Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From broadcasting uprisings to employing Russian spies, Radio Free Europe brings news to poorly served regions. In the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Sally Gimson looks at the station’s history and asks if it is still needed today”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Gregory Baldwin / Ikon

In Georgia, the future of Radio Free Europe, and sister station Radio Liberty, is looking precarious. This summer the Georgian government’s central broadcaster shut down two of RFE/RL’s most popular political programmes. The broadcaster said it was part of a wider restructure, but civil society organisations condemned the move and suggested the station wanted to eliminate critical viewpoints. The move and the subsequent outcry highlight the role RFE continues to play, namely to often act as a platform for free expression in parts of Europe where these values are strained.

Radio Free Europe and Russian station Radio Liberty, which it merged with, have been broadcasting to eastern Europe and Russia since 1950. While its remit originally was to fight communism, it now states its function as serving the cause of democracy more generally.

Today in Chechnya, for example, RFE is the only station where you will hear reports from journalists and stringers in the Chechen language about the influence of Isis and the persecution of gay people. It is the only Western international station operating in Moldova, even if it broadcasts for only a few hours a day. In Armenia, its TV provides a counterbalance to government-controlled media, as well as broadcasting to the wider diaspora. And in Kazakhstan, it provided special coverage of the early parliamentary election last year with six hours of live-streamed video on its website.

John O’Sullivan, executive editor of RFE between 2008 and 2012, argues passionately that “the radios”, as he calls the stations, have key roles to play in making sure people have a strong source of news and hear different viewpoints, and in holding governments to account with local journalists reporting on the ground.

“At the moment, there is a moral war between all these countries and the argument that commercial stations can do this job is fine, except they can’t do the job of the radios,” he told Index. “CNN is … never going to have a lot of correspondents in Armenia and never going to have correspondents in Chechnya. It’s going to be doing a story once every three months. Those audiences need it every day.”

Originally set up as an intelligence services-led project, RFE aimed to counter what the US government saw as superior propaganda coming out of the Soviet Union. Although primarily funded by the CIA, it was promoted to the US public as a project for truth and freedom to which they should contribute. Future US president Ronald Reagan, a young actor in the early 1950s, fronted up the public service advertisement, encouraging donations with the exhortation: “This station daily pierces the Iron Curtain with the truth, answering the lies of the Kremlin and bringing a message of hope to millions trapped behind the Iron Curtain.”

Victoria Phillips, who runs the RFE research project at Columbia University, told Index: “These men [who founded RFE] … really did believe in the power of truth and freedom of ideas, and when I read about some of those people, you don’t like the fact that they tried to invade places, and they had coups, but in the end the core was a belief in the power of ideas, and if ideas are allowed to vent then good will take place…”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”RFE was accused of encouraging insurgents to believe the USA would intervene on their behalf militarily” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]In the beginning, the broadcasts used émigrés and dissidents for their programmes. They spoke from the headquarters in Munich to their countrymen and women in their own languages and were broadcast on short wave radios, which were widely accessible. It was an alternative source of news to the official Soviet broadcasters.

During the Cold War RFE was also a hotbed of spies, double agents and political resistance. The Bulgarian novelist and playwright Georgi Markov was assassinated in London with the tip of a poisoned umbrella in part because of his RFE In Absentia programme. Markov had dined with the communist elite and knew all about their lives. He revelled in satirising them and the absurdity of the system for his audience back home. According to the communist government he “insolently mocked” the regime and “encouraged dissidence”.

When O’Sullivan was executive director RFE/RL, he remembers the Iranian secret service taking pictures of the Iranian journalists coming into the offices, then in Prague, in an effort to intimidate them. “We know in a general way that some of the countries had agents embedded in the service which broadcast to them. We didn’t know who they were obviously. And in one particular case, in the Russian service, [there was] a man who had defected [back to Russia]. He had been in RFE during the Cold War and he defected and went to work for Radio Moscow and he subsequently wrote a tell-all memoir in which he had to confess that journalistic standards in Radio Moscow were well below the standards in Radio Free Europe, or in his case Radio Liberty.”

