4 Jun 2021 | Belarus, China, Hong Kong, News and features

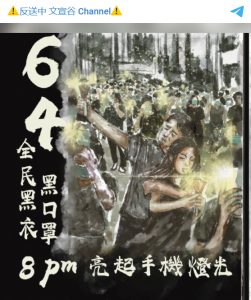

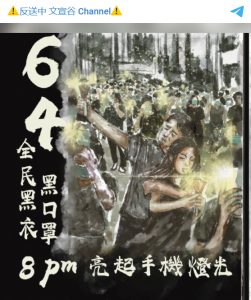

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

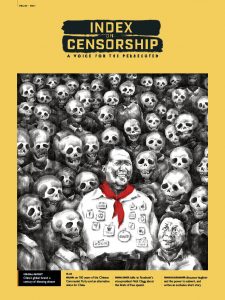

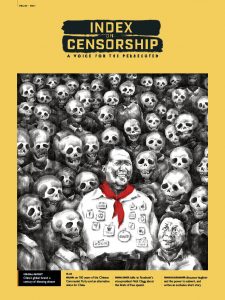

28 Apr 2021 | Africa, Burma, China, Hong Kong, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, United States, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021 extras

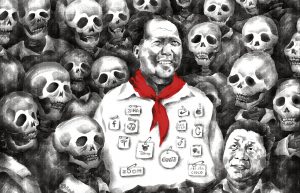

Illustration: Badiucao

Index looks back on 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and how their censorship laws continue to shape the lives of people around the world and threaten their right to free speech. Inside this edition are articles by exiled writer Ma Jian and an interview with Facebook’s vice-president for global affairs, former UK deputy Prime minister Nick Clegg; as well as an exclusive short story from acclaimed writer Shalom Auslander.

Acting editor Martin Bright said: “I am delighted to introduce the latest edition of Index which marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the magazine and I am proud that we are continuing the founders’ legacy of opposition to totalitarianism.”

“In this Spring edition of Index we are particularly pleased to publish an exclusive essay by the celebrated Chinese writer Ma Jian, who suggests that an alternative tradition of tolerance and freedom is still possible.”

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Fighting back against the menace of Slapps by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Governments continue to threaten journalists with vexatious law suits to stop critical reporting

Friendless Facebook by Sarah Sands: An interview with Facebook vice-president Nick Clegg about being a British liberal at the heart of the US tech giant

Standing up to a global giant by Steven Donziger: A lawyer who has gone head to head with the oil industry since 1993 at great personal cost tells his story

Fear and loathing in Belarus by Yahuen Merkis and Larysa Shchryakova: The crackdown on journalism has continued with arrests. Read the testimony of two reporters

Killed by the truth by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Babar Qadri was one of Kashmir’s most strident voices, until he was gunned down in his garden

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: Arguments about the removal of statues cause a stir

The martial art of free speech by Ari Deller and Laura Janner-Klausner: The question of Cancel Culture continues to rage. Is it really a problem?

Ma Jian

Burning through censorship: Censorship-busting online organisation GreatFire celebrates its 10th anniversary

The party is your idol by Tianyu M. Fang: China’s propaganda is adapting to target young people

Past imperfect by Rachael Jolley: Four historians explain how the CCP shaped China and ask if globalisation will be its undoing

Turkey changes its tune by Kaya Genç: Uighur refugees living in Turkey find themselves victims of a change in foreign policy

The human face and the boot by Ma Jian: The acclaimed writer-in-exile reflects on 100 years of the CCP and its legacy of bloodshed

A moral hazard by Sally Gimson: Universities around the world and the CCP’s challenges to academic freedom

Director’s cuts by Chris Yeung: Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK has been squeezed by China’s tightening control

Beijing buys Africa’s silence by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Africa’s rich natural resources are being hoovered up by China

A new world order by Natasha Joseph: Journalist Azad Essa found when he wrote about China in Africa, his writing was silenced

A most unlikely ally by Stefan Pozzebon: Paraguay has long been an ally of Taiwan, but it’s paying an economic price

China’s artful dissident: A profile of our cover artist: the exiled cartoonist Badiucao.

Lies, damned lies and fake news by Nick Anstead: Fake news is rife, rampant and harmful. And we can only counter it by making sure that the truth is heard

Censorship? Hardly by Clive Priddle: Even the most controversial book usually finds a publisher after it has been turned down

A voice for the persecuted by Ruth Smeeth: As Index celebrates its 50 year anniversary, we note why free speech is still important

Collective ©ALEXANDER NANAU PRODUCTION

Don’t joke about Jesus by Shalom Auslander: An exclusive short story based on a joke by the acclaimed author of Mother for Dinner

Poet who haunts Ukraine by Steve Komarnyckyj: Vasyl Stus, the writer who remains a Ukrainian hero, 35 years after perishing in a Soviet gulag

The freedom of exile by Khaled Alesmael, Leah Cross: A young refugee Syrian writer on the love between Arab men

Forbidden love songs by Benjamin Lynch: Iran’s underground pop music scene upsets the regime

Reviews: Saudi Arabia’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi, USA Gymnastics and healthcare in Romania: we review three new documentaries

War of the airwaves by Ian Burrell: The Chinese government faces difficulties with its propaganda network CGTN

16 Apr 2021 | Fellowship 2021, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, a 2020 Freedom of Expression Awards winner

This week we were interviewing for a new member of the team to help support our work on the Freedom of Expression awards. The joy of interviewing for a new role is that it makes you reflect on what you do and why, even as you’re speaking to the candidates. As I was outlining the importance of the awards, I was reminded of why they are so incredibly important and not just for the winners, but also for the team. The fact is they give us hope, we get to show real solidarity with people who are on the frontline, people who every day are demanding their rights and protections under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Those people shortlisted for an award are typically unknown outside their countries, their stories untold. They have been jailed for campaigning for free speech. Hounded for using their talents as artists and writers to explore people’s realities under totalitarian regimes. Threatened for being journalists exposing corruption and repression at a national level. They are also just people who have found themselves in horrendous situations which they are determined to help fix.

Our award-winners and all of those nominated are extraordinary. They are inspirational. And they honestly keep the team going when day in and day out we are exposed to some of the horrors of what people are facing in too many places around the world, from Myanmar to Kashmir, from Afghanistan to Hong Kong, from Belarus to Xinjiang, from Komsomolsk-on-Amur to Greece.

It can be emotionally exhausting just trying to keep on top of what is happening in too many countries by too many authoritarian leaders. Soul-destroying to say today we have to focus on Egypt rather than Iran because we don’t have enough resource. The guilt that we aren’t doing enough or that we aren’t providing enough support or that the world has moved on and we can’t get traction for someone’s story. The world can just feel too depressing.

The Index team is extraordinary and resilient – but we all need a little hope.

And that’s what our awards do – they provide hope. The remind us of the struggles that people are prepared to fight and allow us to celebrate those people are fighting the good fight – so they know they are not alone, and that people genuinely care what happens to them.

Our award nominees and the eventual winners are extraordinary individuals but for the team at Index they embody our mission – to ensure that we are a Voice for the Persecuted. They represent the best of us, and we honour and support them not just because of who they are and what they have done – but because of what they represent. Bravery, resilience and determination for a better world.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.