28 May 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, United States

Last week saw a flurry of legislative to-and-fro on the Hill as the US House of Representatives pondered the passage of legislation aimed at ending bulk-collection by the US National Security Agency. The USA Freedom Act, or HR. 3361, was passed on Thursday in a 303-121 vote, and was hailed by The New York Times as “a rare moment of bipartisan agreement between the White House and Congress on a major national security issue”. Congressman Glenn ‘GT’ Thompson (R-Pa.) tweeted that he was the proud cosponsor of a bill “that passed uniting and strengthening America by ending eavesdropping/online monitoring.”

It was perhaps inevitable that compromise between the intelligence and judiciary committees would see various blows against the bill in terms of scope and effect. When legislators want to posture about change while asserting the status quo, ambiguity proves their steadfast friend. After all, with the term “freedom” in the bill, something was bound to give.

Students of the bill would have noted that its main author, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wi.), was also behind HR. 3162, known more popularly as the USA Patriot Act. Most roads in the US surveillance establishment tend to lead to that roughly drafted and applied piece of legislation, a mechanism that gave the NSA the broadest, and most ineffective of mandates, in eavesdropping.

Then came salutatory remarks made about the bill from Rep. Mike Rogers[2], who extolled its virtues on the House floor even as he attacked the Obama administration for not being firm enough in holding against advocates of surveillance reform. There is a notable signature change between commending “a responsible legislative solution to address concerns about the bulk telephone metadata program” and being “held hostage by the actions of traitors who leak classified information that puts our troops in the field at risk or those who fear-monger and spread mistruth to further their misguided agenda.”

Even as Edward Snowden’s ghost hung heavy over the Hill like a moralising Banquo, Rogers was pointing a vengeful finger in his direction. There would, after all, have been no need for the USA Freedom Act, no need for this display of lawmaking, but for the actions of the intelligence sub-contractor. Privacy advocates would again raise their eyebrows at Rogers’s remarks about the now infamous Section 215 telephone metadata program under the Patriot Act, which had been “the subject of intense, and often inaccurate, criticism. The bulk telephone metadata program is legal, overseen, and effective at saving American lives.”

Such assertions are remarkable, more so for the fact that both the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board and the internal White House review panel, found little evidence of effectiveness in the program. “Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act,” claimed the PCLOB, “does not provide an adequate basis to support this program.” Any data obtained was thin and obtained at unwarranted cost.

Critics of the bill such as Centre for Democracy and Technology President Nuala O’Connor expressed concern at the chipping moves. “This legislation was designed to prohibit bulk collection, but has been made so weak that it fails to adequately protect against mass, untargeted collection of Americans’ private information.” In O’Connor’s view, “The bill now offers only mild reform and goes against the overwhelming support for definitively ending bulk collection.”

Not so, claimed an anonymous House GOP aide. “The amended bill successfully addresses the concerns that were raised about NSA surveillance, ends bulk collections and increases transparency.” Victory in small steps would seem to have impressed the aide. “We view it as a victory for privacy, and while we would like to have had a stronger bill, we shouldn’t let the perfect being the enemy of the good.”

Various members of the House disagreed. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) noted that the bill had received a severe pruning by the time it reached the House floor, having a change “that seems to open the door to bulk collection again.” Others connected with co-sponsoring initial versions of the bill, among them Rep. Jared Polis (D-Colo.) and Rep. Justin Amash (R-Mich.) also refused to vote for the compromise.

What, then, is the basis of the gripe? For one, the language “specific selection term”, which would cover what the NSA can intercept, is incorrigibly vague. The definition offers the unsatisfactory “term used to uniquely describe a person, entity or account.” What, in this sense, is an entity for the purpose of the legislation? The tip of the iceberg is already problematic enough without venturing down into the murkier depths of interpretation.

Even more troubling in the USA Freedom Act is what it leaves out. For one thing, telephony metadata is only a portion of the surveillance loot. Other collection programs are conspicuously absent, be it the already exposed PRISM program which covers online communications, Captivatedaudience, a program used to attain control of a computer’s microphone and record audio, Foggybottom – used to note a user’s browsing history on the net, and Gumfish, used to control a computer webcam. (These are the choice bits – others in the NSA arsenal persist, untrammelled.)

Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Amendments (FISA) Act, the provision outlining when the NSA may collect data from American citizens in various cases and how the incorrect or inadvertent collection of data is to be handled, is left untouched. On inspection, it seems the reformist resume of the Freedom Act is rather sparse.

Ambiguities, rather than perfections, end up being the enemy of the good. Laws that are poorly drafted tend to be more than mere nuisances – they can be dangerous in cultivating complacency before the effects of power. Well as it might that the USA Freedom Act has passed, signalling a political will to deal with bulk-collection of data. But in making that signal, Congress has also made it clear that compromise is one way of doing nothing, a form of sanctified inertia.

This article was posted on May 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 May 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, Spain, Turkey

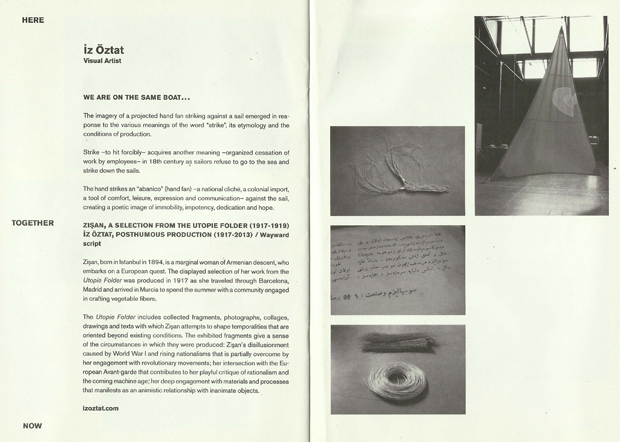

Last year, the exhibition Here Together Now was held at Matadero Madrid, Spain. Curated by Manuela Villa, it was realised with the support of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, Turkish Airlines and ARCOmadrid. But in the exhibition booklet, the explanatory notes to artist İz Öztat’s work “A Selection from the Utopie Folder (Zişan, 1917-1919)” was censored upon the request of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, and the expressions “Armenian genocide” and the date “1915” were taken out.The case shows how the Turkish state delimits artistic expression in the projects it supports, and how it silences the institutions it cooperates with.

After Turkey was chosen as the country of focus for the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid International Contemporary Art Fair, the designated curator Vasıf Kortun and assistant curator Lara Fresko started to work with the galleries that would join the fair. They helped in fostering connections between the Madrid arts institutions and artists in Turkey; as well as with the embassy officers in charge of the financial support of events such as Here Together Now, which would run as a parallel event to the main fair. The embassy indicated that it would support this exhibition with the generous sum of €250,000. However, it did not provide any written documentation guaranteeing this support, and outlining the mutual duties and responsibilities of the parties involved. Likewise, during the realisation of the project, there was no written communication between the embassy and Matadero Madrid, and all negotiations took place verbally, over the phone. It was in this manner that, from the very beginning, the state kept the exact conditions of its support ambiguous and created a tense situation for the organisers. Ultimately, this working practice gave the Embassy the possibility of denying the promised support, in the event that their request was not carried out.

This is not the first case of the Turkish state censoring an arts event it sponsors abroad. We frequently hear about such cases off the record, and at times through the media. One of the best-known cases of state intervention took place in Switzerland, during the 2007 Culturespaces Festival. Director Hüseyin Karabey’s film Gitmek – My Marlon and Brando, which had received support from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, was taken out of the festival program at the very last minute, at the request of an officer from the General Directorate of Promotion Fund, on the pretext that “a Turkish girl cannot fall in love with a Kurdish boy” as was the case in the film. The officer threatened the festival organisers with withdrawal of sponsorship totaling €400,000 — much like the case of the Madrid exhibition. The festival director decided that they could not go ahead with the event without this support, ceded to the censorship request, and accepted to take the film out of the program. However, independent movie theaters in Switzerland criticised this decision and ended up screening the film independently of the festival.

Both examples show that the state controls the content of the projects it sponsors abroad, interferes with the organisations on arbitrary grounds, and violates artists’ rights by threatening the very institutions it collaborates with.

