14 Feb 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1487082444020{padding-top: 250px !important;padding-bottom: 200px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Bahrain_2011.jpg?id=85632) !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Bahrain’s Day of Rage on 14 February 2011 kickstarted one of the largest popular uprisings in the country’s history. Bahraini youth took to social media and called on people “to take to the streets” in protest of the endemic corruption, discrimination and injustice.

Many of the 55 peaceful demonstrations on the day were met with violence from police and soldiers, leaving more than 30 protesters injured and one dead.

Six years on, the Bahraini government has fostered an atmosphere of fear and repression, through the detention and torture of opposition leaders and supporters, designed to stifle all dissent.

Here are 10 articles and reports explaining where Bahrain is today and how it got here.

“Two Bahrainis appear to be at imminent risk of execution despite the authorities’ failure to properly investigate their allegations of torture, Human Rights Watch said today. Both Mohamed Ramadan and Husain Ali Moosa have disavowed confessions that they allege were the result of torture and that were used as evidence in a trial that violated international due process standards.”

– Human Rights Watch, 23 January 2017

“Bahrain continuously stifles free speech and silences critics. It also has the highest prison population per capita in the Middle East, including 3,500 prisoners of conscience.”

– Index on Censorship, 23 January 2017

The IP Spy Files explore how Bahrain’s government silences anonymous online dissent by targeting activists with ispy links on social media networks and subsequently arresting them.

“On 15 March 2011 Bahrain’s king brought in a three-month state of emergency, which included the through establishing of military courts known as National Safety Courts. The aim of the decree was to quell a series of demonstrations that began following a deadly night raid on 17 February 2011 against protesters at the Pearl Roundabout in Manama, when four people were killed and around 300 injured.”

– Index on Censorship, 17 August 2016

“2015 saw a year-on-year increase of the systemic use of arbitrary detention of those who speak out against the Bahraini regime. Index calls on the Bahraini authorities to end arbitrary arrests and immediately release all prisoners of conscience.”

– Index on Censorship, 2 June 2016

“Bahrain, in particular, has intensified the use of stripping citizenship from those who dissent or speak out in protest as a form of punishment. Since 2012 – when the country’s minister of the interior made 31 political activists stateless, many of whom were living in exile – 260 citizens have fallen victim, 208 in 2015 alone. Eleven juveniles, at least two of which have received life sentences, and 30 students are known to be among them.”

– Index on Censorship, 28 April 2016

“Contrary to the popular narrative on Bahrain, sectarianism was not the dominant motivating factor behind the 2011 uprising or the protest movements which preceded it.”

– Middle East Institute, 19 January 2016

“As a family, we’ve decided that it would be important for us to write about the hardships we have personally endured on an individual and family level as a direct consequence of the punishment handed down by the government, which fears the pure and peaceful expression of speech.”

– Index on Censorship, 25 October 2015.

“Bahrain’s prison authorities continue to humiliate, torture and mistreat inmates at Jau Prison […] [P]sychological and physical torture, prevention of medical care, and massive overcrowding remain a systemic failure of Bahrain’s prison system.”

– BIRD, 26 June 2015

“Following the fall of authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt, hundreds of thousands of Bahraini protesters took to the streets of Manama, the capital city, on 14 February, 2011, to peacefully call for democratic reform. Officials were quick to crack down on protests, and the access of the international media was limited almost immediately after the start of the protests. Unlike other citizens demonstrating across the Arab World in 2011, the protests in Bahrain have received very little coverage, particularly considering the disproportionate number of people jailed and killed in the tiny country of 1.2 million people. ”

– Index on Censorship, 15 January 2012

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Image credit: Al Jazeera English. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1487179952538-7949f96c-116b-3″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Oct 2016 | Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This article is from the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which focuses on anonymity.

I have a name. I am not anonymous. But what if I didn’t have a name? What if I could enjoy the luxury of being safe at home in Bangladesh, and not far away in Germany?

I could have distanced myself from my identity, adopted a pseudonym and continued to write in Bangladesh. Had I done so, my family wouldn’t have to spend each moment in fear and anxiety. My sister wouldn’t have to wake up from nightmares about rape threats. But I am not anonymous. I carry my name and history with me. And so the possibility of an unnatural death haunts me.

Since 2013, my name has surfaced on multiple “hit lists” targeting Bangladeshi bloggers and other activists. I still regularly receive death threats from religious extremists on Facebook and other social media. One simply told me, “It’s your turn now.”