Later, RFE played an instrumental role in the fall of the USSR. As writer Irena Maryniak explained in an article for Index in 2010: “Western radios became a forum for dissenting views and personalities: people like Václav Havel (later president of the Czech Republic); the Russian physicist and civil rights activist Andrei Sakharov; the Polish historian Adam Michnik; or indeed maverick party members like Boris Yeltsin, who broadcast on Radio Liberty when he was out of favour with colleagues at home.”

Today, many of the 23 countries where RFE works are areas where the USA still wants foreign policy influence. It broadcasts across a huge range of media, not just radio. And the languages and countries the station covers, from the Caucasus and the Balkans to Afghanistan via Iran and Pakistan, read like a map of East-West tension.

Indeed, the congressionally funded Broadcasting Board of Governors, which has openly funded RFE since the 1970s and pours $117 million of taxpayers’ money into the service, is robust about its “soft power” intentions. Its 2016 budget report contains headings such as Countering a Revanchist Russia. And the report explicitly links broadcasting with foreign policy priorities.

So can we trust its journalism? The answer from O’Sullivan is yes. It’s not constrained to put the US view in the same way as Voice of America, and it actively seeks to encourage free speech and news coverage in countries where this is underdeveloped or difficult. Indeed, many reporters risk their lives to report for RFE, such as Khadija Ismayilova, who was imprisoned in Azerbaijan for exposing the president’s link to corruption. She was awarded the Unesco/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize in 2016 for her fearless work for the station. The station also won two prizes at the New York Festivals’ International Awards this spring, including one for the Kyrgyz service’s short video feature A Snowy Trek on Horseback to Teach School.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The people who were broadcasting suddenly realised that there were huge ramifications if you promised, or seemed to promise, something and it didn’t come true.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]There have been darker moments at RFE, the most famous being its reporting on the Hungarian uprising of 1956 when at least 2,500 people were killed and many more were forced into exile, imprisoned and deported. RFE was accused of encouraging insurgents to believe the USA would intervene on their behalf militarily and therefore making people risk their lives unnecessarily. A couple of its programmes offered tactical military advice, and one commentary told people not to give up their weapons.

George Urban, the director of the Radio Free Europe division at the time, admitted they got it wrong. He said: “The radio was young and inexperienced. After barely five years of broadcasting, its management was still testing the instruments and boundary lines of the Cold War and was simply not up to the task of responding with clarity or finesse to its first great challenge. Hungary, its baptism of fire, cost it dear.”

As Phillips said: “The people who were broadcasting suddenly realised that there were huge ramifications if you promised, or seemed to promise, something and it didn’t come true. That people were going to die; your friends were going to die.”

Despite these controversies, RFE has survived, in part because the US Congress has continued to invest in the European operation, if on a smaller scale than during the Cold War. But O’Sullivan believes “the radios” should be given a lot more money and are needed more than ever to compete with stations like Russia Today (with a budget of about $300 million in 2016) and Al Jazeera.

“I think that people will accept there is an argument for good journalism which gives the news about their own country to people whose country would like to deprive them of it, and good journalism which sets standards to which we hope the journalists in transitioning countries will aspire and gradually achieve,” he said.

