28 Jan 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Galileo is “vehemently suspect by this Holy office of heresy, that is, of having believed and held the doctrine (which is false and contrary to the Holy and Divine Scriptures) that the sun is the centre of the world, and that it does not move from east to west, and that the earth does move, and is not the centre of the world…”

Sentencing at the Inquisition of Galileo,

22 June 1633

Every philosopher, prophet, scientist and great political and social reformer of their day has started as a heretic. Mohammad blasphemed against the polytheist social order of Mecca, Jesus against the monotheistic legalese of the Temple, and Moses before them against the idols of the Children of Israel. The right to heresy, to blasphemy, and to speak against prevalent dogma is as sacred and divine as any act of prayer. If our hard earned liberty, our desire to be irreverent of the old and to question the new, can be reduced to one, basic and indispensable right: it must be the right to free speech. Our freedom to speak represents our freedom to think, our freedom to think our ability to create, innovate and progress. You cannot kill an idea, but you can certainly kill a person for expressing it. For if liberty means anything at all, it is the right to express oneself without being killed for it.

The importance of internalised liberalism in contemporary British society has come to represent a cornerstone of modern Liberal Democrat thinking.1 This paper aims to extend that notion by arguing that liberalism is an idea that should be actively, universally and externally asserted, among, between and across communities, cultures and borders. A certain neoorientalism has crept upon us, partly in reaction to the failed militarism of the neo-conservative years, but mainly attributable to historical self-critical attitudes towards the British Empire. This neo-orientalism interprets liberalism as a Western construct ill-fitting to non-Western cultures. Struggling, dissenting liberals within minority community contexts find that they have no greater enemy than these neo-orientalists who lend credence to the idea that they are somehow an inauthentic expression of their ‘native’ culture. This view, while embracing moral relativity, reduces other cultures to lazy, romanticised and static cliches. Far worse, it ends up not just tolerating but actively promoting illiberal practices in the name of assumed cultural authenticity, even where such promoted practices are in fact ahistoric, inauthentic neo-fundamentalisms.

There is a great betrayal of minorities-withinminorities afoot. The price of this betrayal in modern Britain is monocultural ghettos that stifle minority opportunities by acquiescing to the silencing of innovative voices, in the name of this assumed cultural authenticity. Only by the universal reassertion of free speech will those silent voices stand any chance of being heard. Free speech is not a ‘Western’ ideal but a human one.

Globalisation and identity

Rapid globalisation has helped to erode national identity. Encouraged by innovations in international travel and communications, we have witnessed instead the rise of lateral transnational identities that reach across borders, rather than within them, to find affinity. Consequently, previously isolated pockets of parochialisms are connecting, providing a sense of belonging to global causes beyond geographical boundaries.

A common fear is that living in multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies leads to the disintegration of one’s own culture. Some, especially those from minority communities, feel the need to protect themselves against this threat by ardently clinging on to, and exaggerating, a narrow form of their ethnic or religious identity. ‘Cultural differences’ are therefore emphasised and ring-fenced more than they otherwise would be.

Of course it is possible to do this in a healthy way, and many do. But some modern cultural insecurities have warped to form a broad anti-establishment sentiment in Britain. Victimhood is used as means to create a sense of besiegement, leading to highly exclusionary identity formations. The rise of identity politics and reactionary political or religious ideological trends across Europe can be said to be inspired

by this fear of losing one’s identity, and sense of belonging, via globalisation.

It is usually the case that those who are most passionately against the status quo are the most active at proselytising, and so it has come to pass that it is the political extremes – Far Right, Anarchist and Islamist – who have best exploited this ability to build exclusionary, transnational identities. Here, globalisation can be said to have ‘sharpened the differences and increased cultural confrontations’2 in Europe rather than creating integrated, multicultural melting pots.

Cultural relativity

In response to tension created by the rise in reactionary political trends, liberal society has understandably been inclined to reduce the risk of conflict. Words, images and actions that could be deemed offensive by certain sections of a community, especially a religious community, are subsequently avoided by us in apprehension, worried such actions may create an unwanted reaction. In essence, unhealthy taboos that ideally need to be broken are simply further entrenched. In some cases these taboos are actively and tragically enforced in the guise of defending diversity.

In what would now be considered a preposterous – and thankfully illegal – measure, in 1993 the London Borough of Brent proposed a motion to make Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) legal. The motion called for FGM to be classed as a “right specifically for African families who want to carry on their tradition whilst living in this country”. Ann John, a local Brent councillor at the time, successfully opposed this motion and tabled her own amendment in which she called FGM “barbaric” and said it was “no more a valid cultural tradition than is cannibalism”. But this was the 1990s, the decade of unhinged state-sponsored monocultural ghettoisation, unfortunately named multiculturalism. Subsequently, for her heresy Ann suffered a tirade of abuse and threats. She was called a “colonialist missionary” who “thinks she knows what is best for Africans” and even threatened with mutilation herself. It took until 2014 for Brent Council to finally teach FGM prevention in all its schools. Yet according to statistics cited by the government’s Department for International Development (DfID), over 20,000 girls under the age of 15 are still at risk of FGM in the UK every year.3

At the time of writing, Britain is yet to witness one successful conviction for this reprehensible practice. Ann John has an explanation for this, interviewed in 2014 she “believes her treatment scared off other people from speaking out against FGM for years out of a fear of being called racist”.4

As with homophobia, the cultural war against FGM is slowly being won in Britain. But the fact that many still feel unable to make negative judgements about other practices found in alternative cultures, and our own, is deeply problematic. We liberals will be rightly judged by the extent of our concern for the weakest among us. In today’s Britain, the weakest among us are often assumed to be minority communities. In fact, the weakest are those minorities-within-minorities for whom the legal right to exit from their communities’ constraints amounts to nothing before the enforcement of cultural and religious shaming. Those most vulnerable would include dissenting religious sects, feminists, LGBT and apostates, all of whom may question the prevailing dogma within their group identity. Liberalism in this instance is duty bound to unhesitatingly support the dissenting individual over the group, the heretic over the orthodox, innovation over stagnation and free speech over offence. Or, as John Maynard Keynes would say, to “appear unorthodox, troublesome, dangerous, disobedient to them that begat us”.5

Instead, what is often the case is that prevailing neo-orientalist thinking would either remain silent, or criticise those who do seek to challenge dogma, for ‘causing offence’. An assumption is made here about what ‘authenticity’ in a given culture is. Subsequent actions and advice, policy or otherwise, are patronisingly given on the basis of this assumption.

Confirmation bias leads to seeking reaffirmation for this assumption from the very ‘community leaders’ who stand most to gain by reaffirming it. Few stop to ask why it is assumed that Britain’s three million Muslims, the vast majority of whom are not religious, would wish to engage the public through Citizen Khan6 like conservative figures.7

Not only is this assumption lazy, but it suggests that each culture is effectively a homogenous, static group; the members of which think the same way and would all be equally offended by the same thing, none of whom can speak as individuals, but like native savages would require ‘chiefs’ to speak on their collective behalf. If seeking unity in politics is fascism, then seeking unity in religion is theocracy. Liberalism cherishes internal diversity in both.

When such cultural relativity becomes the norm, more progressive and liberal elements within minority religious communities or cultural groups in particular are betrayed, only then to be besieged by all sides. Through this reductionist quest for cultural ‘authenticity’, anything deemed Western is incrementally excluded by our neo-orientalists as inauthentic, until only the most conservative, dogmatic and regressive voices remain – which are, ironically, entirely a product of modernity in themselves.

Alas, this search for authenticity is a battle that only fundamentalists and fascists can win. Bigotry is not merely generalising a culture, religion or race for hate. Those who generalise a culture, religion or race in order to display a patronising love, more befitting to a pet, must also be considered bigots. And only the most regressive forces stand to gain by exaggerating their culture, religion or race, either in defiance or compliance to bigots. Liberalism must seek out the individual, not the stereotype. Because such reductionist approaches are nothing but an outdated superiority complex that should have died along with the Empire.8 Because to deem the ‘poor natives’ as being too primitive to grasp liberalism, and to subsequently hold them to and judge them by a lower standard, is a poverty of expectation.

