6 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features

In France, Bob Dylan is being officially investigated for “incitement to hatred” against Croats for comparing their relationship to Serbs with that between Nazis and Jews in an interview.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information is an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression. Without the ability to access information held by states, individuals cannot make informed democratic choices. Many EU member states have failed to adequately protect freedom of information and the Commission has been criticised for its failure to adequately promote transparency and uphold its commitment to freedom of information.

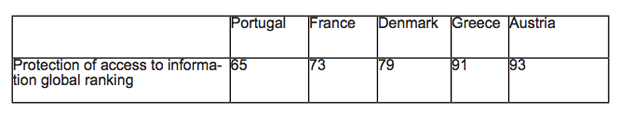

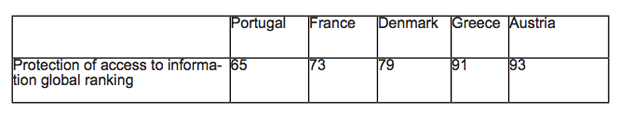

When it comes to assessing global protection for access to information, not one European Union member state ranks in the list of the top 10 countries, while increasingly influential democracies such as India do. Two member states, Cyprus and Spain, are still without any freedom of information laws. Of those that do, many are weak by international standards (see table below).

In many states, the law is not enforced properly. In Italy, public bodies fail to respond to 73% of requests.

The Council of Europe has also developed a Convention on Access to Official Documents, the first internationally binding legal instrument to recognise the right to access the official documents of public authorities. Only seven EU member states have signed up the convention.

Since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, both member states and EU institutions are both bound by freedom of information commitments. Article 42 (the right of access to documents) of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights now recognises the right to freedom of information for EU documents as a fundamental human right Further, specific rights falling within the scope of freedom of information are also enshrined in Article 41 of the Charter (the right to good administration).

As a result, the European Commission has embedded limited access to information in its internal protocols. Yet, while the European Parliament has reaffirmed its commitment to give EU citizens more access to official EU documents, it is still the case that not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. The Danish government used their EU presidency in the first half of 2012 to attempt to forge an agreement between the European Commission, the Parliament and member states to open up public access to EU documents. This attempt failed after a hostile response from the Commission. Attempts by the Cypriot and Irish presidencies to unblock the matter in the Council also failed.

This lack of transparency can and has impacted on public’s knowledge of how decisions that affect human rights have been made. The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has criticised the European Commission for denying access to documents concerning its view of the United Kingdom’s decision to opt out from the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In 2013, Sophie in’t Veld MEP was barred from obtaining diplomatic documents relating to the Commission’s position on the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).

Hate speech

Across the European Union, hate speech laws, and in particular their interpretation, vary with regard to how they impact on the protection for freedom of expression. In some countries, notably Poland and France, hate speech laws do not allow enough protection for free expression. The Council of the European Union has taken action on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by promoting use of the criminal law within nation states in its 2008 Framework Decision. Yet, the Framework Decision failed to adequately protect freedom of expression in particular on controversial historical debate.

Throughout European history, hate speech has been highly problematic, from the experience and ramifications of the Holocaust through to the direct incitement of ethnic violence via the state run media during wars in the former Yugoslavia. However, it is vital that hate speech laws are proportionate in order to protect freedom of expression.

On the whole, the framework for the regulation of hate speech is left to the national laws of EU member states, although all member states must comply with Articles 14 and 17 of the ECHR.[1] A number of EU member states have hate speech laws that fail to protect freedom of expression –- in particular in Poland, Germany, France and Italy.

Article 256 and 257 of the Polish Criminal Code criminalise individuals who intentionally offend religious feelings. The law criminalises public expression that insults a person or a group on account of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or the lack of a religious affiliation. Article 54 of the Polish Constitution protects freedom of speech but Article 13 prohibits any programmes or activities that promote racial or national hatred. Television is restricted by the Broadcasting Act, which states that programmes or other broadcasts must “respect the religious beliefs of the public and respect especially the Christian system of values”. In 2010, two singers, Doda and Adam Darski, where charged with violating the criminal code for their public criticism of Christianity.[2] France prohibits hate speech and insult, which are deemed to be both “public and private”, through its penal code[3] and through its press laws[4]. This criminalises speech that may have caused no significant harm whatsoever to society, which is disproportionate. Singer Bob Dylan faces the possibility of prosecution for hate speech in France. The prosecutor’s office in Paris confirmed that Dylan has been placed under formal investigation by Paris’s Main Court for “public injury” and “incitement to hatred” after he compared the relationship between Croats and Serbs to that of Nazis and Jews.

