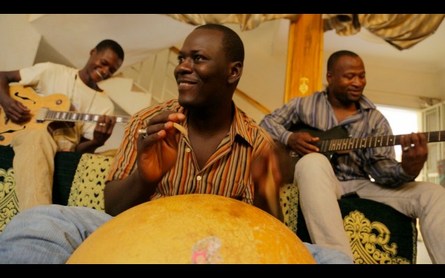

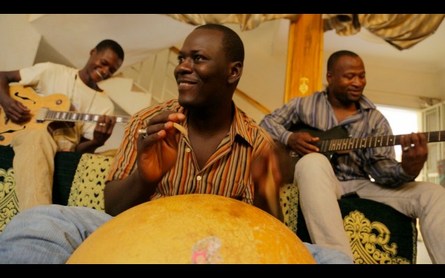

17 Apr 2014 | Events

Like many other musicians in Mali, Tinawiren were forced into exile by a blanket ban on all music (including mobile ringtones) introduced when hard line Islamists took control of the country in 2012. Tensions continue and award-winning Johanna Schwartz has been capturing this tale in her latest documentary ‘They Will Have To Kill Us First’.

Join us for a preview of this documentary and schedules permitting, a live link up with Manny Ansar – director of the Festival au Desert and central in making the situation for musicians in Mali known to the world.

Subsequently, we’ll explore artistic freedom from a global and local standpoint with renowned writer and broadcaster Kenan Malik, Belfast based international artist Sinead O’Donnell (just back from China) and Julia Farrington of Index.

When: Saturday 3rd may, 15:30-17:00

Where: Belfast Exposed, Donegall St – part of Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival

Tickets: Free – Reserve Your Place Here

#CQAF14

16 Apr 2014 | Australia, News and features, Politics and Society

Australian prime minister Tony Abbott

In weeks where Prime Minister Tony Abbott of Australia has publicly praised the importance of freedom of speech in relation to the repeal of a section of the Racial Discrimination Act (18C) it might seem strange that civil servants caught criticising the government, or PM, can be sanctioned for illicit social media use. But to look at the two and suggest it implies gross, implicit hypocrisy, as some have, is not the most nuanced interpretation; however, the new policy code, which actually only applies to one government department bears looking at.

The new guidelines, Social Media Policy of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, outline what can and cannot be done on social media by employees and seem at pains to cover all bases while also being remarkably intrusive compared with other similar government documents.

The guidelines state they are aimed at ensuring the public believes in the impartiality of those in the Department of the PM&C. They govern social media use, including anonymous comments, during office hours and outside of work, on private devices. What has been noted by the media however is that anonymous speech may be sanctioned and employees are requested to “dob” — that is, report — on colleagues if they see them contravening the new policy. Staff can be reported for being “critical or highly critical of the Department, the Minister or the Prime Minister’’ or “so harsh or extreme in their criticism of the government, government policies, a member of parliament from another political party, or their respective policies, that they could raise questions about the employee’s capacity to work professionally, efficiently or impartially”.

Despite the leaked document now available online, the department maintains, according to the Canberra Times, that its policy on public social media use is a strictly internal document and will not comment. The department also states that no person should speak directly with the media but rather refer all queries to the media department, where the scribe can address queries in writing. This bureaucratic attempt at transparency or a “timely response” is neither limited to this department or government. Under the previous Labor government certain departments, such as the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, took much the same stance at times. Of course, now even refugee or boat arrival numbers are kept secret and weekly press conferences have been scrapped.

The policy has been defended by Freedom Commissioner Tim Wilson, who also defends the repeal of 18C in the name of freedom of speech. He told the Canberra Times: “As I read it, the current policy allows public servants to be critical of government policy, but requires that they do so in a way that does not compromise their capacity, or perception, that they will exercise their role as a public servant in an impartial way.” Wilson believes in the civilising power of codes of conduct and that such “voluntary” agreements do not undermine essential freedom of speech.

The document has rather broad-ranging edicts which could be open to interpretation. It is understood people may “participate robustly” in debate, but robustness may not trump impartiality or professionalism. It is useful then that Abbott’s daughter does not now work for the prime minister’s department. After publicly calling him a “lame, gay, churchy loser” in 2009 her impartiality could be questionable.

This article was published on April 16, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Apr 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Protesters gathered outside a Stop Porn Culture conference in March 2014 organised by Gail Dines. Protesters included porn stars, filmmakers, artists, sex workers and supporters who believe in freedom of expression. (Photo: Rachel Megawhat/Demotix)

Last year London Mayor Boris Johnson’s aide, Simon Walsh, was arrested for possession of extreme pornography: depictions of anal fisting and urethral sounding. The respected barrister’ very public prosecution tore his life apart and lost him his jobs. In just 90 minutes the jury threw out his case – Walsh’s images were safe and legally produced.