Let us take the example of the Law Society of England and Wales. In early 2014, the Law Society, a necessarily secular institution, published a practice note advising solicitors on how to draft wills in accordance with “Sharia Law”; except there is no single version of Sharia, and in Arabic, Sharia is a noun, not an adjective to describe the noun ‘law’. These guidelines included assertions that “Sharia Law” endorses the disinheritance of apostates and adopted children, and discriminates against women. It is true that English Common Law allows for inheritance to be decided in any way that pleases the testator. The concern here however is why the Law Society felt entitled not only to intervene in an intra-religious debate about the nature and applicability of Islam today, but that when doing so it picked the most regressive form of medievalism and promoted it as ‘authentic’ Islam,9 thus betraying, and further isolating, liberal reforming Muslims from the outset.10

The publication of cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten are a case in point. It was only when the press started approaching certain ‘community leaders’ that an angry response became apparent, especially since only religious imams were approached.11

Likewise, I recently tweeted an innocuous stick figure, not drawn by me, of an image called ‘Mo’ saying “Hi” to an image called ‘Jesus’. The image called ‘Jesus’ said in reply, “How ya doin?”. I did so because, as a Muslim, I felt it was necessary to make the point that I was not offended by a benign cartoon in light of media portrayals of all Muslims as overly-sensitive. I did so in the aftermath of a live TV debate on the subject. Ironically, and while I vehemently disagree with the veil, my intervention came in the context of attempting to defend the rights of a veiled Muslim woman who had just been told that her veil ‘offends’ people. After asserting her own right to wear what she likes, this lady retorted to a man next to her that he however could not wear his tee-shirt with the above described stick figure labelled ‘Mo’, because it offends her. My reply was that people are free to take offence at how I dress, but they are not free to insist that I dress in a way that does not offend them. This principle applies to all, fairly. I then retweeted that I was not offended by this stick figure labelled ‘Mo’. Blasphemy is in the eye of the beholder. I was subsequently inundated with a torrent of abuse and violent threats by some vocal but reactionary Muslims. More telling was the chastisement by many non-Muslim neo-orientalists who accused me of being insensitive to ‘Muslim feelings’, as if I myself was not one of these Muslims with some ‘feelings’ I needed to express.

And then came the attacks on Charlie Hebdo in Paris.

Taking the easy route by condemning the radical for causing unnecessary trouble is overwhelmingly tempting, and incredibly lazy. Liberals would instinctively see the birth pangs of progress through such heresy. Cultural relativism has created an absurd situation whereby minorities-within-minorities are no longer free to move intra-cultural debates forward. I recall once as a child that a passerby approached a gay couple on the street and told them not to hold hands in public, asking the gay couple “are you deliberately trying to offend us?” I rest my case.

The inconvenient minority

And so that great lynchpin of liberty, freedom of speech, as defined by Article 19 of the UDHR,12 is being eroded by exclusionary group identities. These groups struggle to compete over who is more offended, and who is more entitled. Civil society is now expected to self-censor and the term ‘tolerance’, as explained by Flemming Rose, is ‘no longer about the ability to tolerate things for which we do not care, but more about the ability to keep quiet and refrain from saying things that others may not care to hear’.13

This brings me to the term ‘Islamophobia’, often deployed – even against other Muslims – as a shield against any criticism, and as a muzzle on free speech. If heresy is to be celebrated, it follows that no idea, no matter how ‘deeply held’, is given special status. For there will always be an equally ‘deeply held’ belief in opposition to it. Hatred motivated specifically to target Muslims, people like me, must be condemned.

But to confuse this hatred with satirising, questioning, researching, reforming, contextualising or historicising Islam, or any other faith or dogma, is as good as returning to Galileo’s Inquisition. It follows, therefore, that any liberal naturally concerned with a fair society must be the first to openly defend against the erosion of free speech, especially when deceptively done in the name of minority rights.