My words often create problems for others. I see myself as writing for the freedom of various groups, for the rights of oppressed communities, for women, for the sexually marginalised. In my debut book Chastity Versus Polygamy, I addressed the patriarchal notion of purity that is assigned to women’s sexuality; this was considered controversial and it enraged many.

I strongly believe that all human beings possess an equal right to express themselves, to assert their ideas and to be recognised for who they are and what they want to be. When the identity of the writer is out in the open, along with a certain level of insecurity comes a burden of responsibility that commits the writer to his or her words. This is why anonymity never appealed to me. I had faith in the democratic setup of my country, Bangladesh. But the state failed to uphold our freedom by suggesting we should stop writing, rather than that terrorism should stop. So I left.

Anonymous bloggers and activists in Bangladesh come from all parts of the ideological spectrum. They include religious radicals, communists, liberals. Unfortunately, certain sections of this anonymous community aim to create chaos, rather than a constructive democratic debate. A number of them publish hate speech, or post videos which are meant to incite violence.

Generally, however, the bloggers are on the receiving end of aggression. Sometimes, even anonymity is no protection. Those who would silence them are often incredibly adept at technological espionage, and can all too easily crack their identities. In March 2015, anonymous atheist blogger Washiqur Rahman Babu was traced and killed in broad daylight outside his residence. Even I didn’t know his identity at the time.

In the face of threats, therefore, going anonymous is hardly a foolproof solution. However, it may not always be feasible to declare one’s identity under dire circumstances, which is the case in many places across the world right now. Anonymity might turn to be one of the necessary shields in the larger, longer battle for free speech.

This article is from the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Ananya Azad, a Bangladeshi writer and blogger, is currently in exile in Germany. His father, author Humayun Azad, was the victim of assassination attempts, and later died in mysterious circumstances.

You can order your copy of the latest issue here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91922″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/030642208701600613″][vc_custom_heading text=”Testimony of an ex-censor” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F030642208701600613|||”][vc_column_text]June 1987

Once a censor in the Syrian Ministry of Information, the anonymous source details the invasion of privacy and censorship the government employs.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80637″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422015591456″][vc_custom_heading text=”Blogging in Bangladesh” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422015591456|||”][vc_column_text]June 2015

A series of murders of secular bloggers by religious fundamentalists in has presented clear warnings for bloggers to watch what they say.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422010362466″][vc_custom_heading text=”Egyptian gate to freedom” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422010362466|||”][vc_column_text]March 2010

Mohamed Khaled reports that the Egyptian government continues to harass bloggers, but they’ve become a vital source of information even for the state media. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2016 Index on Censorship magazine explores topics on anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world.

With: Valerie Plame Wilson, Ananya Azad, Hilary Mantel[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80570″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/the-unnamed/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Sep 2016 | Magazine, mobile, News and features, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras, Youth Board

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, The Unnamed: Does anonymity need to be defended?, Index’s contributing editor for Turkey, Kaya Genç, explores anonymous artists in Turkey. In the piece the artists discuss how vital anonymity is in allowing them to complete their more controversial work. The Index on Censorship youth advisory board have taken inspiration from this piece for their latest task, in which they investigate anonymous art around the world.

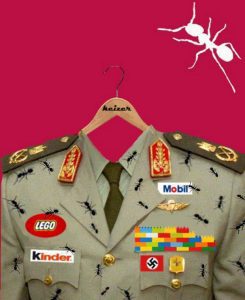

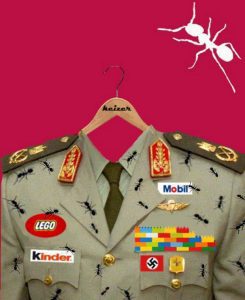

Keizer by Constantin Eckner

Ants feature in Keizer’s work to sybolise “the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism”. Image: Keizer

Prior to the January 25 Revolution political street art was anything but common in Egypt, yet it has proliferated in public spaces in the aftermath of the revolution. One of the most productive street artists in Cairo is Keizer, who has gained popularity and notoriety in recent years. Like Banksy and other street artists, he uses the well-known stencil technique to empower his fellow countrymen, and people in general, with his thought-provoking work. He likens people to ants, which are featured in most of his graffiti. Keizer explains on his Facebook account that the ant “symbolises the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism. They are the working class, the common people, the colony that struggles and sacrifices blindly for the queen ant and her monarchy.”

Asked about the reason for protecting his identity, Keizer said: “I am very concerned over my safety and the repercussions of street art which I’ve already had a taste of, especially with this current regime. Including death threats,

Egyptian street artist Keizer has gained popularity in recent years. Image: Keizer

my twitter account was hacked twice. In the past five years of working on the street I’ve been caught once. I came out of it with a few bumps and bruises, nothing major. I consider myself lucky that I came out one day later.

