27 Aug 2014 | Asia and Pacific, India, News and features

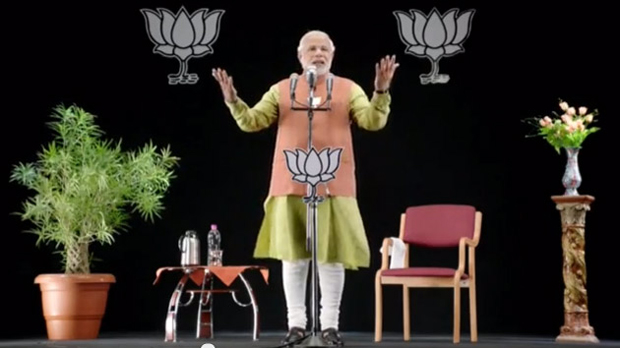

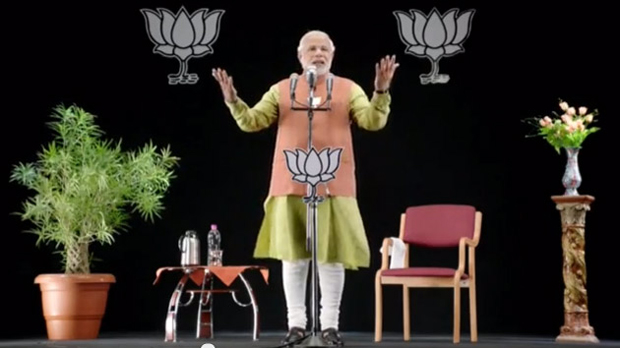

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Aug 2014 | Bulgaria, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Index on Censorship and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso are joining forces to map the state of media freedom in Europe. With your participation, we are mapping the violations, threats and limitations that European media professionals, bloggers and citizen journalists face everyday. We are also collecting feedback on what would support journalists in such situations. Help protect media freedom and democracy by contributing to this crowd-sourcing effort.

Bulgarian journalists covering the financial beat can breathe freely as the most controversial parts of the so-called “bank censorship” amendment to the criminal code have been removed by the legal committee of the national assembly.

In July, parliament adopted the amendment on first reading. The text of the draft outlined sentences of two to five years in prison for circulating “false or misleading information” about banks that could “cause panic”.

The amendment was suggested indirectly by the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) after a series of bank runs involving Bulgaria’s fourth largest credit institution, the Corporate Commercial Bank (CCB) and later an unrelated run involving financial institution the First Investment Bank (FIB).

It is still unclear who was behind these incidents. The run against CCB was likely caused by disagreements between media tycoon Delyan Peevski, one of the CCB’s large depositors and his old friend, Tsvetan Vasilev, the owner of CCB. Peevski started to remove funds, sparking a bank run which undermined the bank’s liquidity.

In the FIB case, three people have been arrested. They are suspected of spreading rumours about the imminent bankruptcy of FIB via emails and short text messages to the bank’s clients. This stirred mass panic, as people rushed to withdraw their money from the bank: in a few hours, BGN 800 million (£327 million) were withdrawn.

“Society is very sensitive especially to issues that affect the financial and banking stability as the memory of the banking crisis in 1996-1997 is still fresh,” said Petya Stoyanova, a financial and banking journalist from Bulgaria. During that crisis, 14 Bulgarian banks collapsed.

The memory of the mid-1990s financial crisis is the main reason behind the low public confidence in the Bulgarian banking system, which can easily be moved to panic. As a response, BNB proposed an amendment to the criminal code on 1 July stating that those who “disseminate misleading or untrue information on a bank or a financial institution that could create panic among the population, be punished with five to 10 years of imprisonment”.

BNB also proposed a fine ranging between BGN 5,000 and BGN 10,000 (£4,061) to be imposed in such cases. People causing significant damage or those having received significant illegal revenues through the aforementioned activities would be punished the same way.

According to Stoyanova, the proposals have been criticised by politicians and lawyers because of its vague language which, in a broad interpretation, could lead to a conviction for dissemination of any information related to the banking sector, even if it is not false or misleading.

After the first reading of the amendment in parliament, members of the legal committee applied a number of corrections. The revised amendment removes the danger of censorship by tightening up the language, which now refers to disseminating “false” banking information. While the potential fines for those spreading such information were increased, the possibility of prison has been eliminated.

The banking scandals hinted at the dimensions of backstage political machinations in Bulgaria. Stoyanova believes responsibility for malicious behaviour should have a place in future changes to the criminal code. Future lawmakers, she said, should not be allowed to quickly alter laws in violation of rules and best legislative practices, without public discussion.

The second reading of the amendment will be left to the next national assembly, as parliamentary elections will be held on 5 October.

More reports from Bulgaria via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Election law amendment could limit press freedom

Attacker sprays substance in Bulgarian sports journalist’s face

Bulgarian journalist beaten by football fans

Newspaper reporters attacked, threatened in Bulgaria’s city of Plovdiv

Arson Attack Against Bulgarian Journalist Genka Shikerova

This article was posted on 13 August 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Jul 2014 | Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, European Union, News and features, Statements

When Europe’s highest court ruled in May that individuals had a ‘right to be forgotten’ many were quick to hail this as a victory for privacy. ‘Private’ individuals would now be able to ask search engines to remove links to information they considered irrelevant or outmoded. In theory, this sounds appealing. Which one of us would not want to massage the way in which we are represented to the outside world? Certainly, anyone who has had malicious smears spread about them in false articles or embarrassing pictures posted of their teenage exploits, or even criminals whose convictions are spent and have the legal right to rehabilitation. In practice, though, the ruling was far too blunt, far too broad brush, and gave far too much power to the search engines to be effective.