The inclusion of incitement to hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation into hate speech laws is a fairly recent development. The United Kingdom’s hate speech laws contain specific provisions to protect freedom of expression[5] but these provisions are not absolute. In a landmark case in 2012, three men were convicted after distributing leaflets in Derby depicting a mannequin in a hangman’s noose and calling for the death sentence for homosexuality. The European Court of Human Rights ruled on this issue in its landmark judgment Vejdeland v. Sweden, which upheld the decision reached by the Swedish Supreme Court to convict four individuals for homophobic speech after they distributed homophobic leaflets in the lockers of pupils at a secondary school. The applicants claimed that the Swedish Supreme Court’s decision to convict them constituted an illegitimate interference with their freedom of expression. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 10, noting even if there was, the interference served a legitimate aim, namely “the protection of the reputation and rights of others”.

The widespread criminalisation of genocide denial is a particularly European legal provision. Ten EU member states criminalise either Holocaust denial, or the denial of crimes committed by the Nazi and/or Communist regimes. At EU level, Germany pushed for the criminalisation of Holocaust denial, culminating in its inclusion from the 2008 EU Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. Full implementation of the Framework Decision was blocked by Britain, Sweden and Denmark, who were rightly concerned that the criminalisation of Holocaust denial would impede historical inquiry, artistic expression and public debate.

Beyond the 2008 EU Framework Decision, the EU has taken specific action to deal with hate speech in the Audiovisual Media Service Directive. Article 6 of the Directive states the authorities in each member state “must ensure by appropriate means that audiovisual media services provided by media service providers under their jurisdiction do not contain any incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality”.

Hate speech legislation, particularly at European Union level, and the way this legislation is interpreted, must take into account freedom of expression in order to avoid disproportionate criminalisation of unpopular or offensive viewpoints or impede the study and debate of matters of historical importance.

[1] ‘Article 14 – discrimination’ contains a prohibition of discrimination; ‘Article 17 – abuse of rights’ outlines that the rights guaranteed by the Convention cannot be used to abolish or limit rights guaranteed by the Convention.

[2] The police charged vocalist and guitarist Adam Darski of Polish death metal band Behemoth with violating the Criminal Code for a performance in 2007 in Gdynia during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet” and tore up a copy of the Bible; singer Doda, whose real name is Dorota Rabczewska, was charged with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”.

[3] Article R625-7

[4] Article 24, Law on Press Freedom of 29 July 1881

[5] The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A[12] to criminalising attempting to “stir up religious hatred.” A further provision to protect freedom of expression (Section 29J) was added: “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system.”

