Index denounces Iran’s Shah

As part of a special report on Iran, Index is one of the first magazines to denounce the Shah.

As part of a special report on Iran, Index is one of the first magazines to denounce the Shah.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”108837″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]On 24 August 2019 Kioomars Marzban, a 27-year-old satirical writer from Iran, was sentenced to 23 years and 3 months in prison. He was found guilty on five separate charges, given a two-year travel ban, and a two-year ban on publishing or using social media.

Marzban left Iran in 2009 and had been living in Malaysia for nearly a decade, from where he wrote for Iranian diaspora programmes, including Radio Farda and the London-based media network Manoto. He returned to Iran to spend time with his sick grandmother in early 2018. On his return, he began leading creative writing workshops and had referred to some of his work abroad.

In early September 2018, authorities arrested Marzban on charges relating to his satirical writing. They raided his house and confiscated his laptop, mobile phone, and writing materials. He was only permitted to appoint a lawyer several months after being detained.

Following his arrest, a website affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) falsely claimed that Marzban had travelled to the United States in order to set up an anti-Iranian media outlet. The website said that the outlet would have been “aimed at inflaming the people and creating social divisions”. Marzban is understood to have only ever travelled to Georgia (in the Caucasus) during his time in Malaysia.

The IRGC also accused Marzban of cooperating with the human rights organisation Freedom House, which according to them is “a project of American intelligence to push the issue of human rights internationally through media organisations”.

Marzban was sentenced to 11 years for “communicating with America’s hostile government”, 7 years and 6 months for “insulting the sacred”, 3 years for “insulting the [supreme] leader”, 1 year and 6 months for “propaganda against the state”, and 9 months for “insulting officials”.

Condemning the sentencing of Kioomars Marzban, Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive of Index on Censorship, said “Kioomars has been given a sentence that would put him in jail for almost as long as he has been alive, meaning he would not be freed until 50. And all because he poked fun at power through writing. We urge satirists worldwide to condemn his jailing and for states who claim to support freedom of expression to demand his immediate release ”.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567097330224-5056a739-f424-9″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Forty years ago, on 11 February 1979, the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, came to an end after millions of Iranians, from all backgrounds, took to the streets in protest at what they saw as an authoritarian, oppressive and lavish reign.

After decades of royal rule, and following 10 days of open revolt since the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to the country after 14 years of exile, Iran’s military stood down. With Pahlavi forced to leave the country, the Islamic Republic of Iran was declared in April 1979.

Here Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the revolution, an event that has since shaped the entire Middle East and has had a lasting impact to this day.

