13 Mar 2014 | India, News and features, Pakistan

Improbable as it may seem, but 67 Kashmiri university students were briefly charged with sedition for cheering for Pakistan, and celebrating its win over India, during an Asia Cup cricket match in early March.

Sections of the Indian Penal Code that they were charged under were the following:

Section 124a – “Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law..”

Section 153 – “Whoever malignantly, or wantonly by doing anything which is illegal, gives provocation to any person intending or knowing it to be likely that such provocation will cause the offence of rioting to be committed shall..”

Section 427 – “Whoever commits mischief and thereby causes loss or damage to the amount of fifty rupees or upwards..”

The students were watching the match in Meerut, at the Swami Vivekanand Subharti University when the ruckus started. According to conflicting reports, the hooting of the Kashmiri students at Pakistan’s win caused those supporting India to chase them and throw stones at their rooms. The Kashmiri students protested the next day, but the university officials suspended them for three days as “resentment was growing in other hostels because of their behavior.” The police charged them under the Indian Penal Code. After a public outcry, the Uttar Pradesh police dropped the charges, however, there is a battle of words between the police and university officials as to who initiated the charges against the students.

The incident, once again, has exposed the fragile faultlines between Kashmir and India – and the perceived disloyalty of the Kashmiri Muslims to India. The controversy has brought about some harsh reactions, including a tweet by famous lyricist Javed Akhtar that said – “Why the suspension of those 67 Kashmiri students who cheered Pakistan is revoked. They should be rusticated and sent back to Kashmir.” Others, like Shivam Vij, took a more nuanced position, stating that, “not taking action against them would have escalated the violence at the university and in the city. The Indian students at the university were responding with the same sentiment that makes Kashmiri Muslims suspect their Hindu minority: the sentiment of nationalism. How acceptable would it be to a Pakistani if some in Pakistan openly and publicly cheered for the Indian cricket team in a match against Pakistan?”

Tidbits from Kashmir also help cement this view of the Muslims from the Kashmir Valley to the rest of India. Reports that firecrackers celebrated Pakistan’s win all night, and that a skirmish between Indian army personnel and local Kashmir youth celebrating the results of the match ended in a stabbing. There have also been defiant editorials from Pakistan countering the action against the students, declaring that, “it is not the win of Pakistan but the loss of India against any cricket playing nation that revives interest for cricket in Kashmir. India’s loss is a temporary relief from all the melancholy and grief that the people of Kashmir go through on a daily basis, inflicted by the Indian state and its military architecture.”

While this incident in question might have, on the surface, been about cricket and extremely ungentlemanly behavior, very quickly it seemed to have translated into politics as usual. A outcry about serious charges against university students – Kashmiris who had travelled far from home to obtain an Indian degree – was raised by many Indians in the media, by the Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, and international groups. Many of these students were in Meerut given under the PMSSS, or the Prime Minister’s Special Scholarship Scheme, meant to enhance job opportunities for Kashmiri youth, meant mainly for low-income families. This is part of a larger drive to assimilate Kashmiri youth into the mainstream economic and educational life of India.

Indian Express’s Shekhar Gupta lamented the controversy given cricket’s globalized nature where it is increasingly normal to cheer for favourite player from another country. Instead he feels that “India’s majority has a minority complex” and this is coming to the fore “when the BJP is surging ahead, and not because of any mandir, tension with Pakistan, or rash of terror attacks. And when, in fairness, you have to acknowledge that there isn’t even a vaguely communal appeal in its leader Narendra Modi’s campaign message. India has had a 13-year period of total peace, unprecedented in its independent history. There has been a steep decline in terror incidents. Even the Maoists seem to be shrinking slowly. And yet, our level of jingoism is as if we were approaching an imminent war, as if India were under siege, its borders getting violated with impunity, the enemy at the gates.” Many echo Gupta’s view, fearing that those who believe the BJP under Narendra Modi will form government after the elections in April 2014, might be quick to adopt the jingoistic Hindu nationalism the party was based on.