At the time of the ECJ decision, Index warned that the woolly wording of the ruling – its failure to include clear checks and balances, or any form of proper oversight – presented a major risk. Private companies like Google – no matter how broad and noble their advisory board might be on this issue – should not be the final arbiters of what should and should not be available for people to find on the internet. It’s like the government devolving power to librarians to decide what books people can read (based on requests from the public) and then locking those books away. There’s no appeal mechanism, no transparency about how Google and others arrive at decisions about what to remove or not, and very little clarity on what classifies as ‘relevant’. Privacy campaigners argue that the ruling offers a public interest protection element (politicians and celebrities should not be able to request the right to be forgotten, for example), but – again – it is hugely over simplistic to argue that simply by excluding serving politicians and current stars from the request process that the public’s interest will be protected.

We are starting to see some of the (high profile) examples of how the ruling is being applied by Google. The Guardian’s James Ball reported on Wednesday that his newspaper had received an email notification from Google saying six Guardian articles had been scrubbed from search results.

“Three of the articles, dating from 2010, relate to a now-retired Scottish Premier League referee, Dougie McDonald, who was found to have lied about his reasons for granting a penalty in a Celtic v Dundee United match, the backlash to which prompted his resignation,” Ball wrote. “The other disappeared articles are a 2011 piece on French office workers making post-it art, a 2002 piece about a solicitor facing a fraud trial standing for a seat on the Law Society’s ruling body and an index of an entire week of pieces by Guardian media commentator Roy Greenslade.”

Similarly, the BBC was told that the link to a 2007 article by the BBC’s Economics Editor, Robert Peston, had also been removed.

Neither The Guardian nor the BBC has any form of appeal against the decision, nor were the organisations told why the decision was made or who requested the removals. You may argue – as some have done – that Google is deliberately selecting these stories (involving well-known journalists with large online followings) as a kind of non-compliant compliance to prove that the ruling is unworkable. Certainly, a fuller picture of the types of request, and much more detailed information about how decisions are arrived at, is essential. You can also point to the fact that it is easy to find the removed articles simply by going to a search engine’s domain outside Europe.

The fact remains that this ruling is deeply problematic, and needs to be challenged on many fronts. We need policymakers to recognise this flabby ruling needs to be tightened up fast with proper checks and balances – clear guidelines on what can and should be removed (not leaving it to Google and others to define their own standards of ‘relevance’), demands for transparency from search engines on who and how they make decisions, and an appeals process. If search engines really believe this is a poor ruling then they should make a clear stand against it by kicking all right to be forgotten requests to data protection authorities to make decisions. The flood of requests that would be driven to these already stretched national organisations might help to focus minds on how to prevent a ruling intended to protect personal privacy from becoming a blanket invitation to censorship.

This article was posted on 3 July 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements

The following is a transcript of a joint oral statement, led by ARTICLE 19 and supported by several IFEX members, that was read aloud today, 19 June 2014, at the 26th UN Human Rights Council session in Geneva:

Thank you Mr. President,

Two years ago this Council affirmed by consensus that “the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression”.

In 2014, the outcome document of Net-Mundial in Brazil recognised the vital role of the internet to achieve the full realisation of sustainable development goals. 31 UN Special Rapporteurs recently affirmed that guaranteeing the free-flow of information online ensures transparency and participation in decision-making, enhancing accountability and the effectiveness of development outcomes.

Development and social inclusion relies on the internet remaining a global resource, managed in the public interest as a democratic, free and pluralistic platform. States must promote and facilitate universal, equitable, affordable and high-quality Internet access for all people on the basis of human rights and net-neutrality, including during times of unrest.

The blocking of communications, such as the shutdown of social media in Malaysia, Turkey, and Venezuela is a violation of freedom of expression and must be condemned. Dissent online must be protected. We deplore the detention of Sombat Boonngamanong in Thailand, who faces up to 14 years imprisonment for using social media to urge peaceful resistance to the recent military coup in the form of a three-finger salute.

One year after the Snowden revelations, this Council must recognise that trust in the internet is conditional on respect for the rights to freedom of expression and privacy online, regardless of users’ nationality or location. Any mass (or dragnet) surveillance, which comprises collection, processing and interception of all forms of communication, is inherently disproportionate and a violation of fundamental human rights.

The targeted interception and collection of personal data must be conducted in accordance with international human rights law, as set out in the necessary and proportionate principles. Critical and intermediate infrastructure must not be tampered with for this end, nor should any system, protocol or standard be weakened to facilitate interception or decryption of data.

ARTICLE 19 urges the Human Rights Council to take action to comprehensively address these challenges.

Thank you.

Signed,

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

ARTICLE 19

Association of Caribbean Media Workers

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

Freedom Forum

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Press Institute

Maharat Foundation

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

National Union of Somali Journalists

Norwegian PEN

Pacific Islands News Association

Pakistan Press Foundation

PEN Canada

Privacy International

Reporters Without Borders

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

West African Journalists Association

World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters – AMARC

Access

Alternative Informatics

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

Bangladesh Internet Governance Forum

Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and Communications (BNNRC)

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House

Big Brother Watch

Bir Duino (Kyrgyzstan)

Bits of Freedom

Bolo Bhi Pakistan

Bytes For All

Center for e-parliament Research

Centre for Internet & Society

Center for National and International Studies, Azerbaijan

Center for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights, Russia

Chaos Computer Club

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

Digital Rights Foundation, Pakistan

Electronic Privacy Information Center

English Pen

European Centre for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL)

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor

Human Rights Monitoring Institute, Lithuania

International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL)

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Kenya Human Rights Commission

Liberty

OpenMedia.org

Open Net Korea

Open Rights Group

Panos Institute West Africa

Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy & Public Interest Clinic (CIPPIC)

Simon Davies, publisher of “Privacy Surgeon”

Thai Netizen Network

Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum