16 Sep 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Netherlands, News and features

Journalist Richeron Balentien woke up one night to find his car had been torched (Photo: Richeron Balentien)

It’s a Wednesday morning in May 2014, around 3am and still dark outside. Radio journalist Richeron Balentien, his girlfriend and their 2-year-old daughter are sound asleep until the smell of fire wakes them up. When they look out of the window they see Balentien’s car burning in the yard in front of the house. He immediately knows what is going on.

“It was a clear threat,” Balentien told Index on Censorship over the phone. “It was a warning, to shut me up.” The police confirmed the car was purposely set alight. The perpetrator has not been brought to justice.

The Netherlands is always found near the top of press freedom rankings, this year second only to Finland in the Reporters Without Border’s Press Freedom Index. But rarely taken into account, however, are the Dutch islands in the Caribbean sea. The largest of these, Curacao, became a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010.

If Curacao was included in the Netherlands’ press freedom score, it might not place so high on the list. Journalists like Balentien face threats and attacks, as they fight a lonely and dangerous battle to get the truth about corruption and organised crime on the island out.

The attack on Balentien’s car happened just a few hours after Gerrit Schotte, the first prime minister of an autonomous Curacao, was arrested on allegations of money laundering and forgery during his time on power. He was released after a week in custody, but the investigation is ongoing.

Balentien aired the news on his radio station Radio Direct, while many other media outlets kept silent. “This is a small island,” he said. “Everybody knows each other. Most journalists don’t investigate. They don’t want to get into trouble”.

According to a recently published Unesco report, Curacao’s media are “not able to fulfil their role as watchdog of authorities and other powerful stakeholders in society”. It also highlights issues around journalist safety, stating that “some recent cases of harassment of journalists have caused public debate on the issue of safety and are reason for concern”.

The report concludes that social and political pressures lead to self censorship among the press, as “dependency on good relationships with sources of information on one hand and protection of relatives on the other hand is very much a threat”.

In May 2013 the island was shocked by a political murder. Helmin Wiels, a popular politician determined to rid the island of high level corruption, was shot dead by an assassin in broad daylight.

The atmosphere on the island has been tense ever since, Balentien said. “Nobody thought it was possible that someone of that calibre could get killed. It shocked the entire island,” he explained. “The atmosphere changed. Everyone is afraid.”

Two men were sentenced to life in prison for killing Wiels, but it’s still unclear who gave the orders. Many believe they came from high up. There has been speculation that former Prime Minister Schotte knew about the plan, said Balentien — something Schotte himself denies. Wiels had accused the state telecommunications company of involvement in illegal sales of lottery tickets.

The Wiels case is one of Balentien’s ongoing investigations. “I feel everything is being done to keep the truth about this murder behind closed doors,” he said. “We need to know who gave the orders.”

A 2013 Transparency International study shows “a general lack of trust in key institutions” in Curacao. The anti-corruption watchdog labels this “a major obstacle” which will “limit the success of any programme addressing corruption and promoting good governance”. As for the media, the report highlights the lack of trained journalists, with content open to influence by the private financiers and advertisers on which “many media companies are heavily dependent”. Few requirements to ensure the integrity of media employees also “undermines the independence and accountability of the media,” according to the group.

Balentien is sure that former prime minister Schotte gave the order to attack his car. “Sources told me that it was discussed within the party to set my car alight to frighten me,” he said. “I have never been afraid to talk about Schotte, his party or the corruption.”

Dick Drayer, the Curacao correspondent for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS, also believes there was a political motive behind the attack. “Schotte’s party is behind this, everybody knows that,” he told Index on Censorship.

Drayer has been working as a journalist on the island for nearly ten years. “I see is an increase of intimidation towards journalists. Journalists here are taught not to ask questions. There is verbal and physical violence. When you dig in dirty business in Curacao, you know you can get into trouble. That leads to self censorship,” he said. “In Netherlands the media controls the power, in Curacao it’s the other way around.”

While the island has had its own government since 2010, ties with the Netherlands are still strong. Corruption and organised crime in Curacao are occasionally discussed in Dutch parliament and the Dutch police is involved in the Wiels murder investigation.

But “the relationship is disturbed,” according to Dryer. “The Netherlands is careful to intervene when things are going the wrong way on the islands, because they’re afraid to be seen as the coloniser.” He thinks his country could be more involved when it comes to corruption and organised crime. “They should speak up more. The Netherlands worries about human rights in China, but when it comes to Curacao they say it’s an internal matter.”

After the car incident, Balentien’s station Radio Direct continued to receive anonymous phone threats. “I am aware,” he said. “I look around. I turn to see who’s driving behind me. I check my house before I enter.”

Despite this, he maintains he will keep up his investigative reporting on high level corruption and the Wiels murder case.”Because I don’t want this island to be ruined by these people anymore”.

More reports from The Netherlands via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Bloemendaal municipality accused of censoring local newspaper

Journalists attacked during anti-ISIS protest in The Hague

Journalist on trial for defamation

Photographer assaulted by housing corporation employee

Restrictions on filming inside parliament building

This article was posted on 16 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

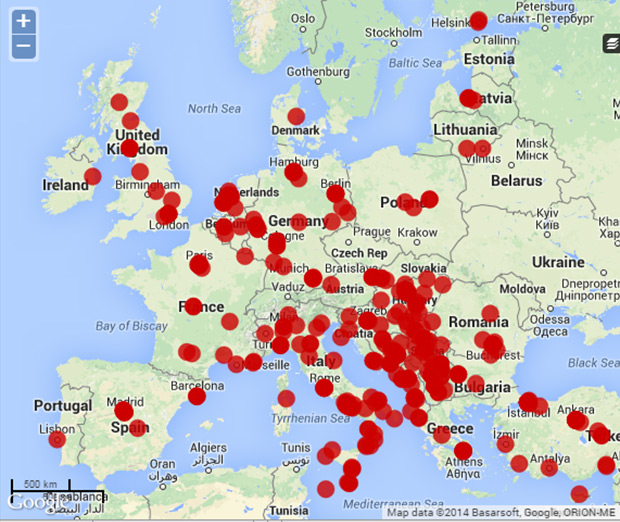

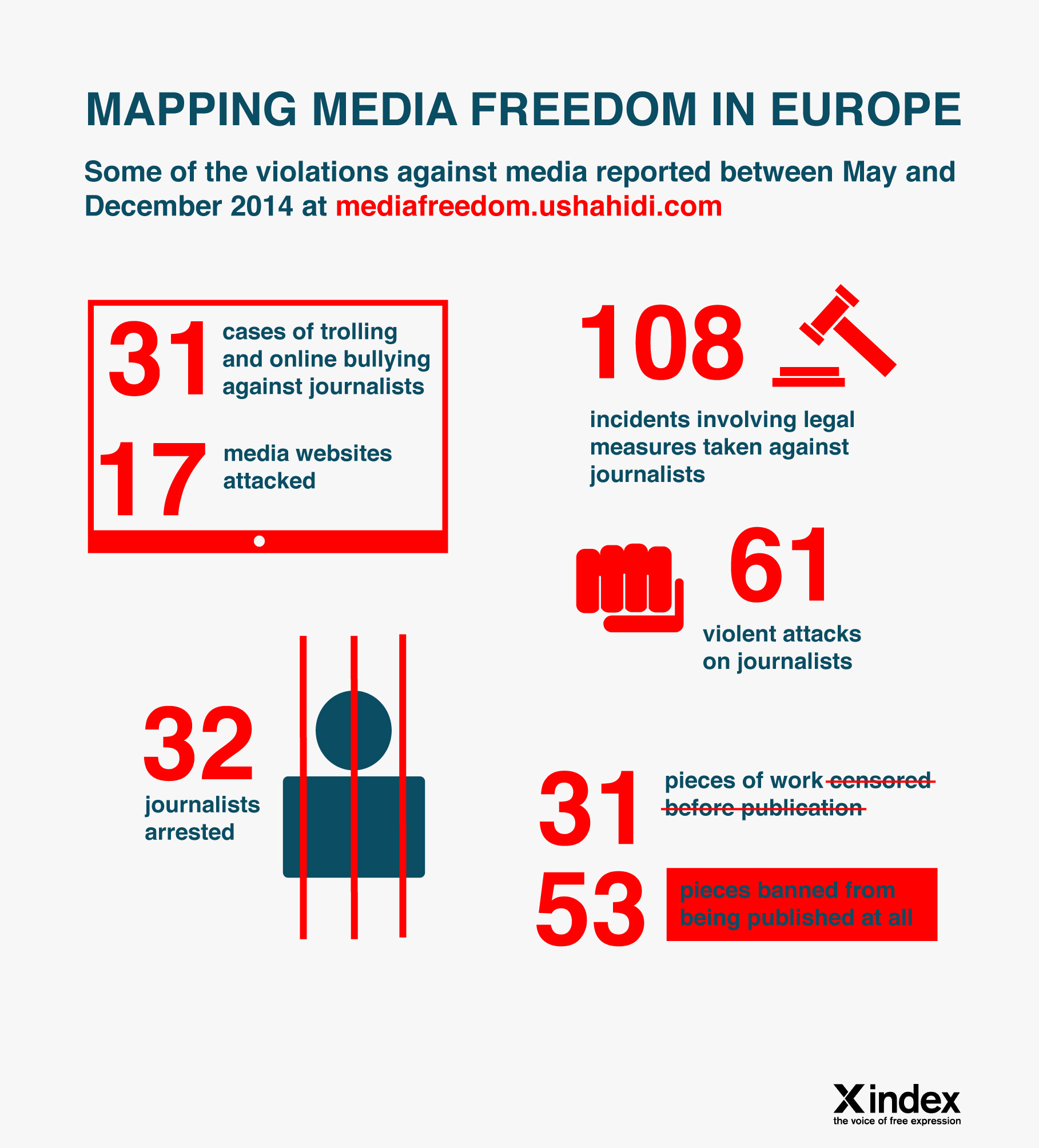

3 Jun 2014 | Campaigns, Politics and Society

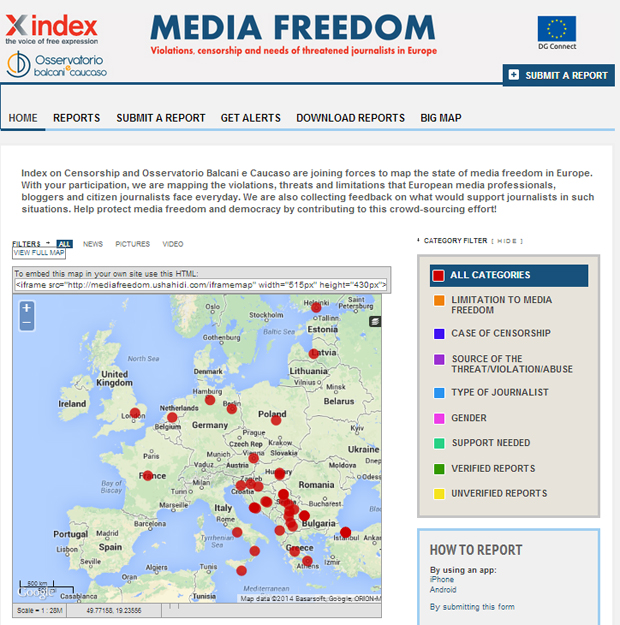

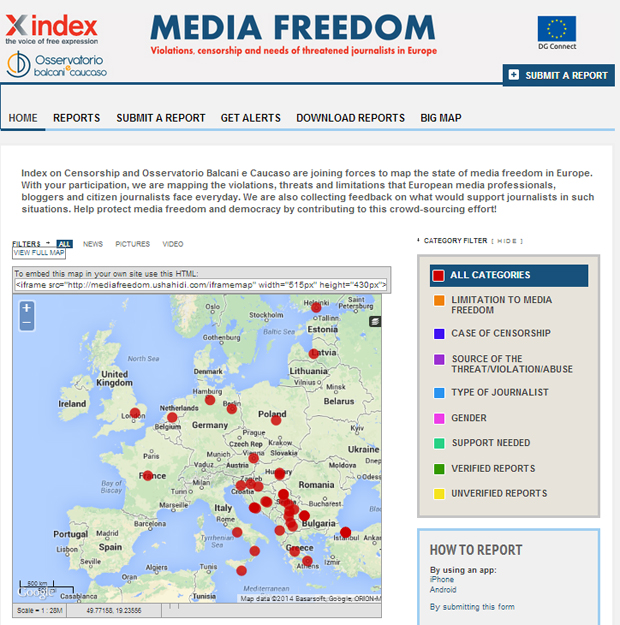

As part of its effort to map media freedom in Europe, Index on Censorship’s regional correspondents are monitoring media across the continent. Here are incidents that they have been following.