Adding a layer to this incident is an interesting point of view offered by journalist Prayaag Akbar who writes about India’s many Muslims who feel affinity towards Pakistani cricket team, but are rarely called out for it, unlike the Kashmiri Muslims. He writes – “that some Indian Muslims, not just Kashmiris, support Pakistan during cricket matches must be acknowledged. But categorisation is self-fulfilling, some will say, and sport excites tribalism. It does not immediately follow—and this seems to be the consideration at the crux of the issue—that they will support Pakistan in a war against India. Yet it does not immediately follow that they will not, either. No one on either side of the debate can assert their position with complete confidence. What we can say with certainty is there has been a failure of assimilation, that has in part been caused by a rarely acknowledged, yet generally accepted, narrowed definition of what it means to be Indian.”

Cricket, criticisms and cartoons cannot be simply deemed seditious by the Uttar Pradesh police because they are problematic. And, ironically, this is in the shadow of the largest democratic exercise in the world, the Indian elections, a month away.

This article was published on March 13, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Mar 2014 | News and features, Uncategorized

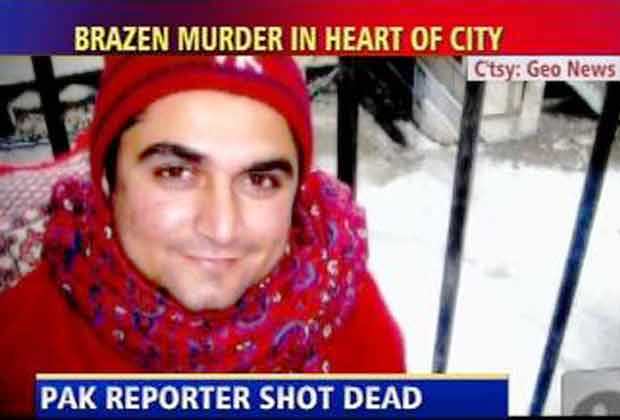

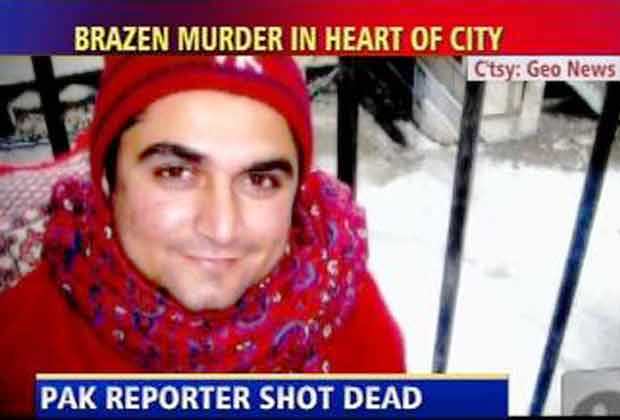

(Image: GEO TV)

On 1 March an anti-terrorism court in Pakistan, found six men guilty of the murder of 28-year old journalist Wali Khan Babar. Four have been sentenced to life imprisonment, and two, in absentia, were sentenced to death.

The young reporter was shot dead on January 1, 2011, while working for GEO TV in the Liaquatabad area of Karachi. According to Committee to Protect Journalists, his was a work-related murder.

Convictions for attacks on journalists can be complicatd in Pakistan. Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who was convicted for the murder of US reporter, Daniel Pearl is the only previous journalist killer to have been sentenced to death. However, Pearl’s case remains in dispute and Sheikh has been incarcerated at the Hyderabad Central Jail for the last 12 years. His lawyers are appealing the conviction, saying he was framed. The confusion arose after Khalid Sheikh Mohmmad (currently being held in Guantanamo) confessed to the murder.

