24 Apr 2014 | India, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

“Gas Wars — Crony Capitalism and the Ambanis” is journalists Paranjay Guha Thakurta, Subir Ghosh and Jyotirmoy Chaudhuri’s collaborative effort exposing one of India’s biggest business conglomerates’ murky dealings with the government.

The authors detail how a hydrocarbon production sharing contract in Krishna Godavari, off the Bay of Bengal, in Andhra Pradesh, was allegedly rigged to benefit Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) headed by Mukesh Ambani, at significant cost to the public exchequer. The book contends that high ranking government officials, including ministers, aided and abetted the pillage of public resources.

A fire-and-brimstone attorney’s notice from RIL arrived the day after the book was launched. It had quite an eerie feel to it. The notice started with a disclaimer about the Reliance groups’ highest regards for constitutional rights including freedom of expression, and then accused the authors of a deep-rooted conspiracy to malign the company’s reputation. It took strong exception to the book’s title and went on to allege that the contents are nothing but malicious canards. Nothing sort of an unconditional public apology would mitigate the harm caused, failing which, criminal and civil proceedings would be unleashed. Drawing lessons from the Wendy Doniger episode, the notice threw out a wide net. It included not only Authors Upfront and FEEl Books Private Ltd, the e-book publisher and distributors, but also “electronic distributors” like Flipkart and Amazon.in. Even the Foundation for Media Professionals, a non-governmental organisation which forwarded e-invites for the launch event, was not spared. A second notice in the same vein, this time from RNRL, followed soon after.

Why does the book roil the Ambanis? In an interview, Guha Thakurta, one of the authors, revealed that the book delves into how both the central and the Gujarat governments worked hand-in-glove with the Reliance companies in structuring the deal. In effect, the government kowtowed to the companies’ diktats, the authors assert. It went out on a limb to hike the price of gas, and was stopped in its tracks by the Election Commission.

Moreover, it has become a hot-button political issue since the Aam Aadmi Party, which is contesting the elections on an anti-corruption plank, has left no stone unturned to relentlessly question the Ambanis and Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi, who is running for prime minister. The questions have so unsettled the Reliance companies that they have taken to an “Izzat (honour) campaign” and SMS blitz to convince Indians of its innocence. Further, the companies claim in court that they are victims of a “honey trap”- apparently the government isn’t the custodian of the country’s natural resources and had lured them with false promises.

Guha Thakurta maintains that he has acted in the finest traditions of fairness and journalistic integrity. Senior officials of the companies have been interviewed, their views, refutations and assertions–everything has been presented. But his travails in publishing the book provide cause for consternation. Self-publication was the sole option, if one goes by Bloomsbury India‘s craven surrender. For the record, not only did it withdraw a book which would have exposed how India’s national airline was bled dry, but went ahead and apologised to the minister who threatened to sue for libel. A leading national publisher had been approached, and a deal had been worked out, but Guha Thakurta decided to go solo when substantial changes were demanded.

For Reliance, intimidating anyone who isn’t writing hagiographies of Dhirubhai Ambani–the company’s founder–is par for the course; one is a worse offender for even whispering anything against their cavorting with officials in the top echelons of government. And their modus operandi of silencing criticism reveals the extent of crony capitalism.

In its May 2013 issue, Caravan magazine published a cover story on India’s Attorney General. It bared details about how his opinions to the government were tailored to help the Ambanis wiggle out of an investigation into a graft scandal. Interestingly, three legal notices, each more threatening than the other, reached the magazine in the month of April, demanding complete silence. Caravan took them head on, but not every publisher would have the wherewithal to resist impending SLAPP suits.

The threats to Caravan were benign if compared with what the Ambanis did to “The Polyester Prince”, Hamish McDonald’s 1998 biography of Dhirubhai. The plight of that book is a true testament to the Ambanis’ power of insidious censorship. Incessant threats of injunctions from every high court in India ensured that the book quietly vanished off the shelves.

And why not? McDonald had quoted him — “I don’t break laws, I make laws.”

UPDATE:

If there were any doubts as to the extent of Reliance Industries’ determination to suppress the tiniest whisper of criticism, they are dispelled by the latest fusillade hurled against the authors. This comes in the form of a couple of fresh legal notices laden with preposterous claims and egregious threats.

The first one, dated 22 April, cherrypicks random, disjointed passages from the book to make out a case for libel. Suffice it to say, even prima facie innocuous statements have been included.

Dated 23 April, the second one accuses the authors of malevolent mendacity in publishing and publicising their “pamphlet” (yes, that’s the term used to substantiate the charges of the book being a piece of malicious propaganda), and goes on to claim that even the launch event was designed to malign the companies.

