Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

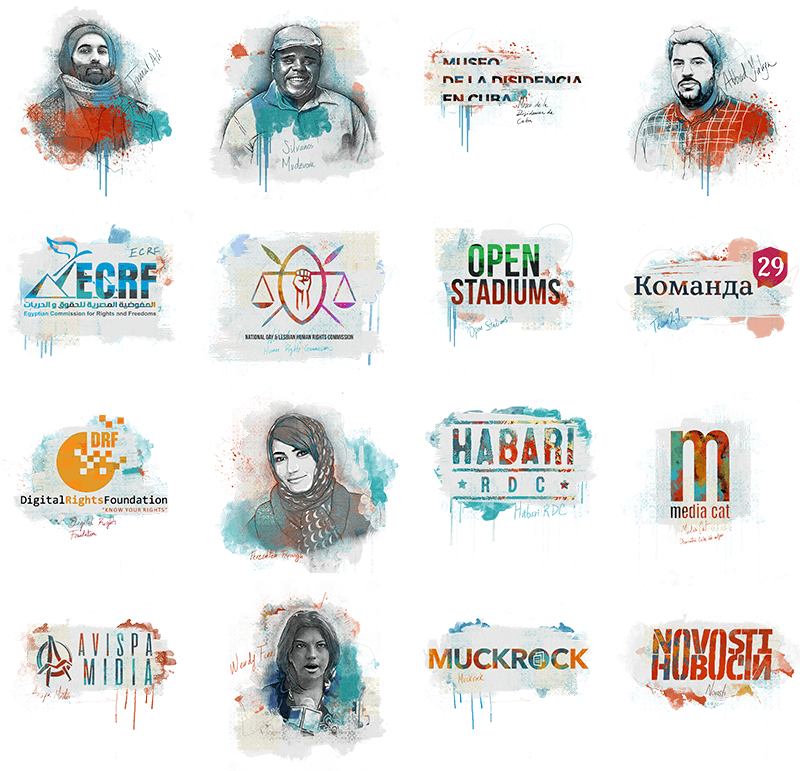

An exiled Azerbaijani rapper who uses his music to challenge his country’s dynastic leadership, a collective of Russian lawyers who seek to uphold the rule of law, an Afghan seeking to economically empower women through computer coding and a Honduran journalist who goes undercover to expose her country’s endemic corruption are among the courageous individuals and organisations shortlisted for the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowships.

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“Free speech is vital in creating a tolerant society. These nominees show us that even a small act can have a major impact. These groups and individuals have faced the harshest penalties for standing up for their beliefs. It’s an honour to recognise them,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards fellowships are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include rapper Jamal Ali who challenged the authoritarian Azerbaijan government in his music – and whose family was targeted as a result; Team 29, an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia; Fereshteh Forough, founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan; Wendy Funes, an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country.

Other nominees include The Museum of Dissidence, a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba; the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, a group proactively challenging LGBTI discrimination through the Kenya’s courts; Mèdia.cat, a Catalan website highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories; Novosti, a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia that deals with a whole range of topics.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 18th year, are BBC reporter Razia Iqbal, CEO of the Serpentine Galleries Yana Peel, founder of Raspberry Pi CEO Eben Upton and Tim Moloney QC, deputy head of Doughty Street Chambers.

Iqbal says: “In my lifetime, there has never been a more critical time to fight for freedom of expression. Whether it is in countries where people are imprisoned or worse, killed, for saying things the state or others, don’t want to hear, it continues to be fought for and demanded. It is a privilege to be associated with the Index on Censorship judging panel.”

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given year-long support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“This award feels like a lifeline. Most of our challenges remain the same, but this recognition and the fellowship has renewed and strengthened our resolve to continue reporting, especially on the bleakest of days. Most importantly, we no longer feel so alone,” 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards Journalism Fellow Zaheena Rasheed said.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Private Internet Access, Edwardian Hotels, Vodafone, media partner VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers and Psiphon. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected].

More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2018.

Jamal Ali

Azerbaijan

Jamal Ali is an exiled rapper and rock musician with a history of challenging Azerbaijan’s authoritarian regime. Ali was one of many who took to the streets in 2012 to protest spending around the country’s hosting of the Eurovision song contest. Detained and tortured for his role in the protests, he went into exile after his life was threatened. Ali has persisted in releasing music critical of the country’s dynastic leadership. Following the release of one song, Ali’s mother was arrested in a senseless display of aggression. In provoking such a harsh response with a single action, Ali has highlighted the repressive nature of the regime and its ruthless desire to silence all dissent.