Therefore, Mazhar Abbas, former secretary general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) while terming this month’s conviction as an “important decision” remains sceptical that Babar’s family will get justice given the abysmally low conviction rate once the case goes to higher courts. “It may take years to get a decision if the case goes to the Sindh High Court for appeal,” he said pointing to deep-rooted “corruption” that prevailes in the judicial system.

But that is not the only reason for the delay in justice. Despite setting up anti-terrorist courts (ATCs) for speedy disposal of cases, the conviction rate has not made an appreciable difference. People like former prosecutor general of Sindh province, Shahadat Awan, links the high rate of acquittal (almost 73 percent), to weak investigation and witnesses retreating.

Since Babar’s trial began, six witnesses, a lawyer and two policemen linked to the investigation have been assassinated.

After these murders, and amid threats to the prosecutors and lawyers, the trial was shifted from Karachi to another city in Sindh, Shikarpur. “The case has been tried under extremely difficult circumstances and to that extent I am satisfied,” acknowledged Abbas.

However, not everyone is wholly satisfied.

According to Zohra Yusuf, chairperson of the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) “justice has not been fully served as two culprits are absconding and six witnesses and a prosecution lawyer were killed while the case was being heard.”

For Ambreen Agha, research assistant with New Delhi’s Institute for Conflict Management, the conviction was a welcome step but ensuring justice was equally important.

“It is a significant step in a place where a culture of impunity dominates” she said, citing the example of Malik Ishaq, a militant leader, who, despite his involvement in the massacre of minority Shias and his association with the defunct terrorist outfit, Lashkar e Jhangvi, “goes scot free”.

At the same time, a recent attack on the Islamabad courthouse showed how vulnerable those delivering justice were.

“Despite the threat that looms large on any functioning institution of Pakistan, the judiciary will have to stand strong and determined in bringing justice in this case. The onus lies on the judiciary despite the precarious times in Pakistan,” Agha emphasized.

Nevertheless, for the media community, the conviction of Babar’s killers is historic.

Media analyst, Adnan Rehmat, said the verdict was a “turning point in the battle for defence of beleaguered media practitioners” and Abbas termed it a “ray of hope” showing that Pakistan can improve its record on protecting journalists and pursuing their killers.

But Ambreen Agha warned that a sustained policy was required to “protect the media from the extreme intolerance of the militants and the political class”.

Further, she added: “The political lobby and its attempts to shrink spaces for freedom of expression by shutting down private TV channels, intimidating and blocking certain media outlets, has, in the past, emboldened the terrorists and opened the spaces for the perpetrators of violence.”

This article was posted on March 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

8 Mar 2014 | Azerbaijan News, News and features

International Women’s Day is a day to remember violence against women, the education gap, the wage gap, online harassment, everyday sexism, the intersection between sexism and other -isms, and a whole host of other issues to make us realise we’ve still got a long way to go. A day to demand continued progress, and a day to pledge to work to achieve it.

But it is also a day to celebrate. To appreciate the fantastic achievements that are made every day, everywhere, by women from all walks of life. It’s a day to be grateful to the women who dedicate their lives to fighting on the front lines to protect rights vital to us all. We want to shine the spotlight on women who have stood up for freedom of expression when it’s not the easy or popular thing to do, against fierce opposition and often at great personal risk. The following eight women have done just that. We know there are many, many more. Tell us about your female free speech hero in the comments or tweet us @IndexCensorship.

Meltem Arikan — Turkey

Meltem Arikan

Arikan is a writer who has long used her work to challenge patriarchal structures in society. He latest play “Mi Minor” was staged in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013, and told the story of a pianist who used social media to challenge the regime. Only a few months after, the Gezi Park protests broke out in Turkey. What started as an environmental demonstration quickly turned into a platform for the public to express their general dissatisfaction with the authorities — and social media played a huge role. Arikan was one of many to join in the Gezi Park movement, and has written a powerful personal account of her experiences. But a prominent name in Turkey, she was accused of being an organiser behind the protests, and faced a torrent of online abuse from government supporters. She was forced to flee, now living in exile in the UK.

I realised that we were surrounded, imprisoned in our own home and prevented from expressing ourselves freely.

Anabel Hernández — Mexico

Anabel Hernández (Image: YouTube)

Hernández is a Mexican journalist known for her investigative reporting on the links between the country’s notorious drug cartels, government officials and the police. Following the publication of her book Los Señores del Narco (Narcoland), she received so many death threats that she was assigned round-the-clock protection. She can tell of opening the door to her home only to find a decapitated animal in front of her. Before Christmas, armed men arrived in her neighbourhood, disabled the security cameras and went to several houses looking for her. She was not at home, but one of her bodyguards was attacked and it was made clear that the visit — from people first identifying themselves as members of the police, then as Zetas — was because of her writing.

Many of these murders of my colleagues have been hidden away, surrounded by silence – they received a threat, and told no one; no one knew what was happening…We have to make these threats public. We have to challenge the authorities to protect our press by making every threat public – so they have no excuse.

Amira Osman — Sudan

Amira Osman (Image: YouTube)

Amira Osman, a Sudanese engineer and women’s rights activist was last year arrested under the country’s draconian public order act, for refusing to pull up her headscarf. She was tried for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, an offence potentially punishable by flogging. Osman used her case raise awareness around the problems of the public order law. She recorded a powerful video, calling on people to join her at the courthouse, and “put the Public Order Law on trial”. Her legal team has challenged the constitutionality of the law, and the trial as been postponed for the time being.

This case is not my own, it is a cause of all the Sudanese people who are being humiliated in their country, and their sisters, mothers, daughters, and colleagues are being flogged.

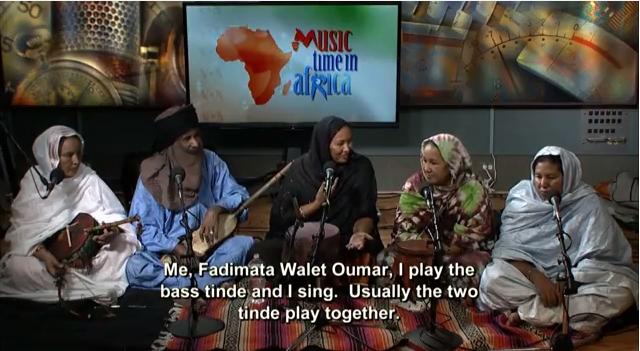

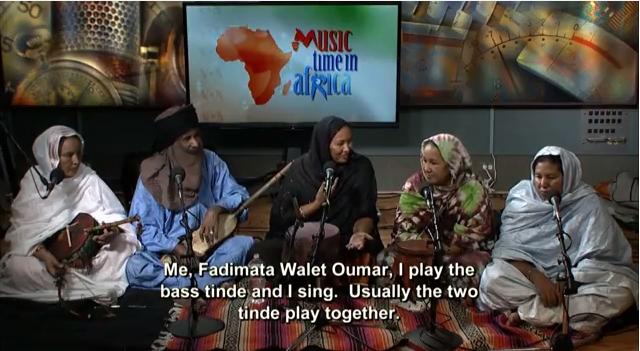

Fadiamata Walet Oumar — Mali

Fadiamata Walet Oumar with her band Tartit (Image: YouTube)

Fadiamata Walet Oumar is a Tuareg musician from Mali. She is the lead singer and founder of Tartit, the most famous band in the world performing traditional Tuareg music. The group work to preserve a culture threatened by the conflict and instability in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, an islamists rebel group, has imposed one of the most extreme interpretations of sharia law in the areas they control, including a music ban. Oumar believes this is because news and information is being disseminated through music. She fled to a refugee camp in Burkina Faso, where she has continued performing — taking care to hide her identity, so family in Mali would not be targeted over it. She also works with an organisation promoting women’s rights.

Music plays an important role in the life of Tuareg women. Our music gives women liberty…Freedom of expression is the most important thing in the world, and music is a part of freedom. If we don’t have freedom of expression, how can you genuinely have music?

Khadija Ismayilova — Azerbaijan

Khadija Ismayilova

Ismayilova is an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist, working with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is know for her investigative reporting on corruption connected to the country’s president Ilham Aliyev. Azerbaijan has a notoriously poor record on human rights, including press freedom, and Ismayilova has been repeatedly targeted over her work. She was blackmailed with images of an intimate nature of her and her boyfriend, with the message to stop “behaving improperly”. This February, she was taken in for questioning by the general prosecutor several times, accused of handing over state secrets because she had met with visitors from the US Senate. In light of this, she posted a powerful message on her Facebook profile, pleading for international support in the event of he arrest.

WHEN MY CASE IS CONCERNED, if you can, please support by standing for freedom of speech and freedom of privacy in this country as loudly as possible. Otherwise, I rather prefer you not to act at all.

Jillian York — US

Jillian York (Image: Jillian C. York/Twitter)

Jillian York is a writer and activist, and Director of Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). She is a passionate advocate of freedom of expression in the digital age, and has spoken and written extensively on the topic. She is also a fierce critic of the mass surveillance undertaken by the NSA and other governments and government agencies. The EFF was one of the early organisers of The Day We Fight Back, a recent world-wide online campaign calling for new laws to curtail mass surveillance.

Dissent is an essential element to a free society and mass surveillance without due process — whether undertaken by the government of Bahrain, Russia, the US, or anywhere in between — threatens to stifle and smother that dissent, leaving in its wake a populace cowed by fear.

Cao Shunli — China

Cao Shunli (Image: Pablo M. Díez/Twitter)

Shunli is an human rights activist who has long campaigned for the right to increased citizens input into China’s Universal Periodic Review — the UN review of a country’s human rights record — and other human rights reports. Among other things, she took part in a two-month sit-in outside the Foreign Ministry. She has been targeted by authorities on a number of occasions over her activism, including being sent to a labour camp on at least two occasions. In September, she went missing after authorities stopped her from attending a human rights conference in Geneva. Only in October was she formally arrested, and charged for “picking quarrels and promoting troubles”. She has been detained ever since. The latest news is that she is seriously ill, and being denied medical treatment.

The SHRAP [State Human Rights Action Plan, released in 2012] hasn’t reached the UN standard to include vulnerable groups. The SHRAP also has avoided sensitive issue of human rights in China. It is actually to support the suppression of petitions, and to encourage corruption.

Zainab Al Khawaja — Bahrain

Zainab Al Khawaja

Al Khawaja is a Bahraini human rights activist, who is one of the leading figures in the Gulf kingdom’s ongoing pro-democracy movement. She has brought international attention to human rights abuses and repression by the ruling royal family, among other things, through her Twitter account. She has also taken part in a number of protests, once being shot at close range with tear gas. Al Khawaja has been detained several times over the last few years, over “crimes” like allegedly tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. She had been in jail for nearly a year when she was released in February, but she still faces trials over charges like “insulting a police officer”. She is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence.

Being a political prisoner in Bahrain, I try to find a way to fight from within the fortress of the enemy, as Mandela describes it. Not long after I was placed in a cell with fourteen people—two of whom are convicted murderers—I was handed the orange prison uniform. I knew I could not wear the uniform without having to swallow a little of my dignity. Refusing to wear the convicts’ clothes because I have not committed a crime, that was my small version of civil disobedience.

This article was posted on March 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Mar 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

(Image: LEGOLAND Windsor Resort)

A day out for Muslim families at the childrens’ theme park Legoland in Windsor was cancelled last week after multiple threats were received from far-right groups. The Daily Mail was labelled “hateful” by Muslim organisations for its coverage of the episode.

According to press reports members from the English Defence League and a splinter group known as Casuals United had both threatened to protest at the day-out, which was organised by the Muslim Research and Development Foundation (MRDF), and had sent threatening letters to MRDF offices as well as staff at Legoland.

A spokesperson for MRDF told Index: “They terrorised staff at Legoland, staff at MRDF and aimed to terrorise children and families on the day of the event.” He added: “Several articles in the national press helped fuel further hatred and resentment.”

The event, which was due to go ahead on 9 March, was cancelled after Legoland and MRDF consulted with the local police. “The owners of Legoland made the decision to cancel the event in consultation with the MRDF”, a police spokesperson told Index

The police are known to be investigating several malicious messages sent by members of the EDL and Casuals United in the run-up to the cancellation. “Thames Valley Police can confirm it is investigating reports of offences committed under the Malicious Communications Act (1988),” said the spokesperson. They confirmed that the investigation related to several social media messages sent in the days leading up to the cancellation.

It is understood from sources at Legoland that the Anti-Fascist League, who had planned a counter-demonstration against the EDL and Casuals United, was also considered a threat to the peaceful day out.

Fierce criticism has been levelled at trustee and chairman of the MRDF, Haitham al-Haddad, an Islamist preacher, over allegations of being anti-Semitic, homophobic and in favour of female genital mutilation. Al-Haddad describes himself as a Muslim community leader and television presenter, of Palestinian origin. He sits on the boards of advisors for several Islamic organisations in the United Kingdom, including the Islamic Sharia Council. He is the chair and operations advisor, and a trustee, for the Muslim Research and Development Foundation. Al-Haddad, who is outspoken in his criticism of British foreign policy, has been banned from speaking at a number of British universities because of his alleged views.

The MRDF, based in East London, undertakes research and publishing programmes, corporate retreats and development programmes, organises conferences, seminars and lecture tours and analysis of news, information and media material.

Grassroots far-right group the English Defence League had planned to hold protests outside the theme park if the day went ahead. In a press release on their website, they described al-Hatham as a “known hate preacher,” who “thinks Jews and gays should be killed, Israel destroyed, unbelievers converted or killed, women beaten into house slaves…and Osama Bin Laden should be held in high esteem.”

A spokesperson from Legoland told Index: “This was about lots of families having a day out. The park is closed from November to March and we open for private events. This one had no alcohol and halal food available, alongside non-halal. Other than that it was a normal event.” The spokesperson also added: “Anyone was able to buy these tickets – it was not a Muslim-only day.”

Legoland said 9000 tickets were available but it was unclear how many had been sold at the time the event was cancelled. Their spokesperson also confirmed that MRDF had paid a fee to hire the park exclusively. MRDF was responsible for selling tickets to their own members.

In a separate statement released on their website, Legoland made clear that they believed the far-right groups should be blamed for the event cancellation: “Sadly it is our belief that deliberate misinformation fuelled by a small group with a clear agenda was designed expressly to achieve this outcome.” The statement added: “We are appalled at what has occurred, and at the fact that the real losers in this are the many families and children who were looking forward to an enjoyable day out at LEGOLAND.”

The Daily Mail has also been slammed in an open letter to their editor, Paul Dacre, over “hateful” coverage of the events leading up to the cancellation.

In a piece written by columnist Richard Littlejohn on Tuesday 18 February, titled “Jolly jihadi boys’ outing to Legoland”, Muslim groups say the paper “deployed hateful Muslim stereotypes” and “used slurs commonly found in racist and far-right websites.”

The article referenced a coach that would be “packed with explosives” and that might “blow up” after stopping in Parliament Square. At Legoland, guests would be “reminded that music and dancing are punishable by death”. Later, girls would be expected “to report to the Kingdom of the Pharaohs for full FGM inspection” while boys would “report to the Al-Aqsa recruiting tent outside the Land of the Vikings for onward transportation to Syria.”

The letter of complaint was published by the Muslim Council of Britain, and co-signed by more than twenty five other Muslim organisations.

This article was posted on March 5, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org