21 Apr 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

We, representatives of international and national non-governmental organisations, issue this appeal prior to a discussion of the investigation into allegations of corruption at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) in connection with its work on Azerbaijan, at the Assembly’s April 2017 session and a meeting of the Bureau of the Assembly before the session. We call upon you to support a full, thorough and independent investigation into the corruption allegations, with full civil society oversight.

We are extremely concerned about credible allegations presented in a December 2016 report by the European Stability Initiative (ESI), “The European Swamp: Prosecutions, corruption and the Council of Europe” building on previous findings by ESI and others published in 2012-16, detailing improper influencing of Assembly members by representatives of the Azerbaijani government. In particular, the reports include credible allegations that PACE members from various countries and political groups received payments and other gifts with a view to influencing the appointment of Assembly rapporteurs on Azerbaijan, as well as reports and resolutions of the Assembly on Azerbaijan, most notably the PACE vote on the draft resolution on political prisoners in Azerbaijan in January 2013.

The allegations regarding improper conduct of PACE members are serious, credible, and risk gravely undermining the credibility of the Assembly, as well as the Council of Europe as a whole. It is essential that these allegations are investigated thoroughly and impartially. Calls and recommendations for independent investigation into these allegations put forward by ESI have been echoed by many civil society actors, including Amnesty International, Transparency International, and a group of 60 members of Azerbaijani civil society actors and 20 international NGOs.

We welcome the decision of the PACE Bureau on 27 January 2017 to set up an independent investigation body to shed light on hidden practices that favour corruption. The Bureau has also committed to revising the Assembly’s Code of Conduct and invited GRECO (the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption) to provide advice to the Rules Committee, charged with the investigation.

On 3 March, Wojciech Sawicki, PACE Secretary General, presented the Assembly Bureau with a draft terms of reference for the external and independent investigation at the Bureau meeting in Madrid. The proposal is credible, defining a wide mandate and competences and including strong guarantees for the independence of the investigation and safeguards against non-compliance with its work.

Unfortunately, the proposal was met with resistance at the meeting, and no agreement was made on its substance. The proposal was further discussed at a meeting of the heads of the PACE Parliamentary groups on 28 March in St Petersburg: again, no consensus was reached on its content, and whether it should be adopted.

A thorough investigation is essential to restore PACE’s credibility and allow it to effectively address human rights violations across the Council of Europe, including in Azerbaijan. The chairman of Azerbaijani NGO the Institute for Reporters Freedom and Safety, Mehman Huseynov is already facing reprisals for raising the corruption allegations during the January PACE session. A day after his NGO sent a letter about the corruption allegations to PACE members in January, he was abducted and tortured by police and later sentenced for 2 years on defamation charges for allegedly making false allegations about torture. For PACE to be in a position to respond to such violations, it must be seen as independent and not under the influence of states wishing to influence their conduct.

We call upon members of the PACE Bureau to commit to the Sawicki proposal and to call for a full plenary debate on the proposal at the April session of PACE. We also call on the PACE Bureau to include a mechanism of civil society oversight of the investigation to ensure its full independence and impartiality.

We call upon all Members of the Assembly to support in the strongest possible terms an independent, external and thorough investigation. This can be done by signing a written Declaration on the Parliamentary Assembly Integrity introduced on 25 January 2017 by PACE members Pieter Omtzigt (The Netherlands, Christian Democrat), and Frank Schwabe (Germany, Social Democrat) urging the PACE President Pedro Agramunt (Spain, EPP) to launch a “deep, thorough investigation by an independent panel” that makes its findings public. More than one fifth of the Assembly members have joined the declaration. More voices in support of the Assembly integrity are needed. Moreover, PACE members must insist on their right to discuss the Sawicki proposal at the April session of the Assembly, to ensure that PACE has the mechanisms in place to adequately deal with corruption allegations.

We call on the Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjorn Jagland to make a very strong statement to affirm that there will be no tolerance of any corruption, including bribery, trading in influence or taking up of roles that imply a conflict of interest, in the Parliamentary Assembly and the Council of Europe in general.

Commitment to the rule of law, integrity, transparency, and public accountability should be effectively enforced as the key principles of the work of the Parliamentary Assembly. If such a decision is not made now, reputational damage to PACE may become irreparable, preventing PACE from fulfilling its role as a guardian of human rights across the Council of Europe region.

Signatures:

1. The Netherlands Helsinki Committee

2. International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium)

3. Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights (Russia)

4. Freedom Files (Russia/Poland)

5. Norwegian Helsinki Committee

6. Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

7. Analytical Center for Interethnic Cooperation and Consultations (Georgia)

8. Article 19 (UK)

9. The Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House (Belarus/Lithuania)

10. Index on Censorship (UK)

11. Human Rights House Foundation (Norway)

12. Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

13. PEN International (UK)

14. Crude Accountability (USA)

15. Legal Transformation Center (Belarus)

16. Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

17. World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) (Switzerland)

18. The Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

19. Belarusian Helsinki Committee

20. Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

21. Promo LEX (Moldova)

22. Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights (Germany/Switzerland)

23. Public Association “Dignity” (Kazakhstan)

24. Human Rights Monitoring Institute (Lithuania)

25. Swiss Helsinki Committee

26. Human Rights Information Center (Ukraine)

27. Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

28. Albanian Helsinki Committee

29. Kharkiv Regional Foundation “Public Alternative” (Ukraine)

30. Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (Poland)

31. Women of Don (Russia)

32. DRA – German-Russian Exchange (Germany)

33. Association UMDPL (Ukraine)

34. European Stability Initiative (Germany)

35. International Media Support (IMS) (Denmark)

36. Civil Rights Defenders (Sweden)

37. International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) (France)

38. Sova Center for Information and Analysis (Russia)

39. Kosova Centre for Rehabilitation of Torture Victims (Kosovo)

40. Truth Hounds (Ukraine)

41. People in Need Foundation (Czech Republic)

42. Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum (Belgium)

43. Macedonian Helsinki Committee

44. International Youth Human Rights Movement

45. Human Rights First (USA)

46. Regional Center for Strategic Studies (Georgia/Azerbaijan)

47. Human Rights Club (Azerbaijan)

48. Institute for Reporters Freedom and Safety (IRFS) (Azerbaijan)

49. Media Rights Institute (Azerbaijan)

50. Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy (Azerbaijan)

51. Institute for Peace and Democracy (Netherlands/Azerbaijan)

52. Turan News Agency (Azerbaijan)

53. Democracy and NGO development Resource Center (Azerbaijan)

54. Youth Atlantic Treaty Association (Azerbaijan)

55. Monitoring Centre for Political Prisoners (Azerbaijan)

56. Azerbaijan without Political Prisoners (Azerbaijan)

13 Apr 2017 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Pushkin Club, Rights in Russia and Index on Censorship are proud to invite you to this evening in conversation with Anastasia Zotova.

Pushkin Club, Rights in Russia and Index on Censorship are proud to invite you to this evening in conversation with Anastasia Zotova.

An opportunity to meet someone whose name has been constantly in the news since Ildar Dadin was arrested under a new law banning solitary protests in Russia.

A journalist covering Dadin’s courageous one-man pickets against the Putin regime and the war in Ukraine, Zotova married the detained Dadin in late 2015 and continued to publicise his plight after his imprisonment in a penal colony in Karelia, where he was tortured, and his subsequent transfer to another camp in southern Siberia. Husband and wife have done more than anyone, arguably, to expose conditions in Russia’s large and brutal penitentiary system which today holds dozens more political prisoners.

The event will be held both in English and in Russian with translation.

This is a Pushkin Club event and all are welcome.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

When: Thursday 20 April 7:30pm

Where: Pushkin House, 5a Bloomsbury Square, WC1A 2TA

Tickets: Free. Registration required: [email protected]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492103802860-b443cf38-52ba-4″ taxonomies=”7″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Mar 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

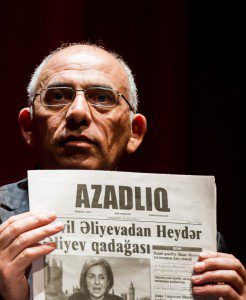

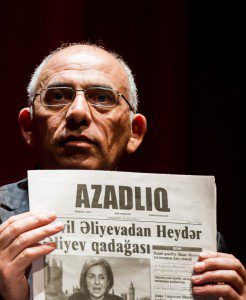

Rahim Haciyev, acting editor-in-chief of 2014 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winning Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Civil, political and human rights are harshly restricted and frequently violated in Azerbaijan. Independent and critical journalists frequently find themselves — or their families — targeted.