Amidst a wave of self-doubt, blasphemy laws, though formally abolished in the UK, are effectively being revived by a cultural climate that purports to be liberal yet upholds illiberalism. Ultimately, restrictions on freedom of speech achieve only one thing – the domination of regressive ideals. Reactionaries are the first to take offence, and the first to demand punitive action against those who they deem offensive. In this way we actively empower illiberal dogma in the name of ‘diversity’, while abandoning vulnerable activists within minorities in the name of ‘respect for difference’.

Neo-orientalist reticence is in part driven by genuine concern of a racist backlash against minority communities by right wing bigots. Britain has become a place where white racists and Christian fundamentalists ally to the Right on domestic issues, while Islamists and Muslim fundamentalists ally to the Left on foreign policy issues. Both groups are able to co-opt the political rhetoric of each political wing to fuel their narrative of victimhood. Both are able to intimidate the ‘other’. Though this fear of racism is genuine – I have personally had to endure being violently targeted by racists over a prolonged period – ignoring Islamist extremism in the name of respect for difference will only fuel racism more by

feeding the Far Right’s victimhood narrative. Both extremes are in perfect symbiosis, feeding off each other to justify their respective grievances. But the difference between fairness and tribalism is the difference between choosing principles and choosing sides. Only a liberal torch can consistently shine through the fog of Far Right and Islamist extremisms and assert itself with any level of consistency.

George Orwell said, “The point is that the relative freedom which we enjoy depends on public opinion. The law is no protection. Governments make laws, but whether they are carried out, and how the police behave, depends on the general temper in the country. If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it; if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them…” To Orwell’s admirable concern for inconvenient minorities, I would only add one idea: the cost of betraying people’s right to heresy is that inconvenient minorities-withinminorities are, in fact, the very first to be persecuted.

Maajid Nawaz is author of his autobiographical story Radical, Chairman of the counter-extremism organisation Quilliam, and a Liberal Democrat Parliamentary candidate for London’s Hampstead and Kilburn. The author would like to thank Hannah Larn and Ghaffar Hussain for their help. Maajid Nawaz can be contacted on Twitter @MaajidNawaz. The opinions expressed in this guest post are the author’s own.

This article was originally published in Centre Forum. It is reposted here with the author’s permission.

Footnotes:

1. David Laws and Paul Marshall (eds), ‘The Orange Book: Reclaiming Liberalism’, London, 2004

2. Erika Harris, Nationalism: Theories and Cases, Edinburgh, 2009

3. Improving the Lives of Girls and Women in the World’s Poorest Countries, DfID

4. Evening Standard, ‘Ann John: I was branded a colonialist for fighting against ‘barbaric’ FGM’, Anna Davis, 28 March 2014.

5. John Maynard Keyes, ‘Am I a Liberal?’, Liberal Summer School, August 1 1925

6. Citizen Khan, BBC One sitcom, written and played by Adil Ray

7. See Amartya Sen: ‘Identity and Violence’ Allen Lane, London 2006

8. For further reading see Edward W. Said, ‘Orientalism’, 1978

9. See the Law Society, Sharia succession rules, 13th March 2014 and a response by the Lawyers Secular Society (LSS) ‘The Law Society should stay out of the theology business’

10. Only after some laudable campaigning, not least from the Lawyer’s Secular Society and One Law for All, among others, did the Law Society eventually – and quietly – drop this practice note.

11. See Kenan Malik’s Enemies of free speech, Index on Censorship, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2012.

12. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers’.

13. Flemming Rose, cultural editor of the Danish newspaper JyllandsPosten, in Kenan Malik’s essay Enemies of free speech, Index on Censorship, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2012.

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, mobile, Press Releases

* South American cartoonist and mafia investigator shortlisted for 2015 Freedom of Expression award

* Other nominees include a jailed Moroccan rapper, the lawyers who fought Turkey’s social media ban, and a Mexican news platform fighting cartel-enforced media blackouts

* Judges include Martha Lane Fox, Mariane Pearl, Keir Starmer, and Elif Shafak

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for depicting government corruption, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning charity Index on Censorship. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism; arts; campaigning; and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of a unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist “Bonil” – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad ‘El Haqed’ Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who successfully overturned Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatagr who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

More detail about the nominees is included below.