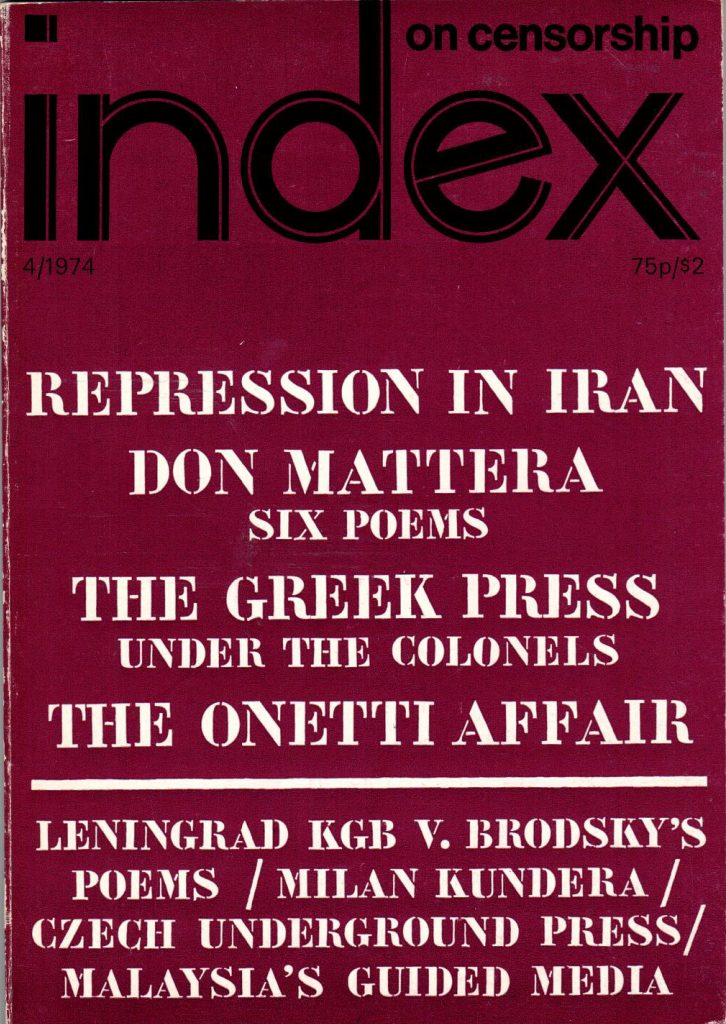

Repression in Iran , the Winter 1974 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Ahmad Faroughy

December 1974, vol. 3, issue 4

In October 1972, the shah of Iran celebrated the 2,500th year of Persian Monarchy which, despite twenty national dynastic changes, has constantly endeavoured to remain Absolute. Although the aim of this article is not to debate the political merits and demerits of autocracy as a means of government, it is obvious that whatever minor benefits Iran may have derived from hereditary dictatorship, freedom of expression is certainly not one of them.

China: Unofficial texts, the September 1979 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

M. Siamand

September 1979, vol. 8, issue 5

The Muslim clerical establishment had not been decimated, and the various peoples of Iran, showing a remarkable unanimity, rallied behind the exiled Ayatollah to overwhelm the imperial army into submission by staring it In the face. What the great majority of observers regarded as impossible has come to be: the minority cultures seem no longer in danger of quick extinction, and everyone is engaged in an exhilarating debate about the future. But unfortunately, threatening clouds can be seen gathering on the horizon. The revolution has not yet started to devour its own children, yet some powerful men in the new hierarchy are already saying that it might have to do so: secular, democratic opponents of the former regime are denounced as counter-revolutionaries, most clergymen seem determined to turn Iran into an intolerant theocracy and a cultural backwater, and martyrdom for Islam is held up for the young as the highest achievement they should aim at.

The rebirth of Chilean cinema in exile, the April 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Edward Mortimer

April 1980, vol. 9, issue 2

An extraordinary exhilaration gripped the Iranian people as the revolution at last triumphed and the remnants of the imperial regime suddenly crumbled away. One returns to confront the irritation of a European intelligentsia which is at once alarmed by the possible consequences of the Iranian revolution and perplexed by the fact that it does not quite fit into any of the ideological pigeon-holes which Western thought had prepared for it; and one is expected to atone by taking responsibility for the events which follow it.

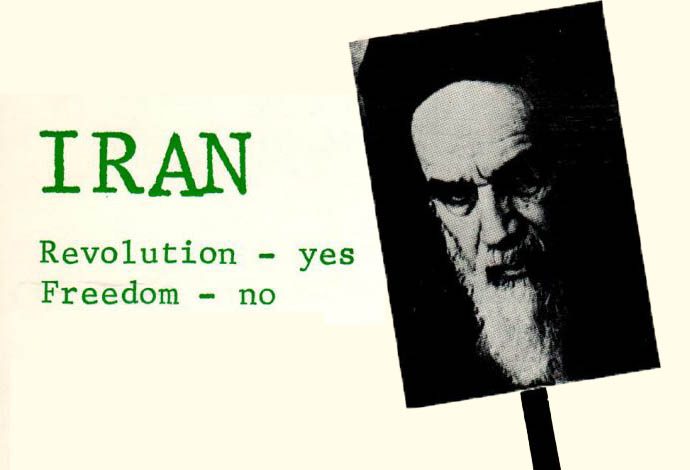

Iran: Revolution – yes, Freedom – no, the June 1981 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Leila Saeed

June 1981, vol. 10, issue 3

Concern for the restoration of social justice, for basic human rights, as well as national independence, provided the fundamental motive for the formidable mass movement which brought down the Pahlavi dynasty in February 1979. Iranians of different social backgrounds, ethnic and religious groups, of different creeds and ideologies came together in their revolt against the oppressive and arbitrary regime. And it was religion which provided the formal channels and the leadership by means of which the opposition expressed its demands and conducted its struggle.