The law under which he was prosecuted (Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008) was intended to affect only 30 people per year, but over 1,300 were prosecuted in 2012/13 alone. Clarification of what should be classed as “extreme”, promised by the Lords, never materialised. Government lawyers have attacked a wide range of materials, many of which juries consider innocent.

Now the government is sneaking through a vast extension to pornographic prohibition. It’s so vaguely worded that it could cover 50 Shades of Grey (if filmed), Game of Thrones or Florentine statues. Those found guilty of possession could face 3 years in prison and an unlimited fine.

Under the cloud of Cameron’s anti-child abuse crusade, possessing explicit/realistic portrayals of “the non-consensual penetration of a person’s vagina, anus or mouth by another,” real or simulated, will be illegal. The rhetoric that launched Claire Perry’s disastrous internet filtering initiative – the one that blocks abuse support, sex education and suicide helpline websites – also mandated this law. That rhetoric displays utterly muddled thinking, a confusion between stopping child abuse, stopping children accessing adult material and stopping anyone accessing non-mainstream material.

The change’s motivation is laudable. Genuine rape or abuse depictions (i.e. filming real crimes) should be illegal, all agree. Some women’s groups argue exposure to violent pornography affects viewers’ behaviour- RASASC calls the move a “step forward in preventing rapists using rape pornography to legitimise and strategise their crime”.

However, campaigners contend the draft law’s language is too ambiguous. A policy researcher from anti-censorship organisation Backlash argues: “The law will cover much more than the legislators imagine or intend.” Passing this law as an appendage in a “bumper bill (that includes) lots of legitimate concerns – a radical overhaul of probation and legal aid – (means this) very delicate matter isn’t getting appropriate democratic oversight”.

The government’s strategy, using child pornography as a blanket justification, makes effective opposition or refinement impossible. No politician spoke against the amendment in the bill’s readings or committee stage. Which MP, mindful of re-election, would stand for the right to possess violent erotica? Labour support the provision uncritically, denying it appropriate scrutiny.

Such a serious proscription, which might endanger harmless women and men, merits its own public debate, not back-door legislation. Solicitor Myles ‘ObscenityLawyer’ Jackman, who represented Walsh, highlights the dangerous subjectivity of judging pornography “realistic”, plus the “absence of any evidence proving…a causal link” between such material and Cameron’s “normalise(d) sexual violence against women”. A representative survey of 19,000 UK adults cited by three academics shows 1/3 of adult fantasies include domination or submission, and about 5% of Britons fantasise about delivering/experiencing violence. These academics’ parliamentary evidence repeated Jackman’s scepticism of the link between pornography and real-world crime. Groups like Rape Crisis South London and the End Violence Against Women Coalition assert such pornography does promote dangerous beliefs. The government itself “believes such images are unacceptable and most people would regard them as disgusting and deeply disturbing,” implying the majority’s moral distaste is grounds for legislation.

Groups like Sex & Censorship and Backlash protest the bill’s wording and justification, arguing millions of law-abiding kink practitioners might be criminalised for depicting safe, consensual, private acts. Sexual minorities including the LGBT community, bondage enthusiasts, horror-movie recreators and “vampire and goth enthusiasts who use fake blood in roleplay” could be covered, Backlash told me. Even Rackley and McGlynn, the Durham University academics who championed this law for years, criticise the bill’s wording, demanding clarification specifically banning “realistic images”, protection for “private depictions of consensual BDSM activity” and consideration of context.

Sex-positive feminism raises questions over what the bill would achieve. Arguments that violent pornography (and general sexual imagery) warps childhood development, perpetuates objectification and enables rape culture are valid, but attacking one subsection of pornography won’t stop children seeing questionable images. They fill celebrity magazines, tabloids, advertising and primetime TV.

In terms of child protection, then, this may be window-dressing. It’s far more important for schools to promote effective sex education covering consent, gender, identity and relationships, rather than a “see no evil” approach. Such education is woefully lacking and outdated. Meanwhile the government has cut funding for sexual health services for vulnerable teens and youth services, and is attacking endangered women’s panic rooms via the “bedroom tax”.

The government may be simultaneously attacking the harmless, and harming those who are helpless. The extension of extreme pornography censorship is dangerous because it’s had minimal public discussion, the wording is poorly considered, and it’s unlikely to address the problem used to promote it.

This article was published on April 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Apr 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News and features, North Korea

A view into South Korea from North Korea (Image: Johannes Barre/iGEL/Wikimedia Commons)

North Korea hit global headlines again last week. This was in part because of the UN resolution condemning the catastrophic, ongoing abuses against its people, in the wake of a 400-page report chronicling the country’s countless human rights violations. However, as much attention, if not more, was devoted to the curious case of state-imposed hairstyles. Again it seemed the world’s focus was fixed on the bizarre end of the spectrum of outrageous stories coming out of the hermit kingdom. But while reports of haircuts, hysterical grieving masses, Dennis Rodman and killer dogs — true or not — have spread like wildfire across social media, Kim Young-Il has gone about his work of fighting for the often forgotten rights of North Korean defectors.