“You can imagine that being caught here is very different than being caught in Europe. There is no proper procedure and that makes you a victim of the person handling you, and the uncertainty of what comes next. Graffiti is a grey area here, they don’t have any definition or classification for it in the books, so they make it up as they go along, taking you for the fear ride. It’s all under vandalism, so they can make it look small or escalate it to exaggerated levels. For instance, you can be dubbed as a political traitor; it can be considered racketeering; they can glue your name to any political movement unpopular with the people…etc.”

Tall walls, low profiles: Icy and Sot by Layli Foroudi

Icy and Sot describe themselves as stencil artists from Tabriz, Iran. As for their identities, they reveal only that they are brothers, born in 1985 and 1991. Their work is created under pseudonyms in countries around the world, including Iran, USA, Germany, Norway, and China, on legal and illegal walls as well as in galleries.

The anonymous duo, who paint on themes like human rights, censorship, and justice, say that charges against artists in Iran make going public risky.

“Pseudonyms help us to keep a low profile,” the brothers explained in an interview with ArtInfo, “Being arrested in Iran is completely different, because they charge you with crimes that you have not even committed, like Satanism or political crimes.”

Their work often uses striking human faces in black and white to make statements about politics and the environment, to call for peace, and to direct messages at the government of Iran. In 2015, Icy and Sot used their art to protest for freedom of expression in Iran, prompted by the arrest and 18-month imprisonment of Atena Farghadani, an Iranian artist who was detained for publishing a cartoon that satirised the Iranian government as animals. In solidarity, they stenciled a tribute piece depicting Farghadani with a backdrop of protesters on a wall in Brooklyn.

Maeztro Urbano’s fight to change a criminal image by Ian Morse.

In the most recent data, Honduras has the highest homicide rate in the world, with 84 intentional homicides per 100,000 people in 2013. The prominence of drug trafficking and ubiquity of poverty does not improve its reputation.

To some Hondurans, their country’s international image has done nothing but hurt citizen’s attempts to improve daily life in the country’s bustling cities and lively cultural centers. Maeztro Urbano and his friends became the face of an urban street art project to disrupt the atmosphere of crime and reveal another side of the country outside of the headlines.

His projects range from adjusting street signs promoting gender equality to vandalising billboards with corrupt politicians, to wall graffiti showing the effect of violence on children. Working his day shifts in the advertising industry, Maeztro Urbano said he wants to contribute more to his country than proliferating consumerism.

“Change should start within society. With each individual,” El Maestro – as he is also called – told The Creators Project. “To have respect for the lives of others, to respect the right to sexual diversity, to a better education.”

“If we don’t change that as a society and as individuals, we will never be able to change as a country.”

Assailants in Honduras have not been very hospitable to those reporting on crime or those wishing to express their identity. Faced with police harassment and shootings from unknown attackers, Maeztro Urbano chooses to wear a mask while he works to spread messages of hope around the country.

Bleeps.gr: Over a decade of political artivism in Athens by Anna Gumbau.

Bleeps.gr is one of Greece’s most prominent street artists, having painted murals on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. Image: Bleeps.gr

“I have been radically oriented to the political discourse, utilising the public sphere, and I am not afraid or discouraged”, Bleeps.gr, one of the most prominent Greek street artists, told Index.

Bleep.gr has been designing murals, that are mostly critical of the austerity policies imposed to Greece, on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. The Greek social turmoil has had a strong influence on his artwork, not only in his scenes, but even in his methods. “I buy very cheap materials and can’t afford those impressive equipment to create a mural”, he said in an interview with Street Art Europe.

Bleeps.gr chooses to use a pseudonym as an attempt to challenge “the institutionalised perception of the identity”, he told Index. While he is not afraid of the state authorities, he points at art institutions, such as galleries, exhibitions and festivals, who reject and exclude his art. “Most of the censorship I have received has come from other artists, especially the ones related to systemic initiatives, who in the past years have removed all of my works from the city center” he said. Greek political street artists often suffer from the exclusion of art galleries and exhibitors; in the summer of 2013, the CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS? street art festival in Athens, which celebrates the value of street art in the current political happenings, invited 20 artists from different European countries but failed to invite any Greek artists.

Nevertheless, Bleeps.gr stresses the fact that the internet “has provided a virtual field of allocation”, and most of the political street art discourse happens there.