AUSTRIA

Police block journalists’ access to protest

Police denied journalists access to the site where members of the right-wing group “Die Identitären” were demonstrating on May 17. News website reports and a video from Vice News show police using excessive force against demonstrators. The Austrian Journalists’ Club described the police’s treatment of journalists as one of the recent “massive assaults of the Austrian security forces on journalists” and called for journalists to report breeches in press freedom to the club. (Austrian Journalists’ Club) (Twitter)

CROATIA

Croatian law threatens journalists

Croatia’s new Criminal Code establishes the offence of “humiliation”, a barrier to freedom of expression that has already claimed its first victim among journalists – Slavica Lukić, of newspaper Jutarnji list. A Croatian journalist is likely to end up in court and be sentenced for “humiliation” for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek, Croatia’s fourth largest city, is accused by the judiciary of having received a bribe of 2,000 Euros to pass some students during an examination. For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news. According to Article 148 of the Criminal Code, introduced early last year, the court may sentence a journalist (or any other person that causes humiliation to others) if the information published is not considered as of public interest.

CYPRUS

Cyprus’ Health ministry Director General accused of 30million scandal whitewash

9.5.2014: The former Director General of the Ministry of Health, Christodoulos Kaisis, is alleged to have censored the responses of two ministerial departments during an audit regarding a 30 million scandal of mispricing of drugs. He did not send the requested information to the Audit Committee of the Parliament. (Politis)

DENMARK

Journalists convicted for violating law protecting personal information

On May 22 2014 two Danish journalists got convicted for violated Danish law protecting personal information because they named twelve pig farms in Denmark as sources of the spread of MRSA, a strain of drug-resistant bacteria. They argue they had been trying to investigate the spread of MRSA, but the government had wanted to keep that information secret. Their defense attorney claims revealing the names was appropriate because ‘there is public interest in openness about a growing health hazard’. The penalty was up to six months imprisonment, but the judge ruled they have to pay 5 day-fines of 500 krone (68 euro). The verdict is a ‘big step back for the freedom of press’ in Denmark, one of the journalists, Nils Mulvad said after the trial.

FINLAND

ECHR rejects journalist’s free speech claim

On April 29 2014, the European Court of Human Rights rejected a free speech claim over a defamation conviction by a Finnish journalist. In August 2006 journalist Tiina Johanna Salumaki and her editor in chief were convicted of defaming a businessman. The newspaper published a front page story, asking whether the victim of a homicide had connections with this businessman, K. U. The court ruled that Salumaki and the newspaper had to pay damages and costs to K. U. According to Salumaki her right to free expression was breached.

GERMANY

Journalist’s phone tapped by state police

A journalist’s telephone conversation with a source was tapped by state criminal police. The journalist, Marie Delhaes, spoke about the police’s subsequent contact with her on the media show ZAPP on German public television. Police asked her to testify as a witness in a criminal case against the source she communicated with, an Islamist accused of inciting others to fight with rebels in Syria. Delhaes was threatened with a fine of 1000 Euros if she were to refuse to testify. She has since claimed reporter’s privilege, protecting her from being forced to testify in a case she worked on as a journalist. (NDR: ZAPP)

Local court rules police confiscation of podcasters’ recording equipment and laptops was illegal

A court ruled on May 22 that police officers’ 2011 confiscation of recording equipment and laptops in a van used by the podcasters Metronaut and Radio Freies Wendland was illegal. The podcasters were covering the transport of atomic waste through Germany and were interviewing anti-atomic energy activists. When the equipment was confiscated, police officers also asked the podcasters to show official press passes, which they did not have. The court ruled that police failed to determine the present danger of the equipment in the van before confiscating it for three days. Metronaut later sued the police. (Metronaut) (Netzpolitik.org)

GREECE

Lost in translation

The Greek newswire service ANA-MPA is accused by its own Berlin correspondent of engaging in pro government propaganda after a translation of the official announcement by the German Chancellor regarding Angela Merkel’s Athens visit is ‘revised’, eliminating all mentions of ‘austerity,’ replacing the word with ‘consolidation’. (The Press Project)

Radio advert from pharmacists banned

A union representing pharmacists in Attica has accused the government of censorship, after it was told it may not broadcast adverts deemed by the authorities to be a political nature in the run up to elections later this month. (Eleftherotypia, English Edition)

ITALY

The regional Italian newspaper “L’ora della Calabria” is shut down due to political pressure

After the complaint, in February, against the pressures to not refer in an article to the son of senator Antonio Gentile, and to the block of the printing presses on the same day (an episode that is under investigation by the judiciary), now the newspaper L’Ora della Calabria is closing. The publications have been halted, even that of the website. This was decided by the liquidator of the news outlet, who had for a long time been in financial difficulties.