The winners will be announced at a ceremony at The Barbican, London, on March 18.

The judges for this year’s awards – now in their 15th year – are digital campaigner and entrepreneur Martha Lane Fox; bestselling Turkish novelist Elif Shafak; journalist and campaigner Mariane Pearl; and human rights lawyer Keir Starmer.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact: David Heinemann on 0207 260 2660. Photos of the nominees are available at www.indexoncensorship.org

Notes for editors

The shortlisted nominees:

Journalism

Lirio Abbate (Italy);

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia);

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola);

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

Arts

“Bonil” (Ecuador);

Panti Bliss (Ireland);

Songhoy Blues (Mali);

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia);

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey);

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan);

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany);

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia (Russia)

Digital Advocacy

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary);

Nico Sell (USA);

Syria Tracker (Syria);

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

Index on Censorship, founded in 1972 by poet Stephen Spender, campaigns for freedom of expression worldwide. Its award-winning quarterly magazine has featured writers such as Vaclav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Philip Pullman, Salman Rushdie, Aung San Suu Kyi and Amartya Sen.

The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards are now in their 15th year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim, and Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

The awards are sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers (sponsors of the Campaigning award); The Guardian newspaper group (sponsors of the Journalism award); Google (sponsors of the Digital Advocacy award); and Sage Publications. The Digital Advocacy award is decided by public vote between January 27 and February 15.

Nominees for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015

Journalism

Lirio Abbate

Lirio Abbate is a Rome-based journalist working for the weekly news magazine L’Espresso. He specialises in investigating the criminal activity and political connections of Italian mafia groups, from whom he is routinely subjected to violent threats. Abbate has written four books about mafia groups since 1993. The most recent, Fimmine Ribelli or Rebel Women (2013), illustrates the severe plight of women living under the sway of the ‘Ndrangheta’ – the Calabrian mafia. Abbate is also a leading member of press freedom NGO Ossigeno Per L’informazione (Oxygen via information). In 2011 he founded an anti-mafia literary festival called Trame, which has taken place annually in the heart of Calabrian mafia territory.

Safa Al Ahmad

Safa Al Ahmad has spent the last three years covertly filming an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province. Her 30-minute documentary, Saudi’s Secret Uprising, was broadcast in May 2014, and has drawn wide attention to the violent and bloody protests. Al Ahmad took enormous risks in her regular filming trips. First, as a woman travelling alone, she drew the attention of Saudi officials in a country in which women have limited control over their day-to-day lives. Second, she carried a camera full of footage of dissent. Saudi Arabia is ranked by Freedom House as one of the most restrictive Arabic countries in terms of free expression – Al Ahmad would almost certainly have faced severe punishment if caught filming.

Rafael Marques de Morais

Rafael Marques de Morais is an Angolan journalist and human rights activist. Since 2008 he has run anti-corruption watchdog news site, MakaAngola.org. Marques de Morais exposes government and industry corruption, as well as human rights violations. In 1999, he was arrested and detained for 40 days without charge, and denied food and water for days at a time, following an article critical of the Angolan president. His six-month sentence for defamation was finally suspended on condition that he wrote nothing critical of the government for five years. Within three years he was again reporting abuses. He currently faces nine charges of defamation for reports on human rights abuses committed during diamond mining operations.

Ekho Mosky (Echo of Moscow)

An independent Russian radio station, Echo is one of few media outlets that is critical of Vladimir Putin’s regime and describeded by many as the last bastion of free speech in the country. It has an estimated audience of 7 million people across Russia. Echo was set up in 1990 by radio veterans jaded with Soviet propaganda, and has taken an interrogative stance towards Russia’s government ever since. Its focus is on maintaining balance – it airs pro- and anti-Kremlin voices in equal measure. Editor-in-chief Alexei Venediktov has often battled with Putin. In 2012 Putin remarked that Ekho served foreign interests and “pour[ed] diarrhoea over me day and night”.

