throughout the crisis, the Greek and international press has faced major difficulties in covering the crisis.

“It’s clear that the government does not want the press to be present when a policeman assaults migrants,” Marios Lolos, press photographer and head of the Union of Press Photographers of Greece said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “When the police are forced to suppress a revolt of the migrants, they don’t want us to be there and take pictures.”

Last summer, Greece had just emerged from a long and painful period of negotiations with its international creditors only to end up with a third bailout programme against the backdrop of closed banks and steep indebtedness. At the same time, hundreds of refugees were arriving every day to the Greek islands such as Chios, Kos and Lesvos. It was around this time that the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, started putting pressure on Greece to build appropriate refugee centres and prevent this massive influx from heading to the more prosperous northern countries.

It took some months, several EU Summits, threats to kick Greece out of the EU free movement zone, the abrupt closure of the internal borders and a controversial agreement between the EU and Turkey to finally stem migrant influx to Greek islands. The Greek authorities are now struggling to act on their commitments to their EU partners and at the same time protect themselves from negative coverage.

Although there were some incidents of press limitations during the first phase of the crisis in the islands, Lolos says that the most egregious curbs on the press occurred while the Greek authorities were evacuating the military area of Idomeni, on the border with Macedonia.

In May 2016, the Greek police launched a major operation to evict more than 8,000 refugees and migrants bottlenecked at a makeshift Idomeni camp since the closure of the borders. The police blocked the press from covering the operation.

“Only the photographer of the state-owned press agency ANA and the TV crew of the public TV channel ERT were allowed to be there,” Lolos said, while the Union’s official statement denounced “the flagrant violation of the freedom and pluralism of press in the name of the safety of photojournalists”.

“The authorities said that they blocked us for our safety but it is clear that this was just an excuse,” Lolos explained.

In early December 2015, during another police operation to remove migrants protesting against the closed borders from railway tracks, two photographers and two reporters were detained and prevented from doing their jobs, even after showing their press IDs, Lolos said.

While the refugees were warmly received by the majority of the Greek people, some anti-refugee sentiment was evident, giving Greece’s neo-nazi, far-right Golden Dawn party an opportunity to mobilise, including against journalists and photographers covering pro- and anti-refugee demonstrations.

On the 8 April 2016, Vice photographer Alexia Tsagari and a TV crew from the Greek channel E TV were attacked by members of Golden Dawn while covering an anti-refugee demonstration in Piraeus. According to press reports, after the anti-refugee group was encouraged by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris to attack anti-fascists, a man dressed in black, who had separated from Golden Dawn’s ranks, slapped and kicked Tsagari in the face.

“Since then I have this fear that I cannot do my work freely,” Tsagari told Index on Censorship, adding that this feeling of insecurity becomes even more intense, considering that the Greek riot police were nearby when the attack happened but did not intervene.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement in late March which stemmed the migrant flows, the Greek government agreed to send migrants, including asylum seekers, back to Turkey, recognising it as “safe third country”. As a result, despite the government’s initial disapproval, most of the first reception facilities have turned into overcrowded closed refugee centres.

“Now we need to focus on the living conditions of asylum seekers and migrants inside the state-owned facilities. However, the access is limited for the press. There is a general restriction of access unless you have a written permission from the ministry,” Lolos said, adding that the daily living conditions in some centres are disgraceful.

Ola Aljari is a journalist and refugee from Syria who fled to Germany and now works for Mapping Media Freedom partners the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. She visited Greece twice to cover refugee stories and confirms that restrictions on journalists are increasing.

“With all the restrictions I feel like the authorities have something to hide,” Aljari told Index on Censorship, also mentioning that some Greek journalists have used bribes in order to get authorisation.

Greek journalist, Nikolas Leontopoulos, working along with a mission of foreign journalists from a major international media outlet to the closed centre of VIAL in Chios experienced recently this “reluctance” from Greek authorities to let the press in.

“Although the ministry for migration had sent an email to the VIAL director granting permission to visit and report inside VIAL, the director at first denied the existence of the email and later on did everything in his power to put obstacles and cancel our access to the hotspot,” Leontopoulos told Index on Censorship, commenting that his behaviour is “indicative” of the authorities’ way of dealing with the press.