Reporter sued for criticizing the commissioner

Marilena Natale criticized a legal consultancy that cost €60’000 in the town whose City Council has dissolved for mafia, and which suffers from thirst due to the closure of the artesian wells. Ms Marilena Natale, reporter for the Gazzetta di Caserta and +N, a local all-news television channel, was sued. She had in the past already been the victim of other complaints and assaults. To denounce the journalist was Ms Silvana Riccio, the Prefectural Commissioner who administers the City of Casal di Principe, fired due to Camorra infiltrations. The Commissioner Riccio feels defamed by a series of articles written by the reporter in which the decision to spend €60’000 for legal advice is criticized, while the citizens suffer thirst due to the closure of numerous wells due to groundwater pollution.

MACEDONIA

A band to defend press freedom

24.4.2014: A music band called “The Reporters” was created recently by famous Macedonian journalists. The project aims to defend press freedom in Macedonia and support their colleagues who are facing censorship and other limitations. (Focus)

Macedonian government member encourages censorship in the press

14.5.2014: The Macedonian government quietly encourages censorship in the press, buys the silence of the media through government advertising and at the same time gives carte blanche to use hate speech, said Ricardo Gutierrez, Secretary General of the European Federation of Journalists during a conference of the Council of Europe in Istanbul on the 14th of May. (Focus)

Macedonian Journalists ‘Working Under Heavy Pressure’

24.3.2014: Sixty-five per cent of Macedonian journalists who responded to a survey publish last March, have experienced censorship and 53 per cent are practicing self-censorship, says the report, entitled the ‘White Book of Professional and Labour Rights of Journalists’. (Balkan Insight)

MALTA

The Nationalist Party complains of censorship by the public broadcaster PBS

The Nationalist Party (PN) has accused PBS of censoring it in its coverage of the European parlament elections campaign. The party noted that PBS did not send a journalist to report on Simon Busuttil’s visit to Attard and Co on Tuesday and it had also failed to sent a reporter to cover a press conference addressed by PN Secretary General Chris Said in Gozo this morning. “This is nothing but censorship during an electoral campaign,” the PN said. The PN has also complained with the national TV station on its choice of captions for news items carried in the bulletin.

NETHERLANDS

Press photographers’ equipment seized

During a raid on a trailer park in Zaltbommel on may 27 2014, the cameras of two press photographers were seized by the police. According to the spokesman of the court of Den Bosch the police took the cameras after several warnings. The photographers were on the public road. After a few days the two photographers got their cameras back, but their memory cards with the photo’s are still not returned. The NVJ, de Dutch journalist Union, has pledged to stand with one of the journalists in his claim to get his photo’s back.

SERBIA

Serbia Floods Interrupt Free Flow of News

Websites criticising the government’s handling of the flood disaster in Serbia have come under attack from hackers in what some call a covert act of censorship. Creators of the Serbian blog Druga Strana, which published critical posts on the Serbian state’s handling of the flooding, were forced to shut it down on Tuesday after repeat attacks on the site. “The site has been under heavy attack so we decided to shut it down in order not to compromise other sites on the server,” Nenad Milosavljevic said.

Serbian Newspaper Editor Fired After Criticising Govt

The sacking of Srdjan Skoro, editor of state-owned newspaper Vecernje Novosti, who publicly criticized Serbia’s new ministers, has been described as an attack on independent media. Skoro said that he was told that he was no longer the editor of the Serbian tabloid Vecernje Novosti on Friday morning, but was given no explanation for his sacking. “I have been told to find another job and that I would perhaps do better there,” Skoro said. He said that although no one has said it directly, the reason for his dismissal was his recent appearance on public service broadcaster RTS’s morning TV show, in which he openly criticised some candidates for posts in the new Serbian cabinet.

SERBIA

Media in Serbia: the government’s double standard

Aleksandar Vučić’s government seems to be adopting a double standard when it comes to media: one for the EU, one for Serbia, with tight control over newspapers and television stations. I do not believe in chance, and I know “where all this is coming from and who is behind it”. Thus Aleksandar Vučić, Prime Minister of Serbia, commented the statement by Michael Davenport, head of the EU Delegation, about “unpleasant and unacceptable” issues in Serbian media. Davenport said that elements of investigations conducted by the judiciary are leaked to the public through some media, and that the “cases” of parallels being made between representatives of civil society and crime are “a clear violation of the ethical standards of the media”.