Arts

Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla

Bonil is the pen name of Xavier Bonilla, an Ecuador-based editorial cartoonist who draws for several national newspapers, particularly El Universo. For thirty years he has critiqued, lampooned and ruffled the feathers of Ecuador’s political leaders, earning a reputation as one of the wittiest and most fearless cartoonists in South America. More recently, Bonil has gained a new epithet – ‘the pursued cartoonist’ is how Spanish newspaper El Pais styled him in its list of the 12 Latin Americans in 2014 news. Twice in 2014 incumbent president Rafael Correa publicly denounced Bonil and threatened him with legal action – the first case was successful against Bonil, and the second is ongoing.

Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat

El Haqed, roughly translated as ‘the enraged’, is a Moroccan rapper and human rights activist. His music has publicised widespread poverty and endemic government corruption in Morocco since 2011, when his song ‘Stop the Silence’ galvanised Moroccans to protest against their government. He has been imprisoned on spurious charges three times in as many years, most recently for four months in 2014. Haqed believes that police had been looking for an opportunity to arrest him after the release of ‘Walou’ – Haqed’s 2014 album, which is banned from being sold or played in public. One officer at the scene was heard to say “I have scores to settle with you”. Haqed and his brother were beaten by police as they were detained.

Rory ”Panti Bliss” O’Neill

Rory O’Neill sees his it as his duty as “to say the unsayable”. A Dublin-based stand-up comedian and self-described accidental activist for gay rights, he has performed a comedy drag act under the name Panti Bliss for more than two decades. O’Neill rocketed to international fame in January 2014 after he and national broadcaster RTE were threatened with legal action for defamation following a TV appearance in which he identified homophobic writers and groups in Irish media. RTE edited out the offending segment on its online player, issued an apology and paid six individuals €85,000 of public money to settle the dispute. The apology prompted almost a thousand complaints to the TV station and triggered countrywide debate.

Songhoy Blues

Songhoy Blues is a four-piece “desert blues” band, based in Mali. It is made up of musicians who fled north Mali after militant Islamist groups captured the territory and implemented strict sharia law – including the prohibition of secular music – in spring 2012. Despite the lifting of sharia law many musicians continue to self-censor, fearful of the Islamist groups’ return and retribution. In 2014 Songhoy Blues went on a global tour, and also supported artists such as Damon Albarn and Julian Casablancas across Europe. Mojo magazine has named them one of 10 “new faces of 2015”. Their debut album, Music In Exile, will be released in February, and its lead single – Al Hassidi Terei, produced by Zinner – has received critical acclaim.

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi

Amran Abdundi is a women’s rights activist based in north-eastern Kenya. She runs the Frontier Indigenous Network, an organisation that helps women set up shelters along the dangerous border with Somalia. It offers first aid and support for rape victims, including moving them to a safer part of Kenya. As well as protecting citizens endangered by the guerrilla activities of Al Qaeda-linked group Al Shabaab, the organisation helps those fleeing drought and failed harvests in Somalia. Abdundi has established radio-listening groups for women, in which she encourages them to challenge repression and educates them about diseases such as tuberculosis.

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak

Yaman and Kerem are cyber-law experts and internet rights activists who have campaigned vigorously against the Turkish government’s increasingly restrictive internet access laws. Together, they have raised repeated objections to controversial internet law 5651. This law ostensibly blocks access to child pornography and other harmful content, but it is also used to censor politically sensitive content such as pro-Kurdish or left-wing websites. It has been used to block around 50,000 websites. Their advocacy efforts, including an appeal to Turkey’s highest court, forced the overturn of blocks on Twitter and YouTube in 2014.

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar is an Afghan journalist and the executive director of the media advocacy group Nai Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, which works to develop a free media in Afghanistan as the country develops a peacetime society.

A radio journalist for more than 10 years, Khalvatgar is also a member of Afghanistan’s Foundation Open Society Institute, working as media coordinator and acting country manager. Khalvatgar is also an active member of the Access to Information Law Working Group, a group of more than 15 media professionals and activists working for better access to Information Law in Afghanistan.