At that event, Guha Thakurta had quoted former Governor of West Bengal Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s statement that “Reliance was a parallel state, brazenly exercising total control over the country’s resources”. But Reliance hasn’t trained its guns on Gandhi; instead it accuses the author of slander. It is not pusillanimity but very sound legal strategy — the modus operandi of SLAPP suits, which the company adopts because taking on Gandhi, a widely respected and renowned public figure, would backfire.

Playing both judge and jury, Reliance determines that a sum of INR 100 crore (10 billion) as “token damages”, to be paid within ten days, would be just restitution. Never before has any plaintiff arrogated to itself such a right even before going to court.

The next claim is much more sinister. The authors are directed to remove all traces of “publicity material” — both in print and on the internet, including the website http://www.gaswars.in/. This patently means that even this particular report has to be taken off. Since when have two corporations been so imperious as to stake claim to sovereignty over the internet?

An earlier version of this article identified the basin in question in the production sharing contract as one Kasturba Gandhi in Gujarat, when it should be Krishna Godavari, off the Bay of Bengal, in Andhra Pradesh. An earlier version also stated that both Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) headed by Mukesh Ambani, and Reliance Natural Resources Limited (RNRL) headed by Anil Ambani, were involved in the sharing contract, when it should only be RIL. This has been corrected.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 2014 | Magazine, Politics and Society

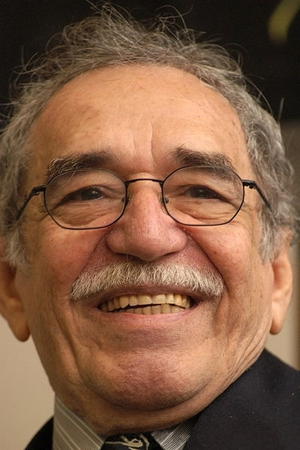

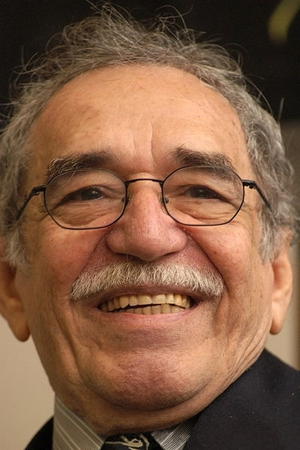

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

The newspaper was then divided into three large departments: news, features and editorial. The most prestigious and sensitive was the editorial department; a reporter was at the bottom of the heap, somewhere between an intern and a gopher. Time and the profession itself has proved that the nerve centre of journalism functions the other way. At the age of 19 I began a career as an editorial writer and slowly climbed the career ladder through hard work to the top position of cub reporter.

Then came schools of journalism and the arrival of technology. The graduates from the former arrived with little knowledge of grammar and syntax, difficulty in understanding concepts of any complexity and a dangerous misunderstanding of the profession in which the importance of a “scoop” at any price overrode all ethical considerations.

The profession, it seems, did not evolve as quickly as its instruments of work. Journalists were lost in a labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control. In other words: the newspaper business has involved itself in furious competition for material modernisation, leaving behind the training of its foot soldiers, the reporters, and abandoning the old mechanisms of participation that strengthened the professional spirit. Newsrooms have become a sceptic laboratories for solitary travellers, where it seems easier to communicate with extraterrestrial phenomena than with readers’ hearts. The dehumanisation is galloping.

Before the teletype and the telex were invented, a man with a vocation for martyrdom would monitor the radio, capturing from the air the news of the world from what seemed little more than extraterrestrial whistles. A well-informed writer would piece the fragments together, adding background and other relevant details as if reconstructing the skeleton of a dinosaur from a single vertebra. Only editorialising was forbidden, because that was the sacred right of the newspaper’s publisher, whose editorials, everyone assumed, were written by him, even if they weren’t, and were always written in impenetrable and labyrinthine prose, which, so history relates, were then unravelled by the publisher’s personal typesetter often hired for that express purpose.

Today fact and opinion have become entangled: there is comment in news reporting; the editorial is enriched with facts. The end product is none the better for it and never before has the profession been more dangerous. Unwitting or deliberate mistakes, malign manipulations and poisonous distortions can turn a news item into a dangerous weapon.

Quotes from “informed sources” or “government officials” who ask to remain anonymous, or by observers who know everything and whom nobody knows, cover up all manner of violations that go unpunished.But the guilty party holds on to his right not to reveal his source, without asking himself whether he is a gullible tool of the source,manipulated into passing on the information in the form chosen by his source. I believe bad journalists cherish their source as their own life – especially if it is an official source – endow it with a mythical quality, protect it, nurture it and ultimately develop a dangerous complicity with it that leads them to reject the need for a second source.

At the risk of becoming anecdotal, I believe that another guilty party in this drama is the tape recorder. Before it was invented, the job was done well with only three elements ofwork: the notebook,foolproof ethics and a pair of ears with which we reporters listened to what the sources were telling us. The professional and ethical manual for the tape recorder has not been invented yet. Somebody needs to teach young reporters that the recorder is not a substitute for the memory, but a simple evolved version of the serviceable, old-fashioned notebook.

The tape recorder listens, repeats – like a digital parrot – but it does not think; it is loyal, but it does not have a heart; and, in the end, the literal version it will have captured will never be as trustworthy as that kept by the journalist who pays attention to the real words of the interlocutor and, at the same time, evaluates and qualifies them from his knowledge and experience.

The tape recorder is entirely to blame for the undue importance now attached to the interview. Given the nature of radio and television, it is only to be expected that it became their mainstay. Now even the print media seems to share the erroneous idea that the voice of truth is not that of the journalist but of the interviewee. Maybe the solution is to return to the lowly little notebook so the journalist can edit intelligently as he listens, and relegate the tape recorder to its real role as invaluable witness.

It is some comfort to believe that ethical transgressions and other problems that degrade and embarrass today’s journalism are not always the result of immorality, but also stem from the lack of professional skill. Perhaps the misfortune of schools of journalism is that while they do teach some useful tricks of the trade, they teach little about the profession itself. Any training in schools of journalism must be based on three fundamental principles: first and foremost, there must be aptitude and talent; then the knowledge that “investigative” journalism is not something special, but that all journalism must, by definition, be investigative; and, third, the awareness that ethics are not merely an occasional condition of the trade, but an integral part, as essentially a part of each other as the buzz and the horsefly.

The final objective of any journalism school should, nevertheless, be to return to basic training on the job and to restore journalism to its original public service function; to reinvent those passionate daily 5pm informal coffee-break seminars of the old newspaper office.

Index on Censorship magazine is proud to have had Gabriel García Marquez among its contributors – a long list which has also included Samuel Beckett, Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie and many other literary greats. Printed quarterly, the magazine mixes long-form journalism with short stories and extracts from plays – some of which have been banned or censored around the world. Subscribe here

17 Apr 2014 | Events

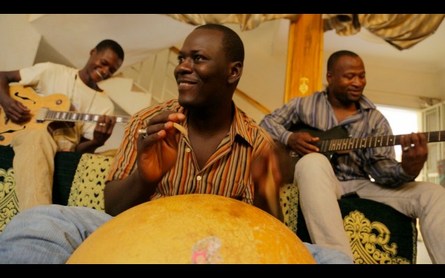

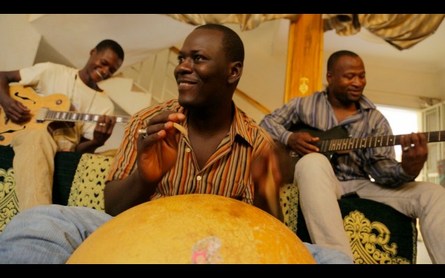

Like many other musicians in Mali, Tinawiren were forced into exile by a blanket ban on all music (including mobile ringtones) introduced when hard line Islamists took control of the country in 2012. Tensions continue and award-winning Johanna Schwartz has been capturing this tale in her latest documentary ‘They Will Have To Kill Us First’.

Join us for a preview of this documentary and schedules permitting, a live link up with Manny Ansar – director of the Festival au Desert and central in making the situation for musicians in Mali known to the world.

Subsequently, we’ll explore artistic freedom from a global and local standpoint with renowned writer and broadcaster Kenan Malik, Belfast based international artist Sinead O’Donnell (just back from China) and Julia Farrington of Index.

When: Saturday 3rd may, 15:30-17:00

Where: Belfast Exposed, Donegall St – part of Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival

Tickets: Free – Reserve Your Place Here

#CQAF14

11 Apr 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Protesters gathered outside a Stop Porn Culture conference in March 2014 organised by Gail Dines. Protesters included porn stars, filmmakers, artists, sex workers and supporters who believe in freedom of expression. (Photo: Rachel Megawhat/Demotix)

Last year London Mayor Boris Johnson’s aide, Simon Walsh, was arrested for possession of extreme pornography: depictions of anal fisting and urethral sounding. The respected barrister’ very public prosecution tore his life apart and lost him his jobs. In just 90 minutes the jury threw out his case – Walsh’s images were safe and legally produced.