Kim escaped North Korea himself in 1996. Forced to join the army as a teenager, he soon discovered that the military, like the rest of the country, suffered from malnourishment. North Korea experienced devastating famine throughout the 1990s, in no small part down to mismanagement by authorities. Together with his parents, he made the gruelling journey to China, where they stayed for four-and-a-half years as illegal immigrants. “I had every job you can imagine,” he says. Finally, tired of living in constant fear of deportation, they made their way to South Korea. Kim went to university, where he says frequent questions from fellow students writing on North Korea, made him think about his heritage. After graduating he set up the non-governmental organisation PSCORE to help those who, like he did, make the difficult decision to escape.

The risks of defecting are huge. Many are put off even trying by widespread rumours backed up by state propaganda, of defectors being interrogated and killed by South Korean authorities. The country’s near complete lack of freedom of expression makes such stories difficult to debunk. Simply getting out of North Korea is no guarantee of freedom either. Many defectors have to go through China, the regime’s powerful ally, which operates a strict returns policy for defectors. Returnees face a multitude of possible punishments, from forced labour to execution. “If China changes their stance, that wholly changes the situation,” Kim says. At present, however, there is little to suggest they will. For those managing to avoid return, the threat to family left behind looms large. Kim’s sister-in-law is a political prisoner today for speaking on the phone to his wife.

Kim’s reasoning was that he’d rather face these dangers than the prospect of starving to death in his home country. It appears many agree. Nobody knows the exact number of defectors, as many keep quiet about it due to dangers posed to loved ones. What is certain is that it has shot up because of the devastating effects of the famine. This has also changed the demographic of defectors. While it used to be an option utilised mainly by relatively high-level North Koreans, today people from all sections of society are making big sacrifices in hope of a better life abroad.

Part of the reason could also be that in the some 60 years since its establishment, life in the Democratic Republic has shown no signs of improving. Kim tells of a complex and rigid class system, explaining that records of your grandparents’ position and occupation are used to determine your standing in society. The state decides who can be a doctor and who can be a farmer. Women have some possibilities for upward social mobility through marriage, but on the whole, your path in life is determined almost entirely by factors outside your control. That is, with one notable exception: “It’s difficult to move up, but very simple to drop down.”

This system, reassuring many North Koreans that there is always someone worse off than you, has played its part in deterring popular dissent and large-scale social uprising, Kim explains. That, and the crippling fear of a brutal regime acting with impunity. Asked whether any noticeable changes came with the change of leader, Kim said that any hope of the country opening up when Kim Jong-un took power following the death of his father, was quickly extinguished. The issue of South Korean pop culture is striking example. Kim Jong-un and his family are big consumers of their neighbours’ booming entertainment industry, while the official line is that it’s strictly prohibited. Kim says a man as recently found to be selling CDs with South Korean films and music. He was publicly executed to set an example for others.

So many head for China and hope. In China is where PSCORE’s work starts. Kim travels over several times a year to meet defectors and bring them to South Korea. Finding them isn’t always easy, and when he does, many are afraid to speak. “We don’t ask questions immediately. We try to identify with them first,” he explains, mindful of the rumours and propaganda they have been subjected to in the north. Many have gruelling journeys behind them. Nam Bada, PSCORE’s General Secretary, showed Index pictures of a girl’s feet, disfigured by frostbite. She lost her shoes travelling on foot in the snow. Others have used brokers; locals living in the border areas, charging to help defectors cross. The brokers are “just interested in profit, not human rights” says Kim, and estimates the price is currently between $2000-6000. The practise puts defectors, especially female ones, at risk of human trafficking. PSCORE have helped a number of women from being sold by brokers.

Once they reach South Korea, they’re interrogated by authorities. “90% of South Korea’s information about North Korea comes from defectors,” Kim explains. After that, they’re enrolled in a basic, three-month education programme, and then more or less left to their own devices. The transition from arguably the most closed society in the world, to one of the most open ones can be difficult. Kim highlight language as a big hurdle. North Korean has been completely shielded from outside influence for decades, while South Korean has been free to develop. And while there is no discrimination against defectors legally and on paper, Kim says they are often discriminated against.

It’s against this backdrop PSCORE are providing education to defectors and helping them adjust to their new lives. Kim compares the process to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: “At first, people are just glad to be fed, but later they want more.” They also continue to campaign against North Korean human rights violations, which the aforementioned UN report described as “systematic, widespread and gross” and in many instances constituting crimes against humanity. Something to keep in mind the next time North Korea is in the news because of haircuts.

Support PSCORE’s work here

This article was posted on April 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org