The administrative channel for the state’s support to events outside of Turkey is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Promotion Fund Committee, established under law 3230 (10 June, 1985) with the aim of supporting activities that “promote Turkey’s history, language, culture and arts, touristic values and natural riches”. The Committee reports directly to the Prime Minister’s office, and is presided over either by the Prime Minister himself, the Vice Prime Minister or a minister designated by the PM. It has five more members: Deputy Undersecretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the general managers of the Directorate General of Press and Information, and the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). The objective of the fund is “to provide financial support to agencies set up to promote various aspects of Turkey domestically and overseas, to disseminate Turkish cultural heritage, to influence the international public opinion in the direction of our national interests, to support efforts of public diplomacy, and to render the state archive service more effective”.

The Committee convenes at least four times a year upon the invitation of its president to evaluate project applications. The only criterion in accepting a project is whether it complies with the objectives mentioned above. After the Committee carries out its evaluation, the projects are put into practice upon the approval of the PM. Representative offices of the Promotion Fund Committee monitor whether the projects are implemented in compliance with the principles of the fund. In the case of the Madrid exhibition, the Turkish Embassy assumed the role of representative office. In this respect, as per the relevant regulation, the embassy was in charge of controlling the project, signing protocols with project managers to outline mutual duties and responsibilities, making the necessary payments, and delivering the project report to the Committee. As such, the embassy’s avoidance of all written documentation is in breach of the principles and modus operandi established by its own regulations.

Overall, it can be said that the Promotion Fund Committee does not meet the criteria of transparency and accountability generally expected from a public agency. The dates when the committee convenes to evaluate the projects are not announced, and the committee members, annual budget, sponsorship priorities and selection criteria are not made public. The sums paid to projects sponsored and the content of the projects are not disclosed officially. In other words, there is no transparency about the distribution of the funds, or about the auditing procedures. Such structural problems make it even harder to reveal and question the state’s violation of the right to artistic expression.

Another important aspect of this case is that the state constantly tries to reproduce its dominant discourse based on the denial of past and ongoing human rights violations such as forced displacement, genocide, political murders, burning of villages, enforced disappearances, rape, and torture through security forces; and does its utmost to silence any expression which contests this discourse. The centenary of the Armenian genocide, 2015, is drawing near. As such, it becomes even more important to demand that the Turkish state be held accountable for this human rights violation.

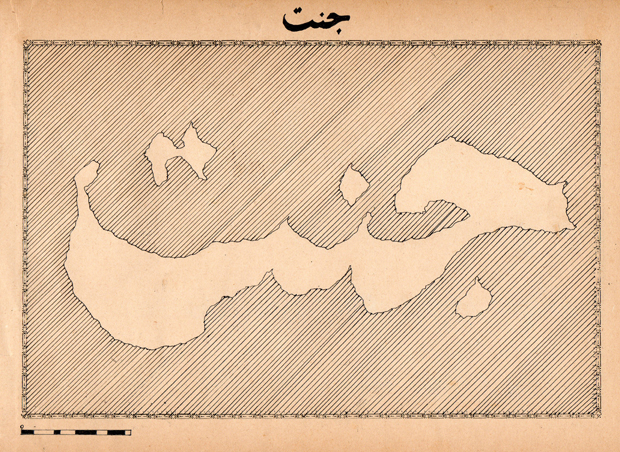

Map of Cennet/Cinnet (Paradise/Possessed Island). Zişan, 1915-1917. Ink on paper, 20×27 cm. Dedicated to the Public Domain

Siyah Bant is a research platform that documents and reports on cases of censorship in arts across Turkey, and shares these with the local and international public. In the context of this work, we wanted to investigate the censorship that occurred at Here Together Now. In accordance with the Right to Information Act, we asked the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to explain the legal basis of the censorship they imposed on the booklet. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicated that Matadero Madrid and curator Manuela Villa were the only authorities in charge of selecting the artists who would participate in the workshops of ARCOmadrid, designating the content of the works to be produced during the workshops, and preparing all printed matter in connection to the event. We were unable to obtain an official statement from curator Manuela Villa, despite several inquiries. Finally, we conducted an interview the artist İz Öztat to understand how the censorship took place, and how she experienced the process.

How did you come to be involved in the exhibition?

I was invited by Manuela Villa, curator of Matadero Madrid, after meeting her in Istanbul. Matadero planned for a residency program and an exhibition project titled Here Together Now to take place concurrently with the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid Art Fair that had a section consisting of invited galleries from Turkey. By the time I signed the contract with Matadero Madrid, I knew that the project was partially supported by the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and Turkish Airlines.