Bleeps.gr highlights the mechanisms of such institutions to “absorb street artists” and make them become part of the art “business”, adding: “the majority of them nowadays serve gentrification policies and turn policies and turn political art into a spectacle for tourist pleasure”.

King of Spades by Sophia Smith-Galer.

When it comes to anonymous artists, the art tends to speak far louder than any speculation into the artist themselves. This anonymous artist in Lebanon is no Arab Banksy that lurks tantalisingly close to the limelight; this artist could quite literally be anyone, and the lack of anybody claiming the piece as their own is revelatory of the grave reality of artists in developing countries that test the patience of despots and tyrants.

Despite its tired and no longer relevant label “Paris of the Middle East”, even the dazzlingly artistic city of Beirut, Lebanon, can’t quite get away with hanging something like this banner, depicting the late Saudi Arabian monarch King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz as a brutal King of Spades. Shortly after its creation in 2013, the Lebanese state prosecutor ordered an investigation to reveal the source of these posters after complaints from Saudi Ambassador Ali Awad Asiri.

It seems that nobody got caught, and nor do I particularly want to dwell on what would have happened to the artist if they had. But in the Middle East, such a daring artistic expression must be forbidden fruit in a region of gagged political artistry; demonstrated no better than in this mysterious artist who gambled with the assumed impunity of that gentleman with the bloodied scimitar.

Dede Bandaid by Shruti Venkatraman.

One of Dede Bandaid’s most well known works, a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014. Image: Dede Bandaid / Wikicommons

Dede Bandaid is an anonymous Israeli artist who has added colour to Tel Aviv’s streets with thought provoking and politically relevant street art. His artistic career began in 2000 during his compulsory military service, and most of his earlier pieces demonstrated a clear anti-establishment sentiment. His more recent works, following the end of his stint in the military, aim to communicate social and political messages. One of his most well known works is a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014.

Dede enjoys using public spaces as a canvas as this approach allows freer and more controversial expression, while also being accessible to and viewable by a larger audience especially when the street art is photographed and its images are circulated online. He also makes use of traditional symbols of peace, like the white dove, and frequently incorporates Band-Aids that represent healing and remedy in his artwork, with “Bandaid” being the pseudonym he signs on all his pieces. Over time, Dede’s style has evolved from stencilling to free-hand painting and collage and he interestingly also exhibits certain pieces in galleries across the world.

Cabbage Walker in Kashmir by Niharika Pandit.

A pheran-clad man walks around with a cabbage on a leash in the neighbourhoods of Srinagar, Kashmir. This performance act that he presents is inspired by Chinese artist Han Bing’s “Walking the Cabbage” social intervention work. While Bing chose to walk the cabbage to reflect on the changing values in the Chinese society, where once cabbage was a subsistence food product but is now only embraced by the poor, in Kashmir, this anonymous artist aims to normalise the cabbage walking to show the absurdity of militarisation in the region. Both the performances employ cabbage as an element of satire to expose the irony inherent in what how elitism and militarisation come to be normalised in societies across the world.

The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker writes on his blog, “I as a Kashmiri am willing to recognise walking the cabbage as part of the Kashmiri landscape but I will never accept the check posts, the bunkers, the army camps, the torture centers, the barbed wire, the curfews, the arrests, the toxic environment of conflict and war, as part of the same.”

This performance artist chooses to remain anonymous as it helps in focusing on the message and not the messenger. The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker says that he represents all Kashmiri lives under militarisation thereby revealing the artist’s identity becomes unimportant here.

Cracked pavements in Budapest by Fruzsina Katona.

Anonymous volunteers have joined the satirial political party the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) to paint cracked pavement on the streets of Budapest. Image: Fruzsina Katona

Anonymity does not necessarily mean that one is trying to hide his or her identity. Sometimes the identity of the person is utterly irrelevant. In Budapest, several anonymous volunteers are painting the streets of the city.

The pavement on the streets of the Hungarian capital are falling apart, ruining the image of the city and endangering those who walk on it. Authorities are known to do very little to fix the problem, but something had to be done. Hungary’s satiric political party, the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) called for action and its artsy, anonymous volunteers started colouring the cracked pavement pieces resulting in dozens of cheerful spots across the city.

Unfortunately, there are some who find quarrels in a straw, and the police were called on the ad-hoc artists while they were peacefully decorating the pavement in a touristic neighbourhood. Now the volunteers are being prosecuted with vandalism.

But we still do not know their identity or how many of them are out decorating. All we know is that now we look at colourful patches of pavements while running our errands, instead of the sad and ugly cracked pavements.