2 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

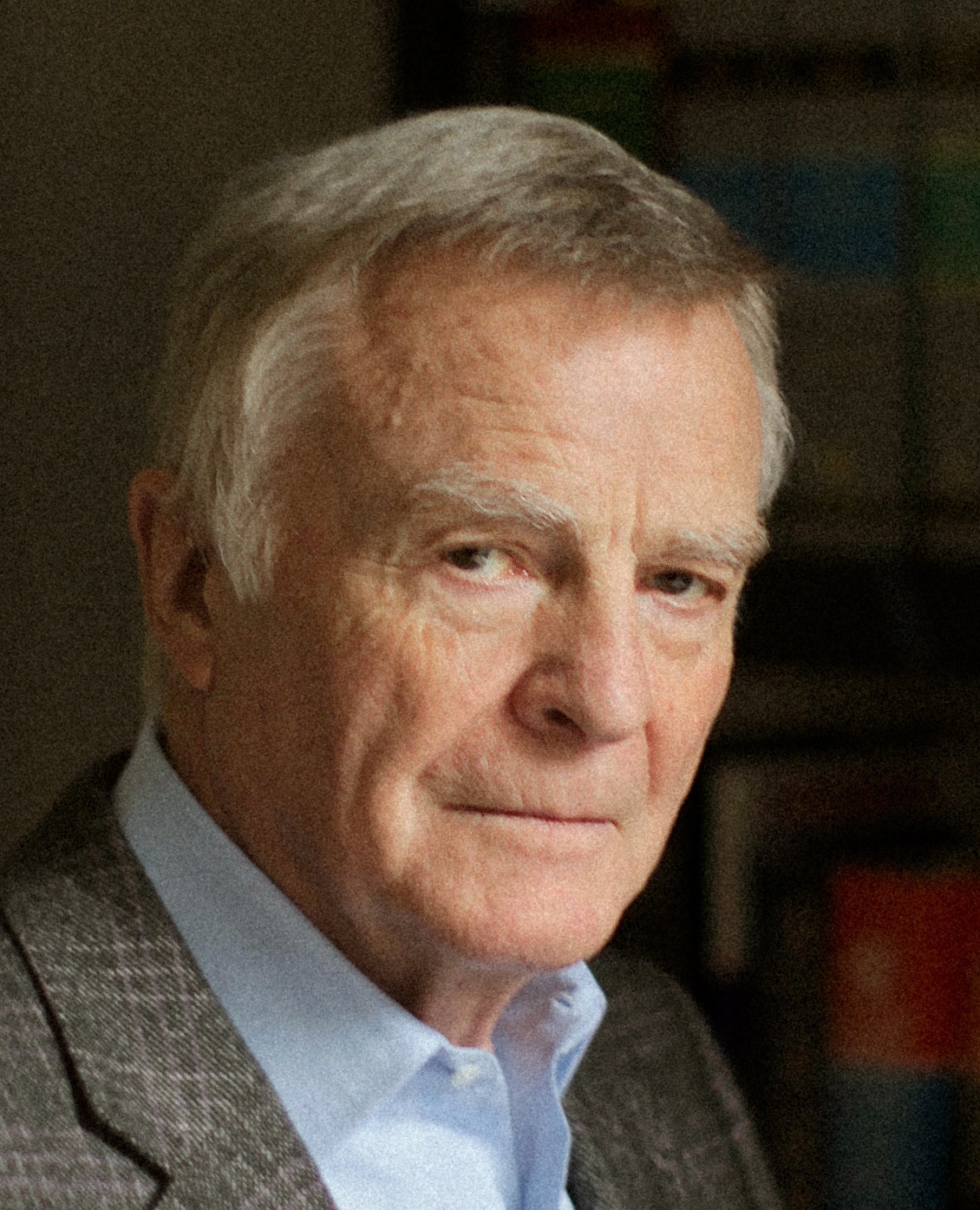

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).

12 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom Reports, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society

As Ukraine experiences ongoing protests over lack of European integration, Index’ new report looks at the EU’s relationship with freedom of expression (Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