“Nazis against Nazis” (ZDK)

Rechts gegen Rechts was a guerrilla event that took place in Wunsiedel, Germany, in November 2014. It was designed to peacefully counter an annual neo-Nazi march through the streets of the small town where Rudolf Hess is buried. For every metre the marchers walked, money was raised for an anti-extremism, Nazi-rehabilitation charity ZDK. ZDK was set up in 2003 to tackle all forms of extremism – particularly religious and nationalist extremism. As well as rehabilitating neo-Nazi defectors, it recently began a project called Hayad – meaning ‘life’ in Arabic – which aims to de-radicalise Muslims who want to leave their families and join jihadist groups.

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia is an NGO network based in Russia, dedicated to improving transparency and exposing human rights abuses in the Russian military. It aims to provide soldiers’ families with reliable information, kept private by the notoriously secretive Russian military. It also provides legal advice for Russian soldiers and their families, and to conscientious objectors.

The first Soldiers’ Mothers groups were established in 1989, in the last days of the Soviet Union. In 2014, members began revealing that their investigations had found that many wounded or killed Russian soldiers had been fighting in Ukraine.

Digital Activism

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky

Atlatszo.hu is an investigative news outlet founded and managed by Tamás Bodoky, the main goal of which is to promote free, transparent circulation of information in Hungary. The website, which receives around 500,000 unique visitors per month, acts as watchdog to a Hungarian government which has increasingly tightened its grip on press freedom in the country. Through it, Bodoky produces investigative reports based on freedom of information requests, and instigates lawsuits in cases where its requests are refused. In 2014, the website has uncovered cases of state control of the media, election fraud, government corruption, tax fraud, and misuse of public funds.

Nico Sell

Nico Sell is a US-based entrepreneur and activist for online privacy and secure digital communication. Sell is the CEO of Wickr, a private messaging app with watertight encryption technology. Messages sent using the app ‘self-destruct’ after a length of time adjusted by the sender – from six days to one second – and are then overwritten by gibberish data on the sender’s and receiver’s phones, making them impossible to recreate. Every year at Defcon, Sell runs a nonprofit training camp for children and teenagers called R00tz Asylum, in which digital skills such as white-hat hacking techniques are taught.

Syria Tracker

Syria Tracker is a crisis-mapping platform, which collates and exhibits live data on human rights abuses and other welfare issues brought about by the Syrian conflict. Reports of killings, rapes, water and food tampering, and chemical attacks ongoing in Syria are geolocated and collated onto a live map by US-based volunteers. Syria Tracker synthesises two pre-existing data-sourcing platforms and this combination makes for meticulous accuracy, since data from one source is triangulated with the other, and unverified information is discarded. The news-tracking tool covers anti- and pro-Assad news sources to reduce potential bias.

Valor por Tamaulipas

Valor por Tamaulipas is a crowd-sourced news platform, based in Mexico and set up in 2012 to fill the void created by the region’s cartel-induced media blackout. Valor’s online followers – more than half a million on Facebook and 100,000 on Twitter – send in reports of cartel-related violence, such as shootings, robberies, or missing people. These reports are immediately curated and disseminated by the page administrator, with a hashtag such as #SDR (“situación de riesgo” i.e. situation of risk) attached. From its inception, Valor por Tamaulipas (which means “Courage for Tamaulipas”) has been under constant threat by cartels.

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

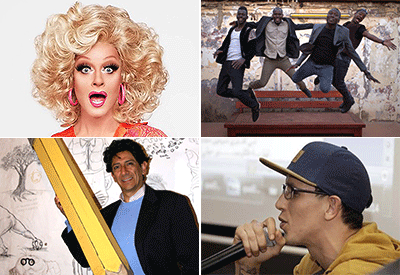

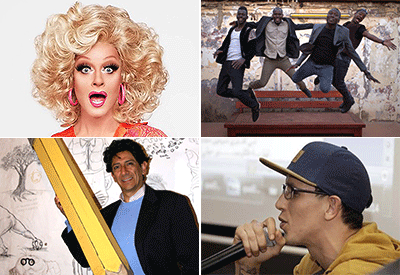

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org