Here Together Now was a process that allocated the resources with an emphasis on living and working together. Cristina Anglada (writer), Theo Firmo, Sibel Horada, HUSOS (a collective of architects), Pedagogias Invisibles (art mediation collective), Diego del Pozo Barrius, Dilek Winchester and I had six weeks together, during which we figured out common concerns, negotiated our relationship to the institution’s public, designed the working and exhibition space, collaborated and produced our works.

Can you tell us about the nature of contract with the institution and if there were any limitations indicated as to the nature of your work?

We signed a very detailed contract with Matadero Madrid that laid out the responsibilities of the institution and the artist in relation to the production and authorship of new work but there were no limitations outlined in the contract. I took it for granted that the artist has freedom of expression and institutions do not interfere in the produced content.

The institution was extremely supportive of the project. They were engaged in our discussions and ready to help once we started producing the work.

Could you talk a bit about the work that you prepared for Matadero Madrid?

The work shown in the Here Together Now exhibition was part of an ongoing process, in which I imagine ways to conjure a suppressed past. Since 2010, I have been engaged in an untimely collaboration with Zişan (1894-1970), who is a recently discovered historical figure, a channeled spirit and an alter ego. By inventing an anarchic lineage with a marginalized Ottoman woman, I try to recognize a haunting past and rework it to be able to imagine otherwise. For the exhibition at Matadero Madrid, I produced and exhibited “A Selection from Zişan’s Utopie Folder (1917-1919)” accompanied by works from the “Posthumous Production Series”, in which I depart from Zişan’s work to open a path towards the future in our collaboration. The exhibited work was complemented by a publication with three interviews, which situates the work and builds a discourse around it.

Which aspect of the work was censored? How did the process of censorship occur, and what kind of dilemmas did you face in this process?

Manuela Villa, the curator, met with me in the exhibition space one evening a few days prior to the opening. Officials from the Turkish Embassy had threatened to withdraw their financial support, if the demanded changes were not made. I had to make a decision on the spot and accepted the censorship in the booklet, but not in the publication complementing the work. The exhibition booklet was reprinted and the sentence was changed to “Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894, is a marginal woman of Armenian descent, who embarks on a European quest.”

As I said before, there was an emphasis on the community we built together during the residency at Matadero and I didn’t want to make a decision alone that would put the whole project at risk. Because of the time constraints, we were only able to meet with the other artists after the opening to discuss the precarious condition that we were all in. The institution didn’t have any signed documents from the Embassy committing to the sponsorship. Everything was communicated verbally and there was no written documentation. I was not able to reach out for a support network to resist the situation, not least due to the immediacy the decision required.

The exhibition booklet that was presented to the embassy was altered but the publication accompanying your work remained unchanged. How did the curator and other artists react to your refusal to change the publication?

I could not stand my ground with regard the exhibition booklet because it concerned everybody in the project. Yet, I was able to take full responsibility of my own work. We were informed that officials from the embassy will visit the show prior to the opening and I was ready to withdraw the work, if there was any interference. Everybody was supportive of my decision.

What happened on the day of the opening? Did you feel the need to prepare yourself?

In the end, none of the officials from the embassy came to the opening or the exhibition. There was no confrontation regarding the work. There might be a few reasons for this that I can think of. Maybe, they felt entitled to interfere with the content of the exhibition booklet because it had the logo of the embassy and could dismiss my publication since it only had the logo of Matadero Madrid. It was not of benefit for the embassy to confront me in a situation that would have made the case public.

As Siyah Bant we inquired both with the curator and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in order to understand how this censoring motion played out. Given that the ministry rejects any responsibility and instead assigns all responsibility to the curator, and that the curator was acting under the duress of loosing all funding last minute, where does this leave you as the artist? How do you make sense of what happened to your work?

Since I accepted the censorship, my only option was making the situation public after the fact. I have been working in cooperation with Siyah Bant since I got back from Madrid. It took a few months to receive an official response from the embassy, which denied all responsibility. We wanted to make the case public after receiving a statement from the curator or the institution. I was unable to receive such a statement, and Siyah Bant is working on that now.

I see it as an experience, in which I was able to test and see the boundaries of government support that is allocated to arts and culture for promoting the country. If you decide to accept this support and challenge official policies, a system of censorship starts to operate.