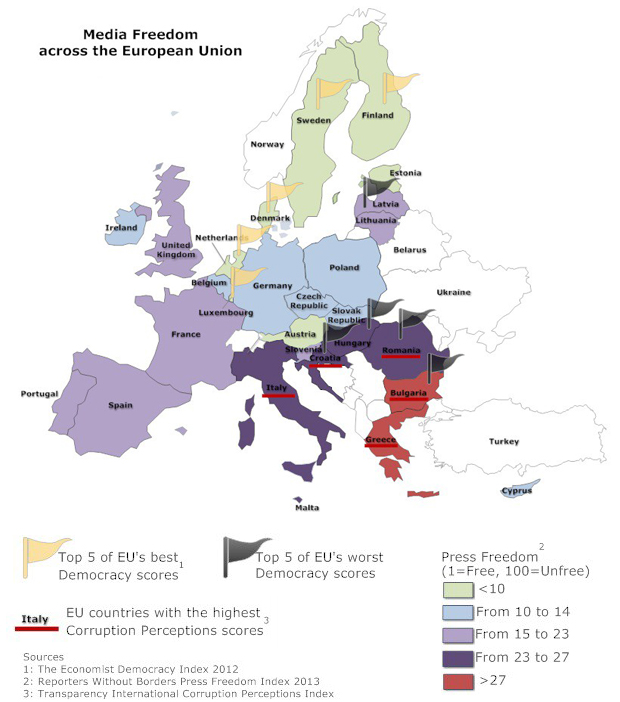

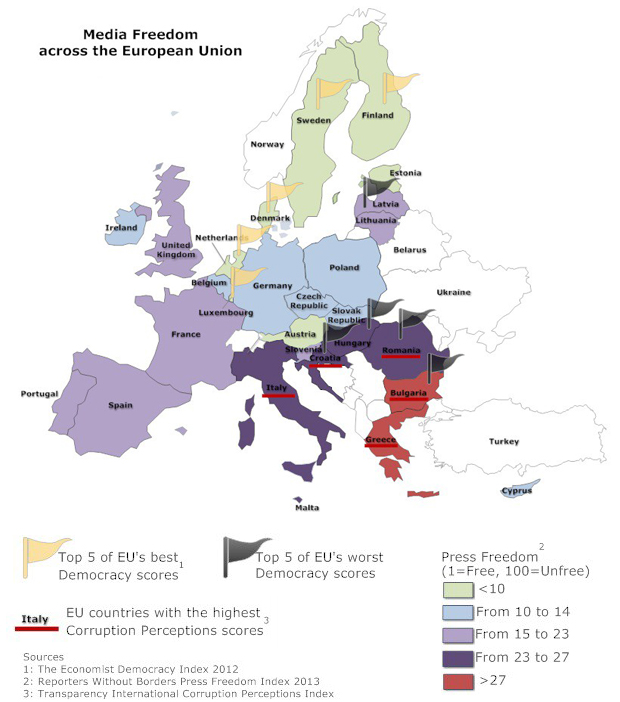

Index on Censorship’s policy paper, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression, looks at freedom of expression both within the European Union’s 28 member states, which with over 500 million people account for about a quarter of total global economic output, but also how this union defends freedom of expression in the wider world. States that are members of the European Union are supposed to share “European values”, which include a commitment to freedom of expression. However, the way these common values are put into practice vary: some of the world’s best places for free expression are within the European Union – Finland, Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden – while other countries such as Italy, Hungary, Greece and Romania lag behind new and emerging global democracies.

This paper explores freedom of expression, both at the EU level on how the Commission and institutions of the EU protect this important right, but also across the member states. Firstly, the paper will explore where the EU and its member states protect freedom of expression internally and where more needs to be done. The second section will look at how the EU projects and defends freedom of expression to partner countries and institutions. The paper will explore the institutions and instruments used by the EU and its member states to protect this fundamental right and how they have developed in recent years, as well as the impact of these institutions and instruments.

Outwardly, a commitment to freedom of expression is one of the principle characteristics of the European Union. Every European Union member state has ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR); the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and has committed to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To complement this, the Treaty of Lisbon has made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding which means that the EU institutions and member states (if they act within the scope of the EU law) must act in compliance with the rights and principles of the Charter. The EU has also said it will accede to the ECHR. Yet, even with these commitments and this powerful framework for defending freedom of expression, has the EU in practice upheld freedom of expression evenly across the European Union and outside with third parties, and is it doing enough to protect this universal right?

Within the European Commission, there has been considerable analysis about what should be done when member states fail to abide by “European values”, Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these perceived values and the rights that accompany them. With threats to freedom of expression increasing, it is essential that this is taken up by the Commission sooner rather than later.

To date, most EU member states have failed to repeal criminal sanctions for defamation, with only Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland and the UK having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, since then little action has been taken by EU member states. There also remain significant issues in the field of privacy law and freedom of information across the EU.

While the European Commission has in the past tended to view its competencies in the field of media regulation as limited, due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at a possible enhancement of its role in this area.

With media plurality limited across Europe and in fact potentially threatened by the convergence of media across media both online and off (and the internet being the most concentrated media market), the Commission must take an early view on whether it wishes to intervene more fully in this field to uphold the values the EU has outlined. Political threats against media workers are too commonplace and risks to whistleblowers have increased as demonstrated by the lack of support given by EU member states to whistleblower Edward Snowden. That the EU and its member states have so clearly failed one of the most significant whistleblowers of our era is indicative of the scale of the challenge to freedom of expression within the European Union.