Silvanos Mudzvova

Zimbabwe

Playwright and activist Silvanos Mudzvova uses performance to protest against the repressive regime of recently toppled President Robert Mugabe and to agitate for greater democracy and rights for his country’s LGBT community. Mudzvova specialises in performing so-called “hit-and-run” actions in public places to grab the attention of politicians and defy censorship laws, which forbid public performances without police clearance. His activism has seen him be traumatically abducted: taken at gunpoint from his home he was viciously tortured with electric shocks. Nonetheless, Mudzvova has resolved to finish what he’s started and has been vociferous about the recent political change in Zimbabwe.

The Museum of Dissidence

Cuba

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

Abbad Yahya

Palestine

Abbad Yahya is a Palestinian author whose fourth novel, Crime in Ramallah, was banned by the Palestinian Authority in 2017. The book tackles taboo issues such as homosexuality, fanaticism and religious extremism. It provoked a rapid official response and all copies of the book were seized. The public prosecutor issued a summons for questioning against Yahya while the distributor of the novel was arrested and interrogated. Yahya also received threats on social media and copies of the book were burned. Despite this, he has spent the last year giving interviews to international and Arab press and raising awareness of freedom of expression and the lives of young people in the West Bank and Gaza, particularly in relation to their sexuality.

Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms

Egypt

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms or ECRF is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.

National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission

Kenya

The National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission is the only organisation in Kenya proactively challenging and preventing LGBTI discrimination through the country’s courts. Even though being homosexual isn’t illegal in Kenya, homosexual acts are. Homophobia is commonplace and men who have sex with men can be punished by up to 14 years in prison, and while no specific laws relate to women, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga has said lesbians should also be imprisoned. NGLHRC has had an impact by successfully lobbying MPs to scrap a proposed anti-homosexuality bill and winning agreement from the Kenya Medical Association to stop forced anal examination of clients “even in the guise of discovering crimes.”

Open Stadiums

Iran

The women behind Open Stadiums risk their lives to assert a woman’s right to attend public sporting events in Iran. The campaign that challenges the country’s political and religious regime, and engages women in an issue many human rights activists have previously thought unimportant. Iranian women face many restrictions on using public space. Open Stadiums has generated broad support for their cause in and out of the country. As a result, MPs and people in power are beginning to talk about women’s rights to attend sporting events in a way that would have been taboo before.

Team 29

Russia

Team 29 is an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia. It is crucial work in a climate where hundreds of civil society organisations have been forced to close and where increasingly tight restrictions have been placed on public protest and political dissent since mass demonstrations rocked Russia in 2012. Team 29 conducts about 50 court cases annually, many involving accusations of high treason. Aside from litigation, they offer legal guides for activists, advice on what to do when state security comes for you and how to conduct yourself under interrogation.

Digital Rights Foundation

Pakistan

In late 2016, the Digital Rights Foundation established a cyber-harassment helpline that supported more than a thousand women in its first year of operation alone. Women make up only about a quarter of the online population in Pakistan but routinely face intense bullying including the use of revenge porn, blackmail, and other kinds of harassment. Often afraid to report how badly they are treated, women react by withdrawing from online spaces. To counter this, DRF’s Cyber Harassment Helpline team includes a qualified psychologist, digital security expert, and trained lawyer, all of whom provide specialised assistance.

Fereshteh Forough

Afghanistan

Fereshteh Forough is the founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan. Founded in 2015, this innovative project helps women and girls learn computer programming with the aim of tapping into commercial opportunities online and fostering economic independence in a country that remains a highly patriarchal and conservative society. Forough believes that with programming skills, an internet connection and using bitcoin for currency, Afghan women can not only create wealth but challenge gender roles and gain independence.

Habari RDC

Congo

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.

Mèdia.cat

Spain

Mèdia.cat is a Catalan website devoted to highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories. Unique in Spain, it was a particularly significant player in 2017 when the heightened atmosphere in Catalonia over the disputed independence referendum brought issues of censorship and the impartiality of news under the spotlight. The website provides an online platform that catalogues systematically, publicly and in real time censorship perpetrated in the region. Its map on censorship offers a way for journalists to report on abuses they have personally suffered.

Avispa Midia

Mexico

Avispa Midia is an independent online magazine that prides itself on its daring use of multimedia techniques to bring alive the political, economic and social worlds of Mexico and Latin America. It specialises in investigations into organised criminal gangs and the paramilitaries behind mining mega-projects, hydroelectric dams and the wind and oil industry. Many of Avispa’s reports in the last 12 months have been focused on Mexico and Central America, where the media group has helped indigenous and marginalised communities report on their own stories by helping them learn to do audio and video editing. In the future, Avispa wants to create a multimedia journalism school to help indigenous and young people inform the world what is happening in their region, and break the stranglehold of the state and large corporations on the media.