Writers and Apartheid, the June 1983 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Islamic attack on Iranian culture

Amir Taheri

June 1983, vol. 12, issue 3

Book-burning did not become an Islamic tradition. On the contrary. The Bedouin’s enchantment in front of the written word soon prevailed over the Caliph’s ‘ impulsive outburst. Islam expanded and developed into an established religion with universal appeal, and became an accidental heir to the wisdom of the classical world which it later passed on to the West. In 1979, in the triumph of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, an echo of Omar was heard. In their hatred of the “corrupt” contemporary world, Iran’s mullahs, who had designed and led the revolution, tried to “return to the source” and recreate the early Islamic society as they imagined it. An important step in that direction was what the revolution’s Supreme Guide, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, described as “deculturisation”.

Samuel Beckett: Catastrophe, the January 1984 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

February 1984, vol. 13, issue 1

Censorship was planned by the regime of the Islamic Republic even before the February 1979 revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic oligarchy to power. This particular kind of censorship may not be without precedent in history, but it must certainly be rare. There were attacks on coffee-houses, restaurants and other public places by men armed with clubs and stones; unveiled women were harassed; slogans of the opposition were cleaned from the walls; banks, cinemas and theatres were burned. None of this seemed to follow any specific plan, but nonetheless it just kept on happening. Men with angry faces, dressed in shabby clothes, would be seen lurking in corners; they would come out for a moment of sudden violence and then disappear again. An astute observer might have called those attacks wounds on the body of the revolution as it was in the process of taking shape, but not many people noticed, and consequently they saw this deranged behaviour simply as a sign of revolutionary anger and class hatred.

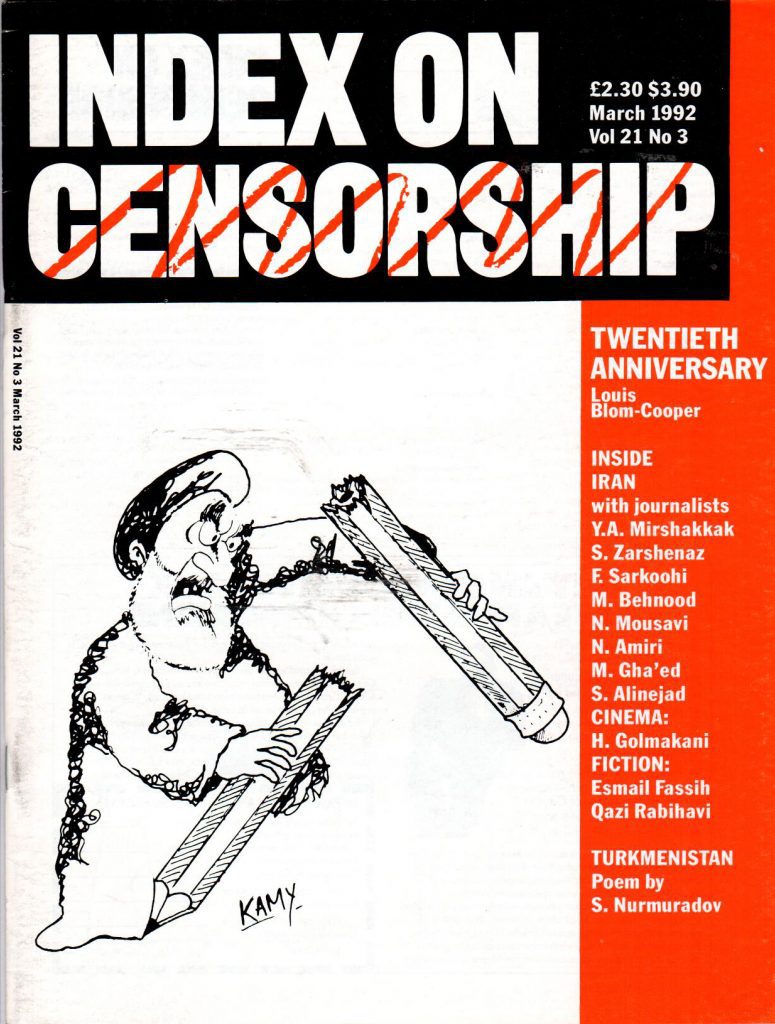

20th Anniversary: Freedom and responsibility, the March 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

March 1992, vol. 21, issue 3

Index brings together opposing views on the nature of human rights, freedom of expression and democracy within the Islamic Republic of Iran. This unique confrontation, first presented on 14 December 1991 on the UK’s independent Channel 4 TV programme South, reveals the gulf that separates the ‘universal’ principles of the Western Christian/humanist tradition from the theocentric teachings of Islam on the same matters. Even within Iran, the battle between rival and opposing interpretations of Koranic teaching on these subjects reaches into the highest levels of government.