Rahim Haciyev, acting editor in chief of the Index Award-winning independent newspaper Azadliq, was forced to flee Azerbaijan after years of official harassment. The government has repeatedly cracked-down on dissent.

Haciyev wrote to Index on Censorship from exile in a western European country:

I’m very sorry that the repressive policy of the Azerbaijani authorities against the Azadliq newspaper forced me to leave the country.

After the arrest of the newspaper’s financial director Faig Amirli, the authorities soon stopped issuing a print version. Amirli was arrested on obviously fabricated charges. I was summoned several times to the prosecutor’s office several times to testify about the paper’s financial affairs. The prosecutors said that this was connected with the criminal case of Amirli, but are invesitgating him under charges of “inciting religious hatred” and “violating the rights of citizens under the pretext of conducting religious rights”.

It turned out that they were interested in the financial issues of the newspaper in order to find a way to silence it. In addition, several employees of the newspaper were summoned for questioning. Then a court ordered tax authorities to comb through the paper’s financial activities. It’s clear that this was undertaken to increase pressure on the newspaper and me personally.

Aiming to cripple Azadliq, the government-owned distribution company was ordered to withhold circulation receipts — $84,000. So we weren’t able to print or even pay our bills. Three staffers are in prison — Seymur Hezi, Faig Amirli and Elchin. Each of them had sharply criticised the lawlessness and corruption of Azerbaijani officials.

In February, 11 Azadliq employees were summoned to the prosecutor’s offices to be interrogated again. Several government agencies increased their pressure on the newspaper’s online operation.

I had been warned twice in the past two years by the prosecutor general’s office that under my leadership Azadliq had been slandering Azerbaijani authorities. In their notices I was told that failure to comply with their terms would mean legal repercussions for me. But I refused. The newspaper continued to report on corruption, abuses of power and the absence of the rule of law. We were devoted to pursuing the truth.

And that is why the authorities intensified repression against the newspaper. Now this lawlessness has forced me to leave the country.

This decision was extremely difficult. I am cut off from my family and friends. I have two children and don’t know when I will see them again.

But despite all the problems I will continue to work daily for the newspaper’s website.

It’s my job, this is my job, this is my life.

Rahim Haciyev

Acting Editor-in-Chief, Azadliq

Haciyev is just one of the many journalists who have been targeted by Azerbaijani authorities in recent years. The country is ranked 163rd out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2016 World Press Freedom Index, which ranks 180 countries according to the level of freedom available to journalists. Almost everyone who speaks out against the regime of President Ilham Aliyev, including journalists, human rights defenders, activists and bloggers, are commonly imprisoned on spurious charges, such as drug and weapon possession, hooliganism and tax evasion. Reports of torture and abuse are typical by those being detained. At least 15 Azerbaijani prisoners of conscience currently remain in jail, including:[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Mehman Huseynov (Twitter)

Mehman Huseynov, an Azerbaijani journalist and pro-opposition blogger, was sentenced to two years in jail on 3 March by a Baku court for defaming the police chief of the city’s Nasimi district. Huseynov intends to appeal his sentencing. According to Front Line Defenders, a group of police officers violently attacked Huseynov on 9 January. The next he was brought to court, found guilty of disobeying police orders and fined 200 manat (£96). [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Founder and editor of online news portal Kend.info Elchin Ismayilli was arrested on 17 February on charges of “extorting money” and “aggravated abuse of a position of influence”. According to the Caucasian Knot, he was also accused of blackmailing a local office, charges he insists were fabricated to silence his coverage of local corruption and human rights violations. On 18 February, Ismayilli was sentenced to a pre-trial detention period of 24 days. He has previously been subject to multiple arrests and cases of harassment related to his work as a journalist.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