Wendy Funes

Honduras

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.

MuckRock

United States

MuckRock is a non-profit news site used by journalists, activists and members of the public to request and share US government documents in pursuit of more transparency. MuckRock has shed light on government surveillance, censorship and police militarisation among other issues. MuckRock produces its own reporting, and helps others learn more about requesting information. Last year the site produced a Freedom of Information Act 4 Kidz lesson plan to help educators to start discussions about government transparency. Since then, they have expanded their reach to Canada. The organisation hopes to continue increasing their impact by putting transparency tools in the hands of journalists, researchers and ordinary citizens.

Novosti

Croatia

Novosti is a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia. Although fully funded as a Serb minority publication by the Serbian National Council, it deals with a whole range of topics, not only those directly related to the minority status of Croatian Serbs. In the past year, the outlet’s journalists have faced attacks and death threats mainly from the ultra-conservative far-right. For its reporting, the staff of Novosti have been met with protest under the windows of the magazine’s offices shouting fascist slogans and anti-Serbian insults, and told they would end up killed like Charlie Hebdo journalists. Despite the pressure, the weekly persists in writing the truth and defending freedom of expression.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Jan. 25, 2018 (London and Columbia, Mo.) – Index on Censorship and the Missouri School of Journalism’s Global Journalist have formed a new partnership to help tell the stories of journalists exiled from their home countries for reporting the news.

Under the agreement, the U.K.-based freedom of expression group will publish interviews and articles about journalists in exile written by student journalists and professional staff at ‘Global Journalist’ on the Index on Censorship website.

The partnership is an extension of Global Journalist’s “Project Exile” series, which has published 52 interviews with exiled journalists from 31 different countries since September 2014. The series has included interviews with former New York Times’ Iran correspondent Nazila Fathi, Iraqi BBC News cameraman Qais Najim and Newsweek Japan cartoonist Wang Liming of China, also known as “Rebel Pepper,” who is the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Arts Fellow.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 262 journalists were in jail for their work in 2017. Though estimates vary, many others escape prison or violence by fleeing their home countries each year.

“Telling the stories of journalists who lose their right to live in their own country for simply doing their job is one way to highlight efforts to roll back freedom of expression around the globe,” said Fritz Cropp, the associate dean for global programs at the Missouri School of Journalism. “Together with Index on Censorship we hope this effort will intensify scrutiny of governments that seek to intimidate the press into submission.”

Index on Censorship is a London-based nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. It publishes work by censored writers and artists, promotes debate, and monitors threats to free speech through its Mapping Media Freedom project. Founded in 1972, Index on Censorship magazine publishes original creative writing and articles about free expression from across the globe. Its contributors have included noted authors and journalists including Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa and Václav Havel.

Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516816724036-b6713aa4-3a80-10″ taxonomies=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Serious threats verified by the platform in January indicate that pressure has not let up in 2018. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

A Serbian minister announced on 12 January that he is suing the Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), nominees for the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, over the publications reporting on offshore companies and assets outlined in the Paradise Papers, a set of 13.4 million confidential documents relating to offshore investments leaked in November 2017.

Nenad Popovic, a minister without portfolio, was the main Serbian official mentioned in the leaked documents that exposed the secret assets of politicians and celebrities around the world. Popovic was shown to have offshore assets and companies worth $100 million.

“Serbian and Cypriot authorities have already launched lawsuits against various media workers so we’re particularly concerned that investigative outlets like KRIK are being sued for uncovering corruption of government officials,” Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom said. “Journalists reporting on corruption were repeatedly harassed, and in some cases murdered, in 2017, so going into the new year, we need to ensure that their safety is prioritised in order to preserve vital investigative reporting.”

KRIK was one of the 96 media organisations from over 60 countries that analysed the papers.

In December 2017 suspended senior state attorney Eleni Loizidou sued the daily newspaper Politis, seeking damages of between €500,000-2 million on the grounds that the media outlet breached her right to privacy and personal data protection. The newspaper had published a number of emails Loizidous had sent from her personal email account that implied Loizidou may have assisted the Russian government in the extradition cases of Russian nationals.

On 10 January the District Court of Nicosia approved a ban which forbids Politis from publishing emails from Loizidou’s account which she claims have been intercepted.

The ban will be in effect until the lawsuit against the paper is heard or another court order overrules it.

On 4 January, the Iranian embassy in London asked the United Kingdom Office of Communications to censor Persian language media based in the UK. The letter said the media’s coverage of the protests had been inciting people to “armed revolt”.