This article was updated on 1 November 2017 to include additional information.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]This article first appeared in the Autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, an award-winning, quarterly magazine dedicated to fighting for free expression and against censorship across the globe since 1972. You can subscribe here or via Exact Editions here. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011399691″][vc_custom_heading text=”Surviving Lukashenko ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011399691|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

James Kirchick looks at the climate for alternative media in the aftermath of the 2010 Belarus elections.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94267″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533431″][vc_custom_heading text=”Extolling the communist party” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533431|||”][vc_column_text]October 1982

Janis Sapiets questions whether Soviet broadcasting is partaking in censorship or responsibility to the party. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94034″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228308533503″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in retreat” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228308533503|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

Hungary’s best-known novelist writes on the craving in Eastern Europe for communication and exchanges of ideas.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Federica Mogherini and Ilham Aliyev. Credit: EEAS/CC BY

A coalition of 37 human rights NGOs has sent a letter to the EU member state heads and EU leaders ahead of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s visit to Brussels to participate in the 5th Eastern Partnership Summit on 24 November 2017. The NGOs urge the EU member state heads and leaders to use the summit to call on president Aliyev to end the current human rights crackdown in Azerbaijan and commit to concrete steps in this regard, including the release of individuals imprisoned on politically motivated charges and reforms of repressive NGO legislation.

The letter was sent on 27 October to the heads and foreign ministers of the 28 EU member states, as well as to EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini, EU Commissioner for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations Johannes Hahn, EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, European Council President Donald Tusk and European Parliament President Antonio Tajani. The letter (as addressed to Federica Mogherini) can be read below or downloaded here.

Subject: Human Rights in Azerbaijan on the eve of the Eastern Partnership Summit

Brussels, 27 October 2017

Dear Ms Federica Mogherini,

We, the undersigned organisations, are writing ahead of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s visit to Brussels to participate in the 5th Eastern Partnership Summit on 24 November. We urge you to use any opportunity you will have during the summit to call on president Aliyev to end the human rights crackdown and commit to concrete and sustainable human rights reforms in Azerbaijan. These include releasing individuals imprisoned on bogus, politically motivated charges; and reforming legislation that effectively prevents independent non-governmental organisations from operating and accessing funding.

Among the 20 Deliverables for the Eastern Partnership by 2020, the European Union has, notably, identified a vibrant civil society as a pre-requisite for “democratic, stable, prosperous and resilient communities and nations.”

Yet in recent years, the Azerbaijani government’s actions sharply contradict the latter and the spirit of this important Eastern Partnership commitment. Azerbaijan has adopted and enforced laws and regulations that severely restrict, rather than foster, a vibrant civil society. It has eliminated independent media, heavily filtered internet, and imprisoned and otherwise sought to silence independent journalists, civic and political activists who are essential to any kind of civil society envisaged by the Eastern Partnership.

The government’s continued crackdown on civil society and independent media has coincided with negotiations on the new, enhanced bilateral agreement between the EU and Azerbaijan. We firmly believe that the pace of those negotiations should largely depend on the progress Azerbaijan is willing to make in respect for fundamental rights.

Although in 2016 the government released 17 unjustly imprisoned human rights defenders and government critics, their convictions stand, and some face travel restrictions and are unable to do their work without undue government interference; those released on suspended sentences could also be sent back to prison. The authorities continue to use bogus, tax-related, and other politically motivated criminal charges to jail critical journalists and bloggers; at least 11 of them are currently in prison.

Azerbaijan is ranked 162nd out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 World Freedom Index. In May 2017, unidentified people abducted journalist Afgan Mukhtarli in neighbouring Georgia and illegally brought him to Azerbaijan, where the authorities pressed bogus criminal charges against him. In August, the authorities launched an investigation against Azerbaijan’s last remaining independent news agency, Turan, and a criminal case against its founder and chief editor, Mehman Aliyev, who is now under house arrest on trumped-up tax evasion and other charges. In May 2017, authorities blocked the websites of Azadliq, the newspaper of one of Azerbaijan’s main opposition parties, and of three news outlets that have to operate from abroad: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) Azerbaijan Service, Meydan TV, and Azerbaycan Saati. In March, a court sentenced Mehman Huseynov, the chairman of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), and well-known anti-corruption blogger, to two years in prison for allegedly defaming the staff of a police station. Huseynov had publicized how several police officers arbitrarily detained and beat him, and used electric shock against him in January.