The law under which he was prosecuted (Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008) was intended to affect only 30 people per year, but over 1,300 were prosecuted in 2012/13 alone. Clarification of what should be classed as “extreme”, promised by the Lords, never materialised. Government lawyers have attacked a wide range of materials, many of which juries consider innocent.

Now the government is sneaking through a vast extension to pornographic prohibition. It’s so vaguely worded that it could cover 50 Shades of Grey (if filmed), Game of Thrones or Florentine statues. Those found guilty of possession could face 3 years in prison and an unlimited fine.

Under the cloud of Cameron’s anti-child abuse crusade, possessing explicit/realistic portrayals of “the non-consensual penetration of a person’s vagina, anus or mouth by another,” real or simulated, will be illegal. The rhetoric that launched Claire Perry’s disastrous internet filtering initiative – the one that blocks abuse support, sex education and suicide helpline websites – also mandated this law. That rhetoric displays utterly muddled thinking, a confusion between stopping child abuse, stopping children accessing adult material and stopping anyone accessing non-mainstream material.

The change’s motivation is laudable. Genuine rape or abuse depictions (i.e. filming real crimes) should be illegal, all agree. Some women’s groups argue exposure to violent pornography affects viewers’ behaviour- RASASC calls the move a “step forward in preventing rapists using rape pornography to legitimise and strategise their crime”.

However, campaigners contend the draft law’s language is too ambiguous. A policy researcher from anti-censorship organisation Backlash argues: “The law will cover much more than the legislators imagine or intend.” Passing this law as an appendage in a “bumper bill (that includes) lots of legitimate concerns – a radical overhaul of probation and legal aid – (means this) very delicate matter isn’t getting appropriate democratic oversight”.

The government’s strategy, using child pornography as a blanket justification, makes effective opposition or refinement impossible. No politician spoke against the amendment in the bill’s readings or committee stage. Which MP, mindful of re-election, would stand for the right to possess violent erotica? Labour support the provision uncritically, denying it appropriate scrutiny.

Such a serious proscription, which might endanger harmless women and men, merits its own public debate, not back-door legislation. Solicitor Myles ‘ObscenityLawyer’ Jackman, who represented Walsh, highlights the dangerous subjectivity of judging pornography “realistic”, plus the “absence of any evidence proving…a causal link” between such material and Cameron’s “normalise(d) sexual violence against women”. A representative survey of 19,000 UK adults cited by three academics shows 1/3 of adult fantasies include domination or submission, and about 5% of Britons fantasise about delivering/experiencing violence. These academics’ parliamentary evidence repeated Jackman’s scepticism of the link between pornography and real-world crime. Groups like Rape Crisis South London and the End Violence Against Women Coalition assert such pornography does promote dangerous beliefs. The government itself “believes such images are unacceptable and most people would regard them as disgusting and deeply disturbing,” implying the majority’s moral distaste is grounds for legislation.

Groups like Sex & Censorship and Backlash protest the bill’s wording and justification, arguing millions of law-abiding kink practitioners might be criminalised for depicting safe, consensual, private acts. Sexual minorities including the LGBT community, bondage enthusiasts, horror-movie recreators and “vampire and goth enthusiasts who use fake blood in roleplay” could be covered, Backlash told me. Even Rackley and McGlynn, the Durham University academics who championed this law for years, criticise the bill’s wording, demanding clarification specifically banning “realistic images”, protection for “private depictions of consensual BDSM activity” and consideration of context.

Sex-positive feminism raises questions over what the bill would achieve. Arguments that violent pornography (and general sexual imagery) warps childhood development, perpetuates objectification and enables rape culture are valid, but attacking one subsection of pornography won’t stop children seeing questionable images. They fill celebrity magazines, tabloids, advertising and primetime TV.

In terms of child protection, then, this may be window-dressing. It’s far more important for schools to promote effective sex education covering consent, gender, identity and relationships, rather than a “see no evil” approach. Such education is woefully lacking and outdated. Meanwhile the government has cut funding for sexual health services for vulnerable teens and youth services, and is attacking endangered women’s panic rooms via the “bedroom tax”.

The government may be simultaneously attacking the harmless, and harming those who are helpless. The extension of extreme pornography censorship is dangerous because it’s had minimal public discussion, the wording is poorly considered, and it’s unlikely to address the problem used to promote it.

This article was published on April 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for