SLOVENIA

If you can’t stand the heat, don’t turn up the oven: Strasbourg Court expands tolerance for criticism of xenophobia to criticism of homophobia

On the 17th of April 2014, the European Court of Human Rights issued a judgement in the case of Mladina v. Slovenia. In this case, the Court further develops its standing case law on “public statements susceptible to criticism”. When assessing defamation cases, the Court has in the past found that authors of such statements should show greater resilience when offensive statements are in turn addressed to them.

SPAIN

The government threats to censor social media

“We have to combat cybercrime and promote cybersecurity, and to clean up undesirable social media.” These were the words of the Spanish Minister of Interior, Jorge Fenández Díaz, after the wave of comments published on social media about the assassination of Isabel Carrasco, president of the Province of León and member of the government party (Pp). Although the majority expressed their condolences to the family of the victim, there were some that took advantage of the moment to openly criticize the politician, including mocking her assassination. These tweets generated a strong reaction of rejection in certain circles. For their part, Tweeters have reacted by creating two hashtags, #TuiteaParaEvitarElTalego (Tweet to stay out of Jail) y #LaCárcelDeTwitter [Twitter Prison], through which many Internet-users vent their frustration against politicians who want to silence them. On the other hand the Federal Union of Police has published a note that proposes a change in legislation with the alleged intent of protecting minors, relatives of victims, and users in general.

Extremadura public television don’t broadcast the motion of censure on the regional president Monago

Extremadura public television did not broadcast the debate and subsequent vote of no confidence on the regional president and member of the government party Antonio Monago on May 14th, despite the political relevance of the issue (the debate was broadcasted only trough the TV’s website). The workers called a protest to consider a motion of censure “is a matter of highest public interest and should be covered by public broadcast media in all its channels”, as expressed by the council in a statement.

TURKEY

Founder of satirical website sentenced for discussion thread considered insulting to Islam

The founder of the satirical online forum Ekşi Sözlük was given a suspended sentence of ten months in prison. Forty authors for the user-generated website were detained in connection to a complaint that a thread in an Ekşi Sözlük forum was insulting to Islam. Founder Sedat Kapanoğlu and another defendant received suspended prison sentences for insulting religious values. (Hürriyet Daily News)

Journalists recently released from prison speak out against government using release for political capital

Journalists who had been imprisoned for two years in connection to the KCK case were released this month. Several of the released journalists gave a press conference on May 13 condemning the government’s manipulation of the case to improve its own human rights and press freedom standing internationally. Yüksek Genç, a journalist who spoke at the press conference, said that the amount of journalists in prison can not be the only measure of Turkey’s press freedom, since the government has other ways of meddling in media and putting economic pressure on news organisations. A number of journalists have been released from prison this year after a court regulation was changed, enforcing a shorter maximum detention time for prisoners awaiting trial on terrorism charges. (Bianet)

Police detain and injure journalists at May 1 protests

During May Day protests in Istanbul, police blocked journalists’ access to demonstrating crowds and demanded they show official press passes to enter the area around Taksim Square. At least 12 journalists were injured by police officers using rubber bullets, teargas and bodily force. Deniz Zerin, an editor of the news website t24, was detained trying to enter his office and held for three days. (Bianet)

Prominent journalist sentenced to ten months in prison for tweet insulting Prime Minister Erdoğan

On April 28, the journalist Önder Aytaç was sentenced to ten months in prison for a 2012 tweet that the court ruled to be insulting to Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan under blasphemy laws. The tweet included a word that translates to “my chief” or “my master” (relating to Erdoğan), but included an additional letter at the end that made the word vulgar. Erdoğan sued Aytaç, who maintained that the extra letter in his tweet was a typo. (Medium)

For more reports or to make your own, please visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

With contributions from Index on Censorship regional correspondents Giuseppe Grosso, Catherine Stupp, Ilcho Cvetanoski, Christina Vasilaki, Mitra Nazar

This article was posted on June 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

VIENNA, April 30, 2014 – The European Commission’s support for projects addressing violations of media freedom and pluralism, and providing practical support to journalists, gives European Union countries reason to celebrate this year on May 3, World Press Freedom Day, media freedom watchdogs said today.