The EU and its member states have made a number of positive commitments to protect online freedom, including the EU’s positioning at WCIT, the freedom of expression guidelines and the No-Disconnect strategy helping the EU to strengthen its external polices around promoting digital freedom. These commitments have challenged top-down internet governance models, supported the multistakeholder approach, protected human rights defenders who use the internet and social media in their work, limited takedown requests, filters and others forms of censorship. But for the EU to have a strong and coherent impact at the global level, it now needs to develop a clear and comprehensive digital freedom strategy. For too long, the EU has been slow to prioritise digital rights, placing the emphasis on digital competitiveness instead. It has also been the case that positive external initiatives have been undermined by contradictory internal policies, or a contradiction of fundamental values, at the EU and member state level. The revelations made by Edward Snowden show that EU member states are violating universal human rights through mass surveillance.

The Union must ensure that member states are called upon to address their adherence to fundamental principles at the next European Council meeting. The European Council should also address concerns that external government surveillance efforts like the US National Security Agency’s Prism programme are undermining EU citizens’ rights to privacy and free expression. A comprehensive overarching digital freedom strategy would help ensure coherent EU policies and priorities on freedom of expression and further strengthen the EU’s influence on crucial debates around global internet governance and digital freedom. With the next two years of ITU negotiations crucial, it’s important the EU takes this strategy forward urgently.

While the European Commission has in the past tended to view its competencies in the field of media regulation as limited, due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at a possible enhancement of its role in this area.

With media plurality limited across Europe and in fact potentially threatened by the convergence of media across media both online and off (and the internet being the most concentrated media market), the Commission must take an early view on whether it wishes to intervene more fully in this field to uphold the values the EU has outlined.

Political threats against media workers are too commonplace and risks to whistleblowers have increased as demonstrated by the lack of support given by EU member states to whistleblower Edward Snowden. That the EU and its member states have so clearly failed one of the most significant whistleblowers of our era is indicative of the scale of the challenge to freedom of expression within the European Union.

Where the EU acts with a common approach among the member states, it has significant leverage to help promote and defend freedom of expression globally. To develop a more common approach, since the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has enhanced its set of policies, instruments and institutions to promote human rights externally, with new resources to do so. Enlargement has proved the most effective tool to promote freedom of expression with, on the whole, significant improvements in the adherence to the principles of freedom of expression in countries that have joined the EU or where enlargement is a real prospect. That this respect for human rights is a condition of accession to the EU shows that conditionality can be effective. Whereas the eastern neighbourhood has benefitted from the real prospect of accession (for some countries), in its southern neighbourhood, the EU has failed to promote freedom of expression by placing security interests first and also by failing to react quickly enough to the transitions in its southern neighbourhood following the events of the Arab Spring. The new strategy for this region is welcome and may better protect freedom of expression, but with Egypt in crisis, the EU may have acted too late. The EU must assess the effectiveness of some of its foreign policy instruments, in particular the dialogues for particular countries such as China.

The freedom of expression guidelines provide an excellent opportunity to reassess the criteria for how the EU engages with third party countries. Strong freedom of expression guidelines will allow the EU to better benchmark the effectiveness of its human rights dialogues. The guidelines will also reemphasise the importance of the EU, ensuring that the right to freedom of expression is protected within the EU and its member states. Otherwise, the ability of the EU to influence external partners will be limited.

Headline recommendations

• After recent revelations about mass state surveillance the EU must develop a roadmap that puts in place strong safeguards to ensure narrow targeted surveillance with oversight not mass population surveillance and must also recommit to protect whistle-blowers

• The European Commission needs to put in place controls so that EU directives cannot be used for the retention of data that makes mass population surveillance feasible

• The EU has expanded its powers to deal with human rights violations, but is reluctant to use these powers even during a crisis within a member state. The EU must establish clear red lines where it will act collectively to protect freedom of expression in a member state

• Defamation should be decriminalised across the EU

• The EU must not act to encourage the statutory regulation of the print media but instead promote tough independent regulation

• Politicians from across the EU must stop directly interfering in the workings of the independent media

• The EU suffers from a serious credibility gap in its near neighbourhood – the realpolitik of the past that neglected human rights must be replaced with a coherent, unified Union position on how to promote human rights

Recommendations

- The EU has expanded its powers to deal with human rights violations, but is reluctant to use these powers even during a crisis within a member state. The EU must establish clear red lines where it will act collectively to protect freedom of expression in a member state

- The EU should cut funding for member states that cross the red lines and breach their human rights commitments

Libel, privacy and insult

- Defamation should be decriminalised in line with the recommendations of the Council of Europe parliamentary assembly, and the UN and OSCE’s special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.