On 3 March, a court decided to prolong the period of investigation of Faig Amirli for three months, the Azerbaijan Press Agency reported. Amirli, financial director of newspaper and assistant chairman of the Azerbaijani Popular Front Party (APFP), was arrested on 20 August 2016 for “inciting religious hatred” and “violating the rights of citizens under the pretext of conducting religious rights,” according to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Writer and blogger Rashad Ramazanov was arrested on 9 May 2013 and sentenced to nine years in prison. According to English PEN, his charges included “illegal possession and sale of drugs”. Police claimed to have found nine grams of heroin on his body, although Ramazanov insists that the drugs were planted by the officers, who he claims also beat him up and tortured him during interrogation. Ramazanov was sentenced to nine years in prison in November 2013 on a trumped-up drug trafficking charge. PEN International reported that on 23 January Ramazanov was moved to solitary confinement for 15 days, the reason for which remains unknown. On 7 February Ramazanov was released from solitary confinement, and his family was given permission to visit him.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Founder and editor of the website Azel, Afgan Sadygov, was sentenced on 12 January to 2.5 years in jail. Sadygov was arrested on 22 November 2016 based on accusations of “hooliganism” after he was attacked on 9 August 2016 and allegedly hit a woman, Contact Online news reported. Sadygov’s website often reports on issues such as poor infrastructure maintenance, bad quality of roads and waste of public funds in Azerbaijan’s Jalilabad region.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Seymur Hezi

According to MeydanTV, the Supreme Court will hear the appeal of Seymur Hezi, reporter for opposition news source Azadliq and presenter for critical TV program “Azerbaycan Saati” on 13 April. The journalist was sentenced to five years in prison on 29 January 2015 on a trumped-up charge of aggravated hooliganism, Index on Censorship reported. The charge came after Hezi was attacked on 29 August by Maherram Hasanov, a complete stranger, and defended himself. Hezi has accused President Ilham Aliyev and chief of staff Ramiz Mehdyev of ordering his arrest.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

The lawyer of Nijat Aliyev, former chief editor of religious website Azadxeber.org, has not been able to get hold of the text of the verdict of the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan for his client, Contact Online news reported. Aliyev’s lawyer believes that the delay has been intentional in order to prevent the filing of a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights, Contact Online news reported. According to IRFS, Aliyev was detained on 20 May 2012 and sentenced to 10 years in prison on 9 December 2013 on charges of illegal possession of drugs and weapons, incitement of religious hatred, calls to seize power and distributing banned religious literature. Aliyev’s website previously published criticisms of the government’s policies in regards to religion, the possibility of a LGBT parade in Baku and the allotment of too much funding for the Eurovision Song Contest in 2012, OCCRP reported.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Alexander Lapshin (BBC)

Russian-Israeli travel blogger Alexander Lapshin was extradited from Belarus to Azerbaijan on 7 February. He faces up to five years in prison on charges of “public calls against the state” and “unauthorised crossing of borders,” according to Armenian News Agency ArmenPress. These charges came after Lapshin traveled to the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and sympathised in his blog entries with the Armenians he met, GlobalResearch reported. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Fikrat Faramazoglu, editor-in-chief of news website jam.az, has been detained since 30 June 2016 on the charge of extortion by means of threats, which is punishable by up to five years in prison. According to Azerbaijan Free Expression Platform, these charges originated when a local restaurant owner accused Faramazoglu of extorting money from him when asked to remove defamatory articles about the restaurant on websites owned by the journalist.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Blogger and social media activist Abdul Abilov has been imprisoned since 22 November 2013. According to Azerbaijan Free Expression Platform, Abilov was charged with illegal possession, storage and manufacturing or sale of drugs when authorities claim to have found illegal drugs in his home and on his person, which Abilov continues to protest were planted on him. On 27 May 2014 Abilov was sentenced to five-and-a-half years in prison. Stop Sycophants!, the Facebook page previously run by Abilov, was shut down following his arrest, IRFS reported. The page was known to strongly criticise authorities.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Mar 2017 | Belarus, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned members of the Civic Solidarity Platform (CSP), a coalition of human rights NGOs from Europe, the former Soviet Union region and North America, and other non-governmental organisations decry the mass detentions of peaceful demonstrators, journalists and human rights defenders, as well as the use of violence and abusive treatment targeting them in Belarus on 25-26 March 2017. These events were the culmination of a series of repressive measures taken by the authorities of the country since the beginning of March to stifle the public expression of grievances. Given the severity of this human rights crisis of unprecedented scale since December 2010, it is crucial that the international community takes resolute action to push for an end to the crackdown in Belarus and justice for those targeted by it.