Many government critics or political opposition activists remain behind bars. Among them is Ilgar Mammadov, the leader of a pro-democracy opposition movement who in 2013 tried to run for president and who has been in prison since his arrest in early 2013 on fabricated charges of inciting violent protests. The government has ignored a judgment of the European Court of Human Rights and defied nearly a dozen resolutions by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe calling for Ilgar Mammadov’s release. On 25 October, the Committee took the unprecedented decision and triggered the infringement proceedings against Azerbaijan, provided by Article 46 § 4 of the European Convention, following its failure to implement the Court’s judgment on Mammadov’s case. The proceedings could eventually lead to the Council of Europe sanctioning Azerbaijan, for example by suspending its voting rights in the Parliamentary Assembly.

Non-governmental organisations in Azerbaijan face serious obstacles to operating due to laws and regulations that require both donors and grantees to separately obtain government approval for every grant under consideration. The government has used broad discretion to deny this approval, and the authorities have convicted and imprisoned NGO leaders who failed to obtain it.

In January 2017, the Cabinet of Ministers slightly simplified the procedure by which non-governmental groups must register their funding, but this has not reduced the discretion the authorities have to arbitrarily deny funding approval.

Since 2015, Azerbaijan’s status in two international initiatives has been downgraded due to the government’s failure to meet specific commitments to foster civil society. These include suspension of Azerbaijan’s status by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which promotes revenue transparency in the gas, oil, and mining industries, and downgrading to ‘inactive’ status by the Open Government Partnership, a voluntary initiative promoting government transparency and accountability.

In October 2017, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted two strongly worded resolutions on Azerbaijan, urging the government to cease its unrelenting crackdown against critics.

At a time when the Azerbaijani government’s defiance of its civil-society commitments has prompted two standards-based organisations to downgrade Azerbaijan’s status, and has driven the Council of Europe member states to take unprecedented collective action on Azerbaijan’s blatant breach of the European Convention, the European Union appears eager to conclude a partnership agreement with the government.

The European Union is a values-based institution. While it has common interests with Azerbaijan, shared interests without shared values will not lead to a strong and reliable partnership. Instead, it is likely to lead to a situation in which Azerbaijan believes European values are negotiable. This risk is illustrated by recent investigations by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project revealing that members of Azerbaijan’s political elite were engaged in establishing and making use of a money laundering scheme and slush fund amounting to USD 2.9 billion, some of which was used to attempt to influence several European politicians to, among other things, whitewash Azerbaijan’s human rights record.

Under these circumstances, it is of the utmost importance that the EU leaders convey the message to President Aliyev that the conclusion of any new agreement between Azerbaijan and the EU, as well as the quality of the EU-Azerbaijan relationship, depends on the Azerbaijani government’s steps to address the EU’s human rights concerns. The EU would send the wrong political message to the Azerbaijani and other governments if it fails to bring meaningful political consequences for the continued detention of critics, human rights defenders and media professionals.

We urge the heads of the EU member states and the EU to abide by the obligations under article 21 of the Lisbon Treaty, as well as the commitments spelled out in the EU’s Strategic Framework for Human Rights and Democracy to “[…] promote human rights in all areas of its external action without exception”. In the most recent Foreign Affairs Council conclusions, the EU and its member states committed to “promoting stronger positions on civic freedoms and against any reduction in the space for civil society to act.”

During your meeting with President Aliyev, at the Eastern Partnership Summit, we urge you to insist on:

The Immediate and unconditional release of Ilgar Mammadov and the prompt and unconditional release of all other wrongfully imprisoned human rights defenders and civil society and political activists who were prosecuted in retaliation for their legitimate activities.

Absolute respect for free speech and media freedoms, including the prompt and unconditional release of all journalists and social media activists wrongfully put in detention; the dropping of all charges against Mehman Aliyev, and an end to the investigation against Turan.

An immediate end to the use of travel bans to arbitrarily restrict freedom of movement and professional activity, including in respect of investigative journalist Khadija Ismaiylova, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev, and others.

