23 Jan 2015 | News and features

Bahrain

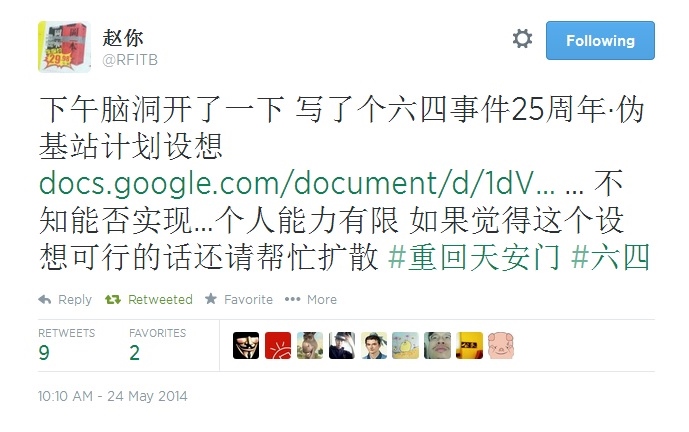

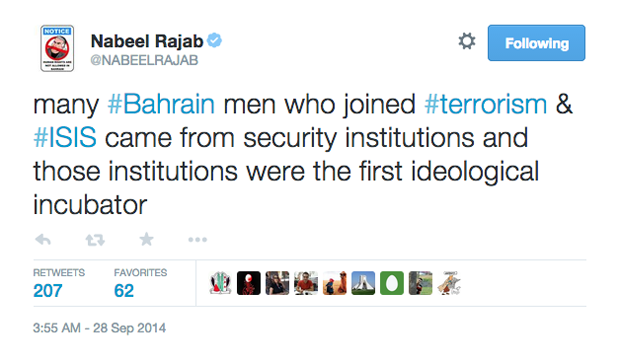

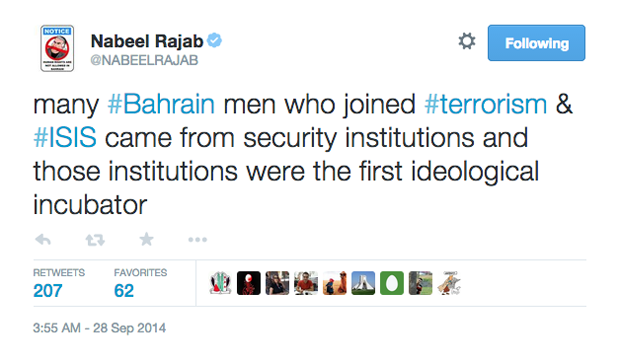

This week, prominent Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence over a tweet in which both the country’s ministry of interior and ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab was only released last May after two years in prison, over charges that included sending offensive tweets. His experience is not unique in Bahrain. In May 2013, five men were arrested for “insulting the king” via Twitter.

Turkey

A former Miss Turkey was recently arrested for sharing a satirical poem criticising the country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on her Instagram account. She is set to go on trial later this year. Turkey has a chequered relationship with social media, temporarily banning both Twitter and YouTube in the wake of the Gezi Park protests, in large part organised and reported through social media. In 2013, authorities arrested 25 individuals for spreading “untrue information” on social media.

Saudi Arabia

(Photo: Gulf Centre for Human Rights)

In late 2014, women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets. The charges against her include “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

France

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)

(Photo: Réseau Voltaire [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the series of terrorist attacks in Paris in early January, at least 54 people have been detained by police for “defending or glorifying terrorism”. A number of the cases, including against comedian Dieudonne M’bala M’bala, are believe to be connected to social media comments.

Britain

A 22 year old man was arrested in for “malicious communication” following Facebook messages made in response to the murder of soldier Lee Rigby, and another user was arrested after taunting Olympic diver Tom Daly about his dead father. More recently, police arrested a 19-year-old man over an “offensive” tweet about a bin lorry crash in Glasgow that killed six people. TV personality Katie Hopkins, known for her controversial tweets, was also reported to Scottish police following some tasteless tweets about about Scots. The incident prompted Scottish police the to post their now infamous tweet declaring they would continue to “monitor comments on social media“.

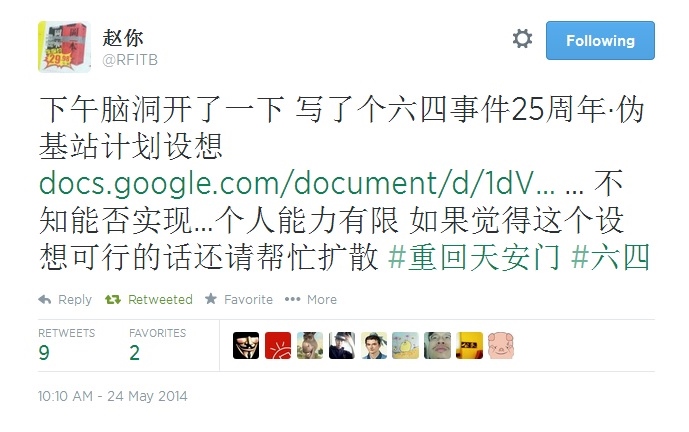

China

Online activist Cheng Jianping was arrested on her wedding day in 2010 for “disturbing social order” by retweeting a joke by her fiance. She was sentenced to one year of “re-education through labour”. Twitter is officially banned in China, and microblogging site Weibo is a popular alternative. In 2013, four Weibo users were arrested for spreading rumours about a deceased soldier labelled a hero and used in propaganda posters. The four were said to have “incited dissatisfaction with the government”, according to the BBC.