The letter primarily focused on BBC Persian and Manoto. BBC Persian has previously been criticised by Iranian intellectuals and activists for not distancing itself sufficiently from the Iranian government.

A journalist who works for the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) was branded a threat to national security on 4 January and ordered to leave the country within 24 hours after being detained.

Olga Kurlaeva went to Latvia planning to make a film about former Latvian president Vaira Vike-Freiberga. Kurlaeva had interviewed activists critical of Latvia’s policies towards ethnic Russians and was planning on interviewing other politicians critical of Latvian policies.

Two days earlier, her husband, Anatoly Kurlajev, a producer for Russian TV channel TVC, was detained by Latvian police and reportedly later deported to Russia.

Elchin Mammad, the editor-in-chief of the online news platform Yukselis Namine, wrote in a public Facebook post on 4 January that he is being investigated for threatening and beating a newspaper employee.

Mammad wrote that the alleged victim, Aygun Amiraslanova, was never employed by Yukselis Namine and potentially does not exist. Mammad believes this is another attempt to silence his newspaper and staff.

Mammad was previously questioned by Sumgayit police in November about his work at the newspaper. The police told him that he was preventing the development of the country and national economic growth. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516702060574-c4ac0556-7cf7-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published 52 interviews with exiled journalists from 31 different countries.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”97517″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]It was a story that shook Argentine politics. For the journalist who broke the news, it upended his life.

On January 18, 2015, Argentine prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found dead of a gunshot wound in his apartment just days after releasing a 289-page report accusing then president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and her foreign minister of covering up Iran’s involvement in the 1994 bombing of Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA), a Jewish community center. The explosion killed 85 people and was the deadliest terrorist attack in the country’s history.

The journalist who broke the story of Nisman’s death on Twitter was Damian Pachter, a young Argentine-Israeli reporter for the English-language Buenos Aires Herald.

“Prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found in the bathroom of his house at Puerto Madero. He was not breathing. The doctors are there,” Pachter wrote.

That tweet set off a chain of events that led both to an investigation of Kirchner and to Pachter fleeing Argentina for Israel.

Kirchner’s government, which had been seeking to undermine Nisman’s allegations, immediately labeled his death a suicide, as Nisman’s body had been discovered with a handgun nearby. “What led a person to make the terrible decision to take his own life?” she wrote on Facebook, soon afterwards.

Nisman’s death and Kirchner’s move to call it a suicide triggered a massive protest in Buenos Aires. The Argentine government was later forced back away from its claims that Nisman had committed suicide, and Kirchner’s Front for Victory narrowly lost presidential elections later that year. An investigation into Nisman’s death concluded earlier this year that it was a homicide.

Pachter, who had been working on a freelance story for an Israeli newspaper about Nisman’s investigation of the bombing and the government’s efforts cover up Iran’s role, was soon targeted by the government.

Six days after Nisman’s body was found, he fled to Israel with nothing but a backpack.

Pachter, 33, now works as a producer for Israel’s i24 News and as a host for Ñews24 in Tel Aviv. As for Kirchner, she has consistently denied any role in Nisman’s death or covering up Iran’s role in the AMIA bombing. In October, she won election to the Argentine senate, a position that gives her legal immunity from prosecutor’s efforts to charge her with treason and covering up the government’s role in Nisman’s death.

Pachter spoke with Global Journalist’s Maria F. Callejon about the strange days after Nisman’s death and his flight from Argentina. Below, an edited version of their conversation, translated from Spanish:

Global Journalist: Tell us about the night of Nisman’s death.

Pachter: I was in the living room when I received the news of Nisman’s death from a source at approximately 11 p.m. For 35 minutes I talked to my source to try to verify it. At 11:35 p.m. I sent the first tweet: “I have been informed of an incident at Prosecutor Nisman’s house.”

I already knew what had happened, but I took the time to talk to my source, to check there were no mistakes and to get as much detail as I could. At 12:08 a.m. I tweeted: “Prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found in his bathroom at his house in Puerto Madero. He wasn’t breathing. The doctors are there.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”97522″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://twitter.com/damianpachter/status/557011746855321600″][vc_column_text]GJ: What were your first thoughts after receiving the information?

Pachter: I was very robotic. Immediately, I started fact-checking. Pretty much like a machine: at first, it was shocking, but I was the one who got it and I had to make sure that everything was true to then publish it. That was it. I thought I was going to be fired for tweeting first. But I told myself that if I was going to be fired for something, it might as well be this, but I had to publish it.

GJ: Did you think the government would try to cover up the incident?