Next year marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide which will inevitably bring about numerous artistic and cultural reflections on the subject. Given the current climate in Turkey, how confident are you that artistic freedom of expression will be respected?

We are going through a period, in which it is impossible to make predictions about what can happen even the next day. I can only hope that genocide denial at state level comes to an end. I am sure that artists will articulate their own ways of recognising the Armenian Genocide and confronting its denial. You are probably more prepared than I am to predict and know what kinds of mechanisms are at work to limit the production and dissemination of such work.

What would be your recommendations to other artists taking part in cultural events that are supported by the Turkish government?

Based on my experience, I think that artists and art institutions need to act in solidarity in these situations. If there is funding from the Turkish state, the institutions and artists involved need to be aware that the state monitors the content. The various institutions that distribute state funding do not provide written documents about their commitments and communicate their demands mostly in person or by phone. Demanding written documentation at every step is necessary. Artists who are considering to take parts in projects that receive state funding, can demand from the art institutions to be more transparent about the budget and its workings so that they can be prepared to make alternative plans if the state funding does not come through as promised.

If I encountered the same case of censorship now, I would not feel obliged to make a decision immediately and in isolation. I would consult the rest of the group and demand the involvement of the institution.

This article was posted on May 28 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society

Gujarat Chief Minister and BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi filed his nomination papers from Vadodara Lok Sabha seat amid tight security on April 6. (Photo: Nisarg Lakhmani / Demotix)

Electioneering for the Indian elections of 2014 has reached a fever pitch. Never before in the history of modern India has it seemed likely that the country is ready to cut its cord with the Congress Party’s Gandhi family, and never before has its chief opposition party, the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) been projected as the sole inheritance of one man – Narendra Modi.

The “greatest show on Earth” – the Indian elections – is underway. There are 37 days of polling across 9 states, with a 814 million strong electorate, and more than 500 political parties to choose from. The hoardings all seem to scream the “development” agenda, but unfortunately in India, this conversation seems to be skating on thin ice. Cracks quickly appear, and beneath the surface, political parties seem to be indulging in the same hate speech, communal politicking and calculations that work to polarise the electorate and garner votes.

Hate speech in India is monitored by a number of laws in India. These are under the Indian Penal Code (Sections 153[A], Section 153[B], Section 295, Section 295A, Section 298, Section 505[1], Section 505 [2]), the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 95) and Representation of the People Act (Section 123[A], Section 123[B]). The Constitution of India itself guarantees freedom of expression, but with reasonable restricts. At the same time, in response to a Public Interest Litigation by an NGO looking to curtail hate speech in India, the Court ruled that it cannot “curtail fundamental rights of people. It is a precious rights guaranteed by Constitution… We are 128 million people and there would be 128 million views.” Reflecting this thought further, a recent ruling by the Supreme Court of India, the bench declared that the “lack of prosecution for hate speeches was not because the existing laws did not possess sufficient provisions; instead, it was due to lack of enforcement.” In fact, the Supreme Court of India has directed the Law Commission to look into the matter of hate speech — often with communal undertones — made by political parties in India. The court is looking for guidelines to prevent provocative statements.

Unenviably, it is the job of India’s Election Commission to ensure that during the elections, the campaigning adheres to a strict Model Code of Conduct. Unsurprisingly, the first point in the EC’s rules (Model Code of Conduct) is: “No party or candidate shall include in any activity which may aggravate existing differences or create mutual hatred or cause tension between different castes and communities, religious or linguistic.” The third point states that “There shall be no appeal to caste or communal feelings for securing votes. Mosques, churches, temples or other places of worship shall not be used as forum for election propaganda.”

This election season, the EC has armed itself to take on the menace of hate speeches. It has directed all its state chief electoral officers to closely monitor campaigns on a daily basis that include video recording of all campaigns. Only with factual evidence in hand can any official file a First Information Report (FIR), and a copy of the Model Code of Conduct is given along with all written permissions to hold rallies and public meetings.

As a result, many leaders have been censured by the EC for their alleged hate speeches during the campaign. The BJP’s Amit Shah was briefly banned by the EC for his campaign speech in the riot affected state of Uttar Pradesh, that, Shah had said that the general election, especially in western UP, “is one of honour, it is an opportunity to take revenge and to teach a lesson to people who have committed injustice”. He has apologized for his comments. Azam Khan, a leader from the Samajwadi Party, was banned from public rallies by the EC after he insinuated in a campaign speech that the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan had been won by India on account of Muslim soldiers in the Army. The EC called both these speeches, “highly provocative (speeches) which have the impact of aggravating existing differences or create mutual hatred between different communities.”

Other politicians have jumped on the bandwagon as well. Most recently, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s Praveen Togadia has been reported as making a speech targeting Muslims who have bought properties in Hindu neighborhoods. “If he does not relent, go with stones, tyres and tomatoes to his office. There is nothing wrong in it… I have done it in the past and Muslims have lost both property and money,” he has said. There was the case of Imran Masood of the Congress who threatened to “chop into pieces” BJP Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi – a remark that forced Congress’s senior leader Rahul Gandhi to cancel his rally in the same area following the controversy that erupted. Then there is Modi-supporter Giriraj Singh who has said that “people opposed to Modi will be driven out of India and they should go to Pakistan.” In South India, Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) president K Chandrasekhar Rao termed both TDP and YSR Congress (YSRCP) as ‘Andhra parties’ and urged the people of Telangana to shunt them out of the region. The Election Commission has directed district officials to present the video footage of his speeches at public meetings, in order to determine punishment, if needed. Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has been served notice by the EC for calling Narendra Modi a “mass murderer”; a reference to his alleged role in the Gujarat riots of 2002.

Shekhar Gupta, editor of the national paper, the Indian Express has published a piece ominously titled “Secularism is Dead,” but instead appeals to the reader to have faith in Indian democracy far beyond what some petty communal politicians might allow. The fact that the BJP’s Prime Ministerial candidate is inextricability linked in public consciousness to communal riots in his home state of Gujarat has only compounded speeches over and above what people believe is the communal politics of the BJP that stands for the Hindu majority of India. In contrast, many believe that by playing to minority politics, the Congress indulges in a different kind of communal politics. And then there are countless regional parties, creating constituencies along various caste and regional fissures.

However, perhaps the last word can be given to commentator Pratap Bhanu Mehta who writes of the Indian election: “But what is it about the structures of our thinking about communalism that 60 years after Independence, we seem to be revisiting the same questions over and over again? Is there some deeper phenomenon that the BJP-Congress system seems two sides of the same coin to so many, even on this issue? The point is not about the political equivalence of two political parties. People will make up their own minds. But is there something about the way we have conceptualised the problem of majority and minority, trapped in compulsory identities, that makes communalism the inevitable result?”

It is this inevitability of communal diatribe, of the lowest common denominators in politics that Indian politics need to rise above. This is being done, one comment at a time, as long as the Election Commission is watching. The bigger challenge lies beyond the results of 16 May, 2014.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society

In 2013, by way of abundant caution, Harper Collins India decided to pixellate a total of nine panels, including all the close-ups of penises in David Brown’s graphic novel “Paying for It.” While the content, in which Brown narrated his encounters with sex-workers, was left untouched, the publishers were wary of India’s laws against obscenity which make the depiction of nudity almost verboten. This is because a sheet of prudery covers any sexual expression and also governs the legal regulation of sexual speech.

Hence, many welcomed the Indian Supreme Court’s February 2014 ruling that merely because a picture showed nudity, it wouldn’t be caught within the obscenity net- “a picture can be deemed obscene only if it is lascivious, appeals to prurient interests and tends to deprave and corrupt those likely to read, see or hear it,” and having a redeeming social value would save it from being censored.

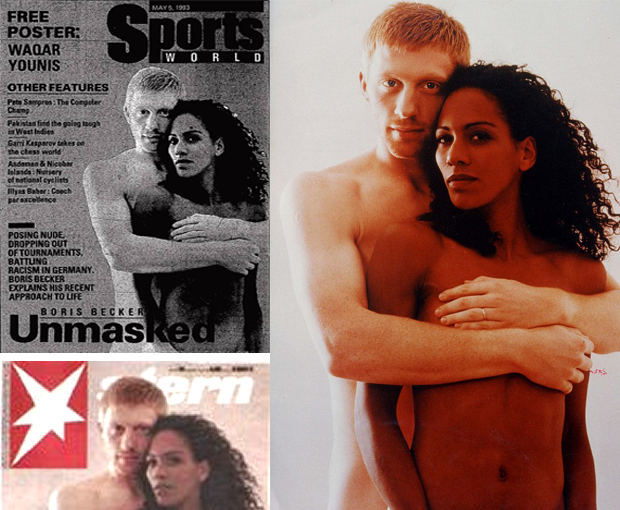

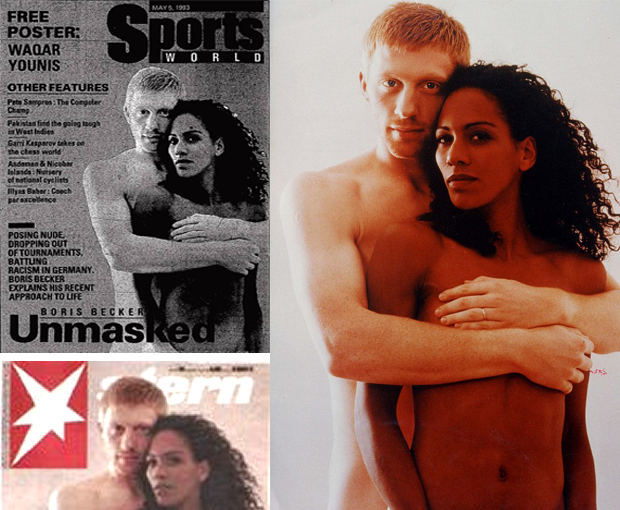

The decision came in an appeal filed in 1993. Sports World, a magazine published from Calcutta, had reproduced the photo on the cover of German magazine Stern. In that photograph, Boris Becker had posed nude with his then fiancée Barbara Feltus; it was his way of protesting against the racist abuse the couple were being subjected to. A solicitous lawyer dragged Sports World to court, alleging that the morals of society and young, impressionable minds were in jeopardy. He cited Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code which prohibits and penalises any form of expression tending towards prurience and encouraging depravity in the readers or viewers. The court rejected the contention, holding that the Hicklin’s Test for determining obscenity has become obsolete, besides imposing unreasonable fetters on the freedom of expression. This test, formulated by the House of Lords in 1868 in Regina v. Hicklin stipulated that ‘‘The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.’’

Instead, the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Roth – wherein “contemporary community standards” were held to be a far more reasonable arbiter, was directed to be adopted. The court also affirmatively cited the decision in Butler which, while upholding the test in Roth, added that anything which showed undue exploitation of sex or degrading treatment of women would remain prohibited.

While the Hicklin’s Test being jettisoned is a cause of relief, the judgement by no means can be held as finally freeing Indian law from the shackles of “comstockery.” George Bernard Shaw had coined this term in 1905 while raging against Anthony Comstock who had taken it upon himself to rid American society of vice. For Comstock, lust and sexual desire were abhorrent, and as he candidly proclaimed anything which even remotely arouses any sexual desire was to be dealt with in the most stringent manner. No wonder he had called Shaw an “Irish smut-peddler” in retaliation.

Gymnophobia, or the fear of nudity, isn’t something new to India’s Supreme Court. Also, it has always been female nudity and the fear of sexual desire which have governed the Court’s opinions. Its image-blaming position has repeatedly been used to reinforce the assumption that sexually explicit images trigger urges in men for which they cannot be held responsible. Depictions of nudity WERE condoned only if they achieved some “laudable social purpose” such as encouraging family planning or making people aware of caste-based atrocities. As Martha Nussbaum points out, collapsing the “disgust” for the nude female body with male sexual arousal and regarding sex as something furtive and impure results in the revulsion being projected on to the female body, thereby making the legal definition of obscenity collude with misogyny.

The present decision is no different. Because Feltus’ breasts were covered by Becker’s arm, and also because Feltus’ father was the photographer, it was held that only the most depraved mind would be aroused and titillated by the magazine cover. Most troubling of all is the overt reliance on contemporary community standards. True, that Indian society has evolved since 1993, but as Brenda Cossman details the scene in Canada in Butler’s aftermath, community standards became a rubric for majoritarian sexual hegemony, resulting in persecution and censorship by prudish vigilantes. And of course, it goes without saying that the search for “redeeming social value” usually ends at puritans’ doorsteps.

Comstockery’s tattered banner, emblazoned with “Morals, not art!” flies aflutter in India.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org