We condemn the gross violations of the right to peaceful assembly, freedom of expression, freedom from arbitrary detention, and the right to fair trial in Belarus in connection with the recent peaceful protests, and call on the international community to use all available means to put pressure on the Belarusian authorities to immediately end these violations.

Such measures by the authorities should include:

- immediately releasing those currently behind bars because of their involvement in the peaceful protests or their efforts to monitor them;

- dropping charges against all those prosecuted on these grounds;

- carrying out prompt, thorough and impartial investigations into all allegations of arbitrary detention, ill-treatment and other violations of the rights of protesters, passers-by, journalists, human rights defenders and political activists in connection with the protests; and

- bringing those responsible for violations to justice.

We call in particular for the following concrete actions by international community in response to the current crackdown in Belarus:

To the OSCE:

- The OSCE participating States should initiate and support the renewal of the Moscow Mechanism in relation to Belarus and the appointment of a new rapporteur for this process, in view of the fact that the current developments mirror those on the grounds of which this mechanism was invoked in 2011;

- The OSCE Chairmanship should appoint a Special Representative on Belarus, whose mandate should include investigating the recent violations;

- The Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights should monitor the trials of those facing charges because of their participation in the recent peaceful protests, or their efforts to monitor and report on them;

- The OSCE Parliamentary Assembly should reconsider holding its annual session in Minsk in July 2017 and identify another host country and city for this event.

To the Council of Europe:

- The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe should replace its current rapporteur on the situation in Belarus, ensuring that the individual holding this position forcefully speaks out against human rights violations in the country.

To the UN:

- Members of the Human Rights Council should extend the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Belarus, continue urging the Belarusian authorities to allow the Special Rapporteur to visit the country, and adopt a strong resolution on the human rights situation in Belarus at the next session of the Council;

- High Commissioner on Human Rights should publicly condemn the crackdown in Belarus and engage in direct contact with the Belarusian authorities on this matter.

To international financial institutions:

- International financial institutions should apply strong human rights conditionality in the implementation of their programs in Belarus and refrain from allocating funding to government projects until the human rights situation in the country has substantially improved. Specifically, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development should reinstate its calibrated strategy on Belarus.

To the EU:

- The EU member states and institutions should apply stronger and more consistent human rights conditionality to the development of its relations with Belarus and consider the prospects of reinstating sanctions similar to those applied in 2011-12 for widespread human rights violations.

To the USA:

- The US government should consider reinstating the sanctions against Belarus that it suspended in 2015-16.

Background information, based on reports from the ground:

In the afternoon of 25 March 2017, people took to the streets in the Belarusian capital of Minsk for planned peaceful protests on the occasion of the Day of Freedom, which commemorates the Belarusian declaration of independence in 1918. There was as a heavy police and security presence in the city, the downtown area where protests were due to be held was cordoned off, and traffic was blocked on the main Independence Avenue. Local and international human rights monitors representing the CSP member organisations documented the use of heavy-handed tactics by the law enforcement and security authorities to prevent the peaceful protests, for which authorities had not given advance permission as required by Belarusian law and in violation of international standards. At least 700 people were detained on 25 March, including elderly and passers-by. As can be seen on available photos and footage, police forcefully rounded up and beat protesters with batons, although these made no resistance. More than 30 journalists and photographers from both Belarusian and international media outlets were detained; cameras and other equipment of some of them were damaged by police. Toward the evening, police started releasing detainees from the detention facilities, in many cases without charge. However, others remain in detention, and dozens of individuals are expected to stand trial starting Monday 27 March on charges relating to their participation in the peaceful protests.