However, new research into defamation law and practice – one of four, one-year projects launched in February under a Commission-funded grant programme focusing on the 28 EU member and five candidate countries – has shed light on one big elephant in the room, the Vienna-based International Press Institute (IPI) said. Preliminary results of a study by IPI and the Center for Media and Communications Studies (CMCS) at Budapest’s Central European University reveal that criminal laws in the EU addressing libel, slander, and insult remain rife and, in many cases, contravene international and European standards.

Furthermore, as another project, “Safety Net for European Journalists”, registered, attacks on journalists continue to represent a major challenge to press freedom in Europe. Research and field work by the Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, IPI affiliate the South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO), Ossigeno per l’Informazione and Dr. Eugenia Siapera of Dublin City University have shown that journalists across Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy often face common threats and pressure, highlighting a crucial need for transnational support.

“Media freedom and pluralism can unfortunately not be taken for granted in Europe,” Neelie Kroes, vice-president of the European Commission responsible for the Digital Agenda, said. “We all, governments, NGOs, the media, and the EU institutions have a role to play in standing firmly to defend these principles, in Europe and beyond, now and tomorrow, on and off-line. I am interested to see what the outcome of the independent projects will be.”

The European Commission grant programme, the “European Centre for Press and Media Freedom”, is funding two projects in addition to IPI’s project researching the effects of defamation laws on journalism in Europe and raising awareness of the same, and the “Safety Net” project establishing a transnational support network for journalists in Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy. Index on Censorship has created a project to map media freedom violations, and the Florence-based Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), also working in conjunction with CMCS, is creating tools and networks to strengthen journalism in Europe.

The grantees’ work, combating violations of the fundamental right to press and media freedom, is intended to play a critical role in protecting both the fundamental human right of free expression, as guaranteed by Article 11 of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, as well as the media’s instrumental role in safeguarding democratic order.

Some of the grantees will also collaborate to establish an intra-European network of legal assistance for media outlets facing legal proceedings.

IPI and CMCS plan to launch a comprehensive report in early June on the status of criminal and civil defamation law in EU member and candidate countries, intended to help identify states where engagement is required most urgently. The report will evaluate each country across a number of categories, including the types of defences and punishments available and the existence of provisions shielding public officials, heads of state, or national symbols from criticism. It will also include a first-of-its-kind “perception index” to gauge the subjective effect that criminal and civil defamation proceedings have on press freedom.

Preliminary research shows that, in nearly all EU member states, libel and insult remain criminal offences punishable with imprisonment – up to five years in some cases – and that journalists continue to face prosecutions in numerous countries, particularly Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta and Portugal. While some countries have seen movement toward decriminalisation, only a small minority of states have fully abolished criminal libel and insult provisions, among them Ireland, Romania and Britain.

A key finding so far is that while national courts in many cases apply European Court of Human Rights precedents on protection of freedom of expression, few EU member states have adopted legislation that meets these standards. This is particularly true with regard to defences available to journalists in libel proceedings. In IPI’s view, the lack of modern legislation clearly establishing defences of truth, public interest, fair comment and honest opinion contributes to an atmosphere of uncertainty and potential self-censorship on matters of public interest.

Additionally, the research so far has shown that legal protections shielding public officials from scrutiny are prevalent in many countries, and that such provisions often are found in tandem with increased punishments for journalists and media outlets that publish content that could be deemed defamatory. The combination of these two instruments – present in the laws of many EU member states – significantly weakens legal safeguards that enable journalists and media outlets to perform their necessary watchdog roles. Such barriers pose undue restrictions on freedom of expression rights and the public’s right to know, as established by international and EU conventions and treaties.

Despite clear challenges, however, the research has also found several important positive movements, including the enactment of modern civil defamation legislation in Ireland in 2009 and in England and Wales in 2013, as well as the full repeal of criminal libel in those jurisdictions. The removal, for the most part, of prison sentences as a punishment for libel in Finland, new discussions among Italian lawmakers to end imprisonment for criminal defamation and the repeal of a French law punishing insults to the president all indicate a growing, if slow, willingness to tackle archaic legislation.

If you would like more information or to schedule an interview with IPI Senior Press Freedom Adviser Steven M. Ellis, please call +43 (1) 512 9011 or email [email protected].