- Insult laws that criminalise insult to national symbols should be repealed

Freedom of information

- To better protect freedom of information, all EU member states should sign up to the Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents

- Not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. More must be done by the Commission to protect freedom of information

Media freedom & plurality

- The EU must revisit its competencies in the area of media regulation in order to prevent the most egregious breaches of the right to freedom of expression in particular the situations that arose in Italy and Hungary

- The EU must argue against statutory regulation of the print media and argue for independent self-regulation where media bandwidth is no longer limited by spectrum and other considerations

- Member states must not allow political interference or considerations of “political balance” into the workings of the media, where this happens the EU should be considered competent to act to protect media freedom and pluralism at a state level

- The EU is not doing enough to protect whistleblowers. National states must do more to protect journalists from threats of violence and intimidation

Digital

- The Commission must prepare a roadmap for collective action against mass state surveillance

- The EU is right to argue against top-down state control over internet governance it must find more natural allies for this position globally

- The Commission should proceed with a Directive that sets out the criteria takedown requests must meet and outline a process that protects anonymous whistle-blowers and intermediaries from vexatious claims

The EU and freedom of expression in the world

- The EU suffers from a credibility issue in its southern neighbourhood. To repair its standing in the wider world, the EU and its member states must not downgrade the importance of human rights in any bilateral or multilateral relationship

- The EU’s EEAS Freedom of Expression guidelines are welcome. To be effective, they need to focus on the right to freedom of expression for ordinary citizens and not just media actors

- The guidelines need to become the focus for negotiations with external countries, rather than the under-achieving human rights dialogues

- With criticism of the effectiveness of the human rights dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states

The European Union contains some of the world’s strongest defenders of freedom of expression, but also a significant number of member states who fail to meet their European and international commitments. To deal with this, in recent years, the European Union’s member states have made new commitments to better protect freedom of expression. The new competency of the European Court of Justice to uphold the values enshrined in the European Convention of Human Rights will provide a welcome alternative forum to the increasingly deluged European Court of Human Rights. This could have significant implications for freedom of expression within the EU. Internally within the EU there is still much that could be done to improve freedom of expression. It is welcome that that the EU and its member states have made a number of positive commitments to protect online freedom, with new action on vexatious takedown notices and coordinated action to protect the multistakeholder model of internet governance. Increasing Commission concern over media plurality may also be positive in the future.

Yet there are a number of areas where the EU must do more. The decriminalisation of defamation across Europe should be a focal point for European action in line with the Council of Europe’s recommendations. National insult laws should be repealed. The Commission should not intervene to increase its powers over national media regulators, but should act where it has clear competencies, in particular to prevent media monopolies and to help deal with conflict of interests between politicians and state broadcasters. Most importantly, discussions of mass population surveillance at the European Council in October must be followed by a roadmap outlining how the EU will collectively take action on this issue. Without internal reform to strengthen protections for freedom of expression, the EU will not enjoy the leverage it should to promote freedom of expression externally to partner countries. While the External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines are welcome, they must be impressed upon member countries as a benchmark for reform.

Externally, the EU has failed to deliver on the significant leverage it could have as the world’s largest trading block. Where the EU has acted in concert, with clear aims and objectives for partner countries, such as during the process of enlargement, it has had a big impact on improving and protecting freedom of expression. Elsewhere, the EU has fallen short, particularly in its southern neighbourhood and in its relationship with China, where the EU has continued human rights dialogues that have failed to be effective.

New commitments and new instruments post-Lisbon may better protect freedom of expression in the EU and externally. Yet, as the Snowden revelations show, the EU and its member states must do significantly more to deliver upon the commitments that have been agreed.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Apr 2013 | Europe and Central Asia

This article was originally published on opendemocracy.net

Kostas Vaxevanis gives his speech after winning Index on Censorship’s 2013 Journalism Award

(more…)