Reform of laws and regulations on nongovernmental organisations and their access to foreign funding, in accordance with the Venice Commission recommendations.

We thank you for your attention to this important matter.

Signatory organisations:

1. Amnesty International

2. ARTICLE 19

3. Austrian Helsinki Association – For Human Rights and International Dialogue

4. Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House

5. Bir Duino

6. Center for Civil Liberties

7. Center for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights

8. Civil Rights Defenders

9. Crude Accountability

10. FIDH, International Federation for Human Rights

11. Freedom Files

12. Freedom House

13. Front Line Defenders

14. Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

15. Human Rights Center “Viasna”

16. Human Rights Center of Republic of Azerbaijan (HRCA)

17. Human Rights Club

18. Human Rights Monitoring Institute

19. Human Rights Watch

20. Index on Censorship

21. Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS)

22. International Media Support (IMS)

23. International Partnership for Human Rights

24. Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

25. KRF Public Alternative

26. Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights (Germany/Switzerland)

27. Macedonian Helsinki Committee

28. Moscow Helsinki Group

29. Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI)

30. Netherlands Helsinki Committee

31. Norwegian Helsinki Committee

32. OMCT – World Organisation Against Torture

33. PEN International

34. Public Association “Dignity”

35. Public Verdict Foundation

36. Regional Center for Strategic Studies

37. Reporters Without Borders

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

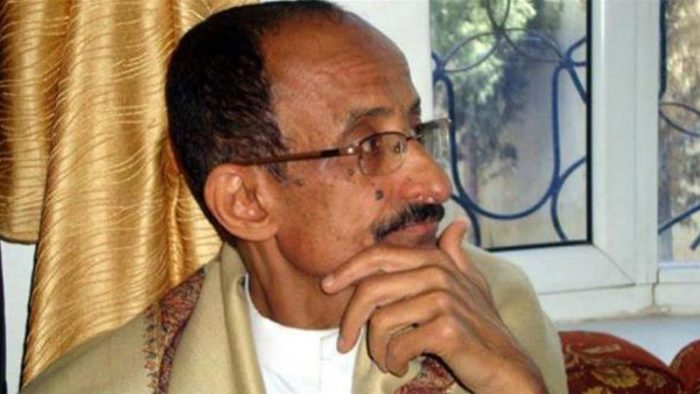

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Interpol 86th general assembly (Credit: Interpol)

Red notices have become a tool of political abuse by oppressive regimes. Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

“The use of the Interpol system to target journalists is a serious breach of media freedom. Interpol’s own constitution bars it from interventions that are political in nature. In all of these cases, the accusations against the journalists are politically motivated,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

In the most recent case on 21 October, journalist and blogger Zhanara Akhmet from Kazakhstan was detained in Ukraine on an Interpol warrant and is currently in a temporary detention facility. Akhmet claims this red notice is politically motivated.

The journalist worked for an opposition newspaper, the Tribune, in Kazakhstan as well as documented human rights violations by the Kazakh authorities on a blog.

On 14 October, also in Ukraine, Azerbaijani opposition journalist Fikret Huseynli was detained at Kyiv Boryspil Airport.

Huseynli sought refuge in the Netherlands in 2006 and was granted citizenship two years ago. While leaving Ukraine, the journalist was stopped by Interpol police with a red notice issued at the request of the Azerbaijani authorities. He has been charged with fraud and illegal border crossing.

Because Huseynli holds a Dutch passport, he cannot be forcibly extradited to Azerbaijan, but he told colleagues he fears attempts to abduct him.

“The arrest of the Azerbaijani opposition journalist by the Ukrainian authorities at the request of the authoritarian government of Azerbaijan is a serious blow to the common European values such as protection of freedom of expression, which Ukraine has committed itself to respect as part of its membership in the Council of Europe and the OSCE,” IRFS CEO Emin Huseynov said.