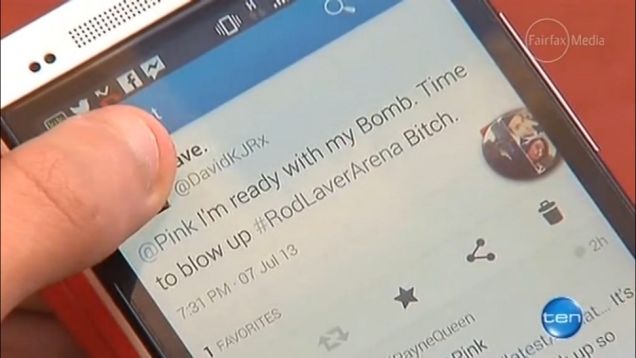

Australia

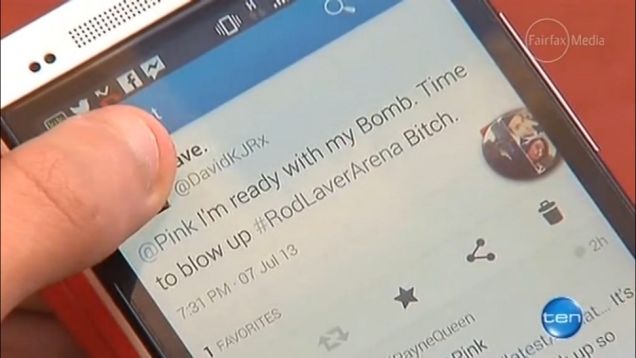

A teen was arrested prior to attending a Pink concert in Melbourne for tweeting: “I’m ready with my Bomb. Time to blow up #RodLaverArena. Bitch.” The tweet referenced lyrics from the American popstar’s song Timebomb.

India

An Indian medical student was arrested in 2012 over a Facebook post questioning why her city of Mumbai should come to a standstill to mark the death of a prominent politician. Her friend was arrested for liking the post. Both were charged with engaging in speech that was offensive and hateful.

United States

Back in 2009, a New York man was arrested, had his home searched and was placed under £19,000 bail for tweeting police movements to help G20 protesters in Pittsburgh avoid the officers. According to Global Voices, it is unclear whether his actions were actually illegal at the time.

Guatemala

A man was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing all their money from banks.

This article was posted on 23 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Nov 2014 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Azerbaijan Statements, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks (Photo: Council of Europe)

I recently returned from one of the most difficult missions of my two-and-a-half year tenure as Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights. In late October I was in Azerbaijan, the oil-rich country in the South Caucasus, which just finished holding the rotating chairmanship of the 47-member Council of Europe. Most countries chairing the organisation, which prides itself as the continent’s guardian of human rights, democracy and the rule of law, use their time at the helm to tout their democratic credentials. Azerbaijan will go down in history as the country that carried out an unprecedented crackdown on human rights defenders during its chairmanship.

All of my partners in Azerbaijan are in jail. It was heart-wrenching to visit Leyla Yunus in pre-trial detention outside of Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital. Head of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, Leyla is Azerbaijan’s most prominent human rights activist and one of three finalists for this year’s prestigious Sakharov award, granted by the European Parliament. I do not know whether it was due to her cataracts or her emotional distress, but she cried throughout our half-hour meeting. The 58-year-old also has diabetes, Hepatitis C and kidney problems. She was in particular anguish for not having had the chance to see Arif, her husband of 26 years, for more than three months. He is also in pre-trial detention, despite having had a stroke just prior to his arrest.

The Yunus couple are among the brave activists in the region that have sought to promote dialogue with their counterparts in Armenia, a country with which Azerbaijan has been at war for the last 25 years over the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which was violently wrested from Azerbaijan as the Soviet Union collapsed. Arif and Leyla Yunus have both been charged with the crime of treason. Leyla regularly compiled lists of the country’s political prisoners for submission to international organisations. On October 24, the day I left Azerbaijan, a Baku court prolonged Leyla’s pre-trial detention for another four months.

Another difficult meeting was with Intigam Aliyev, one of Azerbaijan’s most renowned human rights lawyers, who is also in pre-trial detention for allegedly violating the restrictive provisions that make human rights work virtually impossible in the country. Until his arrest three months ago, Intigam was the co-ordinator of the Council of Europe’s legal training programme in the country. He was also legal counsel for dozens of cases against Azerbaijan before the European Court of Human Rights. When the authorities seized all of his documents, including the case files, he said he felt like the rug had been pulled from under his feet. He did not know how he could continue pushing the cases at the European Court or how he could defend himself. Again, the day I left Azerbaijan, his pre-trial detention was prolonged for another three months. When the judge announced his decision, Intigam nearly fainted.