As the Iranian journalist Enayat Azadeh, intimately connected with the film, himself says, we are not talking about anything as simple as those who are for and those who are against the Revolution. Committed supporters of the Islamic state who, influenced by education and inclination, wish to incorporate Western liberal ideas into Islamic thinking on, for instance, freedom of expression in the media or the arts, find themselves at odds with the pure Islamists who will brook no interference with the integrity of Islam

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549892591542-afaf5ec8-5514-0″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In 2009, incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s highly contested election against Mir-Hossein Mousavi, which led to public outrage and the formation of the Green Movement, filling the streets with demonstrations calling for Ahmadinejad’s ouster. For the next two years, Iranian authorities ran a campaign of jailing journalists and political opponents. Journalist Omid Rezaee was one such detainee.

The Iranian-born mechanical engineering student was the editor-in-chief of Fanous, a student magazine which was banned for standing with the Green Movement. Rezaee was arrested in October 2011.

In 2012 he fled to Iraq, and in 2015 he made his way to Germany. In February 2017 he started his own multilingual website, Perspective Iran, where news about Iran is mainly reported in German. He has also been working as a freelance writer within German media outlets since he was exiled. Rezaee aims to show the many hidden aspects of Iran and the nature of the everyday lives of its people.

Index on Censorship: You became a journalist at a very young age. What made you choose this career path so early?

Omid Rezaee: Storytelling excites me and has done so since childhood. It’s the first thing I learned about myself. First by reading stories – whether journalistic and media stories or fiction – and then by telling stories. When I was 10, I founded a small magazine in the primary school which failed after only two editions. By 15, I founded the second one in the first year of high school. This one was published for one year and by 17 I founded the next one which was being distributed in all high schools of our town and which brought me to the attention of the authorities for the first time. But I still think this was worth all the troubles because it gave me the opportunity to narrate stories. It’s the most delightful thing in this world.

Index: Why did you leave Iran?

Omid: The idea of leaving the country popped in my mind while I was sitting alone in a cell for days and nights without being able to see or talk to anyone. I was asking myself for how much longer I can bear this situation. When I was sentenced to two years in prison, I had to think about it more seriously. There are many reasons – both private and political – which led to my decision to leave the country. I would say the most important one – which still applies – is that I missed my freedom. First and foremost the freedom of speech, but it’s also freedom of lifestyle.

Index: Walk us through your migration on foot to Iraq.

Omid: Apart from the dangers and physical and technical things, I would never ever forget the moment I crossed the border as if it was the end of the earth. I would never forget how I looked back to the soil, the ground which used to be my homeland. I guess there is a huge difference when you leave the country by a plane and don’t see that “border”. And when you cross it on foot and you know, you won’t be back soon. This grieves you deeply.

Index: You are an active writer online. How do you think the internet has changed journalism?

Omid: I’ve started a professional career online and I am now studying digital journalism. By now it’s part of me and I’m part of the digital world. Honestly, I have no clue how the professional journalism used to work before it was online. But the fact that I can still report on Iran and the Middle East, even though I’ve been away for years, is directly due to the internet and online world. Apart from all the troubles we’re facing, we are closer to each other because of the internet. And more important: the digital world gives us – the journalists – more possibilities to strive against illegitimate authorities all over the world.

Index: How have you settled into life away from home?

Omid: It’s not true if I say I don’t miss my hometown, the city I studied in and the people I loved – or still love – and who love me. But the bottom line is that home is where one is free, where one can develop himself and live with dignity. I have a lot of good memories of Iran and I deeply miss a lot of people there, but I never considered Iran as a home, and it’s the same here in Germany. My home is my language. I don’t mean Farsi; I love German just as much my mother tongue, and this applies to the English language and the languages I’m learning right now. My home is the story I’m telling and I’m settling into my new life by telling stories. I am firmly convinced that only storytelling can rescue us.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]