On 17 October, Boryspil City District Court ruled to imprison Huseynli for 18 days at a pre-trial detention centre, Huseynli’s lawyer announced.

Huseynli’s arrest was the second time in a month that a journalist has been detained in Ukraine on a red notice.

On 20 September, authorities detained journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov, who had been seeking political asylum in Ukraine, under an Interpol red notice when he arrived from Turkey with his family. Okhunjonov writes from exile for sites including BBC Uzbek on Uzbekistan’s authoritarian government. Uzbekistan filed the international arrest warrant for the journalist on fraud charges. He denies the charges against him.

Five days after he was detained, a Kyiv court sentenced Okhunjonov to a 40-day detention while they decide whether to extradite him to his home country. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F%23%2F|||”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Interpol warrants have also been issued in Spain.

Turkish journalist Doğan Akhanlı was detained while on vacation in Spain on 9 August. The journalist has lived in Cologne since 1992 where he writes about human rights issues, particularly the Armenian Genocide, which Turkey denies.

Turkey charged Akhanlı with armed robbery which supposedly occurred in 1989. After the charges were brought against him in 2010 and he was acquitted in 2011, the Supreme Court of Appeals overturned his acquittal and a re-trial began. Akhanlı faces “life without parole”.

Two weeks later, Interpol removed the warrant and Akhanlı was released. The decision was made after German chancellor Angela Merkel denounced the abuse of the Interpol police agency: “It is not right and I’m very glad that Spain has now released him. We must not misuse international organisations like Interpol for such purposes.”

Markel claimed Erdogan’s use of the international agency for political purposes was “unacceptable”.

Akhanlı’s detention came two weeks after Turkish journalist Hamza Yalçın was detained on 3 August at El Prat airport in Barcelona, where he was vacationing, Cumhuriyet reported. He holds a Swedish passport and has sought asylum there since 1984.

Yalçın is being accused of “insulting the Turkish president” and spreading “terror propaganda” for Odak magazine of which he was the chief columnist, according to a report by Evrensel.

Like Ukraine, Spain’s member state status in the Council of Europe also arises the question of their activity in the arrests of Akhanlı and Yalçın. “The latest cases of arrests of journalists in Ukraine and Spain on the basis of Interpol red notices … have extremely worrying implications for press freedom,” Rebecca Vincent UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders, said. “Interpol reform is long overdue, and is becoming increasingly urgent as critical journalists are now at risk travelling even in Council of Europe member states”.

Turkey’s recent continued persecution of journalists through Interpol also reached as far as Germany. A Turkish prosecutor has requested the Turkish government issue a red notice through Interpol though it is unclear if it went through.

On 28 September 2017, the Diyarbakir Prosecutor’s Office filed an application to seek an Interpol red notice for Can Dündar, the former Editor-in-chief of Turkey’s anti-regime newspaper, Cumhuriyet. The demand for a red notice is based on a speech made by Dündar in April 2016, supposedly supporting the “terror propaganda” of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Dündar fled Turkey for Germany in 2016.

On the same day, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) nominated Dündar and the Cumhuriyet newspaper for the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Turkey is no exception to using this system just as is Russia, Iran, Syria, and its close neighbour and ally Azerbaijan among other governments, where political direction does not necessarily align with democracy, respect for human rights and basic freedoms,” Arzu Geybulla, an Azerbaijani journalist and human rights activist said. “Targeting its citizens who have escaped persecution and have been forced to flee as a result of their opinions, is a worrying sign especially at a time, when over 160 journalists are currently behind bars in Turkey and thousands of people have lost their jobs, been arrested or currently face trials in the aftermath of the July coup.”

Although PACE has adopted a resolution condemning the abuses of Interpol red notices, a review of Interpol’s red notice procedure has yet to be adopted. Amid criticism from human rights activists, journalists, and even leaders like Angela Merkel, it is unclear if Interpol will make a change to their red notice regulations.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1509034712367-374920af-c5df-6″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]