I had a more upbeat meeting with Anar Mammadli, winner of this year’s Vaclav Havel prize, granted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Anar has already been convicted to a five-and-a-half-year prison sentence for violating the country’s cumbersome NGO laws (the formal charges were tax evasion, illegal entrepreneurship and abuse of authority). Anar was appealing his conviction and was in good spirits, despite the scant chances of success of his appeal. As one of the country’s most professional organisers of election monitoring, Anar had been harshly critical of several previous ballots in the country. Anar spends most of his time exercising and reading books on political science, philosophy and history. He wanted to know how from prison he could provide input to the Council of Europe’s efforts to assist Azerbaijan improve the legal framework for NGOs.

I also left heartened by a meeting with Rasul Jafarov, the head of an NGO called the Human Rights Club. Though he had had his pre-trial detention extended for another three months the day before I met him, Rasul was in good spirits. Rasul made a name for himself by organising a campaign called “Sing for Democracy” in the run-up to the holding of the Eurovision Song contest, which Azerbaijan hosted in 2012. He had planned to organise a new campaign called “Sports for Democracy” in the run-up to the holding of the European Games in Azerbaijan in 2015. Though he is charged with violations of the NGO law, as we bid farewell to each other, he related his plans to organise a human rights NGO among detainees.

While most of my partners are in detention, others discontinued their human rights work, left the country over the summer, or went into hiding as the crackdown spread. I visited one of the activists in hiding, Emin Huseynov, head of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, an NGO defending journalists in Azerbaijan’s restrictive media context. Though Emin is only 35 years old, he has very high blood pressure and an old spinal injury caused by an encounter with Azerbaijani police batons at an “unauthorised” demonstration a few years ago. Doctors who have examined him say he will not survive an Azerbaijani prison.

These are just some of the activists and journalists languishing in prison or under pressure in Azerbaijan. They are core partners for the Council of Europe – they have all attended roundtables for human rights defenders organised by my office or participated in events organised by the Parliamentary Assembly. The Council of Europe’s primary friends and partners in the country have almost all been targeted. While this pains me deeply, it also makes practical cooperation between Azerbaijan and the Council of Europe extremely difficult. The reprisals must stop. Now.

This article was originally posted on the Facebook page of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights. It is republished here with permission from the Council of Europe and the Council of Europe Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights.

20 Nov 2014 | Bahrain, News and features

Update: Bahrain will hold parliamentary elections on Saturday. Opposition groups including Al-Wefaq will boycott the vote, as leading member Abdul-Jalil Khalil told the Associated Press “”These elections are destined to fail because the government is incapable of addressing the political crisis. The next parliament is going to be powerless and unrepresentative.”

In October, a Bahraini court suspended all Al-Wefaq activities for three months, including hosting rallies or press conferences. Just weeks before US State Department official Tom Malinowski was ordered to leave Bahrain after meeting with Al-Wefaq leaders.

In the last elections, held in 2010, before Arab Spring protests, the Bahraini governement claimed 67 percent voter turnout. Many doubt whether turnout will be as great to help narrow down the 419 candidates.

Bahrain human rights activist Zainab Al-Khawaja was released from prison on Wednesday after spending five weeks imprisoned. Al-Khawaja, who is more than eight months pregnant, must return to court on 4 and 9 December for her sentencing.

Al-Khawaja was arrested on 14 October after she ripped a picture of the king in court, where she faced charges for insulting the king.

“I am the daughter of a proud and free man,” Al-Khawaja said in court. “My mother brought me into this world free, and I will give birth to a free baby boy even if it is inside our prisons. It is my right, and my responsibility as a free person, to protest against oppression and oppressors.”

Maryam Al-Khawaja, Zainab’s sister, spoke with Index last month, urging the UK to speak out against human rights violations in Bahrain.

“It isn’t that the people who are being arrested will stop doing what they do, because I don’t think that they will and I think the past four years have been evidence to that,” Maryam said. “My worry is that those people become voiceless. Those people become people who are not heard or seen or cared about. Because that’s when the Bahraini government will find the platform to do whatever they want to do to those people. ”

Maryam also spent time in prison recently and will return to court on 1 December. Their father remains imprisoned.

Nabeel Rajab, President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR), was recently released on bail after his 1 October arrest. Rajab was imprisoned for “denigrating government institutions” on Twitter.

The GCHR released a statement calling for Rajab’s charges to be dropped.

“Bahrain has made international commitments to protect freedom of expression, yet it continues to jail human rights defenders who are simply exercising their right to free speech, whether via twitter or while speaking internationally about Bahrain’s problems,” said Khalid Ibraham, co-director of GCHR.

Rajab must return to court on 20 January 2015 and may not leave Bahrain until then.

Rajab was released in May after spending two years in prison for “making offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests.”

This article was originally posted on 20 Nov 2014 indexoncensorship.org and was updated on 21 Nov 2014.

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)