The following episode requires particular attention: At 12.45 pm local time on 25 March, about an hour before the start of the planned peaceful protest, anti-riot police raided the offices of the Human Rights Center Viasna and detained a total of 57 Belarusian and foreign human rights defenders and volunteers as well as journalists. Human rights defenders and volunteers had gathered there for a training on monitoring the protests and were planning to go to the streets of Minsk for observation of the assemblies. Among them were representatives of Viasna, the Belarusian Helsinki Committee, the Belarusian Documentation Center, Frontline Defenders, International Partnership for Human Rights and other organisations. The police shouted at all present, intimidated them, and ordered to lie down on the floor face down. 57 people were detained without any charges, packed in the buses and brought to the Pervomaisky district police station, where their belongings were searched and their personal information recorded. The detainees were held there for two and a half hours and were released afterwards without charges. One of the detained needed medical treatment because of injuries sustained when being beaten by police. The raid of the offices of Viasna and the detention of the monitors were clearly aimed at intimidating and preventing them from observing the peaceful assembly and documenting possible violations.

The crackdown continued on 26 March, with dozens of people being detained by police as they gathered at October Square in Minsk at noon to express solidarity with those detained the day before. Among the detained on 26 March were at least one human rights defender, one civil society activist and one journalist. Representatives of national and international human rights NGOs, including members of the CSP, continue to document violations perpetrated in connection with the events of the last few days.

The detentions on 25-26 March followed the earlier detention of about 300 people, including opposition members, journalists and human rights defenders in the last few weeks. These detentions have taken place against the background of a wave of peaceful demonstrations that were carried out across Belarus since mid-February 2017 to protest against so-called “social parasites” law which imposes a special tax on those who have worked for less than six months during the year without registering as unemployed. The legislation, which has affected hundreds of thousands of people in the economically struggling country, has caused widespread dismay. On 9 March, President Lukashenko suspended the implementation of the law but refused to withdraw it, resulting in further protests. Many of those detained have been fined or arrested for up to 15 days on administrative charges related to their participation in the peaceful protests. Over two dozen people are facing criminal charges on trumped-up charges of preparation to mass riots.

Signed by the following CSP members:

- Analytical Center for Inter-Ethnic Cooperation and Consultations (Georgia)

- Article 19 (United Kingdom)

- Association UMDPL (Ukraine)

- Bir Duino (Kyrgyzstan)

- Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

- Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

- Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights (Russia)

- Committee against Torture (Russia)

- Crude Accountability (USA)

- Freedom Files (Russia/Poland)

- German-Russian Exchange – DRA (Germany)

- Helsinki Association of Armenia

- Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

- Helsinki Committee of Armenia

- Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia

- Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (Poland)

- Human Rights Center of Azerbaijan

- Human Rights First (USA)

- Human Rights House Foundation (Norway)

- Human Rights Information Center (Ukraine)

- Human Rights Monitoring Institute (Lithuania)

- The institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (Azerbaijan/Georgia/Switzerland)

- Index on Censorship (United Kingdom)

- Institute Respublica (Ukraine)

- International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium)

- Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

- The Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims

- Macedonian Helsinki Committee

- Moscow Helsinki Group (Russia)

- The Netherlands Helsinki Committee

- Norwegian Helsinki Committee

- Office of Civil Freedoms (Tajikistan)

- Promo-LEX (Moldova)

- Protection of Rights without Borders (Armenia)

- Public Association “Dignity” (Kazakhstan)

- Public Alternative Foundation (Ukraine)

- Public Foundation Golos Svobody (Kyrgyzstan)

- Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

- Regional Center for Strategic Studies (Azerbaijan/ Georgia)

- Serbian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights

- SOLIDARUS e.V. (Germany)

- The Swiss Helsinki Committee

- Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

- World Organisation against Torture (OMCT)

Other organisations who have joined the statement:

- Belarus Free Theatre

- Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights (Switzerland)

- PEN International

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490686433484-ad7cf42c-cf25-10″ taxonomies=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Pushkin Club, Rights in Russia and Index on Censorship are proud to invite you to this evening in conversation with Anastasia Zotova.

Pushkin Club, Rights in Russia and Index on Censorship are proud to invite you to this evening in conversation with Anastasia Zotova.