Pachter: I can’t say that I didn’t, but I didn’t imagine anything precise. Knowing the government and how they treated journalists critical of them, I thought that they would create a media campaign against me. I had delivered news that affected their power, I had to have the [courage] to endure what came after. It’s part of the job. I got into journalism for this kind of thing. There are ups and downs, but you have to do your job and that is to publish what they want to hide. The investigation of Nisman’s death took two years and a new government. The previous government almost shut it down. A couple months ago, the police determined it was a homicide. Think about what would’ve happened if nobody had said anything.

GJ: What happened the day after you reported this?

Pachter: We were all in shock, nobody could believe what was happening. There was an atmosphere of fear. I interpreted that as the government making a show of their power. They had ordered the killing of the prosecutor that had accused them, and I think they didn’t consider the consequences. They didn’t think that this would be important nor that it would have the popular response it had.

GJ: How was the rest of the week?

Pachter: People were calling me, I swear, they wouldn’t stop calling from all over the world. We started doing some appearances on some big networks like CNN. In the meantime, I tried to do my job as normally as I could, but the emotion was so overwhelming, that didn’t work. I had too much adrenaline. In the days afterwards, a source of mine started messaging me to come visit. That source lived out of the city, so I didn’t pay too much attention. In the meantime, I was preparing to face further attacks from the government. I knew I was going to be targeted for being Israeli and Jewish. So I thought I would go on TV and set the record straight. I knew that they would attack me for that. I was used to the government. Any journalists that confronted them would suffer the consequences.

GJ: Were you attacked for being Jewish?

Pachter: They will do anything to discredit you. Instead of saying that I was a journalist doing my job, they said that I was working for the Israeli intelligence services, that I was an undercover agent. The government took pictures from my Facebook account of me in the Israeli army, something that I’d already talked about publicly. They marked my face with a yellow circle and sent it to pro-government groups. While this was happening, my source kept insisting that I visit. On Thursday [five days after Nisman’s body was discovered], I got an email from a colleague. The link in the mail showed that Télam, Argentina’s government news agency, had published some information about me. My name was misspelled, my workplace was incorrect and they had changed my tweets [about Nisman’s death]. This disturbed me and I thought something was going on. I sent that information to my source, who again said I should come visit. That’s when it hit me, after four days. My source was saying too that something was going on.

GJ: What did you do then?

Pachter: I left the newsroom and left my car parked there. I took a taxi back to my apartment. There, I packed a backpack with clothes for three days. That was my plan, to go and hide for three days until it all calmed down. For whatever reason, I grabbed my Israeli passport and my identity card. Then I took a bus out of town to meet with my source. While I was waiting at the cafe of a gas station, I realized a man had come into the cafe and there was something strange about him, his body language and his presence. I sat still in my seat. Time passed and this man was still there, not asking for anything to drink or eat. My source called me and told me to stay wait for him. Twenty minutes later, he was there. He came in through the back door, so he saw the man sitting behind me. My source approached me and said: “Don’t turn around. You have an intelligence officer behind you. Look at my camera and smile.” We pretended as if he were taking my picture, but he really took one of the man. When he realized what we were doing, he left. Right then I knew I had nothing else to do in the country. I was leaving. I was sure they were going to kill me, taking into account what happened to Nisman.

GJ: How did you plan your trip?

Pachter: At the cafe I did what I could to book a flight as soon as possible. The soonest one was with Argentina Airlines, from Buenos Aires to Montevideo to Madrid to Tel Aviv. I went straight to the airport to catch my flight on Saturday [six days after Nisman’s body was found]. I met my mom and said goodbye. I told her what was happening and she understood what was at stake. I also met with two colleagues of mine who were there to document it all. And then I left. During my flight, the Pink House [Argentina’s presidential residence and office] published on its official Twitter account the details of my flight. There it was clearly, just what I had thought: this was official persecution.

El periodista Damián Pachter viajó a Uruguay con pasaje de regreso para el 2 de febrero http://t.co/dUGwifa9AO pic.twitter.com/muWhkHEvfK — 🇦🇷 (@CasaArgentinaAR) January 25, 2015

GJ: How did you feel when you got to Israel?

Pachter: Some friends and journalists from international media and local media met me there. Once I was there, it felt like a weight off my back. Once we landed, I felt safe.

GJ: Since you went into exile, Kirchner’s government lost the election and she was replaced by opposition candidate Mauricio Macri. Have you considered going back?

Pachter: For now, I don’t want to go back, as much as people tell me everything is fine. I have many feelings that discourage me from going. I was expelled, in a way, from Argentina. I was forced to go into exile because of my job.

GJ: Was it worth it?

Pachter: Yes, of course. I would do it a thousand times.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]